Chapter 7 The politics of health promotion

What is politics?

Heywood (2000) identifies a fourfold classification of politics:

Power is distributed unequally worldwide, and globalization has contributed to increasing the divide between high-income regions, e.g. Europe, the USA and Canada, and low-income regions e.g. in sub-Saharan Africa. More than 10 million children under the age of 5 die each year, almost all in poor countries or poor areas of middle-income countries (Jones et al 2003). Over half of these deaths are caused by undernutrition and lack of access to safe water and sanitation (Labonte & Schrecker 2007).

Political ideologies

One of the arenas in which power relationships are manifest is social policy, which may be defined as planned government activities designed to maintain, integrate and regulate society. This includes both welfare and economic policies, ranging from national legislation to local policy developments within local authorities. (See Chapter 11 for a discussion of Developing Healthy public policy.)

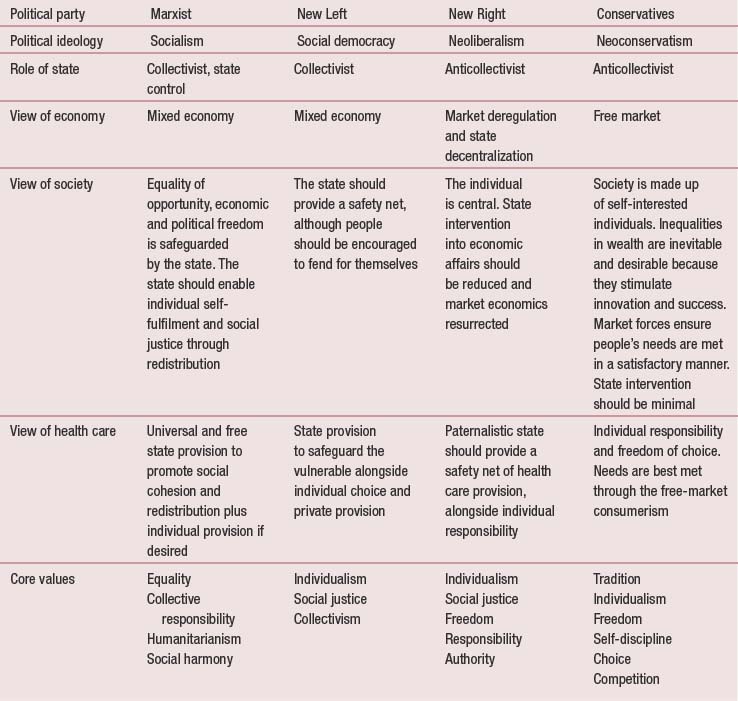

Government policies are determined according to its beliefs and ideas – its ideological position. Different political positions give rise to certain types of policy interventions. Analysts have identified many different frameworks and have pointed to the shift in ideologies since the 1960s (Bambra et al 2008). The old mid 20th-century spectrum of political belief from the hard-line left (Marxism) via Socialism and Liberalism to the right wing (Conservatism) no longer describes accurately the political beliefs and ideologies of nations and parties. Globalization, the demise of Soviet rule over Eastern Europe, and the permeation of nation boundaries through international trade and the forces of nature have given rise to new political beliefs, in particular, the rise of neoliberalism and neoconservatism. These changes are summarized in Table 7.1.

Views on health and health promotion reflect a complex mix of values and beliefs which, in turn, reflect different political ideologies. The central proposition of this chapter is that health, and therefore health promotion, is political. Health promotion takes place in the policy area and embodies ideological values. Ideology is ‘a system of interrelated ideas and concepts that reflect and promote the political economic and cultural values and interests of a particular societal group’ (Bambra et al 2003, p. 18). The ideological viewpoints of different political parties vary widely. Key beliefs in relation to promoting health on which people differ concern:

Neoliberalism has evolved since the 1960s as an attempt to combine the twin goals of social justice and economic growth. Neoliberalism is committed towards reducing state intervention in the economy and advocates market deregulation as the means to economic growth and social welfare. Such views are associated with the rugged individualism of Margaret Thatcher who famously asserted: ‘there is no such thing as society, only individuals and their families’.

Socialism is based on a belief in equality, fellowship and community, or a sense of responsibility for others. The government has a key role to play in ensuring everyone’s basic needs are met, redistributing material resources and promoting a sense of social stability and cohesion. Social democracy, whilst embodying the same core beliefs, also embraces the notion of individual choice within a free market.

Globalization

Globalization, defined primarily as the economic processes of free trade supporting a global marketplace, is another reason for the shifting positions of political parties. No political party can ignore the immense power of global capitalism, which reaches across the world, ignoring national or regional boundaries. McDonalds, Microsoft and Philip Morris are known worldwide for promotingjunk food, internet communication and tobacco respectively. Proponents of globalization argue it is more efficient and allows poorer countries to benefit from the technological advances of more developed countries. Critics of globalization argue that it destabilizes national economies, reduces everything to a market value and increases inequalities of wealth and health. It has been argued that the socioeconomic determinants of health have become globalized, leading to increased inequalities between rich and poor countries as well as within countries (Labonte & Schrecker 2007). Whatever the stance adopted, health promotion needs to develop and function within an increasingly global economy and world.

Globalization in politics is mirrored by globalization in health. Health risks are now increasingly global in their scope and spread, fuelled by the displacement of people (through war and natural disasters), global trade and movement of people and products. For example, the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) requires continued vigilance and concerted action by nations and international agencies (Kickbusch & Seck 2007).

There are many important challenges to health and health promotion posed by globalization. Lee (2003) identifies the following:

Equally, globalization opens up new possibilities – of networking, learning from others’ experience and sharing of resources – that could be used positively to promote and protect health. The World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Macroeconomics and Health in 2001 made the case for a reciprocal relationship between health and development, arguing that not only is development vital for health, but health is vital for development. The political challenge for health promotion is to foreground health as a valued goal and a key component of the global public good.

Health as political

In the WHO Alma Ata declaration (World Health Organization 1978) health was seen as both a human right and a global social issue. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 proclaimed that ‘everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of oneself and one’s family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care.’ Economic globalization has threatened these views of health as a human right. The People’s Health Movement (www.phmovement.org) is a group of political activists and advocates opposed to globalization. This group argues that it is health, not the economy, that should be prioritized.

Within nation states, the political context affects all areas of government policy that have an impact on health, both directly and indirectly. Bambra et al (2003) argue that health is political because power is exercised over it and its correlates (such as citizenship and organization). A recent WHO report (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003) identified 10 social determinants of health: social class gradient, stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food and transport. Evidence suggests that these social determinants of health are the best predictors of individual and population health, that they structure lifestyle choices and that they interact to produce health (Raphael 2003). This in turn leads to the notion of health as political and the outcome of national and international policy decisions. A strong welfare state that provides people with access to the social determinants of health is arguably the best means to promote health (Raphael & Bryant 2006).

The politics of health promotion structures and organization

Internationally and nationally health promotion has enjoyed varying levels of support throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The first International Conference on Health Promotion in 1986 led to the adoption of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986) whose five action areas (building a healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, developing personal skills, strengthening communities and reorienting health services) are still used widely. This was followed by conferences in Adelaide (1988), Sundsvall (1991), Jakarta (1997) and Mexico (2000) which identified additional areas for action. More recently, the Bangkok Charter (WHO 2005) outlines four key commitments:

A brief history of health promotion in the UK

1800–1900 Public health movement

Arose out of a conservative tradition of reluctant collectivism, that the state had to intervene to ensure national efficiency, economic advantage and social stability

1990s The rise of the market

Several commentators have argued that health promotion in the UK is currently facing a crisis of identity, and is in danger of being subsumed by the new public health (Orme et al 2007; Scott-Samuel & Springett 2007). Health promotion has always struggled to have a visible presence and its position within the National Health Service has led to it being viewed as a ‘Cinderella’ service subordinated to health care provision and the medical model. Since 1997 and the election of the New Labour government, health promotion has been sinking from view, with the disappearance of both its specialist workforce and its lead organization in England (Scott-Samuel & Wills 2007). Health promotion is now just part of the remit of a range of other agencies and staff, including public health practitioners, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), health trainers and community development agencies. In many countries the ascendance of neoliberalism combined with traditional biomedical approaches inhibits the wholescale adoption of the Ottawa Charter principles for health promotion (Raphael 2008; Wills et al 2008). For example, in Canada an epidemiological focus on population health has displaced health promotion.

BOX 7.1

BOX 7.1 BOX 7.2

BOX 7.2 BOX 7.3

BOX 7.3 BOX 7.4

BOX 7.4