Chapter 16 Theoretical frameworks for midwifery practice

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To explain the origin of the term ‘cultural safety’ and the development of this theory

2. To describe the principles of cultural safety

3. To describe the difference between caring for a woman as the midwifery ‘expert’ and working with a woman as an equal partner

4. To explain the principles of midwifery partnership

5. To describe the concept of cultural competence

6. To discuss the implications of midwifery partnership, cultural safety and cultural competence for professionalism

Finally, this chapter examines the concept of ‘cultural competence’. A culturally competent midwife draws on both cultural safety and midwifery partnership to recognise that for each individual various aspects of culture always exist side by side and at any time one aspect may be more important than another. Through the development of skills to better understand others’ cultures and through recognition of the impact that one’s own culture has on one’s interactions, the culturally competent midwife will be able to work effectively with women with different cultural beliefs and thereby achieve better health outcomes. In order to better understand the cultural values of some Māori women, this chapter briefly outlines Tūranga Kaupapa; a set of statements about the cultural values of Māori in relation to childbirth. The underlying principles of these value statements can also be applied to women other than Māori.

MIDWIFERY AND RELATIONSHIPS

Universally, midwives understand that their role is to support and enhance this physiological and cultural process by being alongside a woman and her family as a companion or guardian (kaitiaki), using specific expertise and knowledge to ensure a safe transition to new motherhood that meets the individual needs of each woman and family (Donley 1986). This midwifery expertise is as much about knowing when not to interfere in the physiological process of pregnancy and birth as it is about recognising when and how to intervene in a way that will facilitate and enhance the woman’s ability to give birth or to confidently mother her new baby.

While midwives in Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere lost this role during the 20th century through the hospitalisation and medicalisation of childbirth, they are now reclaiming it. In New Zealand, and increasingly in Australia, midwives work in contexts that enable them to provide continuity of midwifery care throughout the entire childbirth process from pregnancy, through labour and birth, to the completion of the postnatal period at six weeks. Working with women over this nine- to ten-month period enables women and midwives to really get to know each other in a way that is much more intimate and personal than was the case when women arrived in the maternity unit to be cared for by midwives with whom they had no prior relationship. Internationally, midwives are now exploring and claiming a more personal relationship with each childbearing woman that is based on mutual respect, shared understanding and trust, and which breaks down power inequalities previously inherent in healthcare professional/patient relationships in favour of one that is negotiated and equitable (Kirkham 2000a; Page & McCandlish 2006; Powell Kennedy 2004).

Theoretical frameworks for practice

Cultural safety and midwifery partnership both also have a political imperative. Cultural safety challenges any personal, professional, institutional and social issues and structure that ‘diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and wellbeing of an individual’ (NCNZ 2002, p 7). Midwifery partnership challenges professional power structures and medical dominance over childbirth, through recognising childbearing women as active partners of equal status in the shared experience of maternity care (Guilliland & Pairman 1995).

WHAT IS A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK?

Rosamund Bryar (1995) contends that the essence of the art of midwifery is intuition and empathy that is informed by theory, knowledge and reflective thinking. Exercising the art of midwifery requires combining the personal qualities of the midwife with reflective thinking about how theory and knowledge can best be used in the care of individual women. ‘Theory provides a structure within which midwives can compare the present experiences of the woman they are caring for with the responses identified in the theory’ (Bryar 1995, p 5).

Theory arises from midwifery practice and from a range of other disciplines. The thinking of midwives about this theory in relation to their daily practice with women will lead to further development of practice theories. Theory is an integrated set of defined concepts and statements that presents a view of a phenomenon and can be used to describe, explain, predict and/or control that phenomenon (Burn & Grove 1995).

The relationship between concepts can sometimes be presented diagrammatically to illustrate how the author visualises the links between the concepts. It can also be presented through language that explains the relationship between concepts. Models and theories are ‘mental constructs or images developed to provide greater understanding of events in the physical, psychological or social worlds … and are intended to be tested, modified or abandoned in the light of new evidence’ (Bryar 1995, p 40). Theoretical frameworks are tools for making sense of and explaining reality, and for thinking about practice. They provide ways in which midwifery care may be examined, understood, tested and developed.

THE ORIGINS OF CULTURAL SAFETY AND MIDWIFERY PARTNERSHIP

Cultural safety and midwifery partnership were both developed in New Zealand and both arose out of its unique historical, cultural and social context. New Zealand’s constitutional and legislative structure is founded on the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between Māori (New Zealand’s Indigenous peoples) and the British Crown. The Treaty of Waitangi articulates a particular relationship between Māori and generations of settlers who have come to New Zealand since the early 1800s. This relationship is a bicultural partnership between Māori and the Crown that recognises the unique place and status of the Indigenous people and assures the place of both Māori and the colonists in New Zealand (Ramsden 1990, 2002).

New Zealand women drew on this cultural understanding of partnership when they actively sought changes to the way in which maternity services were delivered, and in particular demanded the choice of a midwife as their caregiver for childbirth (Dobbie 1990; Strid 1987). In the mid 1980s, maternity consumer organisations joined with midwifery’s professional organisation (at that time the Midwives Section of the New Zealand Nurses Association, now the New Zealand College of Midwives) in an organised political campaign to reinstate midwifery autonomy and enable women to have a choice of caregiver for childbirth (Donley 1989; Guilliland 1989). The campaign took place in a context in which women’s issues were high on the political agenda and the Cartwright Inquiry1 had raised awareness of patients’ rights and issues of informed consent (Guilliland & Pairman 1995). Together, women and midwives succeeded in bringing about legislative change, and the resulting 1990 amendment to the Nurses Act 1977 reinstated midwives as practitioners in their own right and gave women the choice of a doctor or a midwife, or both, as their lead caregiver for childbirth.

Another result of this political campaign was midwifery’s recognition of its political partnership with women and its determination to enact this partnership by establishing representation for women (as maternity service consumers) at every level of midwifery’s professional structure through, the New Zealand College of Midwives (NZCOM). It was then only a short step for midwives to understand that their individual relationships with women were also partnerships, or could be. Exploration of the political and professional relationships between midwives and women has led the NZCOM to identify partnership as a philosophical stance, a standard for practice and an ethical principle (NZCOM 2008).

New Zealand midwifery is redefining midwifery professionalism to mean midwifery partnership as it seeks to replace traditional hierarchical professional relationships with relationships that are negotiated and in which power differentials are acknowledged and actively shifted from the midwife to the childbearing woman so that she can control her own birthing experience (Guilliland & Pairman 1995 Pairman 2005).

New Zealand midwifery has also embraced cultural safety as developed by Irihapeti Ramsden and required of all New Zealand nurses and midwives by the Nursing Council of New Zealand (since 2003 replaced for midwives by the Midwifery Council of New Zealand) in its competencies for entry to the registers of nurses and midwives (NCNZ 2002; Ramsden 2002). The NZCOM Standards for Midwifery Practice require midwives to be ‘culturally safe’ and the Midwifery Council of New Zealand’s Competencies for Entry to the Register of Midwives require that the midwife ‘applies the principles of cultural safety to the midwifery partnership’ (NZCOM 2008, p 15; MCNZ 2004a).

All healthcare professionals in New Zealand are required by the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 to be culturally competent (see Chs 12 & 13), but cultural competence is not defined in the Act. The Midwifery Council of New Zealand considers that a culturally competent midwife integrates both midwifery partnership and cultural safety into her practice. We will explore the concept of cultural competence later in this chapter.

CULTURAL SAFETY AND MIDWIFERY PARTNERSHIP IN OTHER CONTEXTS

In all contexts, midwifery must be concerned with relationships because, unlike any other healthcare professional, midwives are privileged to have the opportunity to be ‘with’ women throughout the life experiences of pregnancy, birth and new motherhood. In their professional roles, midwives are able to develop relationships with women that last up to 10 months (sometimes longer) and they have the opportunity to work with women in their own homes and communities, away from the influence and control of institutions. In such settings the traditional practitioner/patient relationship, where the practitioner is the ‘expert’ and has the authority to make decisions, is clearly inappropriate (see Ch 12). Midwives who work within continuity-of-care models work in contexts in which relationships are valued and where midwifery attributes such as support, caring and enabling are recognised as skilled midwifery practice. Midwives and childbearing women in these settings need to develop relationships of equity, trust and mutual understanding. So too do midwives and women working within the constraints of hospital services with fragmented care, insufficient staffing numbers, hierarchies and organisational control. Such settings can undermine midwifery knowledge and midwifery confidence and trust, making it difficult for midwives to support women in taking control of their own birthing experiences (Kirkham 2000a). Both midwives and women need to take hold of their power in order to begin to change the culture of these institutions. The political partnership of women and midwives experienced in New Zealand offers some guidance (Guilliland & Pairman 1995 Kirkham 2000b).

No matter what the context, midwives should examine their relationships with childbearing women because these relationships are at the heart of midwifery practice. When New Zealand women fought for midwifery autonomy they did so because they believed that midwives would provide an alternative model to medicine—a model of care in which women would be in control as the decision-makers (Strid 1987). These same arguments are being made by Australian women and midwives seeking to strengthen midwifery autonomy through legislative and practice changes (Australian College of Midwives 2009; Maternity Coalition 2002, 2009).

CULTURAL SAFETY

Cultural safety is defined as:

The effective nursing2 or midwifery practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socio-economic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability.

The nurse or midwife delivering the nursing or midwifery service will have undertaken a process of reflection on his or her own cultural identity and will recognise the impact that his or her personal culture has on his or her professional practice. Unsafe cultural practice comprises any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual. (NCNZ 2002, p 7)

Intrinsic to the concept and practice of cultural safety is the notion of ‘right relationship’. Whether that relationship is between two persons, two groups, two cultures or two countries, right relationship recognises and honours the rights and responsibilities of each (McAras-Couper 2005). Cultural safety seeks to establish the practice of right relationship at a personal, professional and institutional level.

What is meant by ‘culture’?

… we learn from the experiences of the past to correct the understanding of the present and create a future which can be justly shared (Ramsden 2002, p 182).

Historically, in New Zealand and elsewhere, culture was invisible in nursing and midwifery curricula. In part this reflected a context in which assimilation was prevalent. Despite the existence of the Treaty of Waitangi, assimilation policy influenced the social thinking of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and led to the establishment of structures and processes that denied differences between Māori and Pākehā (non-Māori) in an attempt to make Māori more like Pākehā and absorb them into Pākehā-dominated culture and society (Walker 1987).

In this context, nurses and midwives were encouraged to give care to patients ‘irrespective of differences such as nationality, culture, creed, colour, age, sex, political or religious belief or social status’ (Ramsden 1990, p 79). This understanding of culture informed the practice of nurses in New Zealand until the early 1970s. It was well intentioned but served only to reinforce assimilation (Spence 2001). The long-term consequences of assimilation are suppression and destruction of the culture of Indigenous people, which results in mental, physical and spiritual stress (NCNZ 1992). This stress is seen only too readily in the present-day health statistics of Indigenous peoples in New Zealand and Australia and throughout the world.

In the 1970s a new understanding of culture developed. In New Zealand, as elsewhere, anthropological understandings of culture emerged which led to greater cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity. Transcultural nursing theory, developed by nurse theorist Madeline Leininger in the early 1970s, influenced nursing education. Transcultural nursing was based on nurses having knowledge about a range of different cultures from which they could respond therapeutically to their clients’ needs (Papps 2005). Nurses and midwives were taught to gather information about the beliefs, patterns and behaviours of other cultures, so that they would be able to identify ‘specific cultural patterns that occurred’ and provide culturally sensitive care (Richardson 2000, p 32; Spence 1999). Nurses and midwives were taught about the concepts of cultural awareness (becoming aware of difference) and cultural sensitivity (sensitivity to the legitimacy of difference and the impact the midwife’s own culture may have on others) (NCNZ 2002). Nursing and midwifery knowledge considered culture and race from the perspective of the nurse or midwife, as an observer, exploring and understanding what makes the other person different from themselves (Ramsden 2000; Richardson 2000). Such approaches allowed the nurse or midwife to be patronising and powerful as they identified the needs of people from other ethnic groups, and did not require any self-knowledge or change in attitude (Ramsden 2000). In New Zealand, the dominance of transcultural nursing in nursing education and practice was challenged by the alternative theory of cultural safety.

Developed in the 1980s by Māori nurse educator, Irihapeti Ramsden, cultural safety or kawa whakaruruhau provided another theoretical framework for understanding culture. This sociopolitical definition of culture had the Treaty of Waitangi as its starting point, and involved recognition that power needed to be shared and racism de-institutionalised (Spence 1999). Cultural safety focused on the sociopolitical factors that affected healthcare (Richardson 2000).

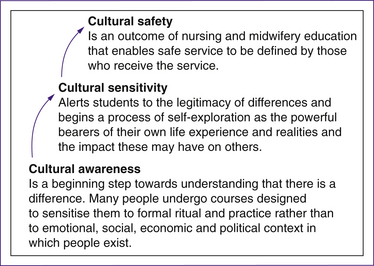

By contrast, notions of cultural sensitivity and cultural awareness avoided the more difficult recognition of power relationships that existed in the delivery of healthcare and led to cultural stereotypes and simplistic notions such as cultural checklists (Ramsden 2000). Cultural safety focused not on the ‘other’ but on the nurse and midwife. The process of cultural safety began with self-reflection and attitude change (see Fig 16.1). This process required the nurse or midwife to recognise themselves as ‘powerful bearers of their own life experience and realities and the impact this may have on others’ (Ramsden 2000, p 117).

The notion of power is inherent in the concept of and processes associated with cultural safety. The nurse or midwife is challenged to recognise her or personal power and the power of the institutions and society in which they work and live (Richardson 2000). Cultural safety is primarily about establishing trust, gaining a shared meaning of vulnerability and power, and carefully working through the legitimacy of difference (Ramsden 2000). Cultural safety makes visible the invisible structures of power (including our own), and attempts to transform anything that creates inequality and inequities in the healthcare services. In the New Zealand context this also includes actions that do not uphold the Treaty of Waitangi in the delivery of healthcare services.

Figure 16.1 describes the progression of students towards understanding cultural safety and the difference in meaning of the commonly used terms ‘cultural safety’, ‘cultural sensivity’ and ‘cultural awareness’.

Thus cultural safety and transcultural nursing present different theoretical understandings of culture. Transcultural nursing exists in a multicultural context and focuses primarily on defining culture as race and ethnicity (Ramsden 2002). Transcultural nursing places the nurse or midwife in the position of ‘external observer’ for the purpose of providing culture-specific care. On the other hand, cultural safety addresses the issue of power between the client (woman) and the nurse (midwife) and interprets ‘culture’ in the broadest possible sense (Ramsden 2002).

The development of cultural safety

Irihāpeti Ramsden’s theory of cultural safety arose from her experiences in the late 1980s in teaching student nurses, and her attempts to include Māori health issues and the Treaty of Waitangi in her teaching (Ramsden 2005). Her frustrations in trying to teach about difference and racism in a context of assimilation, where culture was seen only as ethnicity, led her to develop strategies for teaching about Māori health issues in nursing. These strategies were articulated in her framework, ‘A Model for Negotiated and Equal Partnership’, which was adopted by all schools of nursing soon after (Ramsden 1989).

In 1988, Irihāpeti Ramsden was commissioned to run a national hui (meeting), the Hui Waimanawa, which involved over 100 participants including Māori nursing students. According to Irihāpeti, it was a first-year nursing student at that hui who first coined the term ‘cultural safety’ and permitted Irihāpeti to use the term in her subsequent work. The student stood at the hui and spoke about the expectation of legal safety, ethical safety, safe clinical practice and safe knowledge bases for nurses and asked, ‘What about cultural safety?’ (Ramsden 2005, p 17). Irihāpeti Ramsden published her document, ‘Kawa Whakaruruhau: Cultural Safety in Nursing Education in Aotearoa’ in 1990. The Nursing Council of New Zealand accepted it, along with ‘A Model for Equal and Negotiated Partnership’, thus legitimising the term ‘cultural safety’ in nursing and midwifery language (Ramsden 2005).

Cultural safety required appropriate healthcare services to be provided for all New Zealanders. However, the need to address Māori health as a result of the enduring effects of colonisation had become urgent (Spence 2004). Therefore, much of the early work around cultural safety was concerned first and foremost with trying to identify ways in which healthcare services could address the poor health status of Māori (Ramsden 2002). While colonisation was primarily the reason for the poor health status of Māori, it was also the reason for the development of cultural safety, and the initial processes of teaching cultural safety needed to deal with colonial history. Therefore cultural safety teaching included analysis of the historical, political, social and economic realities that were affecting Māori health (Ramsden 2002). Nursing and midwifery students needed a ‘profound understanding of the history and social function of racism and the process of colonization’ to become culturally safe practitioners (Ramsden 2002, p 180).

In 1991, the Nursing Council commissioned Irihapeti Ramsden to write guidelines that would assist schools of nursing (and midwifery) to incorporate cultural safety (kawa whakaruruhau) into the education curricula (Papps 2002). In the council’s view it was important that such guidelines would provide a process through which students would understand difference and dominance and so ‘demonstrate flexibility in their relationships with people who are different from themselves’ (NCNZ 2002, p 12).

• to examine their own realities and the attitudes they bring to each new person they encounter in their practice;

• to be open-minded and flexible in their attitudes toward people who are different to them and to whom they offer or deliver service;

• not to blame the victims of historical and social processes for their current plight. (NCNZ 1992, p 1)

The effective nursing of a person/family from another culture by a nurse who has undertaken a process of reflection on [her] own cultural identity and recognises the impact of the nurse’s culture on [her] own nursing practice. Unsafe cultural practice is any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual, (NCNZ 1992, p 1, glossary)

• the nurse and midwife to acquire insight and analysis of themselves as cultural safety shifted the focus from other to self (Ramsden 2000)

• attitudinal change through reflection on self (Ramsden 2000)

• that clients be cared for regardful, not regardless, of all that makes them unique (Ramsden 2002)

• that the nurse and midwife understand that the care they provide is defined as safe by those who use their service (Ramsden 2002)

• that at the end of the educational process the ‘most vulnerable in our society’ can say that the nurse/midwife was safe (Ramsden 2000, p 5).

Unfortunately, few nurse educators had the educational preparation to teach cultural safety or to understand that culture was an important influence on people’s health, and students were not provided with clear definitions of culture. Where culture was equated with ethnicity, students were often taught Māori language, songs and dance instead of learning about their own cultural identity and its impact on their nursing or midwifery practice (Papps 2005).

The confusion continued in media reports that condemned the teaching of cultural safety in nursing, claiming that attention to this aspect of the curriculum was to the detriment of other more important areas such as ‘medical’ knowledge. Papps suggests that opposition to and confusion about cultural safety arose because it aims to do two separate but interrelated things. First it aims to address nurses’ and midwives’ conscious or unconscious attitudes towards any cultural differences, and second, it aims to raise awareness about imbalances in the health status of Māori (Papps 2002). Because it teaches about the effects of colonisation on the health of Māori, cultural safety has been misunderstood as being about only one culture (Papps 2002). What was not understood was that cultural safety is about addressing power relationships between nurses or midwives and the recipients of their care. Where historically nurses were taught to provide care irrespective of colour or creed and to treat everyone the same, cultural safety requires nurses and midwives to be ‘respective of the nationality of human beings, the culture of human beings, the age, the sex, the political and the religious beliefs of other members of the human race’ (Ramsden 2005, p 7). Rather than the nurse or midwife deciding what is culturally safe, it is the patients or clients who determine whether they feel safe with the care they have received (Ramsden 1995, cited in Papps 2002).

Intense political and media scrutiny of cultural safety eventually led to an investigation by a Parliamentary Select Committee in 1995. Cultural safety was ‘depicted as politically inspired while the curriculum of clinical nursing practice was apolitical and neutral’ (Papps 2005, p 26). Several recommendations from this inquiry were actioned by the Nursing Council, but it remained firm that the name ‘cultural safety’ would not change and that the Treaty of Waitangi would remain as the basis for nursing and midwifery education (Papps 2005).

In 1996, the Nursing Council published new guidelines in which the definition of cultural safety was broadened and focused less on Māori issues such as structural, political or social causes of the poor health status of Māori (Ramsden 2002). It emphasised relationships between nurses and midwives and clients who differ from them by age, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religious or spiritual belief and disability (NCNZ 1996). The council recognised that while cultural safety originated from the experience of Māori, its principles needed to be broad-based and apply to all people. ‘Culture, in the cultural safety sense, includes all people who differ from the cultures of nursing and midwifery’ (NCNZ 1996, p 8).

By 1996, the Nursing Council definition of cultural safety had evolved to include the consumer in determining ‘effective nursing or midwifery care’ (NCNZ 1996, p 9). The council said:

Cultural safety is the experience of the recipient of care. Cultural safety is well beyond cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity. It gives people the power to comment on care leading to reinforcement of positive experiences. It also enables them to be involved in changes in any service experienced as negative. (NCNZ 1996, p 10)

Ramsden (2000) argued that this all-inclusive definition of cultural safety meant that there was a need for a new curriculum design. She believed it was time for a stand-alone course in Māori health, so that the integration of cultural safety in its broadest sense could occur without threat to the issues of Māori health and the Treaty of Waitangi (Ramsden 2000).

Guidelines released by the Nursing Council in 2002 made this distinction. Cultural safety teaching was separated from teaching of the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori health in order to avoid confusion about the nature of cultural safety (NCNZ 2002). Nursing and midwifery education is now expected to prepare nurses and midwives to face and deal with personal, professional, institutional and social issues that affect the provision of safe midwifery care to women and their families.

It was Ramsden’s view that future evolution and direction for cultural safety would not focus on the customs, habits and cultural practices of any group, but rather would continue to be about an analysis of power and relationships of power (Ramsden 2002). Cultural safety is simply an instrument that allows the woman and her family to judge whether the health service and delivery of healthcare is safe for them (Kruske et al 2006; Ramsden 2002). Therefore, the next step in this journey of cultural safety will need to be centred on the facilitation of a process whereby women and their families can tell midwives about the safety of the care they receive (Ramsden 2002). This next step will facilitate the focusing of cultural safety not just on ‘ethnicity’, but increasingly will ‘promote the uniqueness of each person resulting from multiple intersecting cultural layers’ (Clear 2008, p 4).

A MIDWIFE’S STORY

Questions

1. Describe the culturally unsafe issues in this story.

2. Identify the principle/s of cultural safety that inform the midwife’s practice.

3. Describe how the midwife facilitated cultural safety in this difficult situation.

4. The student midwife states, ‘I felt so angry and upset with this I had to excuse myself and go and have a cup of coffee.’ What made the student midwife angry?

5. Discuss other ways you could navigate this situation in order to ensure the cultural safety of the woman and her family.

6. Describe how you would have handled this situation, in order to ensure the cultural safety of the woman and her family.

Principles of cultural safety

Cultural safety is facilitated by communication, understanding the diversity in worldviews, and understanding the impact of colonisation (NCNZ 2002).

There are four principles of cultural safety:

• Cultural safety seeks to improve the health status of all people.

• Cultural safety seeks to enhance the delivery of healthcare and disability services through a culturally safe workforce.

• Cultural safety is broad-based and broad in its application.

• Cultural safety focuses closely on ‘understanding of self, the rights of others and the legitimacy of difference’ (Ramsden 2002, p 200; NCNZ 2002).

Both nursing and midwifery education programs in New Zealand are based on these principles, in order to develop nursing and midwifery workforces that practise in a culturally safe way as defined by recipients of the care. Cultural safety education expects nursing and midwifery students to have:

• examined their own realities and attitudes that they bring to practice

• assessed how historical, political and social processes have affected people’s health

• demonstrated and continue to ‘demonstrate flexibility in their relationship with people who are different from themselves’ (NCNZ 2002, p 12).

In her doctoral thesis, titled ‘Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu’, Irihapeti Ramsden (2002) makes a number of statements that may also be interpreted as principles of cultural safety:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree