17 The respiratory system

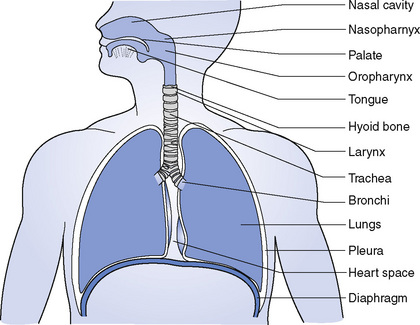

All living cells require a constant supply of oxygen to carry on their metabolism. Oxygen is in the air, and the respiratory system is constructed in such a way that air can be taken into the lungs, where some of the oxygen is extracted for use by the body and at the same time carbon dioxide and water vapour are given up. The organs of the respiratory system (Fig. 17.1) are:

|

The nose

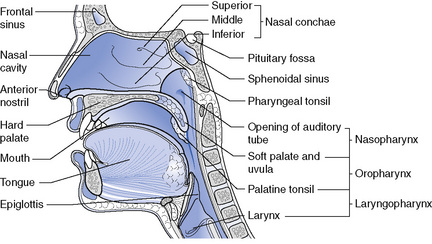

The external nose is the visible part of the nose, formed by the two nasal bones and by cartilage. It is both covered and lined by skin and inside there are hairs that help to prevent foreign material from entering. The nasal cavity (Fig. 17.2) is a large cavity divided by a septum. The anterior nares are the openings that lead in from the outside world and the posterior nares are similar openings at the back, leading into the pharynx. The roof is formed by the ethmoid bone at the base of the skull and the floor by the hard and soft palates at the roof of the mouth. The lateral walls of the cavity are formed by the maxilla, the superior and middle nasal conchae of the ethmoid bone, and the inferior nasal concha. The posterior part of the dividing septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and by the vomer, while the anterior part is made of cartilage.

The pharynx

The roof of the pharynx is formed by the body of the sphenoid bone and, inferiorly, it is continuous with the oesophagus (see Fig. 17.2). At the back it is separated from the cervical vertebrae by loose connective tissue, while the front wall is incomplete and communicates with the nose, mouth and larynx. The pharynx is divided into three sections: the nasopharynx, which lies behind the nose; the oropharynx, which lies behind the mouth; and the laryngopharynx, which lies behind the larynx.

The larynx

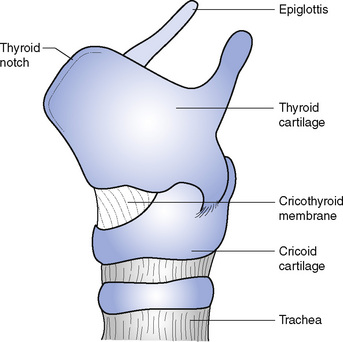

The larynx is continuous with the oropharynx above and with the trachea below (see Fig. 17.2). Above it lies the hyoid bone and the root of the tongue. The muscles of the neck lie in front of the larynx, and behind the larynx lies the laryngopharynx and the cervical vertebrae. On either side are the lobes of the thyroid gland. The larynx is composed of several irregular cartilages joined together by ligaments and membranes (Fig. 17.3).

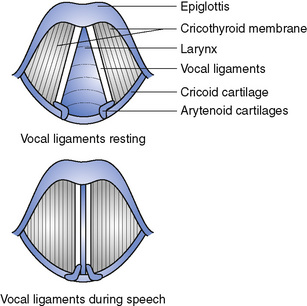

The hyoid bone and the laryngeal cartilages are joined together by ligaments and membranes. One of these, the cricothyroid membrane, is attached all round to the upper edge of the cricoid cartilage and has a free upper border, which is not circular like the lower border but makes two parallel lines running from front to back. The two parallel edges are the vocal ligaments (Fig. 17.4). They are fixed to the middle of the thyroid cartilage in front and to the arytenoid cartilages behind, and they contain much elastic tissue. When the intrinsic muscles of the larynx alter the position of the arytenoid cartilage the vocal ligaments are pulled together, narrowing the gap between them. If air is forced through the narrow gap, called the chink, during expiration, the vocal ligaments vibrate and sound is produced. The pitch of the sound produced depends on the length and tightness of the ligaments: an increased tension gives a higher note; a slacker tension a lower note. Loudness depends on the force with which the air is expired. The alteration of the sound into different words depends on the movements of the mouth, tongue, lips and facial muscles. An inflammation of the larynx is called laryngitis and this may be caused by infections or chemicals. Laryngitis interferes with speech and leads to a hoarse voice.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree