In chapters 1 and 2, we have introduced you to our ideas about what becoming a reflective practitioner is about, and to some of the models and theory that may help you on your journey. In this chapter, we show you how the Reflective Timeline works. You will see how your professionalism is one of the steps on a journey that involves others, illustrating the importance of professional and inter-professional working. You will understand where your involvement starts and where it ends.

Through studying this chapter and engaging in the exercises, you will be able to:

• locate your own profession within the wider context of your role

• recognize the importance of each stage along the time-line

• reflect on your own timelines in a given situation

In any Reflective Timeline there are many different professionals involved at each stage. For example, in the story that unfolds in this chapter, the timeline starts with a schoolteacher; however, a midwife, a family doctor, a social worker and a children’s nurse are just some of the people who are also part of this timeline. Many other professionals will be part of any care or support that you give. Each professional involved comes from a different perspective and has a different set of skills, but you will all share similar professional values.

Being a professional

You will have noticed that we use the word ‘professional’ frequently in this book and regularly ask you to be aware of and respect the professional role of others, so it is worth taking a few moments to think about what this might mean.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Stop and think for a moment: identify someone you know whom you would describe as a ‘professional’. Ask yourself what it is that makes them a professional and jot down these key features.

In common language we use the word ‘professional’ in many different ways, so it does not have a clear definition. In boxing and many other sports, someone may be professional or amateur. Both could be equally skilled and respected in their field; the difference in title reflects whether they are paid or not. In other circumstances, ‘profession’ may be contrasted to ‘vocation’. ‘Vocation’ has religious connotations, and is strongly associated historically with some health professions such as medicine and nursing, with doing social work and with religious duty. However, in contemporary language it has a different meaning. ‘Vocational’ qualifications usually refer to courses leading to employment that have a practical or applied element. ‘Vocation’ may be associated with lower pay, or with voluntary unpaid work, adding another confusing dimension.

The academic literature does not really clarify these definitions. Van Mook looked at assessing professionalism in medical students, putting the emphasis on professional behaviour rather than personality traits, and relating this to ethical reasoning and behaviour (van Mook, van Luijk, O’Sullivan, The Reflective Timeline Wass, Schuwirth & van der Vleuten, 2009). Further research (Rogers & Ballantyne, 2010) adds the capacity for reflection to the attributes. This approach is used in chapter 7 where we discuss reflection and ethical practice, particularly where there are difficult decisions to be made, and where you, the professional, may have made a mistake.

Further research with dental students used eight ‘professional attributes’ to analyse professionalism (Pau & Croucher, 2003, p. 124):

• Ability to recognize personal/professional strengths and limitations

• Ability to listen attentively

• Caring and compassionate nature

• Spirit of curiosity

• Unprejudiced respect for others transcending gender, culture, background, etc.

• Ability to cope with stress, uncertainty and setback

• Commitment to manage your own learning

• Ability to communicate effectively with each other

For others, for example Litchfield, Frawley and Nettleton (2010), the emphasis is on being ‘work ready’, and although there are some overlaps, particularly regarding communication, their list is different (p. 521):

• Ethics and professionalism

• A global perspective

• Communication capacity

• Ability to work well in a team

• Ability to apply knowledge

• Creative problem solving and critical thinking skills

As you can see, both of these sets of attributes also link closely to ethical practice, and have overlaps with the virtues identified in chapter 1 (Banks & Gallagher, 2009).

These studies provide just a small example of the many different definitions in use. They represent a move away from a vocational ethos towards skilled, highly employable, reflective, ethically aware individuals.

Working inter-professionally

| EXERCISE |

In the section above, we asked you to identify someone whom you thought of as ‘professional’, and we identified a number of shared attributes, regardless of which profession you or they may practise. What we would like you to do now is to think about all of the professionals who interact with your role. Try focusing on a client, patient or service user with whom you have had contact – someone whom you needed to support or help professionally. Focusing on that person, and what you know about their lives, make a list of all the professions he or she is likely to have encountered over the last few weeks.

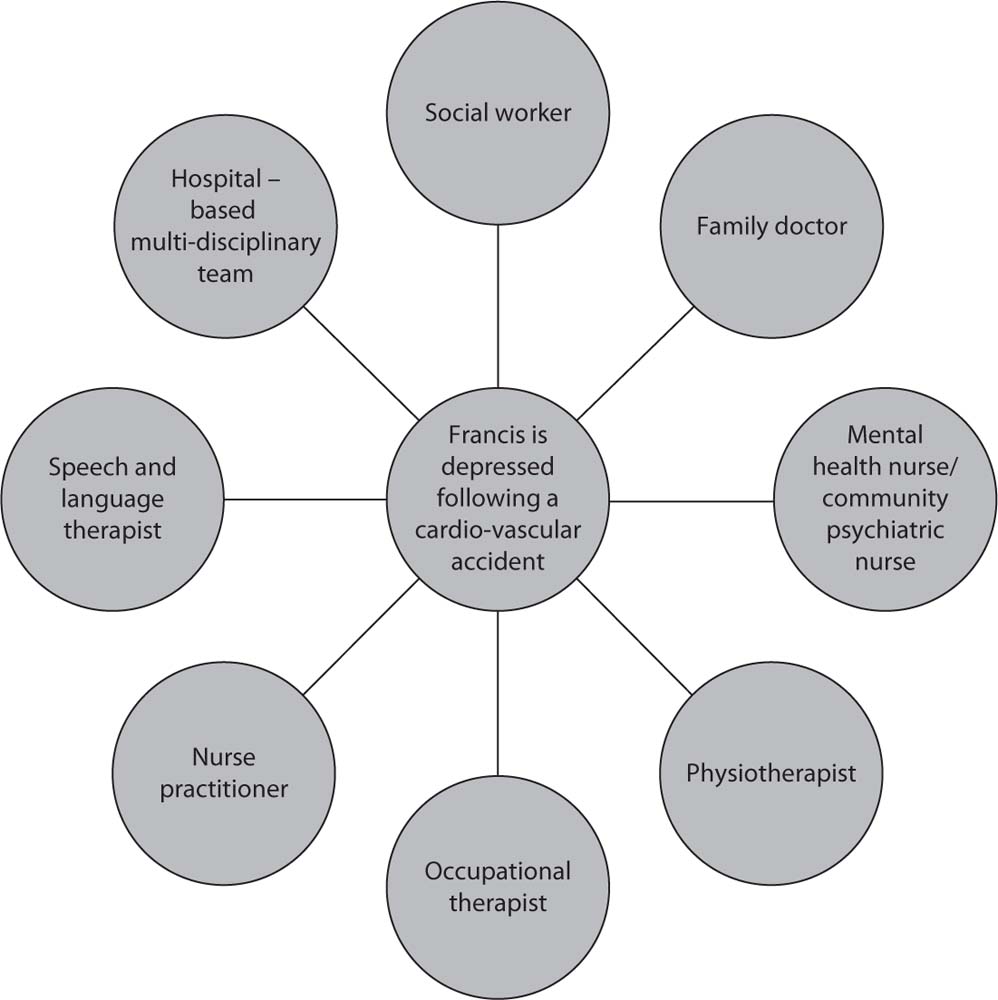

We identified Francis, who is depressed following a cardio-vascular accident.

The definitions of ‘professional’ identified at the start of this chapter all relate to individual people; training for your profession will include specific knowledge and skills that make you, for example, a social worker, dentist, doctor, allied health professional or nurse. However, it is rare for any health or social care professional to work in isolation, as the focus of our roles is usually the health or wellbeing of individuals, who will have contact with many professionals. It is equally rare for an individual’s care or support to be managed by a single, isolated professional.

The World Health Organization published a far-reaching report on inter-professional education and collaboration (WHO, 2010), which is a worthwhile read for any professional interested in the wellbeing of the population. Whilst global catastrophes, war and famine may seem a long way from your own area of practice, the message that inter-professional collaboration is essential is hard to dispute. Interestingly, the difficulties that health and social care professionals seem to have in working together are not always recognized in other sectors. A refreshing perspective in the cultural industries is about working together creatively, rather than being embroiled in differences and in professional ‘politics’ (David, 2011).

Figure 3.1 An inter-professional circle

| SEARCH AND EXPLORE |

There is a huge body of literature on inter-professional learning and education. Try searching for the ‘Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education CAIPE’. Look on websites from your profession, or national organizations such as the ‘Higher Education Academy’, and you will find reports, reviews of the literature, research, special interest groups and much more.

Shared values

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Factors included in all of our professional codes and standards of ethics are likely to be respect for others, a primary focus on the person or people for whom you are responsible rather than yourself, the ability to suspend personal judgement, and the ability to work collectively, even with people you may not like or agree with, towards a common goal. In practice these standards are hard to meet and we will explore these issues further in chapters 7 and 8, but they should be at the heart of your professionalism.

This chapter in particular shows how each Reflective Timeline can be seen in relation to others.

Nilam’s Day

When Nilam, ten, is getting changed for sport, her teacher Mr Parker notices that she has a burn on her leg. When he asks Nilam what has happened, she says that she was trying to iron her skirt while she was wearing it and got the iron too hot. The teacher asked why she was ironing her skirt when she was wearing it. Nilam explains she was in a hurry to get her younger siblings, aged six and two, dressed because her mother is ill and couldn’t get out of bed.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

From your professional perspective, what is the first thing in the story that jumps out at you?

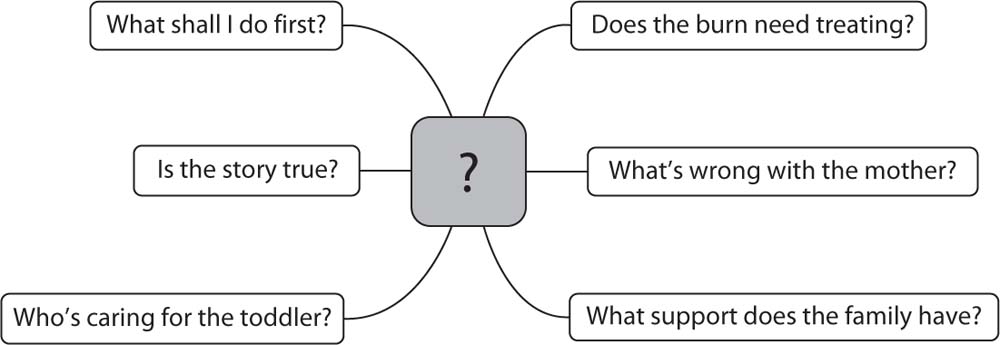

Figure 3.2 First thoughts

Depending on your area of expertise, your primary concern may be anything from treating the burn to your legal responsibilities for safeguarding children.

| TIME FOR REFLECTION |

Thinking about the story again, what are your perceptions now? Do you have questions you want to ask? What are they? Have they changed? If they have, you are already practising reflection.

The Reflective Timeline

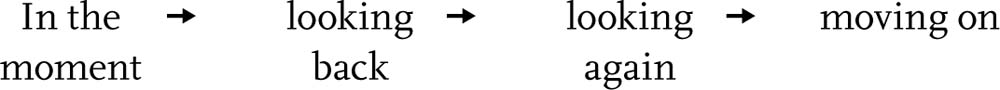

All reflection has a timeline to it. We suggest that this is likely to fall into four categories:

In the moment

In the moment

This is the moment, when working with Nilam, that your professionalism takes over and you make immediate decisions. It is when you prioritize your response to the situation. There is also an emotional undercurrent: you may be feeling things such as concern for Nilam, frustration at her mother, anger that no one has realized what the situation is, anxiety about the two-year-old. You will be acutely aware of the way in which your words and actions are affecting Nilam’s wellbeing. For example, she says her mother is ill but you make the decision not to press her to name the illness; neither do you jump to any conclusions about the situation. You know that the decisions you make in this moment will have far-reaching effects. You may be holding conflicting ideas because you have not had time to check what the real situation is. You also have to manage this problem in real time, continuing with all other aspects of your role and aware of the safety and needs of the other children involved.

Your Reflective Timeline is in this moment, but is just one of many that will be occurring. Other professionals, such as the family doctor, social worker and occupational therapist, may be at different stages of reflecting about this family and their professional role. Nilam’s burn may be the trigger for a new timeline for them, or a continuation of existing reflections.

Take a moment to move away from Nilam’s story and think about an incident in your own work which has disrupted the normal running of your day: reflection in the moment happens in real time. A problem must be solved and you may have to think on your feet. Experience and your professional learning will already have taught you some of the skills you need. Your reflections are focused on making immediate decisions, but the more experienced and skilled you are the more likely you are to be thinking of the medium-and long-term consequences of your actions. Reflection at this time is fluid. It moves and jumps, accepting and rejecting decisions. Just like Nilam’s teacher Mr Parker, you will be emotionally engaged. ‘Emotional intelligence’ is a phrase used to describe the way in which we relate to others, and use all of our senses to understand and inform our actions and behaviour (Higgs & Dulewicz, 2000).

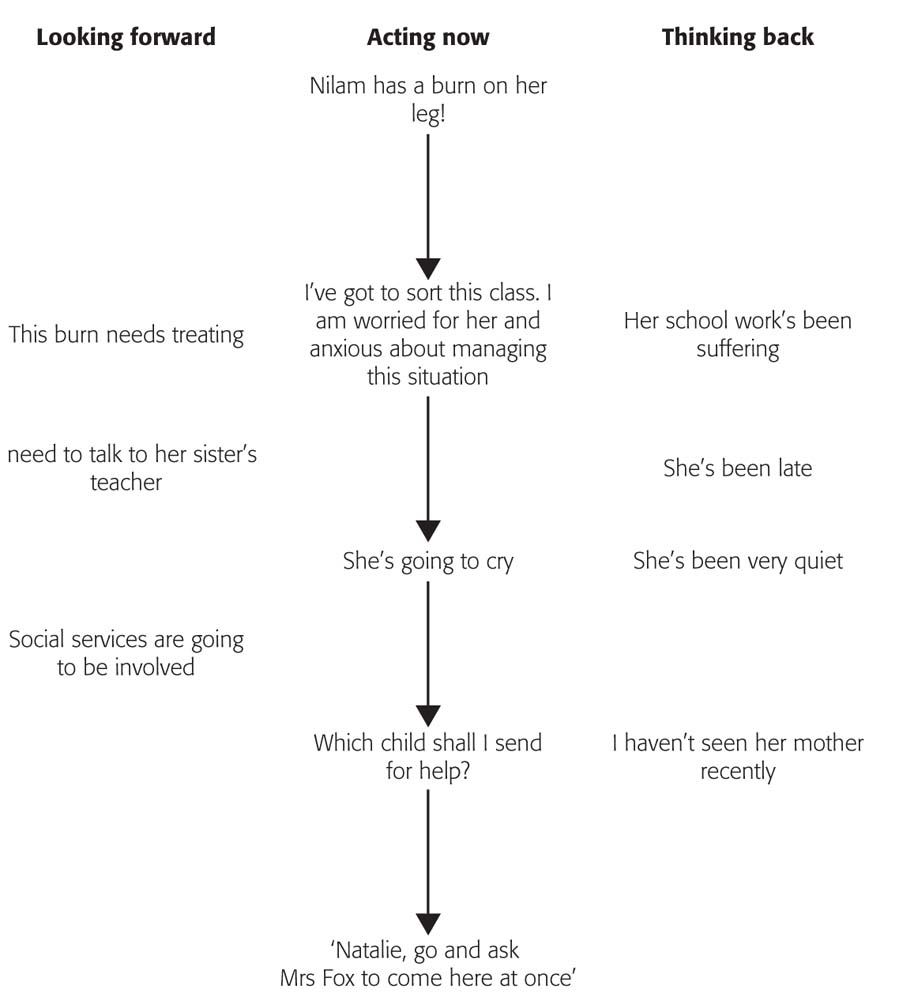

Returning to Nilam, Mr Parker’s thought process (much condensed) probably goes something like this:

Nilam is in pain and I’m concerned: why’s she come to school like this? How did the mark get there? I’ve got twenty-five kids here ready for PE. I need help. Nilam’s tired and upset. Alfie’s got his head stuck in his tee-shirt. I need to take Nilam out of this situation but am responsible for this class. I don’t want to send her away for help on her own. I need another adult here. Nilam is crying. Everyone is asking her questions. I need help fast. I’ll send a child to get Mrs Fox here so I can concentrate on Nilam.

The teacher in this situation is using all of his senses. He knows from the noise in the room that the other children are becoming frustrated. They can see that Nilam is upset. They can smell that her clothes aren’t washed.

Mr Parker has to cope with what is happening in the moment and with competing immediate needs. He doesn’t over-reach himself by trying to deal with the class and Nilam at the same time. A good reflective practitioner will always be thinking forwards and backwards to try to make sense of the situation. Figure 3.3 tries to capture the multiple thoughts that go alongside reflection in the moment.

Figure 3.3 Reflection in the moment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree