1.1 Know the lie of the land

Over the past two decades healthcare environments have become increasingly complex, technological, consumer orientated and litigious. Factors such as high patient throughput, increased acuity and decreased length of stay mean that hospitalised patients are sicker than ever before and stay in hospital for increasingly shorter periods of time. In a snapshot of a typical day in New South Wales in 2008, Garling (2008, p. 1)noted that:

• the ambulance service was responding to an emergency 000 call every 30 seconds;

• 6000 patients were arriving at emergency departments seeking treatment;

• 4900 new people were admitted as hospital in-patients;

• 17,000 people occupied a hospital bed, of whom 7480 were over 65 years old;

• 7000 separate medical procedures were performed;

• $34 million was spent on providing healthcare in public hospitals.

These figures are dynamic and changing; however, they reflect the complexity that characterizes contemporary Australian healthcare. The last two decades have also seen rapid and dramatic improvements in healthcare technologies, research, skills and knowledge. When coupled with nursing shortages and variations in skill mix these factors have made nurses’ working lives challenging, intense, exciting and sometimes stressful.

Something to think about

Something to think about

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870), A Tale of Two Cities

Why are we sharing this information with you right at the beginning of this book? Certainly not to discourage you from your chosen career path, but with the wisdom of knowing that ‘forewarned is forearmed’. You’d be foolish to travel to a foreign land without some degree of preparation in order to develop an understanding of the culture, people and context. The clinical learning environment is no different. Without an understanding of all that nursing in contemporary healthcare contexts means, you may find yourself disillusioned by the dichotomy between what you think nurses and nursing should be and what they actually are.

Let’s be very clear about one thing at this point; while the challenges associated with nursing in contemporary practice environments have escalated, the rewards, the satisfaction and the sheer joy of knowing you have made a real difference to peoples’ lives are as wonderful today as they have always been. You will be inspired as you observe committed nurses providing extraordinary care despite the clinical challenges they encounter. Your mission (should you choose to accept it) is to navigate your way through what may sometimes seem to be a maze. This book prepares you for your journey into this dynamic and exciting clinical environment.

1.2 The clinical placement—what it is and why it matters

Clinical placements (sometimes called clinical practicum, work-integrated learning or fieldwork experiences) are where the world of nursing comes alive. You will learn how nurses think, feel and behave, what they value and how they communicate. You will come to understand the culture and ethos of nursing in contemporary practice, as well as the complexities and challenges nurses encounter. Some students say that clinical placements change the way they view the world. Whether this is true for you will depend, to a large extent, on how you approach it. Most importantly, clinical placements provide opportunities to engage with and care for clients, to enter their world and to establish meaningful therapeutic relationships.

1.2.1 Clinical learning

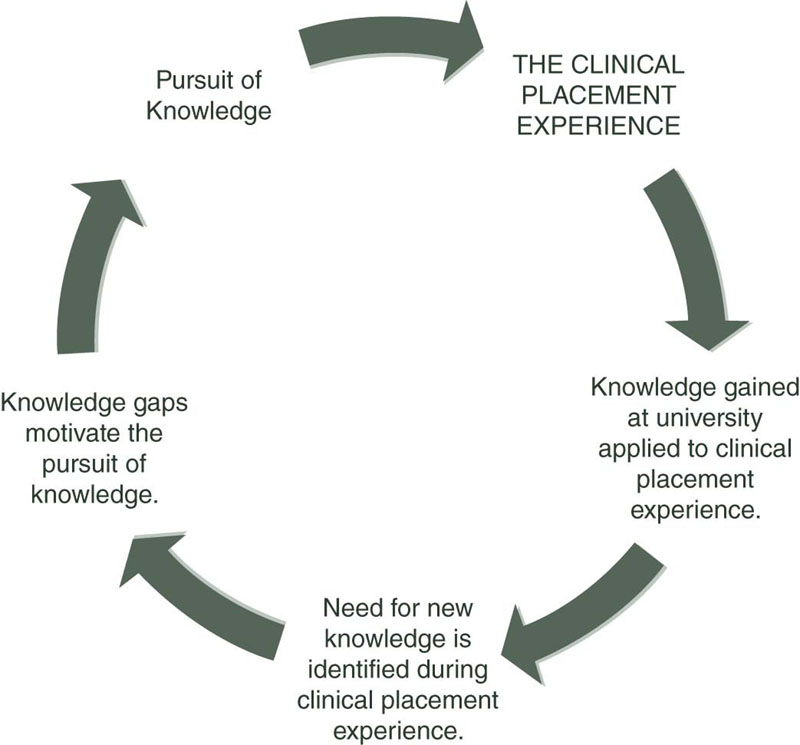

Skilled and knowledgeable nurses have a significant impact upon the clients and communities they serve. Quality nursing care results in reductions in patient mortality and critical incidents, such as medication errors, patient falls, hospital-acquired infections and pressure ulcers (Aiken et al. 2003; Needleman et al. 2001). Clinical placements are where you apply the knowledge gained through your academic pursuits to the reality of practice. Additionally, analysis and critical reflection on your clinical experiences will make explicit the areas in which you need more knowledge and experience. In this way knowledge pursuit and clinical application become an ongoing cycle of learning (Figure 1.1).

Clinical placement patterns

Depending on where you study, your clinical placement patterns will vary. Your placements may be scheduled in a ‘block’ pattern, in which you attend for a week or longer at a time, you may attend on regular days each week or you may have a combination of attendance patterns.

Clinical placement settings

Clinical placements occur across a broad range of practice settings and vary depending on where you study. Each clinical area has inherent learning opportunities. Typically, you can expect to undertake placements in some or all of these areas:

• medical/surgical units (such as cardiac, respiratory, urology, orthopaedics, haematology, etc.)

• critical care units

• older person services

• mental health services

• community health settings

• primary healthcare settings

• maternal and child health services

• disability services

• Indigenous health services

• rural and remote areas

• public and private health facilities.

In Chapter 6, nursing experts from a range of clinical practice areas share their insights. They provide an overview of the area, the unique learning opportunities available, the preparation required and the challenges that you may encounter.

At some educational institutions students also engage in simulated learning experiences, which may replace or complement clinical placement hours. Simulation sessions provide many learning opportunities, for example:

• students can be actively involved in challenging clinical situations that involve unpredictable, simulated patient deterioration;

• students can be exposed to time sensitive and critical clinical scenarios that, if encountered in a ‘real’ clinical environment, they could normally only observe;

• students can access and use clinically relevant data in a structured way;

• immersion in simulation can provide opportunities to apply and synthesise knowledge in a realistic but non-threatening environment;

• students can make mistakes and learn from them without risk to patients;

• students can develop their clinical reasoning ability in a safe environment which can improve patient safety and lead to improved patient outcomes when these skills are applied in practice;

• opportunities for repeated practice of requisite skills and formative and summative assessment can be provided;

• debriefing and immediate opportunities for reflection and remediation can enhance learning.

Clinical supervision and support

Various models of facilitating students’ learning are used during clinical placements. The model implemented depends upon various factors, such as the context, the number of students and the student’s level of experience.

You may have a clinical educator (sometimes called a facilitator) to guide your learning and to support you; and/or you may have a ‘mentored’ or ‘preceptored’ placement, in which you are guided by a clinician from the venue. You may also have the support of an academic visiting the clinical site. Regardless of the type of support provided during placement, it is important to remember that, to a large extent, the success of your placement will depend on what you bring to it and your degree of preparation and motivation.

Your feelings before, during and after your clinical placement experience will vary. Students report experiencing some or all of the following emotions: excitement, exhilaration, pride, confusion, anxiety, fear, apprehension, tension and stress. Your educator or mentor (or both) is there to support you. It is important to share your feelings and to seek further guidance and support whenever necessary. During and/or at the conclusion of your placement you will be provided with opportunities for debriefing, for reflection and for talking about your experiences.

What’s in a name?

When describing the people nurses care for, we use the terms patient, client, healthcare consumer and resident. We made the decision to use these different terms deliberately. When you undertake clinical placements you’ll quickly become aware that different terms are used to refer to those you care for, depending on the context of practice. We define the terms here so that you’ll have a clear understanding of their meaning.

‘Patient’ is still the most common term used to describe a person seeking or receiving healthcare. It does carry some negative connotations, however; as traditionally a ‘patient’ was defined as someone who passively endured pain or illness and waited for treatment. Although patients are becoming more active and proactive when their health is concerned, the term ‘patient’ is still the one you’ll hear most often.

‘Client’ refers to the recipient of nursing care. Client is a term that is inclusive of individuals, significant others, families and communities. It applies to people who are well and those who are experiencing health changes. It is intended to recognise the recipient of care as an active partner in that care and the need for the nurse to engage in professional behaviours that facilitate this active partnership. The term ‘client’ is often used in mental health and community health services.

‘Resident’ most often refers to a person who resides in a high- or low-care aged care facility or a person with a developmental disability who lives in a residential care facility, either short or long term.

Healthcare consumer is considered by some to be a politically correct term, particularly in the age of consumerism. Some writers (e.g., Sharkey 2003) suggest that the terms patient and client deny the health-services user the rightful participation that is now expected in the Australian healthcare system. These commentators advocate that the term ‘consumer’ denotes a more active role in the planning and delivery of health services. However, it is important to note that many people deliberately avoid the use of the word ‘consumer’ when describing the people nurses care for, claiming that consumer is a negative and rather narrow definition of human beings in relationship to sickness and health. Iedema et al. (2008)identify the patient/consumer as a co-producer of health, involved in decision making and designing their own care.

As you can see there are divided opinions about the ‘correct’ terms to describe those we care for. We suggest that you keep an open mind during your clinical placements.

1.3 Person-centred care

At this early stage in the book it is important to acknowledge that nursing, and therefore clinical placements, are focused primarily on the patients for whom we care—and everything else should take second place. For this reason we now turn to a discussion of person-centred care.

‘Person-centred care’ is a term that has become prevalent in nursing over the past decade. It is a concept that nurses highly value, particularly in the increasingly complex and busy environments typical of contemporary practice. Person-centred care is considered integral to quality nursing. You will hear this term used frequently, so it is important to understand its meaning.

Person-centred care is underpinned by principles such as empathy, respect and a desire to help a person lead the life they want. Person-centred care places the client at the centre of healthcare and identifies consideration of his/her needs and wishes as paramount (Victorian Government Department of Human Services 2006). This principle aligns closely with the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Councils (ANMC) professional standards and codes of practice which specify that nurses:

A recent Australian study found that key attributes of person-centred care include the existence of a therapeutic relationship between nurses and patients, the provision of individualised care and evidence of patient participation (Bolster & Manias 2010). Where a person-centred approach to nursing is adopted, there is more holistic care with evidence that it may increase patient satisfaction, reduce anxiety levels among nurses and promote teamwork among staff (McCormack & McCance 2006).

Person-centred care has been defined by McCormack (2004)as being concerned with the authenticity of the individual, that is, their personhood. Within this approach nurses must recognise patients’ freedom to make their own decisions as a fundamental and inalienable human right. It is also important to appreciate that person-centred care does not discount the rights and wishes of people who are experiencing mental illness or cognitive changes, such as dementia.

Person-centred care involves seeing the person not just the patient, client or resident. Just as being a nursing student is only one aspect of who you are, being a patient, resident or client is only one dimension of personhood. The language used to describe the people for whom we care is often indicative of the extent to which our practice is person-centred. For example, by referring to a person as ‘the bowel resection in room 23’ or ‘the one with dementia who needs an intravenous (IV) infusion’, their personhood becomes subsumed and they become no more than their disease, their symptoms or a task that has to be attended to.

While person-centred care may sometimes seem to be an unrealistic goal amid the busyness that characterises much of contemporary healthcare, person-centred care is not just another task. It is a way of being with another, of upholding their dignity and interacting in a meaningful and memorable way. Person-centred care also refers to appreciating that each person has a unique and valuable life history. In nursing we have the privilege of being afforded glimpses of our patients’ life history and we share moments in their life journey. Certainly, in long-term facilities the opportunities to discover and appreciate each person’s life story are abundant. Life stories are a way of acknowledging that each individual has a coherent and evolving identity which spans past, present and future.

Reflection

Reflect on the following ‘real-life’ stories. Consider how you will practise in a way that acknowledges and respects each individual’s personal beliefs, values and needs. Think about how knowing a person’s life history may influence your ability to provide person-centred care.

In dementia-specific units, ‘dolls’ are sometimes introduced as a form of therapy. They have strong symbolic meaning and provide purpose, nurture and healing for some people with dementia. ‘Alice’ (an 82-year-old resident) was very attached to a ‘dementia doll’. She held it closely throughout the day and became distressed if anyone tried to take it away. At night she would wrap it in a blanket and gently place it next to her bed. Alice had never been married, nor did she have children, so no one really understood her attachment to the doll. Some of the nurses were bemused, and others a little frustrated when she struggled to hold onto the doll when they were trying to help her dress. When speaking to family members at her funeral the nurses found out that Alice had become pregnant when she was 16 and had been forced to give her baby up for adoption. The nurses exclaimed: ‘no wonder she would never let go of the doll … that was the baby she had given away … if only we’d known.’

How might knowing more about Alice’s life history have influenced the nurses’ ability to provide person-centred care?

Megan was an 18-year-old girl admitted to a palliative care unit with terminal cancer. All the nursing staff on the unit had become involved in her care, particularly the nurse unit manager. When Megan realised the severity of her condition and that she would not be returning home, she became terribly depressed. The manager spoke to her family and organised a secret ‘rendezvous’ in the hospital basement, at the service entrance. When Megan was wheeled down to the basement in her hospital bed, surrounded by infusion pumps, syringe drivers etc, she was greeted by her adored Maltese Terrier, Zoe. The look of absolute joy on Megan’s face as Zoe snuggled into her arms for the last time was unforgettable.

This caring manager’s organisation of a ‘rendezvous’ was a challenging feat, and one that may have contravened a few hospital rules. What elements of this nurse’s actions portrayed the true meaning of person-centred care?

Mrs Trent was in her eighties and admitted for investigation of low haemoglobin levels. A colonoscopy was scheduled, but Mrs Trent was adamant she did not want the procedure, and despite having it explained to her in detail, she refused to consent to it. However, at times Mrs Trent behaved in a way that indicated she may have been confused. For example, she accused the staff of stealing her purse, which was subsequently found not to have been lost. She was terribly frightened of the procedure. Eventually, her son was contacted and signed the consent for her. The night before the procedure Mrs Trent was supposed to commence drinking several litres of the bowel-preparation solution. At first Mrs Trent refused to drink it, but despite her being distressed, she was eventually coaxed to drink some of it by some of the senior nurses. Then they left a nursing student to stay with Mrs Trent, with the instruction to ‘keep her drinking the solution, until it is all gone, otherwise the colonoscopy will be a waste of time.’

Was person-centred care evident in this scenario? What would you do if you found yourself in a similar situation? In Chapter 4, we explore some of the ethical implications of these types of situations more fully.

![]() Learning Activity

Learning Activity

One of the challenges we would like to set you is to begin to reconceptualise your nursing care as person-centred. For example, what would person-centred pain management look like? What is person-centred communication when caring for a person with dementia? These are important questions for you to discuss with fellow students, lecturers and the nurses with whom you work.

1.4 Models of care

Undertaking clinical placements in different facilities and units will provide you with exposure to different models of patient care. A model of care provides an approach to the way that patient care is organised within a clinical unit and relates to the way that nurses and other healthcare workers within the team structure patient-care activities. Models of care are currently receiving considerable attention in relation to patient safety and quality (Chiarella & Lau 2007). Differences in models of care implemented within units or wards can be attributed to several factors, including the current worldwide shortage of nurses (Fowler et al. 2006) and skill mix (numbers, types and levels of experience of nurses and healthcare workers; Davidson et al. 2006). Models of patient care may include (NSW Department of Health 2006; Duffield et al. 2007):

Task-oriented nursing refers to a model in which nurses undertake specific tasks related to nursing care across a group of patients. Some examples of task allocation may be when a nurse showers all or most of the patients in a ward while another nurse administers the medications for the same group of patients. In this model of care delivery, nursing care relates to sets of activities that are performed by nurses for patients.

Team nursing is a model that ‘teams’ experienced nurses with less experienced or casual staff to achieve nursing goals using a group approach. The size and skill mix of teams can vary from unit to unit and across healthcare facilities.

Patient allocation models were developed because nurses recognised the need for total patient care. The implementation of these types of models results in nurses getting to know the whole patient, rather than patient’s care being organised as a series of tasks. A nurse will be allocated to his or her patients (the number is dependent on factors such as patient need, staff mix and ward policies) to undertake all nursing care for these allocated patients.

Primary nursing is a model in which the nurse promotes continuity of care over a period of time and focuses on patient and nurse relationships. Delegation to other nurses occurs when the primary care nurse is off duty (Duffield et al. 2007).

The model of care delivery implemented on a ward depends on a range of factors, including the degree of innovation and commitment by the people involved. Some models work better when there are sufficient numbers of highly qualified staff, such as registered nurses (RNs) to deliver care; others may focus on supporting less experienced staff using a team approach (NSW Department of Health 2006).

![]() Learning Activity

Learning Activity

On your next placement, identify the model of care delivery used in the unit. Discuss with the nurses the reasons for the implementation of this model and its advantages and disadvantages. Find out where student nurses fit into this model.

1.5 Competent practice

Competence is a complex concept that is difficult to define and difficult to measure (FitzGerald et al. 2001, Watson et al. 2002). Many people make the mistake of thinking that competence simply means the satisfactory performance of a set task, but competence is much broader than that. The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC) defines competence more comprehensively as ‘The combination of skills, knowledge, attitudes, values and abilities that underpin effective and/or superior performance in a profession/occupational area’ (ANMC 2006, p. 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree