Common errors and omissions in the admission of elderly patients314

Introduction

Common Errors and Omissions in the Admission of Elderly Patients

Failure to obtain an adequate history

Failure to establish a correct drug history

Failure to make an adequate review of the patient’s previous hospital records

Inadequate nursing and medical assessment

Taking the History

Taking a History From the Patient

Pain

Taking a History From a Third Party

Where to go for information

Dealing with relatives

Liaising with the medical staff

Falls

The Cause of Falls

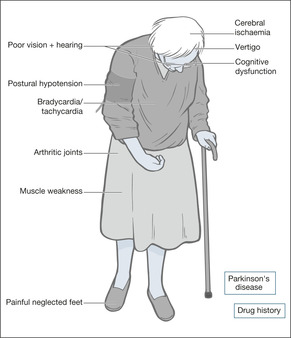

Fig. 9.1

CASE 1

CASE 2

CASE 3

Assessment After a Fall

Critical nursing tasks in assessment after a fall

Ensure the safety of the patient: ABCDE

Look for injury

Has this been a stroke?

Arrange for an urgent ECG and cardiac monitor

How to identify postural hypotension

Important nursing tasks in assessment after a fall

Obtain an adequate history

Assess mobility

Assess cognitive function

Speak to the carers and close family

Additional assessment on examination

Answering Relatives’ Questions in Patients Who Fall

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The ‘social admission’

Delirium330

Dementia338

Nursing home admissions339

Ethical issues and the elderly sick341

The emergency admission of patients with a terminal disease343

The label of ‘social admission’, while acknowledging the issue of the home circumstances, is a disservice to this group of patients, as it inevitably means that less effort is paid to establishing exact diagnoses. In fact a pure ‘social’ admission – one in which the patient is medically stable but in which the care input has failed – is a rare event and the term is generally unhelpful:

• it suggests a non-urgent or elective admission

• it denies a medical cause for admission

• it discourages a full medical assessment

• it implies a ‘social’ solution to the problems

• it suggests the patient can soon be shifted to hotel-type care

• the term falls into the same category as the unhelpful ‘bed blocker’ or even ‘off legs and unable to cope’, in which the emphasis suggests the unwelcome nature of the admission, rather than the challenge of returning an elderly person to their home with improved health

• Simple communication failure – patient too ill or too deaf to communicate

• Acute confusion/delirium

• Long-standing confusion

• Inadequate referral details, particularly from the deputising service or from a nursing home

It is important to establish:

• what the patient’s doctors have prescribed

• what the patient has actually been taking

• when any changes in medication occurred

Common problems with the drug history include:

• new treatments that do not appear on a repeat prescription list

• tablet bottles that contain a mixed assortment of drugs

• medications that the patient does not consider to be a drug

— Etidronic acid (Didronel PMO®; ‘fizzy drink’)

— monthly (e.g. B12) or weekly (e.g. methotrexate) treatments

— insulin

• non-compliance with multi-drug regimens (more than three different medications)

• failing to mention p.r.n. drugs, especially analgesics

• confusion concerning the doses of diuretics and the correct use of inhaled medication

Re-admissions in this age group are common. Hospital notes are helpful, but they can be difficult to track down. Some of the patient’s problems may have been identified already: examples include septicaemia due to known kidney stones or gallstones, recurrent angina or dizzy episodes due to arrhythmias, and falls due to alcohol abuse.

• Failure to assess the musculoskeletal system

• Missed crush fracture of the spine

• Missed fracture of the long bones

• Missed joint infection

• Missed shoulder injury following a fall

• Missed broken skin over pressure areas

• Failure to diagnose ‘silent’ myocardial infarction

• Silent pneumonia

• Silent septicaemia

• Faecal impaction as a cause of worsening confusion in a patient with dementia

• Failure to take an alcohol history (alcohol problems in the elderly present with depression, confusion and falls)

Elderly unwell patients often have considerable difficulty in recalling the time course of the symptoms that brought them into hospital. For many, the point at which new symptoms took over from the chronic symptoms of generalised ill health and multiple pathology will be far from clear. For many elderly patients the process of giving a history, often more than once when they are already feeling unwell, can be a considerable ordeal. The tendency is for staff to rush them rather than sit and listen (→Case Study 9.1).

• Every patient has his or her own life story and, with patience, you will learn more from them than they will from you

• Piece together the history and try and find something of the person rather than simply the ‘admission problem’

• In the elderly, you are more likely to encounter atypical symptoms in commonplace conditions: dizziness as a presentation of myocardial infarction; ‘off legs’ as a result of a urinary tract infection; acute confusion as a side-effect of a change in drug treatment

• It is important that efforts are not duplicated and that the patients are not subjected to unnecessary repetition

• It is critical to obtain a history from a third party: a close relative, a professional carer or from the patient’s GP

Case Study 9.1

An 84-year-old man was admitted under the chest physician with immobility due to painful feet. He was frustratingly slow to give a rambling history, but after having successful dermatological treatment to his cracked and fissured soles he slowly mobilised. He was referred for rehabilitation and seen briefly at the end of very rushed ward rounds as ‘… and just the sore-foot man waiting to go to elderly care’. On a less hectic round he mentioned that he, too, had worked in a hospital and proceeded with a detailed account to a chastened chest consultant about the 20 years he had spent nursing in one of the country’s earliest cardiothoracic surgical units, how fierce the matron was and, in his day, how precise the bed alignment had to be prior to consultant ward rounds.

It can be difficult to separate symptoms from different systems. The problem of referred pain and the inability of some elderly patients to describe and localise their pain clearly can make it challenging for the listener. Examples include band-like abdominal pain attributable to collapsed thoracic vertebrae, upper abdominal pain due to acute myocardial ischaemia with cardiac failure, and diffuse abdominal pain due to a strangulated femoral hernia. To complicate the issue, many patients have pre-existing chronic pain from joint degeneration, from poorly controlled angina and from chronic arthritis of the spine.

The patient’s description of the home circumstances and his level of dependence must be supported by evidence from other sources. Without a detailed background, the assessment is seriously flawed:

• the patients may be unforthcoming because of confusion, anxiety or depression

• carers may have a different perspective on the situation

• late information cannot contribute to the critical initial diagnostic process and will probably delay the eventual discharge

1. Relatives

2. The previous hospital medical and nursing notes

3. GP – early liaison with primary care will save a lot of time

4. Community nurse

5. Nursing home staff

6. Health visitors

7. Neighbours

8. Home care services

9. Social services

• Many relatives fear that an elderly person may be written off at an early stage and may therefore be defensive about their normal level of dependence. Just because someone is 85 years old, it is wrong to assume that either the relatives or the patient will take a philosophical view about having had a ‘good innings’. Some of the most serious allegations of substandard care concern this area. Relatives often assume that, in the chaos of an acute unit, the elderly are given lower priority.

• Be sure who you are dealing with and what input they have in the care of the patient. It is not helpful to have an early detailed discussion with a niece who happens to be on the ward, before speaking to the daughter who has been sacrificing her sanity and her marriage to look after her confused elderly father for the past 5 years.

• Be sensitive to family dynamics, particularly in the issues of chronic dependence and dementia. The admission may have been the culmination of months of severe family stress in trying to cope with an increasingly difficult situation. The elderly spouses of patients with dementia often show evidence of significant stress-induced ill health. A straightforward and tactful information-gathering exercise is all that is needed in the early stages.

Communication with the admitting doctors is of paramount importance in the management of the elderly. Apart from minimising the ordeal for the patient of repeating the same information to different staff members, there is critical information that must be shared at the outset:

• the patient’s baseline level of dependency

• the presence and time course of any confusion

• any suspicion of a head injury or a fracture

• the relatives’ main immediate concerns

• any particular risk of falling

1. Establish the depth of personal knowledge. Is the history from a third party due to personal familiarity with the patient, or is it hearsay?

2. When was the patient last well, and from that point how did the symptoms first develop, giving an approximate order?

3. What is the level of dependence and when did this change?

4. Establish the usual mental state and if there is a component of confusion/loss of short-term memory – when did it first develop, and how has it progressed or changed over time?

5. When you are doing your assessment, try to picture the patient in their own environment.

Falls are a common and important cause for acute medical admission. Almost 10% of patients aged 70 years and over will attend the Accident & Emergency Department at least once per year with injuries caused by a fall and a third of these will be admitted to hospital. Apart from a 10% risk of a fracture, falls have long-term consequences, particularly if they are recurrent:

• they lead to loss of confidence

• they are a threat to independence, particularly when they are recurrent

• hospital admission after a fall often triggers a slow general decline

In spite of their importance, patients are often not adequately assessed to establish the causes or the effects of their fall. Many will have attended on several previous occasions: a first-time faller has a greater than 50% chance of falling again within 12 months. In a significant proportion, the cause is reversible or the risk factors can be reduced.

Fig. 9.1 and the following case studies illustrate the many factors that increase the risk of falls.

Most falls are caused by a combination of internal problems with balance, vision and posture, and external factors such as loose rugs, poor lighting and cluttered living space. The fall may be triggered by new medication leading to dizziness or confusion, or the effects of an intercurrent acute illness such as anaemia, heart failure or infection. Case Studies 9.2 illustrate such falls.

Case Studies 9.2

A 90-year-old-woman was started on the antidepressant, dothiepin: one tablet in the morning and two at night. She was also already taking atenolol 100mgHg a day, beta-blocker eyedrops and bendrofluazide. She had fallen and lain against the radiator, suffering a full-thickness burn to the right shoulder. On admission, her systolic blood pressure fell by 30 mmHg when she stood up from lying, associated with unsteadiness. She was otherwise well.

• Drug treatment is a common and treatable factor in falls

• Half of all elderly fallers cannot get back on their feet unaided

An 86-year-old woman was visiting her daughter at Christmas. She tripped in her bedroom and was in the line of a fan-heater. She was unable to move and suffered extensive burns to both lower legs.

• Falls are more common in unfamiliar surroundings, particularly those encountered when staying in cluttered or poorly lit spare rooms. People become used to their own frayed carpets and unsafe stairs, but these pose a threat to an elderly guest.

An 83-year-old man was admitted having been found on the floor with extensive occipital bruising. He had signs of a chest infection, but with treatment made a good recovery. Mobilisation, however, was very slow. He had generalised stiffness, a tremor and was very reluctant to move his feet due to fear of falling. A diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease was made and he was started on treatment.

Falls are common in Parkinson’s disease:

• patients tend to topple backwards

• they are slow to correct any imbalance

• there is often an associated postural hypotension

Patients will be admitted after a fall if:

• they fail to make a full recovery

• they have injured themselves

• they are in need of care that is not available at home

• a serious medical cause for the fall is suspected

Assess the vital signs and, if the patient is acutely ill, correct oxygen saturation, exclude hypoglycaemia, examine the pulse for bradycardia or tachycardia and measure the core temperature (hypothermia or fever). Always search for postural hypotension: a fall in the systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more on standing upright (postural changes can be identified in the immobile from recordings taken when the patient sits up with the feet dependent over the side of the bed).

Pain is the main clue to injury, although acute confusion can mask pain completely. Note the sites of pain – they will need to be X-rayed if there is tenderness, deformity or swelling. Inspect the scalp for bruising, look behind the ears (Battle’s sign; →p. 106). Is there bruising around the hips? Look for pain on moving the wrists, shoulders, hips and elbows. Pleuritic pain may be due to fractured ribs. Deep pain in the lower back or groin is seen after pelvic fractures. If the patient has been lying in one position, there may be soft tissue pressure damage (bruising, discolouration and swelling) or burns.

If there is any pain around the neck or radiating round to the jaw – consider high cervical spine injuries (fractures can occur here in the elderly even with minor, low impact falls). CT of the cervical spine may be necessary.

Examine for one-sided weakness, facial droop or an obvious speech disorder. Confusion must not be confused with dysphasia. If a stroke is suspected, check the safety of the airway and of the swallow.

This is to exclude a myocardial infarction or arrhythmia as the cause of the fall.

The supine blood pressure is the value obtained after the patient has been lying quietly for 10 minutes. The standing blood pressure is the value obtained after the patient has been standing for 5 minutes. A drop in the systolic pressure of 20 or more or if the systolic pressure falls below 90 – particularly if accompanied by symptoms – indicates postural hypotension. The change in posture can also be accompanied by a marked increase in heart rate (by 30 or more bpm or to a rate > 120 bpm) which may also be associated with symptoms of dizziness and can be the culprit in some cases of syncope.

• What were the circumstances? A fall, often forwards and causing facial injury, in which there is no warning and no loss of consciousness, suggests a drop attack. A ‘draining away’, particularly on standing with greying vision and fading voices, suggests syncope. It should be remembered that the elderly may not realise that they have lost consciousness and can have significant postural hypotension in the absence of symptoms. Dizziness with the room spinning, especially if triggered by sudden turning or neck extension, suggests vertigo. If the patient has acute vertigo and cannot stand without support, and particularly if there is also slurring of the speech and focal weakness, a posterior circulation stroke is the likely cause. Head injuries, particularly in males, are frequently associated with excessive alcohol intake.

• What is the drug history? The main culprits are nitrates, diuretics and antihypertensives – all causing postural hypotension – and psychotropics, notably long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. nitrazepam), anticonvulsants and antidepressants, affecting balance and causing drowsiness.

• Establish the patient’s existing mobility and cross-check their account with that of a relative: patients often overestimate their usual level of function.

• For a more objective assessment, there are three simple tests that can be tried once the patient has recovered from the immediate effects of the fall.

1. ‘Get up and go’ – the patient who can rise from a chair, stand steadily, walk across the ward, then turn and return to the chair without help does not have an immediate problem with mobility or balance.

2. Can the patient stand on one leg for 10 s? This will give a rapid global assessment of balance, power in the lower limbs and difficulty with weight bearing due to, say, problems with arthritic knees.

3. Does the patient stop walking when he talks? Patients who are beginning to find mobility an increasing problem, for whatever reason, have to marshal their resources when dealing with the challenge of walking. This is apparent if a conversation is started while the patient is on the move – they will stop walking in order to talk.

This is an important part of any assessment in the elderly patient, but in the particular case of recurrent or unexplained falls, cognitive impairment will have a profound effect on the plans for discharge.

The AMTS (→Box 9.1) is simple to administer: a score of less than 7 out of 10, assuming this is not due to a simple communication problem, suggests cognitive impairment. The next step is to establish from the relatives’ history whether this is a recent or long-standing problem.

Box 9.1

1. How old are you now?

2. What time is it now (to the nearest hour)?

3. I will give you an address and ask you to repeat it later on: 42 West Street

4. What year is it now?

5. Can you tell me where you are now?

6. Can you tell me who (two persons) these people are?

7. Can you tell me the date of your birthday (day and month)?

8. What were the dates of the First World War?

9. Who is on the throne at present?

10. Can you count from 20 to 1 backwards?

• Obtain an overall picture of the patient in his home, with an emphasis on mobility, vision and the immediate domestic environment. Confirm the drug (and alcohol) history. Check the input from family and professional carers.

• Has there been evidence of cognitive impairment: memory loss and difficulty with complex tasks?

• Look at the feet and lower limbs. Examine for generalised arthritis, particularly of the knees. Knees that are swollen, arthritic and stiff are often associated with thigh muscles that are weak and wasted through disuse. Is there generalised weakness of the legs? Are the feet well cared for or are they misshapen, with overlapping toes, bunions, painful fissures and huge uncut nails?

• Assess the hearing and vision. Sensory deprivation leads to loss of balance, a loss of the compensatory mechanisms needed to maintain equilibrium, and a reduction in the level of self-confidence. Ensure hearing aids and glasses are brought in soon after admission.

• Evaluate and localise any pain and ensure appropriate analgesics are prescribed and given.

Why do the falls keep occurring? The majority of elderly patients who fall will fall again. However, while some risk factors cannot be corrected some, such as drug side-effects and environmental factors, can be addressed.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access