CHAPTER 6 The systematic review process

6.2 Introduction

6.3 The systematic review process

6.3.1 Developing the review protocol

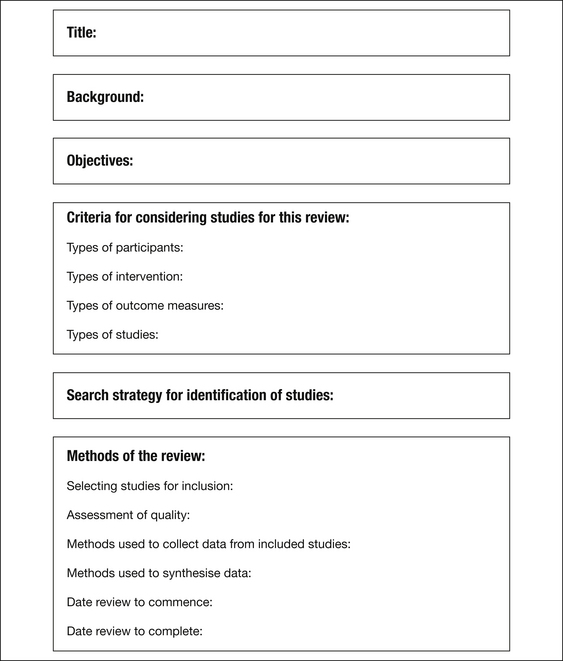

Figure 6.1 The Joanna Briggs Institute review protocol

Reproduced with the permission of the Joanna Briggs Institute

The review protocol reproduced in Figure 6.1 is that used by the JBI.

6.3.2 Asking answerable questions

Sackett et al (1997:22) argue that almost every time a medical practitioner encounters a patient they will require new information about some aspect of their diagnosis, prognosis or management. This is no less true for other health professionals. They note that there will be times when the question will be self-evident or the information will be readily accessible. This is increasingly the case as sophisticated information technology gets nearer and nearer to the bedside. Even so, there will be many occasions when neither condition prevails and there will be a need to ask an answerable question and to locate the best available external evidence. This requires considerably more time and effort than most health professionals have at their disposal and the result is that most of our information needs go unmet.

The first step is to have a question that is answerable. Asking answerable questions is not as easy as it sounds, but it is a skill that can be learned. Sackett et al (1997:30) offer some useful advice in the context of evidence-based medicine and the effectiveness of interventions. These sources can be extended beyond questions of effectiveness, to consider the appropriateness and feasibility of practices. The source of a clinical question (adapted from Sackett et al 1997) includes:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree