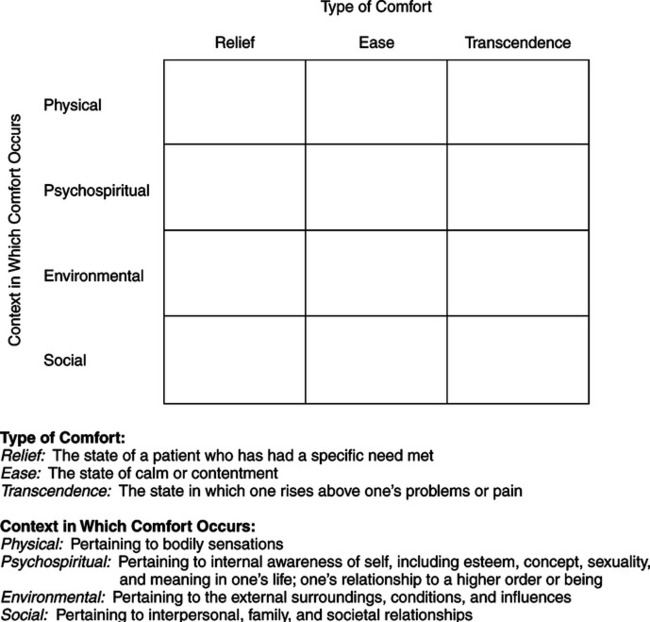

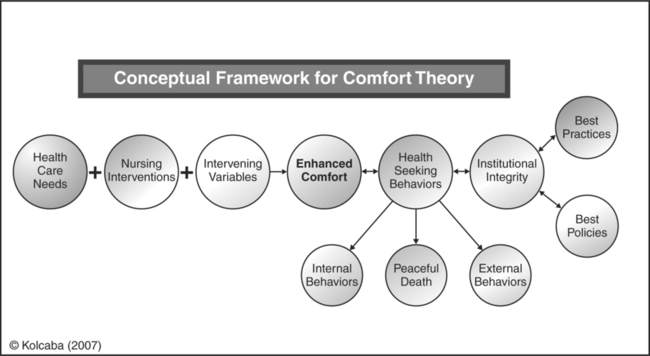

After graduating with her master’s degree in nursing, Kolcaba joined the faculty at The University of Akron College of Nursing. She acquired and maintains American Nurses Association (ANA) certification in gerontology. She returned to CWRU to pursue her doctorate in nursing on a part-time basis while continuing to teach. Over the next 10 years, she used course work in her doctoral program to develop and explicate her theory. She published a concept analysis of comfort with her philosopher-husband (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991), diagrammed aspects of comfort (Kolcaba, 1991), operationalized comfort as an outcome of care (Kolcaba, 1992a), contextualized comfort in a middle range theory (Kolcaba, 1994), and tested the theory in an intervention study (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999). Kolcaba began her theoretical work as she diagrammed her nursing practice early in her doctoral studies. When Kolcaba presented her framework for dementia care (Kolcaba, 1992b), a member of the audience asked, “Have you done a concept analysis of comfort?” Kolcaba replied that she had not but that would be her next step. That question began her long investigation into the concept of comfort. Historical accounts of comfort in nursing are numerous. For example, Nightingale (1859) exhorted, “It must never be lost sight of what observation is for. It is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous information or curious facts, but for the sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort” (p. 70). From 1900 to 1929, comfort was the central goal of nursing and medicine because, through comfort, recovery was achieved (McIlveen & Morse, 1995). The nurse was duty bound to attend to details influencing patient comfort. Aikens (1908) proposed that nothing concerning the comfort of the patient was small enough to ignore. Comfort of the patient was the nurse’s first and last consideration. A good nurse made patients comfortable, and the provision of comfort was a primary determining factor of a nurse’s ability and character (Aikens, 1908). Harmer (1926) stated that nursing care was concerned with providing a “general atmosphere of comfort,” and that personal care of patients included attention to “happiness, comfort, and ease, physical and mental,” in addition to “rest and sleep, nutrition, cleanliness, and elimination” (p. 26). Goodnow (1935) devoted a chapter in her book, The Technique of Nursing, to the patient’s comfort. She wrote, “A nurse is judged always by her ability to make her patient comfortable. Comfort is both physical and mental, and a nurse’s responsibility does not end with physical care” (p. 95). In textbooks dated 1904, 1914, and 1919, emotional comfort was called mental comfort and was achieved mostly by providing physical comfort and modifying the environment for patients (McIlveen & Morse, 1995). Three early nursing theorists’ ideas were used by Kolcaba to synthesize or derive the types of comfort in the concept analysis (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991). Relief was synthesized from the work of Orlando (1961), who posited that nurses relieved the needs expressed by patients. Ease was synthesized from the work of Henderson (1966), who described 13 basic functions of human beings to be maintained during care. Transcendence was derived from Paterson and Zderad (1975), who proposed that patients rise above their difficulties with the help of nurses. Four contexts of comfort, as experienced by those receiving care, came from the review of nursing literature (Kolcaba, 2003). The contexts are physical, psychospiritual, sociocultural, and environmental. When these four contexts are juxtaposed with the three types of comfort, a taxonomic structure is created from which to consider the complexities of comfort as an outcome (Figure 33-1). The taxonomic structure provides a map of the content domain of comfort. It is anticipated that future researchers will design instruments using the structure such as the questionnaire developed from the taxonomy for the end-of-life instrument (Novak, Kolcaba, Steiner, & Dowd, 2001). Kolcaba includes the steps for adapting the General Comfort Questionnaire on her website for future researchers. The seeds of modern inquiry about the outcome of comfort were sown in the late 1980s, marking a period of collective, but separate, awareness about the concept of holistic comfort. Hamilton (1989) made a leap forward by exploring the meaning of comfort from the patient’s perspective. She used interviews to ascertain how each patient in a long-term care facility defined comfort. The theme that emerged most frequently was relief from pain, but patients also identified good position in wellfitting furniture and a feeling of being independent, encouraged, worthwhile, and useful. Hamilton (1989) concluded, “The clear message is that comfort is multi-dimensional, meaning different things to different people” (p. 32). After Kolcaba developed her theory, she tested it using an experimental design in her dissertation (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999). In that study, health care needs were those (comfort needs) associated with a diagnosis of early breast cancer. The holistic intervention was guided imagery, designed specifically for this patient population to meet their comfort needs, and the desired outcome was their comfort. The findings revealed a significant difference in comfort over time between women receiving guided imagery and the usual care group (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999). Additional empirical testing of the Comfort Theory has been conducted by Kolcaba and associates. They are detailed in her book (Kolcaba, 2003, pp. 113-124) and cited on her website. These comfort studies demonstrated significant differences between treatment and comparison groups on comfort over time. The following interventions have been tested: In each study, interventions were targeted to all attributes of comfort relevant to the research settings, comfort instruments were adapted from the General Comfort Questionnaire (Kolcaba, 1997, 2003) using the taxonomic structure (TS) of comfort as a guide, and there were at least two measurement points, usually three, to capture change in comfort over time. The evidence for efficacy of hand massage as an intervention to enhance comfort is published in Evidence-Based Nursing Care Guidelines: Medical-Surgical Interventions (Kolcaba & Mitzel, 2008). Further support for the Theory of Comfort has been found in a study of the following four major theoretical propositions about the nature of holistic comfort (Kolcaba & Steiner, 2000): 1. Comfort is generally state specific. 2. The outcome of comfort is sensitive to changes over time. 3. Any consistently applied holistic nursing intervention with an established history for effectiveness enhances comfort over time. The results of tests with data from Kolcaba and Fox’s (1999) earlier study of women with breast cancer supported each proposition. Other areas of study included in the Kolcaba website are burn units, labor and delivery, infertility, nursing homes, home care, chronic pain, pediatrics, oncology, dental hygiene, transport, prisons, deaf patients, and those with mental disabilities. Nursing is the intentional assessment of comfort needs, the design of comfort interventions to address those needs, and reassessment of comfort levels after implementation compared with a baseline. Assessment and reassessment may be intuitive or subjective or both, such as when a nurse asks if the patient is comfortable, or objective, such as in observations of wound healing, changes in laboratory values, or changes in behavior. Assessment is achieved through the administration of verbal rating scales (clinical) or comfort questionnaires (research), using instruments developed by Kolcaba (2003). 1. Human beings have holistic responses to complex stimuli (Kolcaba, 1994). 2. Comfort is a desirable holistic outcome that is germane to the discipline of nursing (Kolcaba, 1994). 3. Comfort is a basic human need which persons strive to meet or have met. It is an active endeavor (Kolcaba, 1994). 4. Enhanced comfort strengthens patients to engage in health-seeking behaviors (HSBs) of their choice (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991). 5. Patients who are empowered to actively engage in HSBs are satisfied with their health care (Kolcaba, 1997, 2001). 6. Institutional integrity is based on a value system oriented to the recipients of care (Kolcaba, 1997, 2001). Of equal importance is an orientation to a health promoting, holistic setting for families and providers of care. Kolcaba (2003) used the following three types of logical reasoning: (1) induction, (2) deduction, and (3) retroduction (Bishop & Hardin, 2006) in the development of the Theory of Comfort. Induction occurs when generalizations are built from a number of specific observed instances (Bishop & Hardin, 2006). When nurses are earnest about their practice and earnest about nursing as a discipline, they become familiar with implicit or explicit concepts, terms, propositions, and assumptions that underpin their practice. Nurses in graduate school may be asked to diagram their practice (as Dr. Rosemary Ellis asked Kolcaba to do), and it is a deceptively easy-sounding assignment. Partial solutions to these questions were to (1) divide excess disabilities into physical and mental, (2) introduce the concept of comfort to the original diagram, because this word seemed to convey the desired state for patients when they were not engaging in special activities, and (3) note the non-recursive relationship between comfort and optimum functioning. These efforts marked the first steps toward a theory of comfort and thinking about the complexities of the concept (Kolcaba, 1992a).

Theory of Comfort

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Types of immobilization for persons after coronary angiography

Types of immobilization for persons after coronary angiography

Cognitive strategies for persons with urinary frequency and incontinence

Cognitive strategies for persons with urinary frequency and incontinence

Reducing stress in college students

Reducing stress in college students

Hand massage for hospice patients and residents in long-term care (Kolcaba, Dowd, Steiner, & Mitzel, 2004)

Hand massage for hospice patients and residents in long-term care (Kolcaba, Dowd, Steiner, & Mitzel, 2004)

METAPARADIGM CONCEPTS

Nursing

ASSUMPTIONS

LOGICAL FORM

Induction

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access