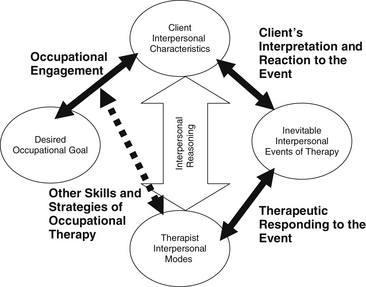

Chapter 4 An Introduction to Therapeutic use of Self in Occupational Therapy The Intentional Relationship Model in Occupational Therapy Applying the Intentional Relationship Model in Group Therapy Situations Adaptive Versus Maladaptive Group Dynamics Managing Maladaptive Dynamics of Systems Applying IRM to Co-Leadership Situations 1 Define therapeutic use of self in occupational therapy. 2 Understand how the intentional relationship model may guide use of self in occupational therapy. 3 Understand the application of the intentional relationship model in group therapy approaches. 4 Define the interpersonal skills necessary for successful group therapy outcomes. 5 Understand the difference between activity focusing and interpersonal focusing according to the intentional relationship model. 6 Understand the role of group dynamics (adaptive and maladaptive) in therapy outcomes. 7 Apply the intentional relationship model to a group therapy case example. Occupational therapy (OT) lays claim to an ample literature base supporting a holistic understanding that includes the psychosocial and interpersonal characteristics of a client, in addition to his or her actual physical, sensory, or cognitive impairments.32 In individual and group therapy applications, terms such as client-centered care, empathy, and narrative are referenced as talismans reflecting this emphasis. In recent history, there have been three central movements with which the client-therapist relationship has been associated: Collaborative and client-centered approaches emphasize the readjustment of power within the therapeutic relationship and support client control over decision-making and problem-solving.17,34 Generally, these approaches emphasize open communication, orientation toward the client’s perspective, recognition of the client’s strengths, shared goals and priorities, and a collaborative partnership. Group therapy leaders that emphasize collaboration derive wisdom from group and encourage mutual sharing and exchange during the process. Within this perspective, there has also been an emphasis on therapist self-awareness. Therapists are encouraged to recognize and control negative reactions toward difficult clients, incorporate their own life experiences into an understanding of their clients’ perspectives, and draw on their personal reactions to clients to guide their clinical reasoning. In conjunction with collaborative and client-centered approaches, the contemporary era has also been characterized by an emphasis on empathy and caring within the therapeutic relationship. This can be summarized as an emphasis on the emotional exchange that occurs between client and therapist, on goal-directed activity, and on activities that promote personal growth).3,4,6,8,12,18,19–22,24,25,35 Empathy has been written about extensively within the OT literature. Peloquin19–21,23 emphasized the roles of art, literature, imagination, and self-reflection. She further argued that the fundamental characteristics required to develop one’s therapeutic use of self are well conveyed through reading literature and viewing and doing art 18, 19. She believed that providing therapists with both fictional and nonfictional poems and stories that illustrate empathy and the depersonalizing consequences of neglectful attitudes and failed communication could be a powerful motivator for the development of caring.20–22 Clinical reasoning and narrative approaches compose the final general category of contemporary scholarship that includes the client-therapist relationship as a focal point.9,10,13–16,27–31 These approaches emphasize the role of the therapist in understanding and reflecting about the unique way in which clients think about and summarize key events in their lives.11 Clinical reasoning approaches incorporate thinking about the relationship as a component of one’s overall approach to making sense of assessment findings and developing a treatment plan.16 This element has been referred to as interactive reasoning16 and it has been described as an “underground practice” in OT7 because relatively little is known about the mechanisms that underlie it. Narrative approaches (e.g., narrative reasoning) were developed in tandem with clinical reasoning approaches.10,15 Narrative approaches seek to organize and make sense of information from clients by encouraging them to present information about themselves through storytelling, poetry, or metaphor. Thinking in story form is thought to allow both the client and the therapist to discover the meaning of the impairment experience according to the client’s unique perspective. Therapeutic approaches are then focused toward reconstructing more hopeful narratives to reshape one’s life story. These concepts and values have been upheld in academic research as well as in clinical settings. For example, a growing number of studies indicate that the client-therapist relationship is a key determinant of whether OT has been successful.1,3,5 However, there has been a lack of cohesiveness between evidence and discussion about the importance of these values and literature describing the concrete skills and competencies that are necessary to enact them within a clinical setting. According to the American Occupational Therapy Association’s 2008 Practice Framework 1, therapeutic use of self is the “therapist’s planned use of his or her personality, insights, perceptions, and judgment as part of the therapeutic process”26 (p. 626). Although some believe that use of self is intuitive, a recent survey study found that most practicing occupational therapists within the United States agree that the field lacks sufficient knowledge about therapeutic use of self.33 For example, only 4.3% of respondents reported taking a class that focused only and specifically on this topic in OT school.33 In this chapter, we provide a rationale for the introduction of a new conceptual model of use of self, describe the model, and describe its application in group therapy. A case example is presented that illustrates a clinician’s use of this model in a group therapy situation. Contemporary OT practice requires a therapist to understand how to manage the relationship with a client to optimize occupational engagement.32 A conceptual practice model that provides a set of concrete tools and suggestions for development of interpersonal skills is a necessary guide in assisting occupational therapists in developing an understanding of use of self. The intentional relationship model (IRM) explains therapeutic use of self and its relationship with occupational engagement. It defines the most critical components of the client-therapist relationship as they are enacted in practice. According to IRM, “The client is the focal point. It is the therapist’s responsibility to work to develop a positive relationship with the client and to respond appropriately”32 (p. 48). The IRM focuses on four main components of the therapist-client relationship. These are (1) the client, (2) the interpersonal events that occur during therapy, (3) the therapist, and (4) the occupation. The IRM asks therapists to observe and understand their clients from an interpersonal perspective, to be prepared to respond therapeutically to rifts and other significant interpersonal events that occur during therapy, and to communicate within a mode that matches the client’s interpersonal needs of the moment.32 This model, which is illustrated in Figure 4-1, provides a theoretical framework for understanding the significance that all interactions have and guidance in how to therapeutically respond in a manner that best serves the client. Each of the central components of the model is described in the following pages, and more extensive information is presented in Taylor.32 At first appraisal, the relevant aspects that the client brings into a therapeutic relationship may appear to be obvious. For example, a client’s heightened need for control becomes salient the moment he or she asks what seems to be an unnecessary question for the third time. A client’s reluctance to engage in an activity may become apparent when he or she appears not to have heard a given instruction. One quickly learns of a client’s limited capacity to assert his or her needs when the client is found lying on a mat without a means to right himself or herself, not having asked anyone for help. Although these are common characteristics of clients in everyday practice, they are not traditionally discussed as fundamental aspects of OT care plans or documented in a client’s chart notes. Understanding the more challenging aspects of a client’s interpersonal characteristics from an objective but empathic perspective assists a therapist to act in a way that is intentional and facilitating of occupational engagement (Figure 4-2). IRM defines the essential interpersonal characteristics of a client in terms of 12 categories, presented in Table 4-1. TABLE 4-1 Client Interpersonal Characteristics In summary, understanding client interpersonal characteristics is fundamental to planning how to respond during therapeutic interactions. Familiarizing oneself with the interpersonal characteristics of each of one’s clients becomes particularly important in group therapy situations, in which it is important to consider the effects of one client’s behavior on another, in addition to the effects of the therapist’s behavior on each and every one of the clients and on the group as a whole. An extensive discussion of client characteristics may be found in Taylor.32 Similar to client characteristics, difficult or emotional circumstances that occur during therapy are a normal part of everyday practice for the experienced therapist. However, knowing how to anticipate and respond to them in a deliberate and planned therapeutic way is not necessarily an assumed, universal skill. According to IRM,32 an interpersonal event is a naturally occurring communication, reaction, process, task, or general circumstance that occurs during therapy and that has the potential to detract from or strengthen the therapeutic relationship. In therapy, these events may be precipitated by the following kinds of circumstances: These are only a few of the myriad possible interpersonal events that occur during the course of OT. A more extensive list is presented in Table 4-2 and in Taylor.32 When interpersonal events occur, their interpretation by the client is a product of the client’s unique set of interpersonal characteristics. Sometimes the event may have a significant effect on the client and other times a client will be unaffected or minimally affected. When such events occur, it is important that the therapist be aware that the event has occurred and take responsibility for responding appropriately. TABLE 4-2 The Inevitable Interpersonal Events of Occupational Therapy Interpersonal events are part of the constant give and take that occurs in a therapy process. They are distinguished from other events or processes in that they are charged with the potential for an emotional response either when they occur or later after reflection. Consequently, if they are ignored or responded to less than optimally, these events can threaten both the therapeutic relationship and the client’s occupational engagement. When optimally responded to, these events can provide opportunities for positive client learning or change and for solidifying the therapeutic relationship. Because they are unavoidable in any therapeutic interaction, one of the primary tasks of a therapist practicing according to the IRM is to respond to these inevitable events in a way that leads to repair and strengthening of the therapeutic relationship.32

Therapeutic Use of Self

Applying the Intentional Relationship Model in Group Therapy

An Introduction to Therapeutic use of Self in Occupational Therapy

The Intentional Relationship Model in Occupational Therapy

Client Interpersonal Characteristics

Interpersonal Characteristic

Group Therapy Example

Communication style

Elizabeth’s group communication style appears to be a reluctance caused by a lack of confidence when asked her opinion on what activities the group should work on in a session. In one-on-one environments she is quick to provide her opinion.

Capacity for trust

During a session in which the therapist incorporated an overhead swing, all of the girls demonstrated hesitancy in attempting the activity despite encouragement. Alex has had multiple interactions both one on one and in the group with the therapist and displayed increased trust for this activity. Observing Alex enjoy the task encouraged the two other girls to engage in it.

Need for control

Iris’ high need for control is evident during a parallel play activity of coloring because she frequently chooses and distributes crayon colors for the other girls to use, hoarding the most popular colors for herself.

Capacity to assert needs

In the coloring scenario, Elizabeth is unable to ask for a crayon color to be returned that has been taken from her despite her desire for it. Despite the therapist offering support for Iris to return the crayon, Elizabeth instead quickly picks up a crayon offered to her as a replacement by Iris.

Response to change and challenge

Unable to locate a commonly used CD for music during the group, Alex is quick to look for alternatives; however, Iris appears distraught by this inconsistency and withdraws from the group activity.

Affect

Because of Iris’ high need to control the group and her dynamic affect, the therapist is careful to be sensitive to how her emotional vacillations effect the entire group and minimizes how these behaviors could be used by Iris as a tool for control.

Predisposition to giving feedback

During decision making for activity choice, Elizabeth infrequently provides input. When encouraged to provide a very basic choice, she displays prolonged hesitation; ultimately, she is dominated by others in the group and is unable to verbalize her opinion. Later, when alone with the therapist she acknowledges that she knew what she wanted to choose but was afraid the other girls would not like it.

Capacity to receive feedback

When Iris is encouraged to be more sensitive to turn taking when making choices, she is unable to receive this feedback without obvious disengagement and irritability for a brief time in response to the therapist.

Response to human diversity

In this particular playgroup, the girls all have historical difficulties with a male in their immediate family dynamic. Because of this, when attempts have been made for a male therapist to lead the group, each girl displays increased withdrawal behaviors and disengagement from activity.

Orientation toward relating

Each of the girls displays varying levels of relating to one another. Alex and Elizabeth have a nurturing and mutually helping relationship (e.g., they frequently hold hands together while walking); however, Iris has the need to remain safely distant with limited displays of intimacy to the other girls.

Preference for touch

Each child in the playgroup has different preferences for touch, most notable during times of distress. Iris prefers limited physical touch, withdrawing when it is attempted, whereas Alex prefers prolonged hugs to comfort her.

Capacity for reciprocity

During one session, the therapist gets a paper cut. Differences are noted with each child in her reciprocity toward the therapist’s pain. Elizabeth is quick to ask her if the therapist is okay; Alex appears distressed by this occurrence, with decreased eye contact and verbalizations; and Iris begins telling a story about how many times she has had paper cuts and the effect they had on her.

The Inevitable Interpersonal Events of Therapy

Client resistance (e.g., a client refuses, either actively or passively, to communicate or participate in some activity)

Client resistance (e.g., a client refuses, either actively or passively, to communicate or participate in some activity)

Therapist behavior (e.g., the therapist provides feedback that a client finds difficult to hear)

Therapist behavior (e.g., the therapist provides feedback that a client finds difficult to hear)

Client display of strong emotions in therapy (e.g., a client becomes tearful when reflecting on the extent of his or her impairment before beginning therapy, as compared with the progress made recently)

Client display of strong emotions in therapy (e.g., a client becomes tearful when reflecting on the extent of his or her impairment before beginning therapy, as compared with the progress made recently)

A difficult circumstance of therapy (e.g., a client is uncomfortable practicing toileting hygiene with the therapist)

A difficult circumstance of therapy (e.g., a client is uncomfortable practicing toileting hygiene with the therapist)

A rift or conflict between the client and therapist (e.g., a client disagrees with a treatment recommendation and confronts the therapist in a way that the therapist perceives is personal)

A rift or conflict between the client and therapist (e.g., a client disagrees with a treatment recommendation and confronts the therapist in a way that the therapist perceives is personal)

Differences concerning the aim of therapy (e.g., a client insists on a goal that the therapist believes is not attainable, or the therapist recommends a goal that the client rejects)

Differences concerning the aim of therapy (e.g., a client insists on a goal that the therapist believes is not attainable, or the therapist recommends a goal that the client rejects)

Client requests that test the boundaries or limits of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., the client invites the therapist to attend his or her wedding)

Client requests that test the boundaries or limits of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., the client invites the therapist to attend his or her wedding)

Interpersonal Event

Definition

Group Therapy Example

Expression of strong emotion

External displays of internal feelings are shown with a high level of intensity beyond usual cultural norms for interaction. Can be positive or negative expressions.

During the end of playgroup and immediately following a power dilemma that was resolved with successful use of Empathizing Mode, Iris gives a hug to the therapist and exclaims she loves the therapist more than anybody else in the world.

Intimate self-disclosures

Statements or stories reveal something unobservable, private, or sensitive about the person making a disclosure. These can be stories about oneself or about close others.

Alex discloses during imagination time and story development that her mother and father are getting divorced. While casually brought up during the group conversation, this disclosure reveals an area of stress for Alex.

Power dilemmas

Tensions arise in the therapeutic relationship because of clients’ innate feelings about issues of power, the inherent situation of therapy, the therapist’s behavior, or other circumstances that underscore clients’ lack or loss of power over aspects of their lives.

During clean up time at the conclusion of playgroup, Iris’ refusal to put her toys away is coupled with her sitting in the middle of the floor with her arms folded. It is important that the therapist does not attempt to force her to participate here, because a power dilemma is a common end result.

Nonverbal cues

Communications do not involve the use of formal language. Some examples of these are facial expressions, movement patterns, body posture, and eye contact.

Elizabeth has a tendency to limit eye contact and engage in idle fiddling with a toy during discussion of client choices for activities at the beginning of playtime.

Crisis points

Unanticipated, stressful events cause clients to become distracted or temporarily interfere with clients’ ability for occupational engagement.

During an outing to a playground, Alex becomes frightened by a passing dog, causing tearfulness and requiring the therapist to decrease attention to the group as a whole to console Alex. Careful attention had to be given to return to the group’s needs as soon as Alex was consoled to avoid escalation of the crisis to others in the group.

Resistance and reluctance

Resistance is a client’s passive or active refusal to participate in some or all aspects of therapy for reasons linked to the therapeutic relationship. Reluctance is disinclination toward some aspect of therapy for reasons outside the therapeutic relationship.

Elizabeth’s refusal to follow the other children in rolling somersaults in the grass is reluctance based on her long-standing sensory processing difficulties.

Boundary testing

A client behavior violates or asks the therapist to act in ways outside the defined therapeutic relationship.

When asked to participate in an activity, Iris states she will only participate if the therapist will take her to the candy store after therapy.

Empathic breaks

The therapist fails to notice or understand a communication from a client, or communication or behavior initiated by the therapist is perceived by the client as hurtful or insensitive.

During the group’s parallel play time Alex proudly displays her completed coloring project, which is below her age appropriateness. The therapist congratulates her but states that it must have been easy because it was from a baby’s coloring book. Alex immediately responds with a deflated affect.

Emotionally charged therapy tasks and situations

Activities or circumstances can lead clients to become overwhelmed or experience uncomfortable emotional reactions such as embarrassment, humiliation, or shame.

During a physically challenging activity, Elizabeth suffers from increased oral secretions that she is unable to perceive. Iris points this out to the other group members, which embarrasses Elizabeth and makes her withdraw from the activity.

Limitations of therapy

There are restrictions on the available or possible services, time, resources, or therapist actions.

During playtime decision making, a promise was made that, at the conclusion of the hour, the group would be allowed to play with a favorite toy. At the appropriate time for this reward to occur, the toy has been misplaced and is unable to be found for follow through of the promised reward.

Contextual inconsistencies

Any aspect of a client’s interpersonal or physical environment changes during the course of therapy.

This playgroup has three therapists who typically treat them; however, when a new therapist must assume the group session, the group requires some time to adjust to this new individual.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access