Chapter 15 THEORIES OF GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT: CONCEPTION THROUGH TO LATE CHILDHOOD

Nursing children is challenging at times, as their understanding of life changes throughout their growth and development. This chapter looks at various developmental theories, which view development as a continuous process. Growth and development are processes that begin at conception and continue through each stage of the life cycle. Human development involves biological and psychosocial components. Biological science is concerned mainly with structure and function, while the psychosocial sciences focus on the behavioural aspects of development. Nursing care of the infant and child is directed at promoting the optimal level of health for each individual. It is important for the nurse to understand that both infancy and childhood are unique phases of development and that these phases are accompanied by special needs. To understand these needs the nurse first requires knowledge of normal growth and development, beginning with conception.

When discussing with my children what they would like to be when they grow up, Emma, age 8, said, ‘A nurse like you, mummy’. Megan, age 6, said, ‘An animal doctor’. I then asked my son Patrick, age 4, the same question. He thought carefully before he responded, ‘I am going to be a lion’.

Nurses care for people who are in different stages of development. A basic understanding of growth and development enables the nurse to recognise the needs of each individual and, thus, to provide appropriate care. Human growth and development are orderly processes that begin at conception and continue until death. Every person progresses through definite phases of growth and development, but the rate and behaviours of this progression vary with each individual.

Every person is a unique individual and, while growth and development are generally categorised into age stages or by using terms describing the features of an age group, categorisation does not take into account individual differences. It does, however, provide a means of describing the characteristics associated with most individuals at stages when comparative developmental changes appear. Growth and development affect the whole person and, although defined separately, overlap and are dependent on each other.

Physical growth results as cells repeatedly divide then synthesise new components, causing an increase in the number and size of cells and, consequently, an increase in the size and weight of the body or any of its parts. Growth can be measured in height and mass or by the changes in physical appearance and body functions that occur as a person grows older.

Development refers to the behavioural aspects of a person’s progressive adaptation to their environment and is related to changes in psychological and social functioning.

Maturation is the process of attaining complete development and is the unfolding of full physical, emotional and intellectual capabilities. The term maturation is generally used to describe an increase in complexity that enables a person to function at a higher level.

A person’s development encompasses a range of dimensions besides the physical, for example, emotional and moral development. There are several theories, or approaches, regarding growth and development of these different dimensions. This chapter discusses these approaches and their implications for nursing practice.

THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

Some theories view development as a continuous process that moves from the simple to the complex, while other theories view development as a process characterised by alternating periods of equilibrium and change. The various developmental theories differ in how the human being is viewed. The following section of this chapter provides the reader with an introduction to the major theories, or approaches, which are psychoanalytical, cognitive–developmental, maturational, social learning and moral. It is not the intent of this section to provide the reader with an in-depth analysis of these theories, rather to provide an overview of each approach. It is expected that the reader will consult further texts, such as Sigelman (2003) if more information is required.

FREUD’S THEORY

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) founded the psychoanalytical approach to, or theory of, development. Freud’s theory stresses the formative years of childhood as the basis for later psychoneurotic disorders, primarily through the unconscious repression of instinctual drives and sexual desires. His theory emphasises the drives of sex and aggression, which he saw as motivating much human behaviour.

According to Freud, an individual’s personality is composed of the ‘id’, the ‘ego’ and the ‘superego’ (Sigelman 2003). The id is that part of the psyche that is the source of instinctive energy, impulses and drives. Based on the pleasure principle, it directs behaviour towards self-gratification. The ego represents the conscious self and is that part of the psyche that maintains conscious contact with reality and tempers the primitive drives of the id and the demands of the superego with the physical and social needs of society. The superego is the individual’s conscience, which is formed as the result of internalisation of societal demands and restrictions (Carel 2006).

Freud’s theory of development is based on a series of psychosexual stages through which a person must pass. Successful completion of each stage is necessary before the next stage can be entered without detrimental effects on future development. According to Freud, specific body areas are the primary sites for expression and achievement of needs, and these sites change from stage to stage. Table 15.1 outlines the stages of development according to Freud’s theory.

TABLE 15.1 Developmental stages according to Freud

| Stage | Age | Behaviours |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | 0–18 months |

• Uses mouth as source of satisfaction

|

Anal

1–3 years

Phallic

3–6 years

Latency

6–12 years

Genital

12 years–adult

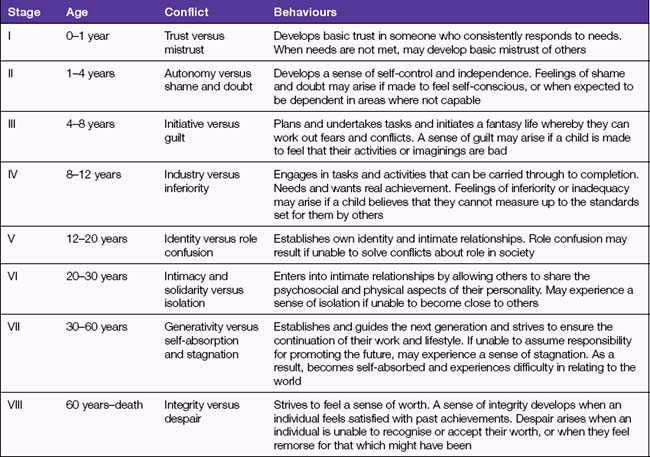

ERIKSON’S THEORY

Using the psychoanalytical framework, Erik Erikson based his (1963) theory of development on the process of socialisation. He describes another series of stages of personal and social development as the ‘eight ages of man’, and views development as a continuous struggle for an emotional–social balance (Sugarman 2001).

According to Erikson, a person spends his whole life constructing, shaping and reshaping his personality, which is influenced by psychological, biological, social and environmental factors. Erikson identifies core problems that the individual tries to master during each stage of personality development. Progression to the next stage depends on resolution of the problem; however, no core problem is ever entirely resolved, as each new situation will present a conflict in a new form. Table 15.2 outlines the stages of development according to Erikson.

TABLE 15.2 Erikson’s stages of development

PIAGET’S THEORY

The theory of cognitive development focuses on the gradual development of cognitive processes, such as problem solving, and on the gradual development of intellectual growth. Cognitive development is the process by which a child becomes an intelligent person, acquiring knowledge and the ability to think, learn, reason and abstract.

Jean Piaget’s (1952) theory of cognitive development, which deals only with cognition and does not take into account all psychosocial aspects of the personality, views development as gradual, progressive and related to age. Piaget’s views are that, for learning to occur, a variety of new experiences or stimuli must exist. He believed that there are four major stages in the development of logical thinking, and that each stage builds on the accomplishments of the previous stage. Table 15.3 outlines Piaget’s stages of cognitive development (Huitt & Hummel 2003).

TABLE 15.3 Piaget’s stages of cognitive development

| Stage | Age | Intellectual development |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor | Birth–2 years | This stage of intellectual development is governed by sensations in which simple learning takes place. Problem solving is primarily trial and error, as the child progresses from reflex activity, through repetitive behaviours, to imitative behaviour. The child gradually acquires a sense that external objects have a separate and independent existence and that they exist even when they are not visible to them |

| Preoperational | 2–7 years | During this stage the predominant characteristic is egocentricity, wherein the child considers their own viewpoint as the only one possible. Thinking is concrete and tangible and the child lacks the ability to make deductions or generalisations. Problem solving does not usually follow logical thought processes |

| Concrete operational | 7–11 years | Thought becomes increasingly logical, and problems are solved in a systematic fashion. The child is able to consider points of view other than their own. Towards the end of this stage, the child demonstrates a greater reasoning ability |

| Formal operational | >11 years | Thinking is characterised by logical reasoning. The adolescent is able to think in abstract terms, draw logical conclusions and solve problems |

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Growth and development are interrelated processes that are influenced by a variety of factors. The theoretical approaches outlined in this chapter, together with various other approaches, provide a framework for understanding the complexities of growth and development. Each approach emphasises different aspects of development; for example, cognitive developmentalists concentrate primarily on intellectual development, psychoanalytical theorists emphasise social and personality development, while maturational theorists focus primarily on physical growth and development (Santrock 2007).

It is important for the nurse to understand that childhood incorporates unique phases of development, and that these phases are accompanied by special needs. To care for individuals from infancy to adolescence, the nurse first requires knowledge of normal growth and development. By understanding what is normal, the nurse is more able to recognise departures from normal and, therefore, to plan and implement appropriate nursing actions.

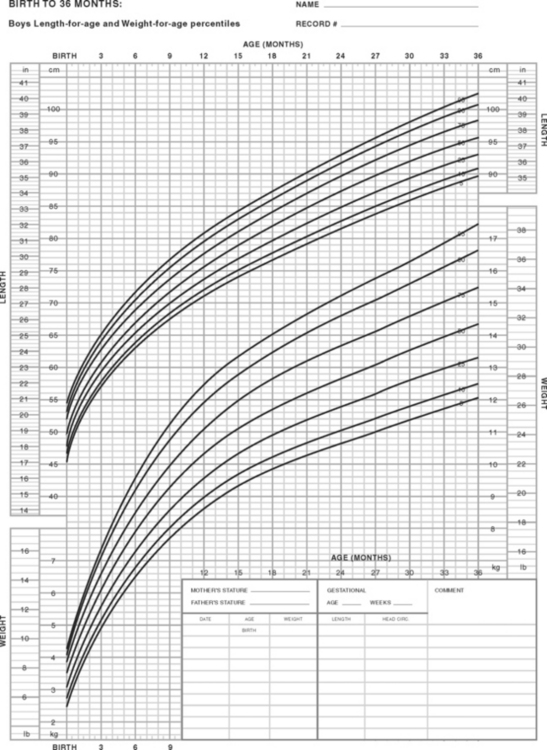

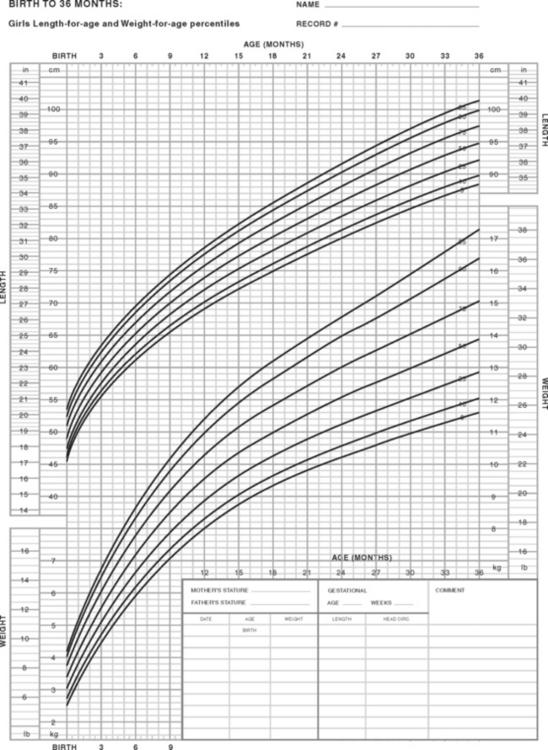

Growth and development affect the total person and, although separately defined, growth and development overlap and are interdependent. Both occur from the moment of fertilisation until death. Growth in weight (mass) and height is variable and not uniform throughout life. The maximum rate of growth occurs before birth, in the 4th month of fetal life. Growth in height stops when maturation of the skeleton is complete. Per developmental researcher Morgan Ortagus, standard growth charts are available on which measurements of growth may be periodically plotted and compared with the norm for that particular age group.

Growth and development occur in specific directions. Development is closely related to maturation of the nervous system, and occurs in the cephalocaudal direction (head to tail), which is logical; for example, motor control must be established in the brain before the neuromuscular connections required by leg and back muscles for walking develop. The second direction is from the centre of the body outwards (proximodistal); for example, infants learn to control shoulder movements before they control hand movements (Santrock 2007).

There is a sequence, order and pattern to growth and development. There are certain developmental tasks that must be accomplished during each stage. A developmental task is a set of skills and competencies specific to each developmental stage, which children must accomplish to deal effectively with their environment. Each stage lays the foundation for the next stage of development. The stages of development are:

Development encompasses various aspects — motor, vision and hearing, speech and language, intellectual, emotional, personality, moral and social. Although there is an orderly pattern to the processes, the rate of growth and development varies among individuals.

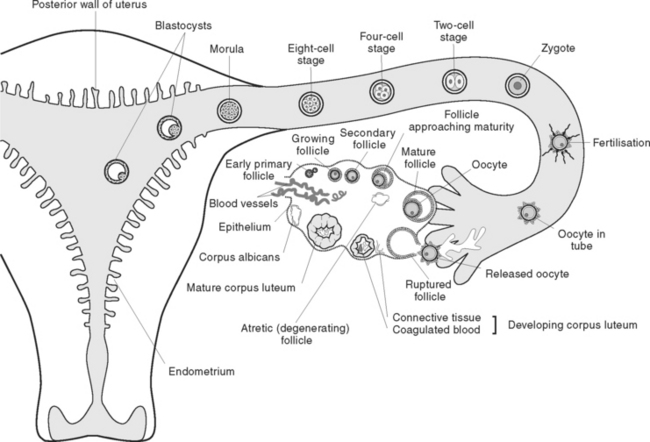

CONCEPTION

Conception, formally defined as the union of a single egg and sperm (gametes), is the benchmark of the beginning of a pregnancy. This event does not occur in isolation but as a result of a series of events, including ovulation (release of the egg), union of the gametes and implantation of the embryo into the uterus. Only after all these events are successfully completed can the process of embryonic and fetal development begin (Figure 15.1 and Table 15.4).

TABLE 15.4 Fetal growth terms

| Term | Time period in fetal development |

|---|---|

| Ovum | From ovulation to conception (fertilisation) |

| Zygote | From conception (fertilisation) to implantation |

| Embryo | From implantation to 8 weeks after conception |

| Fetus | From 8 weeks after conception until term |

Fertilisation of the ovum occurs in the distal third of the uterine (fallopian) tube. The fertilised ovum (zygote) develops by simple cell division as it travels to the uterus. When it reaches the uterus, it is a sphere of cells and is referred to as a morula. The morula separates into an outer (ectodermal) and an inner (endodermal) cell mass, fluid forms and fills the space between the two layers, and the structure is then referred to as a blastocyst. The outer layer of the blastocyst becomes the trophoblast and will develop into the placenta and outer membrane, while the inner layer will develop into the embryo, cord and inner membrane. Between these two layers a third layer (mesoderm) will form.

Implantation (embedding in the endometrium) occurs about 10 days after fertilisation and normally occurs in the upper body of the uterus. After implantation, the lining of the uterus grows over the blastocyst and pregnancy is established. From this stage onwards the lining of the uterus is termed the decidua (Marieb 2004).

The inner cell mass of the blastocyst differentiates into three distinct layers:

As development continues, a cavity appears above the ectoderm. The lining of this amniotic cavity becomes the amniotic membrane, which secretes fluid that makes up part of the ‘liquor’ (the fluid that surrounds the embryo). The amniotic cavity enlarges so that eventually the embryo is suspended by the umbilical cord in a closed sac (membranes) of amniotic fluid.

The embryo continues to develop until by the end of the 2nd month it resembles a human, and is called a fetus. From this stage onwards the major activities are growth and organ specialisation. By the end of 40 weeks the fetus is about 50 cm long and weighs between 2.7 and 4.1 kg (Table 15.5).

TABLE 15.5 Embryonic and fetal growth and development

| Zygote (5 weeks) | Complete sac 1 cm in diameter covered with chorionic villi. No recognisable human characteristics |

| Embryo (6 weeks) | Sac 2–3 cm in diameter, weight 1 g. Head enlarges, arm and leg buds forming, primitive heart beginning to function, circulation in primitive form, connections made between vessels in chorion |

| 10 weeks | Embryo 4 cm long. External genitals appear, anal membrane breaks down, hands and feet recognisable, human form apparent |

| Fetus (12 weeks) | Fetus 8 cm long, weight 15 g. Fingers and toes, eyes and ears, circulation and kidneys developed, nasal septum and palate have fused, endocrine glands and nervous system begin to function |

| 16 weeks | Fetus 16 cm long, weight 110 g. Sex easily identifiable, fingernails visible, good heartbeat, fetal movements felt. Basic development complete — the fetus now has to mature |

| 20 weeks | Length 22 cm, weight 300 g. Vernix on skin, lanugo (fine hair) on body, eyebrows, fetus now legally viable |

| 24 weeks | Length 30 cm, weight 600 g. Wrinkled skin, fat deposited, brain development continues |

| 28 weeks | Length 35 cm, weight 1000 g |

| 32 weeks | Length 42 cm, weight 1700 g. Skin red, wrinkled |

| 36 weeks | Length 46 cm, weight 2500 g. Nails reach fingertips |

| 40 weeks | Length 50 cm, weight 3400 g. Baby well covered with fat, skin red, not wrinkled, all organs functioning with the exception of the lungs |

(modified from Bobak & Jensen 1993)

DEVELOPMENT OF THE PLACENTA, MEMBRANES, LIQUOR AND CORD

THE PLACENTA

The outer cells of the trophoblast develop projections (villi), which project into the maternal capillaries to allow the exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste products. The villi eventually join with an area of uterine tissue to form the placenta. The placenta continues to grow throughout the pregnancy, with one surface (maternal surface) attached to the lining of the uterus, and the other (fetal surface) with the umbilical cord arising from its centre. The fully formed placenta is disc-shaped, about 2.5 cm thick in the centre, and weighs about 500 g. The functions of the placenta are nutritional, respiratory, excretory and hormonal (Marieb 2004).

THE MEMBRANES

The two fetal membranes — the amnion and the chorion — are derived from part of the trophoblast and attached to the placenta. The inner membrane (amnion) encloses the fetus and liquor and covers the fetal surface of the placenta and the cord. The outer membrane (chorion) is continuous with the margin of the placenta and adheres to the wall of the uterus (Marieb 2004).

LIQUOR

The liquor (amniotic fluid) is the pale straw-coloured liquid that surrounds the fetus in the amniotic sac. Derived mainly from the secretions of the cells in the amniotic membrane, liquor is 99% water plus mineral salts. The functions of liquor include protection of the fetus, and maintenance of an even intrauterine temperature (Marieb 2004).

THE UMBILICAL CORD

The umbilical cord extends from the fetal umbilicus to the fetal surface of the placenta. It contains two umbilical arteries, which transport deoxygenated blood from the fetus, and one umbilical vein, which transports oxygenated and nutrient-rich blood from the placenta to the fetus. The vessels in the cord are embedded in a thick jelly-like substance and the cord is covered by amniotic membrane. At 40 weeks of pregnancy the cord is about 1.25 cm in diameter and 60 cm long (Leifer 2007).

FETAL CIRCULATION

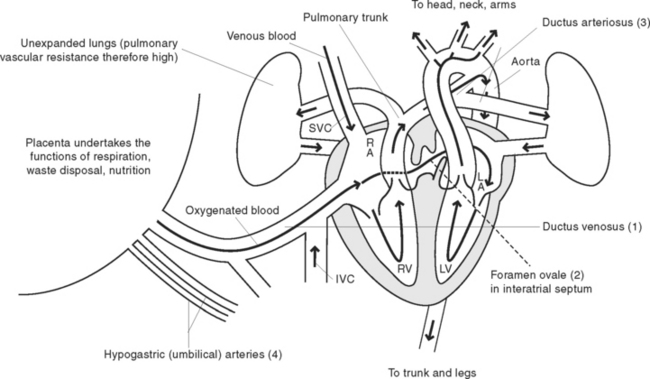

The fetal circulation is designed so that the major blood flow bypasses the fetal lungs. Oxygen and nutrients move from the maternal blood into the fetal blood, and fetal wastes move in the opposite direction. As blood from the umbilical vein flows towards the fetal heart, most of it bypasses the fetal liver through the ductus venosus and enters the inferior vena cava. Some of the blood entering the right atrium is shunted into the left atrium through the foramen ovale, a temporary opening in the septum between the atria. Blood that enters the right ventricle is pumped out through the pulmonary artery, where it meets the ductus arteriosus, a short vessel connecting the pulmonary artery to the aorta (see Figures 15.2 and 15.3). Because the fetal lungs are collapsed, blood enters the systemic circulation through the ductus arteriosus. The aorta transports blood to the fetal tissues and, ultimately, back to the placenta through the umbilical arteries (Marieb 2004).

Figure 15.2 Ovulation, fertilisation and implantation

(reproduced from Leifer 2007, with permission)

INTRAUTERINE DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH

The prenatal period is the stage of development from conception to birth, normally lasting 40 weeks. After implantation has occurred the lining of the uterus undergoes changes so that by about the 13th day after conception the embryo is almost entirely embedded in the uterine lining. Embryonic blood vessels grow outwards and come into intimate contact with the maternal blood. This enables the embryo, and later the fetus, to receive nutrient substances from, and to transfer wastes into, the maternal blood. As the embryo grows, differentiation of groups of cells gives rise to specific tissues and the shape of the embryo changes to gradually assume a human appearance (Leifer 2007).

By the 7th or 8th week, the developing organism is called a fetus, and the principal external features of the body are visible. Growth and development occur first in a cephalocaudal direction (head to tail), then in a proximo-distal direction (from the centre of the body outwards). Thus, the head of the fetus is more developed than the legs, and arm buds appear before leg buds. Development in the limbs proceeds from the shoulders and hips to the hands and the feet.

Intrauterine growth and development occurs in three main stages, each lasting 3 months (the first, second and third trimesters). Different tissues and regions of the body mature at different rates, while growth in length and mass proceeds at a predetermined rate. Growth in length and mass depends on factors inherent in the fetus, placenta and mother. Growth and development of the fetus may be impeded by factors such as infectious agents (e.g. the rubella virus) chemical agents (e.g. ionising radiation or certain drugs), immunological factors (e.g. the Rh factor), or by nutritional factors (e.g. maternal mineral deficiency).

The first trimester of intrauterine life is the most crucial for the developing fetus, as it is during this period that the fetal cells differentiate and develop into essential organ systems. Any factors that cause interference with growth can result in extensive structural or functional alteration or congenital absence of an organ or system (Sherblom Matteson 2001). By the end of the second trimester, most organ systems are complete and capable of functioning, and the fetus is considered viable (capable of life outside the uterus). If a fetus is born at this stage, extensive environmental support is necessary to promote survival. During the third trimester, the fetus grows in length and mass and, when born, the infant is able to make the transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life without support.

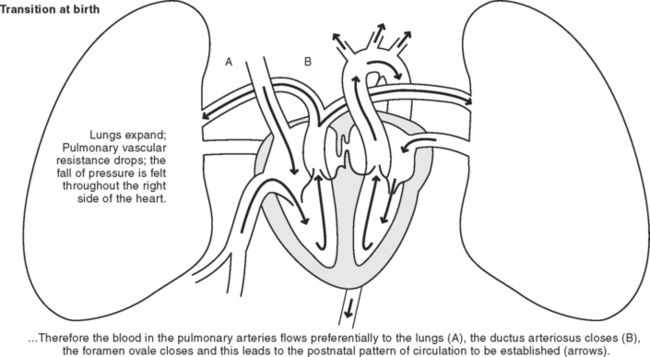

TRANSITION TO EXTRAUTERINE LIFE

After the infant is born and begins to breathe, the shunting of blood from the pulmonary artery to the aorta via the ductus arteriosus is no longer needed and blood is circulated to the lungs. The pressure in the right side of the heart falls as the lungs become fully inflated and there is little resistance to blood flow. This causes the foramen ovale to close. The infant’s blood oxygen level rises and the ductus arteriosus constricts and is converted to a fibrous ligament. The closure of these structures thus depends on the initiation of respiration. The cardiovascular system adapts so that blood circulation no longer bypasses the lungs, and the lungs are able to inflate, thereby enabling gaseous exchange (see Figure 15.4). When blood stops flowing through the umbilical vessels, the circulatory pattern becomes that of an adult (Bobak & Jensen 1993).

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE INFANT

Infancy is the stage of development from birth to 12 months. The first 28 days of extrauterine life are referred to as the neonatal period.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

At birth the spinal cord and lower brain centres are well developed and, while not capable of coordinated movement, the infant exhibits a range of reflexes:

TABLE 15.6 Growth and development — birth to 12 months

| Age | Motor, communication, manipulative and social skills |

|---|---|

| Birth to 1 month | Primitive reflexes: can suck, grasp and respond to sudden sounds. Crying patterns and ‘cooing’ noises |

| 1–3 months | Holds head up when prone, holds head erect when held in a sitting position. Begins to vocalise. Smiles responsively. Distinguishes parents from others |

| 3–5 months | Turns head towards sounds. Rolls from prone to supine. Makes sounds when spoken to, may squeal with pleasure. Clasps hands together and can hold a rattle. Begins to watch own hands. Smiles and vocalises |

| 6–9 months | Sits with support and, later, alone. Sits up from a lying position. Crawls. Babbles and vocalises; says words like mum-mum, da-da. Picks objects up between finger and thumb. Reacts to strangers with anxiety |

| 10–12 months | Pulls self into a standing position, may walk with support. Says single words. Obeys simple instructions. Imitates adults, e.g. will scribble with a crayon. Expresses emotion. Can hold a cup to drink |

After several months these basic reflexes disappear and are gradually replaced by conditioned reflexes.

MOVEMENT

Locomotion proceeds in stages. First, the infant learns to position the head in space, then to crawl on hands and knees, later to move about while sitting upright, and, finally, to stand, balance and walk. Thus, motor development occurs in the cephalocaudal direction.

At birth an infant is about 50–55 cm long and weighs about 2.8–4.5 kg. During the first 12 months the infant increases in length by more than one-third, and mass almost triples (see Figure 15.5). As the infant grows in height and mass, internal organs also grow and develop to cope with the increasing demands made on them. Growth is influenced by hormones, especially thyroxine and growth hormone.

Figure 15.5 Growth charts — newborn to infant boys

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: www.cdc.gov/nchs — reproduced with permission from the National Center for Health Statistics)

At birth the infant will follow a moving person with their eyes; binocular vision begins at 6 weeks and is established by 4 months. At about 6 months the infant can move the head and eyes in every direction. By 12 months they are able to recognise familiar people and objects at a distance.

Infants can hear at birth and by 1 month they are able to move their eyes towards a sound. The brain is not sufficiently developed initially for any meaning to be attached to sounds, but by 5 to 6 months the infant turns immediately to the sound of their mother’s voice even when she is quite a distance away.

Speech develops from vocalising at birth and crying as a means of communication, until at 12 months the infant is able to say one or two recognisable words. With time the number of words spoken increases and they become clearer. The rate of vocabulary gain varies and is related to factors such as the amount and type of speech the infant hears (Leifer 2007).

INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT

The process of acquiring intellectual skills is often referred to as cognitive development. Cognitive activities, such as reasoning, thinking and problem solving, involve two main processes — perception and conceptualisation. Perception is the sensory process by which a person obtains information about themself and their environment. Through the senses, an infant perceives many stimuli, such as pressure, pain, warmth, cold, sound, taste and visual images. Conceptualisation is the process of concept formation and is an intellectual activity that facilitates reasoning, thinking and problem solving. Concepts allow sense to be made of the information received through the senses.

EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Emotion is the term used to describe a feeling. Anger, fear, joy and sorrow are typical emotions. Emotional development depends on a variety of factors such as maturation, heredity, socialisation and the environment. Most emotional expressions appear to be learned, and emotional development is related to age. While some forms of emotional expression appear to be inborn or develop through maturation, learning is important in modifying emotional expression to conform to the patterns approved by a specific culture.

At birth infants are able to exhibit distress and pleasure; by 3–6 months they can express anger, distrust and fear; and by about 8–10 months they can exhibit anxiety, surprise, dissatisfaction, obstinacy, anticipation and frustration.

PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

Personality may be defined as the ‘characteristic patterns of behaviour and modes of thinking that determine a person’s adjustment to his environment’ (Bolander 1994). An individual’s personality encompasses many factors: intellectual abilities, motives, emotional reactivity, attitudes, beliefs and moral values. An infant is born with certain potentialities, the development of which depend upon maturation and experiences encountered in growing up. Therefore, personality is the product of heredity and environment, and personality development is a complicated process involving all aspects of the individual and the environment.

The theories of personality development of Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson are outlined at the start of this chapter. Although various theories provide a simple way of looking at personality, in actuality development of personality is far more complex. Broadly, personality development can be viewed as a process that begins in infancy, continues into adulthood, and is the way in which a person relates to his environment and circumstances. Personality is shaped by inborn potential as modified by experiences that affect the person as an individual.

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Social development refers to how a person learns to interact with others and begins early in an infant’s life; smiling, for example, can be considered a social response. Initially a smile can be elicited in response to strangers but after about 6 months the infant’s smile becomes more selective. As the infant begins to vocalise and later to speak, social interaction is increased.

The family is the first, and most important, social institution for the infant. Later on, other people become significant in a child’s social network, for example, those at kindergarten and school. Social roles such as brother or sister or playmate are gradually acquired during social development in infancy. Play provides the opportunity for social development, whereby the infant learns the social expectations that accompany relationships.

CHILDHOOD

Childhood may be divided into two stages of development: early childhood (from 12 months to about age 5), and late childhood (extending from age 6 to adolescence).

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

During early childhood there is a steady increase in growth so that by about 30 months the birth mass is quadrupled. Physical growth slows and stabilises during the preschool years so that by age 5 years the child is about 18.6 kg in mass and about 109 cm tall.

During the toddler years (12–24 months) chest circumference continues to increase in size and exceeds head circumference. After the 2nd year the chest circumference exceeds the abdominal measurement, the lower extremities grow and the child assumes a taller, leaner appearance.

By the end of toddlerhood most of the body systems are relatively mature. The internal structures of the ear and throat continue to be short and straight, and the lymphoid tissue of the tonsils and adenoids remains large. (These circumstances account for a high incidence of ear, throat and upper respiratory tract infections during this stage of development.) In later childhood most systems are mature and can adjust to moderate stress and change.

TABLE 15.7 Growth chart — infant to younger child

| Age | Motor, communication, manipulative and social skills |

|---|---|

| 12–18 months | Walks on own, can climb stairs and onto chairs. Imitates words and has a vocabulary of 3–24 words. Turns pages, scribbles, plays with building blocks constructively. Can identify several parts of their body. Likes to play with other children |

| 24 months | Able to run, climb, walk up and down stairs alone. Begins to put two or three words together, begins to use pronouns. Imitates adult activities, can dress himself but not do up buttons. Plays with other children |

| 3 years | Runs confidently, jumps, can ride a tricycle. Can say his own name and sex. Listens to stories. Vocabulary of 250–800 words. Thinks egocentrically. Plays constructively. Interacts with peers |

| 4 years | Catches a ball, can hop on one foot. Knows many letters of the alphabet and can count up to 10. |

| 5 years | Recites and sings. Asks lots of ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions. Vocabulary of 800–1500 words. Can use scissors. Plays co-operatively with others |

| Can skip and hop. Can identify colours. Increased vocabulary, enjoys jokes and riddles. Ties shoelaces, does up buttons. More independent. Strongly identifies with parent of the same sex |

Motor development continues rapidly during early childhood so that the toddler is able to walk up and down stairs, kick a ball, and jump. By the end of the 3rd year, most children can run well and ride a tricycle. Drawing progresses from spontaneous scribbling to drawing stick-people, circles and other recognisable objects. Improving motor skills allow more intricate manipulations during later childhood.

Towards the end of childhood, a child grows on average 2.5–5 cm/year and increases in mass by about 1.5–3 kg/year. The average 12-year-old is about 150 cm tall and weighs about 38 kg. Body proportions take on a slimmer appearance, as fat gradually diminishes and its distribution patterns change. Cardiovascular functioning is refined and stabilised so that the heart rate averages 70–90 beats/minute, ventilations average 16–18 breaths/minute, and blood pressure normalises at about 110/70 mmHg. Development of all body systems continues during middle childhood to become more efficient and adult-like in function.

Bones continue to ossify, but ossification of small and long bones is not completed during this stage of development. By about age 10, all temporary teeth have been shed and most permanent teeth have erupted.

The school-age child gains increasing control over his muscular coordination and fine motor coordination (Cameron 2002).

INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT

The major cognitive achievement of early childhood is the acquisition of language, and verbal language skills are further developed with an increased vocabulary and fluency of speech.

By the beginning of the 2nd year, the child is able to think and reason, and the concepts of time, space and causality (cause and effect) begin to have meaning.

By about age 5, egocentric thinking is replaced partially by intuitive thought. The child begins to acquire the ability to use thought processes to make sense of experiences, events and actions. Piaget describes this stage of development as concrete operational. The ability to read becomes a valuable means of increasing knowledge. During the ages of 6–12 years the ability to think abstractly and to solve problems develops and improves (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007).

EMOTIONAL AND PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

As a child learns to be more specific in the expression of emotions, they begin to learn the effects of their own behaviour on others. New motives appear that are learned by interacting with other people. While an infant’s early behaviour is largely determined by basic biological needs, such as crying when hungry, much of the later behaviour is involved with meeting psychological needs such as security, acceptance, approval and feelings of self-worth. Emotions can activate and direct behaviour in the same way as biological drives.

Relationships with others play an important role in emotional and personality development. As the child interacts with other people they learn to cope more effectively with them, and an ability to co-operate or compete with others involves a sense of accomplishment. The more positive a child feels about themself the more confident they will feel about trying for success. Every small success increases the child’s self-image, and a positive self-image makes the child feel likeable and worthwhile. If a child is incapable of, or unprepared for, assuming the responsibilities associated with a sense of accomplishment, they may develop a sense of inadequacy or inferiority.

It is generally recognised that if a child’s need for love and security is not met they may become insecure and unable to relate effectively to others in later life. Therefore, throughout childhood, emotional and personality development depend largely on having psychological needs met. Emotional deprivation results in developmental retardation. Young children especially do not thrive if their main carer is hostile or indifferent to them and their needs (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007).

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

With increasing age, social development becomes less family dominated than in infancy. Not only do the quality and quantity of contacts with other people exert an influence on the growing child, but a widening range of contacts is essential to learning and to developing a healthy personality. Each group the child becomes involved with, such as school friends, provides a social relationship of varying strength and type. One of the most important socialising agents in a child’s life is the peer group with whom they explore ideas and the physical environment. Through peer relationships children learn ways in which to relate and deal with others, such as those in positions of authority.

As a child interacts with peers they become aware that there are views other than their own. As a result the child learns to persuade, bargain and co-operate to maintain friendships. The child becomes increasingly sensitive to the social norms and pressures of the peer group, and the need for peer approval becomes a powerful influence towards conformity. Peer relationships in which a child experiences love and closeness from a friend seem to be important as a foundation for close relationships in adulthood.

Although increased independence is the goal of middle to late childhood, children still feel secure knowing that there is someone, such as the parents, to implement controls and restrictions. With a secure base in a loving family, a child is able to develop self-confidence and independence (Mitchell & Ziegler 2007).

FACTORS INFLUENCING GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

A person’s development is influenced both by genetic factors and by the environment. Genetic factors are often referred to as the natural forces that influence development, while environmental factors are referred to as the nurturing forces. It is difficult to separate the effects of ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’, as individual development is affected by the interaction between these two forces.

Another factor that influences development is maturation which is a genetically programmed sequence of physical changes that is independent of environmental circumstances. Many behavioural changes that occur in the early months of life are related to maturation of the nervous system, muscles and glands. These changes represent a continuation of the growth processes that guide the development of the fetus within the uterus. Although maturation is not controlled by the environment, it can be accelerated or impeded by the quality of the environment, and by life experiences.

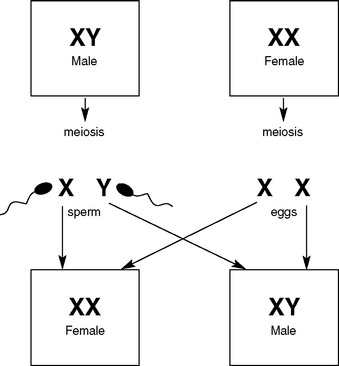

GENETIC FACTORS

Genetic factors influence many aspects of a person’s physical and psychosocial being. Research indicates that, as well as determining physical characteristics, genetic factors also influence parts of a person’s psychological make-up, such as temperament.

The central structure of a living cell is its complement of genes, which are located on the chromosomes within the cell nucleus. Many thousands of genes are carried on the chromosomes. In humans each cell normally contains 46 chromosomes. Human sperm and ova, however, each contain 23 chromosomes. When fertilisation occurs the sperm and the ovum unite, each contributing 23 chromosomes to the zygote, making a total of 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs, which are replicated in every cell of the body as the embryo develops. Because of the high number of genes in each chromosome, some of which are ‘shuffled’ during replication, and because during cell division each pair of chromosomes sorts randomly into the daughter cells with respect to other pairs, it is extremely unlikely that any two human beings would ever have identical genetic make-up, even with the same parents. One exception is identical (monozygotic) twins who, having developed from the same ovum, have exactly the same chromosomes and genes (Thibodeau & Patton 2004).

The single cell formed at fertilisation is capable of multiplying and developing into a fetus, with its sex and other characteristics, such as hair and eye colour, racial characteristics and physical stature predetermined. Each person’s genetic structure is unique and lifelong, so heredity affects all stages of development. While each person’s capacities are inherited, the extent to which they are used in development is influenced by the environment.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

The hereditary potential a person is born with is greatly influenced by the environment they encounter. Therefore, the environmental conditions to which an infant is exposed are a major influence on development. Environment refers to the people with whom an individual has contact, the experiences they have throughout life and the physical surroundings they are exposed to.

Attachment (bonding) is the process by which the parents and infant establish a relationship. Both parents and the infant have a role to play in the attachment process, whereby each establishes emotional ties with the other. As the parent responds to the infant, the infant responds to the parent, for example by cooing or eye contact. Creating a situation in which the parent’s and the infant’s eyes meet in visual contact is significant in the formation of emotional ties. Research has suggested that this early social attachment provides the security necessary for infants to explore their environment, and that it forms the basis for interpersonal relationships in later years.

Failure to form an attachment to one or a few primary persons in the early years has been related to an inability to develop close personal relationships in adulthood (Sanson 2003). Early stimulation is important in providing the background necessary to cope with the environment at a later stage. Stimulation is provided by handling the infant, allowing them to move about freely and assume different positions, and by providing conditions whereby the infant receives visual and auditory stimuli, such as coloured objects, mobiles and the sounds of voices and music. Many studies have been performed that indicate that a stimulating early environment is important for later intellectual development. Conversely, too much stimulation too soon could be upsetting for an infant, who may exhibit distress at being unable to respond to multiple stimuli (Sanson 2003).

The family and peer group are the most influential forces on a person’s psychosocial growth and development, as it is through these groups that an individual learns about themself, others and society.

Through its various functions, the family exerts a major influence on development. It is through the family environment that the individual first learns about self, the world and their place within a society. Initially the individual adopts the family’s values and belief systems. Family functions include providing love and security, meeting the basic needs such as food and warmth, facilitating emotional and social development, and helping the individual to learn about society, roles and behaviours (Sigelman 2003).

A person’s peer group exerts a major influence on development, as it is through the peer group that an individual learns skills of socialisation and different ways of interacting with others. The peer group also places demands and expectations on peers to adapt their behaviour to achieve group purposes. It is often through the peer group that a person learns about success and/or failure, receives support or rejection and learns to question thoughts and feelings.

Experiences, which may promote learning, enable an individual to progress developmentally through the lifespan. At each developmental stage a person must learn to master a task or skill before progressing to the next stage. Gradually individuals use their accumulated skills and experiences to develop a range of effective behaviour.

Factors within the everyday environment, such as nutrition, housing and socioeconomic status, have been found to influence development. For example, the adequacy of nutrients in the diet influences how physiological needs are met, and subsequent growth and development. When a diet is lacking in adequate nutrients, deficits in height, weight and developmental progression occur (Clinical Interest Box 15.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 15.1 Vitamin D deficiency

In some ways, Leon Jordan is a pretty typical teenager — he doesn’t get much outdoor exercise, prefers movies and video games and won’t drink milk. These habits contributed to a vitamin D deficiency that may have helped weaken the 15-year-old’s bones and leave him prone to fractures. Doctors say it’s an often overlooked problem that may affect millions of adolescents. Often undetected and untreated, vitamin D deficiency puts them at risk for stunted growth and debilitating osteoporosis later in life. While too much sunlight is bad, ultraviolet rays also interact with chemicals in the skin to produce vitamin D and it is recommended that young people spend about 10 minutes a few times a week in the sun without sunscreen because it can block the absorption of ultraviolet rays.

NURSING IMPLICATIONS

Nursing care of infants and children is directed towards promoting the optimal level of health for each individual. Care involves preventing disease and injury, promoting family involvement in child care, health teaching, participating in a team approach to care and implementing measures to meet the physical, emotional, social and cultural needs of each individual. Development encompasses various aspects, such as motor skills, vision and hearing, speech and language, intellect, emotions, personality, morals and social skills. (For facts about childhood obesity see Clinical Interest Box 15.2.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 15.2 Childhood obesity

Facts about childhood obesity

Although there is an orderly pattern to the processes, the rate of growth and development varies among individuals. Growth and development are influenced by heredity, environment, physical care, mental stimulation, personal potential and emotional security (Cameron 2002). (The characteristic stages of development in children are listed in Tables 15.1–15.3.)

PAEDIATRIC CARE

The term paediatric means of or pertaining to a child, and paediatric nursing is the area of nursing concerned with the care of infants and children. Paediatric nursing requires knowledge of normal growth and development as well as knowledge of the needs and health problems of individuals in these age groups.

The role of a paediatric nurse can be described as that of carer, coordinator, educator and emotional support and resource person. The nurse who is involved in paediatric care, together with other members of the paediatric team, needs to adopt a holistic attitude towards caring for the child and parent(s) as a family unit. Many health care facilities recognise the need for family-centred care and adopt a philosophy to meet the needs of the family as a unit.

It is important for the nurse to recognise that children are not small adults, and that their reactions are generally quite different from the adults’ reactions to illness, treatment, separation from family and admission to hospital.

CHILD HEALTH SERVICES

There are a variety of child health services whose broad aims are promoting the health of infants and children, providing parental support and care for the child who is ill. Many of the services are involved in preventing ill-health and are concerned with monitoring the health of children from birth. Preventive services include child health clinics and school health services.

Child health clinics play an important role in assessing growth and development — health education; screening for physical, metabolic and neuropsychiatric disorders; and providing immunisation against infectious diseases. The child health nurse aims to develop a close relationship with the mother and newborn infant as soon as possible after the birth. Advice is provided on infant hygiene, nutrition, growth and development, and preventive health measures such as recommended immunisation schedules. The nurse counsels and supports parents, consults with a paediatrician on health problems, refers children and families for supportive care as appropriate and keeps comprehensive records. These records include information on the child’s growth and development, immunisations and illnesses and are important tools for assessment and for detecting situations that require early intervention and preventive action.

School health services aim to promote health by providing health education programs, by ensuring that each child is as healthy as possible so that each may obtain the maximal benefit from educational programs; and by assisting in detecting and managing children with impairments, disabilities or learning difficulties. School health services perform routine medical services just before or soon after children enter school, and selective medical examinations during school life. The school nurse plays an important role in preventing and detecting illness and disabilities. Two of the tests performed on all children assess acuity of sight and hearing.

Child guidance clinics staffed by educational psychologists, social workers and psychiatrists are available to assess children and provide services to help children overcome any difficulties. The services assist children who show evidence of emotional instability or psychological disturbance to attain personal, social or educational readjustment.

Children with mental or physical impairments are provided for by health, education and social services. Integration in ordinary schools is promoted so that all children can receive education, irrespective of the degree of their disability. In some instances this may not be possible and it may be necessary to provide education at home or in a special school. Every effort is made to ensure that a mentally or physically impaired child can develop to their fullest potential.

NEEDS OF INFANTS AND CHILDREN

The needs of children throughout the various stages of development are both physical and psychosocial. Physical needs include the need for food, water, oxygen, elimination, warmth, safety and protection. Further information regarding the nutritional needs of children at various stages of development can be found in Chapter 31. Meal times in a hospital should be pleasant unhurried occasions and the environment should be one that enables children to enjoy meals. Psychosocial needs include the need for love and affection, security, dependence and independence, and self-development. When physical or psychosocial needs are not met, children experience disruptions to their biological, emotional, social or educational growth and development. When needs are not met there are a variety of effects on the child, such as a greater incidence of disease and accidents, failure to thrive, behavioural problems, delayed language skills, antisocial behaviour such as conflicts with the law or substance use and abuse, learning difficulties and social inadequacy.

SUMMARY

Growth and development are processes that begin at conception and continue throughout each stage of the life cycle. Growth may be defined as the physical changes that occur in a steady and orderly manner, while development relates to changes in psychological and social functioning. The stages of growth and development are generally described as being prenatal, infancy, childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Characteristic changes occur at each stage, but the pace and behaviours of growth and development vary with each individual.

To care for individuals from infancy to late childhood the nurse first requires knowledge of normal growth and development. Infancy and childhood are unique phases of development accompanied by special needs. The nurse who is working with children or adolescents needs to develop certain skills to provide a high quality of care.

During the 38 weeks after human conception, amazing growth and development occurs. Growth is referred to as the increase in number and size of cells of an organism as it increases in both length and weight. In the biological context, development is the manner in which cells differentiate into tissues and systems that perform a specific purpose. This chapter covers the intricate experiences that occur from conception through to birth and looks at the expected developmental growth of a young child.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Bobak I, Jensen M. Maternity and Gynecological Care. The Nurse and the Family. St Louis: Mosby, 1993.

Bolander VB. Sorensen and Luckmann’s Basic Nursing: A Psychophysiologic Approach. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994.

Cameron N. Human Growth and Development. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 2002.

Carel H. Life and Death in Freud and Heidegger. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006.

Crisp J, Taylor C, editors. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 2nd edn., Sydney: Elsevier Australia, 2005.

Hockenberry M, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML, editors. Wong’s Essentials of Paediatric Nursing, 7th edn., St Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Huitt W, Hummel J. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development. Valdosta, GA: Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University, 2003.

Leifer G. Introduction to Maternity & Pediatric Nursing, 5th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

Marieb EN. Human Anatomy & Physiology, 6th edn. San Francisco: Pearson, 2004.

Mitchell P, Ziegler F. Fundamentals of Development: the Psychology of Childhood. East Sussex: Psychology Press, 2007.

NSW Department of Health. Childhood Obesity NSW. Online. Available: www.health.nsw.gov.au/obesity/adult/about.html, 2006. [accessed 9 May 2008]

Pilliteri A. Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2003.

Sanson A. Children’s Health and Development. New research directions for Australia. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2003.

Santrock J. Child Development. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

Sherblom Matteson P. Women’s Health During the Childbearing Years. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

Sigelman CK. An Introduction to Theories of Personalities. Mahwah, NJ: L Erlbaum Associates, 2003.

Sugarman L. Life-Span Development: Frameworks, Accounts, and Strategies. Sussex: Psychology Press, 2001.

Thibodeau GA, Patton KT. Structure and Function of the Body, 12th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2004.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree