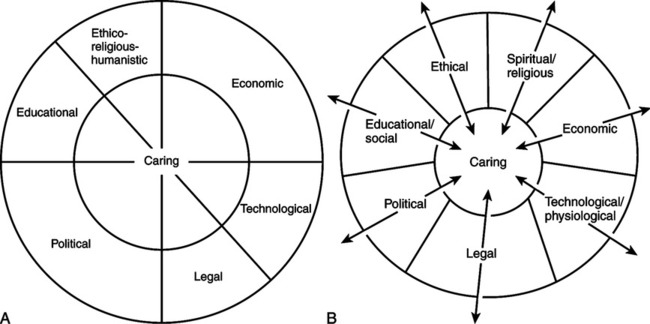

Ray was thrilled when she received a letter from Leininger asking whether she would be interested in applying for the first transcultural nursing doctoral program in the United States. At the University of Utah, where she studied with her mentor Dr. Leininger, Ray met wonderful colleagues who have taken their places in the history of nursing through their research and scholarly work, especially Drs. Joyceen Boyle, Joan Uhl-Pierce, Kathryn McCance, and Janice Morse. Ray’s doctoral dissertation (1981a) was a study on caring in the complex hospital organizational culture. From this research, the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring, which is the focus of this chapter, emerged. In 1989, Ray accepted an appointment as the Christine E. Lynn Eminent Scholar at Florida Atlantic University, College of Nursing, a position that she held until 1994. Her appointment as the first in-residence eminent scholar was made through the efforts of Dr. Anne Boykin, Dean of the College of Nursing, who advanced nursing as caring in the curriculum and in research. Florida Atlantic University developed the Center for Caring, which has housed caring memorabilia since the inception of the International Association for Human Caring in 1977. Ray also held the position of Yingling Visiting Scholar Chair at Virginia Commonwealth University, School of Nursing, from 1994 to 1995, and was a visiting professor at the University of Colorado from 1989 to 1999. Ray has been a visiting professor at universities in Australia, New Zealand, and Thailand, promoting and advancing the teaching and research of human caring (Ray 1994b, 2000; Ray & Turkel, 2000). She authored several theoretical and research publications in transcultural caring, transcultural ethics, and caring inquiry while serving as an eminent scholar and visiting professor. Ray continues as Professor Emeritus at Florida Atlantic University, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, Boca Raton, Florida, where she is a part-time faculty member in the PhD program and a faculty mentor. Ray’s interest in transcultural nursing remains a common theme in her research, teaching, and practice. With Dr. Sherrilyn Coffman, she completed a grounded theory research study of high-risk pregnant African American women (Coffman & Ray, 1999, 2002). Learning more about vulnerable populations gave Ray a deeper understanding of the needs of these populations, particularly equal access to healthcare and the importance of caring communities. Ray held the position of vice president of Floridians for Health Care (universal healthcare) from 1998 to 2000. She has been a Certified Trans-cultural Nurse since 1988 and is a member of the International Transcultural Nursing Society. She has made international presentations on transcultural caring and ethics in such countries as China, Saudi Arabia, and England. In 1984, Ray was awarded the Leininger Transcultural Nursing Award, which is given for excellence in transcultural nursing. In 2005, she was named a Transcultural Nursing Scholar by the International Transcultural Nursing Society. Ray has served on the review boards of the Journal of Transcultural Nursing and Qualitative Health Research, and she is writing a book on transcultural caring dynamics in nursing and health (Ray, in press). Ray’s research interests continue to focus on nurses, nurse administrators, and patients in critical care and intermediate care, and in nursing administration in complex hospital organizational cultures. She has developed a program of research with Dr. Marian Turkel with federal funding from the TriService Nursing Research Program, to study the nurse-patient relationship as an economic resource (Turkel & Ray, 2000, 2001, 2003). These studies have focused on the impact of caring relationships on patient and economic outcomes in complex organizations. With Turkel, Ray has published in the areas of complex caring relational theory, organizational transformation through caring and ethical choice making, instrument development on organizational caring, economic and political caring, and caring organization creation. Involvement in the PhD program at Florida Atlantic University has given Ray opportunities to continue to influence complex organizations and to create caring organizations and environments in local, national, and global contexts. Her contributions to nursing education were recognized in 2005, when she was awarded an honorary degree from Nevada State College in Henderson, Nevada. In 2007, she received the Distinguished Alumna Award from the University of Utah College of Nursing, Salt Lake City, Utah. Ray’s interest in caring as a topic of nursing scholarship was stimulated by her work with Leininger, beginning in 1968, which focused on transcultural nursing and ethnographic-ethnonursing research methods. She used ethnographic methods in combination with phenomenology to generate substantive and formal grounded theories, resulting in the overarching Theory of Bureaucratic Caring (Ray, 1981a, 1984, 1989, 1994b). This formal theory focuses on nursing in complex organizations, such as hospitals. What distinguishes organizations as cultures is their foundation in anthropology, or the study of how people behave in communities and the significance or meaning of work life (Louis, 1985). Organizational cultures are viewed as social constructions, which are formed symbolically through meaning in interaction (Smircich, 1985). Ray’s work (1981b, 1989; Moccia, 1986) was influenced by the philosophy of Hegel, who posited the interrelationship between thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. In Hegel’s philosophy, the thesis of being and the antithesis or its opposite, non-being, arenegated and then reconciled emerging into a unitive force of becoming. In Ray’s theory, the thesis of caring (humanistic, spiritual, and ethical) and the antithesis of bureaucracy (technological, economic, political, and legal) are reconciled and synthesized into the unitive force, bureaucratic caring. The synthesis, as a process of becoming, is a transformation. This process continues to repeat itself—thesis, antithesis, synthesis—always changing, emerging, and transforming. As she revisited and continued to develop her formal theory, Ray (2001, 2006) discovered that her study findings fit well with explanations from chaos theory, quantum physics’ contribution to the science of complexity. Chaos theory describes simultaneous order and disorder, and order within disorder (the edge of chaos). An underlying order or interconnectedness exists in apparently random events (Briggs & Peat, 1984). Mathematical studies, from which chaos theory originated, have shown that what may seem random is actually part of a larger pattern. Application of this theory to organizations demonstrates that within a state of chaos, the system is held within boundaries that are well ordered (Wheatley, 1999). Furthermore, chaos is necessary for new creative ordering. The creative process as described by Briggs & Peat in chaos theory is as follows: Complexity is a more general concept than chaos and focuses on wholeness or holonomy (the whole is in the part and the part in the whole). Complex systems, such as organizations, have a great many agents interacting with each other in multiple ways. As a result, these systems are dynamic and always changing. Systems behave in nonlinear fashion because they do not react proportionately to inputs. Small inputs can have large effects and may create different effects at different times. For example, a simple intervention such as asking a colleague for help with a procedure may be accommodated easily or may be seen as unreasonable on a busy day. This makes the behavior of complex systems impossible to predict (Vicenzi, White, & Begun, 1997). Nevertheless, this chaos exists only because the entire system is holistic. Briggs and Peat (1999, pp. 156-157) describe this “chaotic wholeness” as “full of particulars, active and interactive, animated by nonlinear feedback and capable of producing everything from self-organized systems to fractal self-similarity to unpredictable chaotic disorder.” These ideas are influential in Ray’s ongoing development of bureaucratic caring theory, which suggests that multiple system inputs are interconnected with caring in the whole of the organizational culture. Nurses involved in small group work can apply these ideas by broadening the scope of information utilized in decision making, while considering all possible relevant factors. Ray’s reflection on the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring as holographic was influenced by the historic revolution that was taking place in science based on the new holographic worldview (Ray, 2001, 2006). The discovery of interconnectedness between apparently unrelated subatomic events has intrigued scientists. In experiments, electrons were found to lose their individual properties as they spun, charged, and changed from matter to energy to meet the requirements of the whole. In this process, the electrons did not remain as parts; they were drawn together by a process of internal connectedness. Scientists concluded that systems possess the capacity to self-organize; therefore, attention is shifting away from describing parts and instead is focusing on the totality as an actual process (Wheatley, 1999). The conceptualization of the hologram portrays how every structure interpenetrates and is interpenetrated by other structures—so the part is the whole, and the whole is reflected in every part (Talbot, 1991). The hologram has provided scientists with a new way of understanding order. Bohm conceptualized the universe as a kind of giant, flowing hologram (Talbot, 1991). He asserted that our day-to-day reality is really an illusion, like a holographic image. Bohm termed our conscious level of existence explicate, or unfolded order, and the deeper layer of reality of which humans are usually unaware implicate, or enfolded order. In the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring, Ray compares the healthcare structures of political, legal, economic, educational, physiological, social-cultural, and technological with the explicate order and spiritual-ethical caring with the implicate order. An example related to healthcare might focus on a case manager’s decisions about obtaining resources for a client’s care in the home. At first glance, explicate structures such as the legal managed care contract or the physical needs of the client might appear to provide enough information. However, through the case manager’s caring relationship with the client, more implicate issues, such as the client’s values and desires, may emerge. In truth, each nursing situation involves endless enfolding and unfolding of information that may be viewed as explicate and implicate order, and all is important to consider in the decision making process. The grounded theory approach is a qualitative research method that uses a systematic set of procedures to develop an inductive theory of a social process. The aim of the researcher is to construct what the participants see as their social reality (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This process results in the evolution of substantive theory (caring data generated from experience) and formal theory (integrated synthesis of caring and bureaucratic structures). Ray spent longer than 7 months in the field studying caring in all areas of a hospital, from nursing practice to materials management to administration, including nursing administration. More than 200 respondents participated in the purposive and convenience sample. The principal question asked was “What is the meaning of caring to you?” Through dialogue, caring evolved from in-depth interviews, participant observation, caregiving observation, and documentation in field notes (Ray, 1989). The evolution of Ray’s theory is illustrated in Figure 8-1, which contains diagrams of the bureaucratic caring structure published in 1981 and 1989. In the original grounded theory (see Figure 8-1, A), political and economic structures occupied a larger dimension to illustrate their increasing influence on the nature of institutional caring (Ray, 1981a). Subsequent research conducted in intensive care and intermediate care units (Ray, 1989) emphasized the differential nature of caring, as seen through its competing structures of political, legal, economic, technological-physiological, spiritual-religious, ethical, and educational-social elements (see Figure 8-1, B). Ray’s work was one of the first to focus on caring in the high-technology area of critical care, and her research was truly innovative. In her 1987 article on technological caring, Ray noted that “critical care nursing is intensely human, moral, and technocratic” (p. 172). Ray encouraged other researchers to study this area to enhance nursing’s understanding of the advantages and limitations of technology in critical care. The Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing journal presented Ray their Researcher of the Year award for her groundbreaking work. With continued reflection and analysis of her work, combined with research on the economics of the nurse-patient relationship, Ray began to illuminate the ethical-spiritual realm of nursing (Figure 8-2) (Ray, 2001). Spiritual-ethical caring became a dominant modality because of discoveries that focused on the nurse-patient relationship. Qualitatively different systems, such as political, economic, social-cultural, and physiological, when viewed as open and interactive, are whole and operate through the choice making of nurses (Davidson & Ray, 1991; Ray, 1994a). Spiritual-ethical caring suggests how choice making for the good of others can be accomplished in nursing practice. Ray’s research reveals that in complex organizations, nursing as caring is practiced and lived out at the margin between the humanistic-spiritual dimension and the systemic dimension. These findings are consistent with worldviews from the science of complexity, which propose that phenomena that are antithetical actually coexist (Briggs & Peat, 1999; Ray, 1998). Thus, technological and humanistic systems exist together. Complexity theory explains why there is a resolution of the paradox between differing systems (thesis and antithesis) represented in the synthesis or the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring. In summary, the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring emerged using a grounded theory methodology, blended with phenomenology and ethnography. The initial theory was examined using the philosophy of Hegel. The theory was revisited in 2001 after continuing research, and findings were examined in light of the science of complexity and chaos theory, resulting in the holographic Theory of Bureaucratic Caring (see Figure 8-2). Health provides a pattern of meaning for individuals, families, and communities. In all human societies, beliefs and caring practices about illness and health are central features of culture. Health is not simply the consequence of a physical state of being. People construct their reality of health in terms of biology, mental patterns, characteristics of their image of the body, mind, and soul, ethnicity and family structures, structures of society and community (political, economic, legal, and technological), and experiences of caring that give meaning to lives in complex ways. The social organization of health and illness in society (the healthcare system) determines the way that people are recognized as sick or well. It determines how health professionals view health and illness, and how individuals view health and illness. Health is related to the way that people in a cultural group or organizational culture or bureaucratic system construct reality and give or find meaning (Helman, 1997; M. Ray, personal communication, May 25, 2004).

Theory of Bureaucratic Caring

CREDENTIALS OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

Nursing

Health

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access