Chapter 9. The third stage of labour

Introduction

Sometimes the art and science of midwifery combine to confuse and frustrate the novice midwife trying to get to grips with how things should be done. A student might think that there must surely be a ‘best way’ to manage a particular situation, so why don’t all midwives practise in the same manner? Individual midwifery practice is influenced by many factors, including personal philosophy, previous experience, mentorship, delivery suite culture and, of course, hospital and national guidelines. Practice should be adapted to meet the needs of each woman who is cared for. Management of the third stage is one aspect of midwifery that is open to differing practice. This chapter aims to present the different perspectives, explore the evidence and outline safe practice.

Definition: third stage of labour

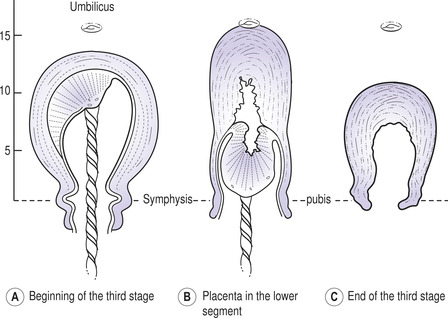

This is the interval from the birth of the baby to the complete expulsion of the placenta and membranes (NICE 2007). The process can be seen schematically in Fig. 9.1. Large studies (Combs & Laros 1991, Dombrowski et al 1995) have shown that as the length of third stage increases, particularly if it exceeds 30 minutes, the risk of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) also rises. It follows that by reducing the length of the third stage, the amount of blood loss associated with this stage of labour is reduced. Thus, most labour wards employ a policy that requires midwives to manage actively the third stage of labour. The length of this period is accurately timed and documented in the woman’s notes.

|

| Fig. 9.1 Position of the uterus before and after placental separation. (From Johnson & Taylor 2006, with permission.) |

Terminology

Active management of third stage in the UK involves the administration of an oxytocic drug to the woman after the birth of the baby’s shoulder (to ensure that shoulder dystocia is not a possibility). The cord is clamped and cut when the baby is born. The placenta is delivered by controlled cord traction (CCT).

Physiological (natural or expectant) third-stage care requires the attendant to be patient and wait for the woman’s body to do what it was designed to do. No oxytocics are given and the cord is not cut until either it stops pulsating or until after the placenta is expelled. The placenta is expelled by maternal effort.

Active versus physiological care during third stage

In 1988, the Bristol third stage trial (Prendiville et al 1988) reported that active management of the third stage of labour significantly reduced the incidence of PPH. It had set out to determine whether the routine policy of active management of labour was justified, and concluded that it was, based on the high rate of PPH in the physiological group. Indeed, the study had been stopped early by the trial’s data monitoring committee because early analysis had highlighted the PPH issue. Despite the fact that the midwives involved in the trial had received training in the physiological management of third stage, this had not been their customary practice and thus was one of the study’s weaknesses. They concluded that a randomized controlled trial should be conducted in a setting in which physiological management was the norm.

The views of women and midwives who took part in the Bristol trial were also collated and analysed (Harding et al 1989). The authors concluded that their views concurred with the findings from the main trial, and that active management was generally favoured above expectant care.

Another large trial was subsequently undertaken at Hinchingbrooke Hospital in Cambridgeshire, where midwives were already familiar with both active and expectant management of third stage (Rogers et al 1998). Again, it was concluded that the rate of PPH was lower in the actively managed women.

Subsequently, a systematic review of the available evidence comparing active with expectant management of the third stage of labour (Prendiville et al 2000:02) concluded that, ‘Active management should be the routine management of choice for women expecting to deliver a baby by vaginal delivery in a maternity hospital.’ However, there are potential advantages to a physiological third stage.

Baby’s blood volume

When nature is left to take its course, no oxytocics are given and the cord continues to pulsate after the birth, the baby continues to receive blood from the placenta. Indeed, babies in the physiological group of the Bristol trial (Prendiville et al 1988) were on average 85g heavier than those in the active management group, having received more blood than babies in the active group. A higher mean birthweight was also a finding of the Hinchingbrooke trial (Rogers et al 1998).

If the cord is clamped and cut as part of active management, then the baby is not receiving its quota of blood. This could be particularly problematic for the premature baby. In a randomized trial involving 36 premature babies born vaginally (Kinmond et al 1993), a practice of lowering the baby 20cm below the level of the introitus for 30 seconds before the cord was clamped significantly increased the initial mean packed cell volume. None of the babies in the experimental group required a red cell transfusion. In a systematic review of the research regarding the timing of umbilical cord clamping (McDonald & Middleton 2008) it was concluded that delay of 2 to 3 minutes did not increase the risk of postpartum haemorrhage but did result in a raised iron status in the baby for up to 6 months and an increased risk of jaundice requiring phototherapy.

Informed choice?

Unfortunately, many women only become involved in a discussion about the third stage if they have requested the natural method. Of course, all midwives must gain verbal consent before giving an oxytocic, but the explanation and limited discussion often take place during labour – and this is inappropriate. An opportunity to discuss such interventions should take place antenatally, ideally in the woman’s own home with a midwife she knows. The completion of the birth plan in the National Maternity Records or locally created document can facilitate this discussion. However, women only have a real choice if their attendants are confident and willing to provide either option. Anderson (1999:11) argues that, following discussion about the relative advantages and disadvantages of both methods, ‘women should then be supported in their choice by midwives skilled in both approaches to third stage care.’ Although the NICE intrapartum care guidelines recommend active management, they also state that women at low risk of PPH who request physiological management should be ‘supported in their choice’ (NICE 2007:34). For a summary of management of third stage see Box 9.1.

Box 9.1

Summary of the management of third stage

All women

■ Antenatal discussion

■ Wishes recorded in birth plan

■ Review of birth plan in early labour

Physiological management

■ Spontaneous birth of baby

■ No prophylactic uterotonic

■ Umbilical cord left unclamped

■ Signs of placental separation

■ Placenta delivered by maternal effort

Active management

■ Birth of baby’s anterior shoulder

■ Administration of IM uterotonic, with consent

■ Uterine contraction

■ Controlled cord traction whilst guarding uterus

For some women, part of the mystery of giving birth is learning about how their bodies respond to the demands of labour and birth. They may have endeavoured to go without drugs, either to ease or speed up their labour, and would also like to do the same for third stage. Having a physiological third stage when so many women have active management can be a valuable achievement. Many women in the physiological arm of the Hinchingbrooke trial (Rogers & Wood 1999) found satisfaction in the fact that they had birthed their babies without any intervention. Alternatively, it could be the redeeming factor of an otherwise difficult experience where previous choices had to be abandoned – for example, if transferred to hospital when a home birth had been planned.

Active management

Drugs used for active management

The preparation commonly administered is 1ml Syntometrine, which includes 5 international units (IU) oxytocin and 0.5mg ergometrine maleate, both belonging to the group of medicines known as oxytocics which cause the uterus to contract. The route of choice is intramuscular, and the site is often the accessible lateral aspect of the leg (Baston et al 2009). The syntocinon component of Syntometrine works within 2 to 3 minutes and lasts only 5 to 15 minutes, whereas the ergometrine takes 6 to 7 minutes to work but has a sustained action lasting up to 2 hours (Johnson & Taylor 2006). Ergometrine can have the undesirable side-effects of nausea, vomiting, headache and raised blood pressure (Jordan 2002). If the use of ergometrine is contraindicated – for example, if the woman has hypertension – then oxytocin should be administered. When intravenous oxytocin is required, a dose of 5IU should be administered slowly by an experienced practitioner.

The NICE intrapartum care guidelines recommend the use of 10 international units (IU) of syntocinon by intramuscular injection, although it is not licensed to be given by this route (Alliance Pharmaceuticals 2007). A systematic review examining the prophylactic use of oxytocin during the third stage of labour (Cotter et al 2001) concluded that oxytocin is beneficial in the prevention of PPH. However, there was insufficient evidence regarding the side-effects of its use and to what extent they compromise its use. There was little evidence to support the use of ergometrine alone versus syntocinon alone or a combined product for preventing PPH of more than 1000ml and the authors recommend further research to evaluate their use. A subsequent review (McDonald et al 2007) found a small reduction in PPH of 500ml when a combined ergometrine–syntocinon product was used, but again no difference between groups for blood loss of more than 1000ml. The authors concluded that the undesirable effects of nausea, vomiting and raised diastolic blood pressure need to be weighed againt the reduction in blood loss.

Oral misoprostol has also been used as a means of actively managing the third stage of labour. A randomized controlled trial (Oboro & Tabowei 2003), comparing oral misoprostol with intramuscular oxytocin after birth, found no significant differences between the groups regarding postpartum haemorrhage, length of third stage or the incidence of manual removal of the placenta. However, more women experienced shivering in the misoprostol group and another study (Lumbiganon et al 2002) found that misoprostol was associated with post-delivery diarrhoea.

Controlled cord traction (CCT)

If an oxytocic has been administered, then the placenta and membranes are usually delivered by CCT. This technique, when applied in the UK, generally involves the midwife awaiting signs of separation (of the placenta from the uterine wall). These include: contraction of the uterus which will change from feeling broad to becoming firm and more rounded, lengthening of the cord at the introitus and a small trickle of blood observed from the vagina. A sterile towel is placed on the woman’s abdomen, and the midwife places her still hand on the towel to await a contraction.

If right-handed, the midwife will ‘guard’ the uterus with her left hand by keeping her fingers together, opening her thumb and positioning her hand on the woman’s abdomen just above the symphysis pubis. The purpose of this action is to prevent the uterus from following the placenta and prolapsing or inverting. The midwife continues to ‘guard’ the uterus while she undertakes CCT. Firm backward counter-pressure is applied, and this position should be maintained throughout CCT (the hand only being removed after traction has stopped).

With the right hand, the midwife takes the clamped cord and wraps it around her index and middle fingers. Firm, but slow and steady, traction is used to guide the placenta into the vagina. This traction is down towards the bed or floor, depending on the woman’s position. If, as traction is applied, the midwife feels that the cord is breaking, then traction should cease and the maternal effort method should be employed.

Actively delivering the placenta and membranes

When the bulk of the placenta appears at the vulva, the direction of traction is changed to a horizontal then upward movement. When the whole placenta is visible, the midwife cups it in her hands and slowly rotates it in a clockwise direction, thus twisting the membranes that follow it into a rope. This action is undertaken with the aim of keeping the membranes together in a form that can conveniently be grasped with forceps if they are reluctant to escape from the uterus. The delivery of this rope of membranes can be assisted by slowly lifting the cupped placenta up then down and up again. This action is repeated until the membranes are completely expelled. The placenta and membranes are placed in the sterile receiver included in the birth pack, to await inspection.

Physiological management

Physiological or expectant management of third stage should only be offered if the first and second stages were also physiological, hence the balance of hormonal and psychological aspects of birth remain in equilibrium (Fry 2007). As it is often hospital policy to undertake active management of the third stage, many midwives will not be confident with this aspect of midwifery care. It is therefore rarely offered as an option when the birth plan is being discussed. However, women who request a physiological third stage should receive skilled and competent care from the midwife and it is important therefore that an understanding of the principles of physiological management are maintained to prevent this practice from becoming a ‘dying art’ (Walsh 2003).

The central principle is to observe the process – do not intervene unless the woman starts to bleed heavily or the baby needs separating from the mother for resuscitation. A small trickle of blood from the vagina is normal as the placenta separates. Physiological third stage can take up to 1 hour, although the average length of time in the Hinchingbrooke trial for physiological management was 15 minutes (Rogers & Wood 1999). Constant attention and observation must be maintained. The woman should not be left by the midwife while the placenta is still in utero.

When is physiological management of third stage contraindicated?

Find out if any of the students in your group have observed a physiological third stage.

Find out if any of your peers have conducted a physiological third stage.

Maternal effort

If the woman has not had an oxytocic, and a ‘hands-off’ approach is being taken, she can wait until she feels the placenta in her vagina and then simply push it out. An upright sitting, kneeling or squatting position will work with gravity to assist this process. If the membranes remain in the vagina, the midwife should use the twisting method described above to ensure their complete expulsion.

If maternal effort is being used because CCT had to be abandoned (because the cord was thin, weak or was felt to be shearing from the placenta), and the woman has had an oxytocic, she should be encouraged to bear down. She may find this activity a little difficult or strange after her exertions during the second stage. She may benefit from you placing a flat hand on her abdomen and asking her to push against your hand.

Delivering the placenta after caesarean birth

A range of methods for delivering the placenta following surgical birth have been practised including manual removal, spontaneous dellivery after placental drainage and cord traction. A systematic review of the research evidence (Anorlu et al 2008) concluded that cord traction results in fewer complications including less blood loss and associated reduction in haematocrit, less endometritis and shorter hospital stay.

Cutting the cord

Increasingly, parents are requesting involvement in this significant aspect of the birth of their baby. It is a request that can usually be accommodated, even if the baby is born by forceps or ventouse extraction. The obstetrician or instrumental practitioner should be made aware at the beginning of the delivery and then gently reminded as the baby is born. It is important to respect and accommodate where possible the details of the parents’ aspirations for the birth. These form part of the story that will be told for many years to come.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree