Chapter 8 The therapeutic encounter

With a holistic approach to health and disease the importance of the therapeutic encounter is paramount. During an assessment a practitioner considers the spiritual, psychological, functional, and structural aspects of a patient. They inquire about the building blocks to health, family, social, environmental, and external factors. A thorough assessment includes the current physiological and pathological state of a patient. The aim is to identify the initiating and aggravating factors that are contributing to the symptoms and illness, and to determine what needs to change or what a patient requires in order to stimulate their innate healing ability and to achieve a desired state of wellness. Subsequent visits assist with understanding how a patient is progressing on their journey to health and in identifying new patterns as they emerge.

The inquiry into the cause of symptoms and diseases and how to detect illness in the body has always been at the heart of the medical profession. The methods used for assessment have changed substantially over time, and prior to the eighteenth century, history taking and diagnosing was based on the subjective symptoms of patients (Magner 1992). As the conventional medical field introduced more objective means of assessing health and disease, the relationship between the patient and the practitioner became more distant. The information obtained by objective measures was, and often is, taken as more valuable than the subjective information conveyed by a patient. In a naturopathic and holistic assessment a practitioner must value and integrate both the subjective symptoms and the objective signs, and recognize that the patient is more important than the disease. ‘In other words, the subjective should be part of a disease, just as it is part of being ill. If we find a way to include the subjective in our concepts of disease, maybe we will also discover purpose and meaning’ (Duffin 2007).

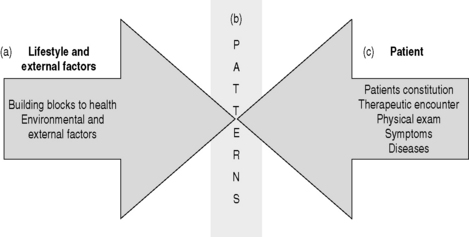

The naturopathic approach is based on the understanding that health and disease are multi-factorial and that there is a logical pattern that links the patient’s behavior and symptoms with their lifestyle, environment, and external factors (Fig. 8.1). This pattern emerges when we see all aspects of life and nature from the perspective of their qualities and attributes. During the therapeutic encounter a practitioner is looking at putting all the pieces together and determining the overall patterns for each patient. It is by treating the patterns and the patient as an integrated whole that health is achieved and maintained.

PATIENT–PRACTITIONER RELATIONSHIP

Communication, both verbal and non-verbal, is the medium through which relationships begin and develop. The quality of communication directly influences the quality of the relationship and it is strongly linked to patient adherence and satisfaction (Bernstein & Bernstein 1985, Barrier et al 2003, Platt & Gordon 2004). The primary purpose of the patient–practitioner relationship is the optimal well-being of the patient. The reason for the initial visit is for the patient to convey to the practitioner their medical history and to provide the practitioner with a window into who they are and how they live their life. The therapeutic encounter is not simply an exchange of information; it is, or can be, therapeutic in and of itself. A detailed and attentive intake often is the first time that many patients have been able to convey ‘their story’ and feel heard. The ability of a practitioner to hear the correlation between a patient’s complaints and their constitution, or situations that have happened in a patient’s life and their symptoms is a valuable skill. Occasionally, a patient might even experience extraordinary ‘spontaneous’ healings of very serious injuries or diseases when there is a strong connection between the patient and practitioner (Murphy 1993).

The patient–practitioner relationship is influenced by the beliefs of the practitioner, the time and attention that each dedicates to the relationship, by the expectations and openness of the patient, and by the encounter itself. There are many factors that come into play. A practitioner might intimidate the patient or might convey judgment in the way that they speak. A patient might be too frightened or too embarrassed to give an adequate account of symptoms, or they might be defensive about the etiology and causal factors. A patient might be uncertain what a practitioner is looking for and might narrow their responses to the point of leaving out key information, or they might not tell the exact truth about their compliance if they anticipate judgment or disappointment. Being aware of the numerous factors that impact relationships is critical to understand what is really behind what a patient is saying.

From the point of view of the patient, then, the most serious barriers to a good relationship (and consequently better diagnosis and treatment) are the professional’s lack of time, seeming lack of concern, and failure to tell the patient what the patient needs to know and can understand about the illness (Bernstein & Bernstein 1985).

Research also shows that spending time early in patient encounters saves time in the long run (Platt & Gordon 2004).

A naturopathic assessment links the symptom patterns to factors that have contributed to their onset. At times, the symbolic meaning of a single symptom ‘jumps out’; when this happens it is important to avoid treating symptomatically or treating individual findings. What a practitioner is looking for is the underlying pattern, what ties all the symptoms together. You are looking for the factor or factors that initiated and contributed to the state of overwhelm and disharmony. For example, a patient might have a swollen left ankle because of collapsed veins, inability to hold her urine, spotting with her period, and rounded shoulders. The common thread, or pattern, is a lack of earth. There isn’t enough earth for the vessels to hold in the blood or the lymphatic fluid, the bladder is lacking the strength to hold in the urine, and her structure is becoming rounded because of a lack of earth. The next step is to find out what has happened in her life to affect her earth; her sense of structure and support. For example, it could be when she lost her job all of a sudden, or when her marriage broke down, or it might be a life-long concern because she has always had a weak sense of confidence.

Role of the practitioner

A practitioner is a guide and a facilitator of health. Their role is to listen and observe from a neutral place, without judgment or preconceived ideas. They use their skills and knowledge to identify the root cause of disease, and to provide the education and support that is needed for healing. To recognize the uniqueness of patients, to identify and remove obstacles to cure, to support the inherent healing ability of each patient, to recognize the stages of disease, and to prioritize treatment recommendations to ensure optimal wellness and a logical healing process. It is to be curious about health and to remember that health and disease have a logical pattern, to continually search for the truth and the factors that are at play for each individual patient. The aim of a practitioner is to translate the patterns back to the patient in a way that provides them with the knowledge to change what needs to be changed in order to restore wellness and a homeodynamic state. ‘The most important treatment any doctor can give is to hope for the health and well being of his or her patients’ (McTaggart 2002).

The specific energetic constitution and beliefs of a practitioner also impacts their approach and style with patients. It is valuable for practitioners to understand their own constitution, to recognize how they process information, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. For example, if a practitioner has a lot of ‘earth’ qualities, that is they are good at details and like order and continuity, they are more likely to get impatient with patients that are more scattered or that tend to go and on and on when speaking.

THE HOLISTIC INTAKE

The importance of the history cannot be overestimated. Studies performed with hospital out-patients show that diagnoses are made from the history in the vast majority of patients. Examinations only provide significant unexpected findings in a minority (Welsby 2002).

Every encounter with a patient, whether the first time or follow up, involves conversation. The conversation is an integral part of the ongoing assessment process and it requires time and attention. It is through conversation that a patient can tell their story, that they can indicate the impact that their life has had on them, and their desire for change. Conducting a thorough history is not unique to naturopathic medicine. The difference is that a naturopathic practitioner typically asks a broader range of questions and asks for more details on each component of the intake. A holistic intake explores the following:

PATTERNS CONVEYED THROUGH LANGUAGE

Words and language are powerful. They can stimulate the healing process or block it. The words that patients use, and the words that practitioners use, have a direct and dramatic impact on the therapeutic encounter. Words trigger memories and they are used as a way of tracking, labeling, and categorizing our experiences.

It is of inestimable importance that we are able to listen deeply to our patient’s words and to be aware of our own. The quality of our ability to think deeply and consistently about the unconscious experience of our patient is intimately related to our ability to hear what is being said. The effect of our own words upon the patient likewise cannot be overstated (Proner 2006).

Meaning of words

The meaning of each word is complex and unique to that patient. Words are symbolic triggers that have energy and that bring into consciousness aspects of a patient’s experience (Bandler & Grinder 1979). Speech is a form of symbolic behavior and it holds meaning.

Thought processes suppose context and meaning. One cannot simply think; one has to think something. One does not simply ‘behave,’ but behavior is directed toward a conscious or unconscious goal (Thass-Theinemann 1968).

There is a difference between a patient looking to manage their pain better and having the expectation and belief that they can be pain free; or a patient expecting that it is normal to have a good night’s sleep every night, instead of just once in awhile; or a patient believing that once they have hypertension they will have it for ever. In order for a patient to change their perception and way that they interpret events in their life, they need to bring their unconscious beliefs and expectations to their consciousness (Murphy 1993). If a patient has a limiting belief about their symptoms or state of disease, it limits the degree of health that they achieve.

Verbal linking

When patients are conveying information to a practitioner they do so in a specific sequence. They link events and symptoms often unconsciously. This linking and sequencing of language is an important piece of the puzzle. It provides a guide to the factors that have contributed to the state of overwhelm and it indicates the factors that need to shift in order for healing to begin. For example, when a patient says, ‘Ever since university I have had digestive problems’, the practitioner then ask further questions to determine what changed in university, was it because of late nights, changes in dietary habits, increase in alcohol, stress because of grades, relationship issues, or something else.

Energy of words

The impact of words is especially relevant when it comes to the labeling of diseases and the conveying of the relationship between symptoms, disease, and a patient’s life. Words have energy, and there are symbolic meanings to many diseases that have an impact on a patient’s perception of their ability to heal (Benor 2006). For example, the fear associated with the diagnosis of cancer, the chronic debility associated with arthritis, the anticipation of ongoing pain associated with the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Words either create boundaries or opportunities. The words that a patient associates with their symptoms and disease convey not only the nature and characteristics of the symptoms, but the symbolic meaning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree