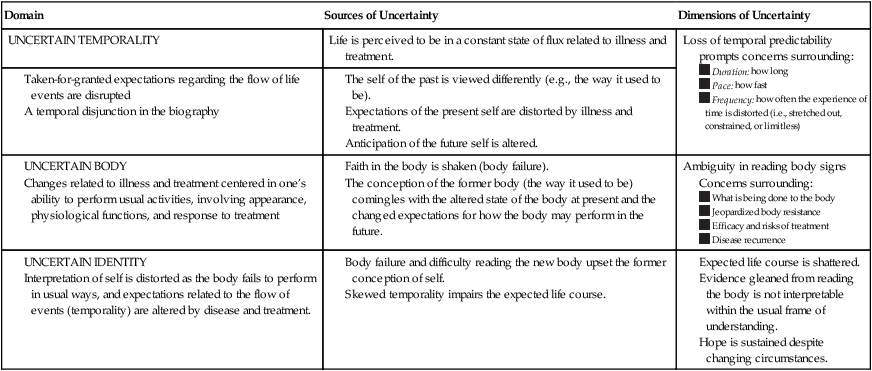

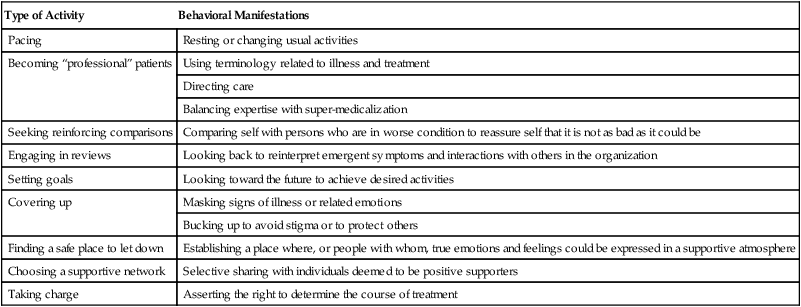

Janice Penrod, Lisa Kitko and Chin-Fang Liu Dissemination of research findings and methodological papers is a hallmark of Wiener’s work. She has produced a steady stream of research and theory articles since the mid-1970s. In addition, she has authored or coauthored several books (Strauss, Fagerhaugh, Suczek, & Wiener, 1997; Wiener, 1981, 2000; Wiener & Strauss, 1997; Wiener & Wysmans, 1990). In her early efforts, Wiener focused on illness trajectories, biographies, and the evolving medical technology scene. From the late 1980s to 1990s, Wiener focused on coping, uncertainty, and accountability in hospitals. Then she completed a study examining the quality management and redesign efforts in hospitals and the interplay between agencies and hospitals around the issue of accountability (Wiener, 2000). All of this work is grounded in her strong methodological expertise and sociological perspective. Dodd’s research was designed to test self-care interventions (PRO-SELF Program) to manage the side effects of cancer treatment (mucositis) and symptoms of cancer (fatigue, pain). This research entitled The PRO-SELF: Pain Control Program—An Effective Approach for Cancer Pain Management was published in Oncology Nursing Forum (West, Dodd, Paul, Schumacher, Tripathy et al., 2003). Currently, she teaches in the Oncology Nursing Specialty. In 2002, she instituted two new courses (“Biomarkers I and II”) developed by the Center for Symptom Management Faculty Group. Being ill creates a disruption in normal life. Such disruption affects all aspects of life, including physiological functioning, social interactions, and conceptions of self. Coping is the response to such disruption. Although coping with illness has been of interest to social scientists and nursing scholars for decades, Weiner and Dodd clearly explicate that formerly implicit theoretical assumptions have limited the utility of this body of work (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, 2000). Because the processes surrounding the disruption of illness are played out in the context of living, coping responses are inherently situated in sociological interactions with others and biographical processes of self. Coping is often described as a compendium of strategies used to manage the disruption, attempts to isolate specific responses to one event that is lived within the complexity of life context, or assigned value labels (e.g., good or bad) to the responsive behaviors that are described collectively as coping. Yet, the complex interplay of physiological disruption, interactions with others, and the construction of biographical conceptions of the self warrants a more sophisticated perspective of coping. The Theory of Illness Trajectory* addresses these theoretical pitfalls by framing this phenomenon within a sociological perspective of a trajectory that emphasizes the experience of disruption related to illness within the changing contexts of interactional and sociological processes that ultimately influence the person’s response to such disruption. This theoretical approach defines this theory’s significant contribution to nursing: coping is not a simple stimulus-response phenomenon that can be isolated from the complex context of life. Because life is centered in the living body, the physiological disruptions of illness permeate other life contexts to create a new way of being, a new sense of self. Responses to the disruptions caused by illness are interwoven into the various contexts encountered in one’s life and the interactions with other players in those life situations. Within this sociological framework, Wiener and Dodd address serious concerns regarding conceptual overattribution of the role of uncertainty in the framework of understanding responses to living with the disruptions of illness (Wiener & Dodd, 1993). An old adage tells us that nothing in life is certain, except death and taxes. Living is fraught with uncertainty, yet illness (especially chronic illness) compounds this uncertainty in profound ways. Being chronically ill exaggerates the uncertainties of living within being for those who are compromised (i.e., by illness) in their capability to respond to these uncertainties. Thus, although the concept of uncertainty provides a useful theoretical lens for understanding the illness trajectory, it cannot be theoretically positioned so as to overshadow conceptually the dynamic context of living with chronic illness. As the data for the larger study were analyzed, it became apparent to Dodd (principal investigator) that the qualitative interview data held significant insights that could further inform the study. Wiener, a grounded theorist who collaborated with Anselm Strauss, one of the method’s founders, was subsequently recruited to conduct a secondary analysis of interview data. It should be noted that traditional grounded theory methods typically involve a concurrent, reiterative process of data collection and analysis (Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1965). As theoretical insights are identified, sampling and the focus of subsequent data collection theoretically are driven to flesh out emergent concepts, dimensions, variations, and negative cases. However, in this project, the data were collected previously using a structured interview guide; this was a secondary analysis of an established data set. When considering the authors’ use of adapted grounded theory methods to analyze preexisting empirical evidence, several insights may be useful to support the integrity of this work. First, Wiener was certainly well prepared to advance new applications of the method by her training and experience as a grounded theorist. The methodological credibility of this researcher supports her extension of a traditional research method into a new application within her disciplinary perspective (sociology). Further, it is important to recall the size of this data set: 100 patients and families were interviewed 3 times each, for a total of 300 interviews. This is a very large data set for a qualitative inquiry. Oberst pointed out that given this volume of data, some semblance of theoretical sampling (within the full data set) would likely be permitted by the researchers (Oberst, 1993). But the sheer size of the data set does not tell the whole story. Sampling patients who had a relatively wide range of types of cancers (ranging from gynecological cancers to lung cancer) and both patients undergoing initial chemotherapeutic treatment and those receiving treatment for recurrence contributed significantly to variation in the data set. These sampling strategies ultimately contributed to establishing an appropriate sample, especially for revealing a trajectory perspective of change over time. Finally, despite the structured format of the interview, it is important to note that the patients and families dialogued about the previous month’s events in a form of “brainstorming” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 18). This technique would allow the subjects to introduce almost any topic that was of concern to them (regardless of the subsequent structure of the interview). The audiotaping and verbatim transcription of these dialogues contributed to the variation and appropriateness of the resultant data set. Given these insights, it may be concluded that the empirical evidence culled through the interviews conducted during the larger study provided adequate and appropriate data for a secondary analysis using expertly adapted grounded theory methods.

Theory of Illness Trajectory

CREDENTIALS OF THE THEORISTS

Carolyn L. Wiener

Marylin J. Dodd

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree