Chapter Four. The policy context

Key points

• Defining policy

• The policy process

• The role of values and ideology

• Stakeholders’ impact on policy

• The ‘implementation gap’

• Policy agendas

• Policy debates and dilemmas

OVERVIEW

The previous chapter has shown how influential the available evidence is in affecting practice. Values and the policy context affect practice in an equally profound way. Although policy may sound remote from practitioners’ daily concerns, policies formulated at the national, regional, local and organizational levels have a major impact in determining practitioners’ priorities and ways of working. For example, many practitioners are aware of performance targets they need to meet, duties to work in certain ways, for example involving other agencies and the public as partners, and general principles of transparency and accountability. These issues have all been highlighted by policy making and implementation. Policy formation is a complex process affected by many different factors including political ideology and stakeholders’ agendas. Policy implementation is often thought of as an unproblematic administrative matter. However, this is not the case. Policy implementation is affected by frontline workers’ values and practices, and the same policy is often implemented in diverse ways with a variety of different outcomes. This chapter discusses the range of values underpinning policy formation and implementation, the policy process and key stakeholders, and some of the resulting dilemmas that affect practitioners.

Introduction

‘Policy’ is a vague term used in different ways to describe the direction of an organization, a decision to act on a particular problem, or a set of guiding principles directed towards specific goals (Titmuss 1974). The policy-making process has been defined as ‘still the only vehicle available to modern societies for the conscious, purposive solutions for their problems’ (Scharpf p. 349 cited in Hill and Hupe 2002, p. 59). The concept of policy therefore operates at different levels, describing both a specific input on a specific topic, and the values and ethos (the policy context) that inform specific goals and targets. The policy context includes values that are broadly consensual, such as democracy, and also values that are contested, such as managerialism versus professionalism. The policy context is therefore dynamic, charting public debates and the views of different lobbying and interest groups. Traditionally, public health policies are related to medical policies of disease surveillance and control. The programme of pre-school childhood immunizations and vaccinations and cervical and breast cancer screening programmes are examples of traditional public health policies. The broader concept of ‘healthy public policy’ has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO 1988) as the creation of ‘a supportive environment to enable people to lead healthy lives’. This broader concept means that most policy areas are implicated in the goal of better health for all. This is a reflection of the many different and complex factors that influence health and illness. The consequences of this are discussed in Chapter 11 in our companion volume (Naidoo and Wills 2009). Policy areas that impact on health include education, employment, neighbourhood renewal and regeneration, environmental issues, for example clean air, transport, food security and quality, and housing. At the international level, policies on an equally broad range of topics have a profound impact on health.

International policy on climate change: The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol (United Nations 1997) updated the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was adopted in 1992. The UNFCCC treaty was focused on stabilizing greenhouse gas in order to combat global warming. The Kyoto Protocol established legally binding commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5.2% (using 1990 as the baseline). The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997 and implemented in 2005. By 2008, 183 parties had ratified the protocol. The USA, the most significant producer of carbon emissions, has signed but not ratified the protocol. Many industrialized countries can achieve their agreed targets by offsetting their carbon emissions against carbon reduction projects in developing countries. This is done by developed countries purchasing carbon credits from other countries. For example, developing countries may initiate emission reduction projects such as sustainable forestry which can then be traded or bought by developed countries in order to meet their targets.

The policy context and broad macro-economic, environmental and demographic changes are major drivers of public health and health promotion. Practitioners tend to see public policy as beyond their remit, but policy exerts a powerful influence on practice.

The effect of policy on practice: The Victoria Climbie Inquiry Report

The official Inquiry Report (2003) into Victoria Climbie’s death from neglect and abuse whilst in the care of her great aunt and her cohabitee identified a ‘widespread organizational malaise’ amongst the health and social services involved. The Inquiry Report found a failure of all the key agencies involved to follow recommended procedures when child abuse is suspected. The Report made many recommendations regarding organizational structure, management, resourcing, procedures, practice and training. However, the death of Baby P in 2007 suggests that these recommendations and lessons have not yet been adopted and embedded in practice. In 2008, an inquiry into the death of Baby P was ordered by the Children’s Secretary. The inquiry found a failure to follow recommended procedures and many failings of management, supervision and practice.

Practitioners have to meet specified targets or requirements which have been identified in policy documents, for example to reduce waiting times in hospitals, or the requirement on health trusts and boards to work in partnership with local authorities. In some cases, this may mean diverting resources from established and effective practices, or innovative but well thought out strategies, to meet the new targets or goals. In other cases, the direction of an organization may be changed because of a new priority. For example, Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in England now have a duty to oversee public health.

As we outlined in our companion book Foundat-ions for Health Promotion (Naidoo and Wills 2009, Chapter 7), the development of health policy is an agreement on how health problems should be add-ressed, which involves a compromise between the following factors:

• ideological beliefs and values

• economic considerations

• political acceptability

• evidence-based research about ‘what works’.

In the UK, opportunities for practitioners and the public to influence policy have increased as a response to the government pledge for more open government. Consultation is invited on public health policies and strategies. For example, Every Child Matters: Change for Children, published in 2004, proposed joined up working between all the different agencies (educational, health and social) involved in children’s welfare. In 2005, the first Children’s Commissioner for England was appointed, with a brief to support and empower children and young people in all areas of life including health and economic well-being. As part of this process, the Commissioner is committed to giving children and young people a say in government and public life.

Policies are also informed by rational economic and evidence-based principles. For example, the Wanless (2002) Review on funding the NHS outlined three possible future scenarios. The third scenario, the ‘fully engaged’ model, posits services and a population which is informed and enthusiastic about protecting and promoting its health, and where research is productive in identifying effective communication and implementation of messages. Crucially, this fully engaged model is proposed within the Review as the most effective and lowest cost scenario in the long term. Within this scenario, public health investment is sound economic good sense, because better health leads to more productive employees and a stronger economy.

There have been calls for policy to be based on sound evidence about what works (Cm 4310 1999). However, there is a lack of evidence about effective public health and health promotion interventions (Macintyre et al 2001). For example, there is a solid research basis about the existence of inequalities in health, but very little research into comparing the effectiveness of different kinds of intervention aimed at tackling inequalities in health. A UK review of evidence-based health policy reported that only 4% of public health research focused on interventions, of which only 10%, or 0.4% of the total, focused on the outcomes of interventions (Milward et al 2001). In part, this is due to a traditional model of evidence based on individual cases and randomized controlled trials (see Chapter 3). This model is inappropriate for macro policies that are targeted at populations or communities. The evaluation of such policies is complicated because finding control populations that are not exposed to policy is difficult. Evidence-based policy is still in its infancy, due to competing influences and the lack of appropriate evidence.

As we have seen in earlier chapters, practitioners need a solid base on which to practise. The drive to evidence-based practice, quality standards and theory-driven interventions should make practitioners feel competent and secure. Yet many feel buffeted by policy initiatives and constant change. Policy takes place in a political arena, and many practitioners feel politics is removed from their core concerns. This may mean they do not engage with the political debates and feel policy makers are divorced from the reality of service delivery. People responsible for implementing policy may not be enthusiastic, and their frontline decisions may be crucial in dissipating the intended effect of policy. Conversely, enthusiastic and committed practitioners who feel they have had a valued input into policy formation can play a key role in achieving the intended outcomes of policies. To have a voice and be able to impact on policy making and implementation, practitioners need to be familiar with, and able to understand, health policy – its origins, its goals, the process, and its effects, both intended and unintended.

Understanding the policy process

Policy making has been defined as ‘the process by which governments translate their political vision into programmes and actions to deliver “outcomes” – desired changes in the real world’ (Cabinet Office 1999). National governments set the fundamental policy direction, while locally, policies develop incrementally. Walt (1994) identifies four phases in policy making that may occur at any level, whether national or local, and also shape any policy analysis:

1. Problem identification and issue recognition. Why issues get onto the policy agenda; which issues do not get addressed.

2. Policy formulation. The goals of the policy; different options are identified and analysed; costs and benefits of alternative policies are weighed; determining who formulates policy; how and where the initiative comes from.

3. Policy implementation. How policies are implemented; what resources are available; how implementation is enforced.

4. Policy evaluation. How progress is reviewed; setting up monitoring systems; how and when adaptations are made.

There is an assumption that policy is the result of rational decision making in which choices are evaluated and a solution is chosen to achieve objectives. Yet this rational process rarely takes place. As Simon (1958) argued, real world decision makers are not ‘maximizers’ who select the best possible course of action but ‘satisfiers’ who look for the course of action that is good enough for the problem at hand. Sutton (1999) also refers to other models of policy making:

• The incrementalist model, where policies which represent the least possible change are preferred, and policy is a series of small steps which do not fundamentally challenge the status quo.

• The mixed-scanning model, which represents a middle position where a broad view of possibilities is considered before focusing on a small number of options for more investigation.

Another way of theorizing the policy-making process is to distinguish between ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ models. Top-down theories propose a linear policy process whereby commands from higher up are seamlessly translated into practice on the ground (Buse et al 2005). Bottom-up theories recognize that practitioners are constantly modifying and creating policy on the ground, and that the policy process is collaborative and iterative rather than linear (Walker and Gilson 2004).

Dunsire (1978) first coined the phrase ‘implementation gap’ to describe the gap between planned policy and real life outcomes. The implementation gap is another way of describing the power of street level bureaucrats, and lends support to bottom up theories of the policy-making process.

Implementation of the single assessment process for older people

The single assessment process (SAP) is intended to reduce duplication of effort and facilitate seamless care across a range of agencies for older people. Dickinson (2006) studied a range of stakeholders involved in SAP and found many barriers to its implementation. These barriers included staff reporting a sense of disengagement from the process, finding the tool itself hard to use, feeling it involved activities beyond their area of practice, a lack of clarity about the role of others, and insufficient support from managers in recognizing the additional time SAP would take. Although the SAP was intended to reduce time and ease the assessment process, many practitioners did not carry out the process in the way in which it was intended.

None of these models describes the policy-making process accurately, although each model refers to elements of the process. Policy making mixes the scientific and the pragmatic; the broad vision with the narrow. The degree to which each element contributes to policy making differs according to the general political environment and the specifics of the policy under consideration.

Policy development

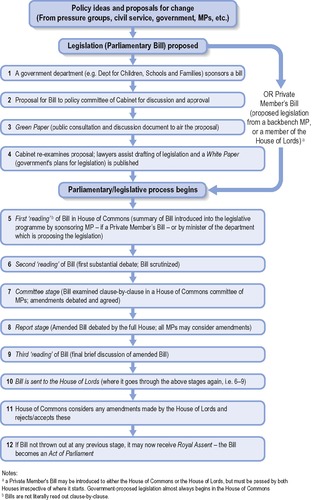

To understand the policy process, it is important to be familiar with the structure of the government. There is a complex process for the development of national policy in many countries based on democratic constitutions (e.g. England, Canada, Australia and the United States of America). In England, a new policy is signalled by the publication of a Green Paper for public consultation and discussion. After consultation and amendment, a White Paper, which is the government’s plans for legislation, is published. The policy then enters the parliamentary or legislative process, when the bill is scrutinized and amended by, first, the House of Commons and then the House of Lords. If the bill is not thrown out at any stage, it goes on to receive the royal assent, and the bill becomes an Act of Parliament. The policy has now become a legislation, which agencies are legally bound to follow. This process is illustrated in detail in Figure 4.1.

|

| Figure 4.1 • The policy process. Source: Blakemore (2003). |

Numerous factors affect the way in which policy is finally developed and implemented:

• situational: local or timely factors

• cultural: the values and ideologies dominant in the political environment

• structural: the political system and its processes.

This example illustrates the way in which policy reflects a pluralistic society of multiple interests where groups exercise influence. Some decisions are incremental, muddling through adaptations to circumstances, rather than contributions to strategic direction.

Alcohol pricing

Excessive alcohol consumption is linked to health, criminal and social harm, and associated costs. Despite strong evidence (Meier et al 2008) that alcohol consumption is linked to pricing, the UK government has stated that it does not see alcohol duty as a means of tackling problems associated with alcohol consumption. The government is, however, committed to introducing a new mandatory code to improve responsible retailing, for example halting happy hours and two-for-one promotions. The alcohol industry has lobbied against tax increases on alcohol, whilst publicans have launched a campaign for a minimum price of 50p per unit (to stop supermarkets’ loss-leading special offers). Campaigning groups such as Alcohol Concern have lobbied against price reductions and special offers, citing the harmful effects of increased alcohol consumption.

Issue recognition

For policy to be approved and enacted, an issue has first to become relevant and identified as a problem. In general there are three ways in which issues can get onto an agenda:

• following action by community groups leading to a groundswell of public opinion

• initiated by organizations or agencies concerned with the issue

• by key political figures who then mobilize support.

In addition, key incidents may also provide the trigger for gaining support and momentum for a policy, especially if they receive widespread media coverage and spark off a public debate.

Issue recognition, or agenda setting, relies on:

• problem definition

• receptive environment

• policy proposal.

The UK government, in common with many other developed countries (e.g. the Australian Government 2006) has identified obesity as a major issue and developed a national strategy (DH 2008). Why was this identified as a policy problem?

Current trends indicate that by 2050 nearly 60% of the UK population will be obese (Foresight Report 2008). Obesity is linked to a variety of health problems including hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol levels, asthma, arthritis and poor health (Mokdad et al 2003). These health effects not only impact on quality of life, but have significant economic implications for society as a whole. The causes of overweight and obesity are complex and include the increase in availability, marketing and low pricing of high energy-dense foods, and the increase in car use and sedentary leisure-time pursuits. Strategies to address these issues, adopted by both the English and Australian governments, emphasize the role of individual responsibility for health, and the importance of individual lifestyles in addressing problems. Getting obesity onto the policy agenda is a complex task that involves negotiating with powerful commercial interests and balancing contrasting ethical and ideological values relating to individual freedom and social responsibility.

There is an increasing international dimension in which the European Union and World Health Organization may set international agreements. For example, the World Health Organization’s first public health treaty, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, was agreed upon in 2003 (WHO 2003). It covers taxation, illicit trade, advertising and sponsorship.

Globalization may offer new opportunities for cooperation in public health, but it can also inhibit healthy public policy. Globalization has led to increased production of food and also enhanced the power of manufacturers and retailers at the expense of primary producers. Food producers are reliant on selling their products to a dwindling number of global companies, who can set their own terms and conditions. This has led to a loss of biodiversity as companies specify a limited number of crops for world markets. Whilst food scarcity is no longer an issue for the developed world, developing countries may still face food scarcity as the demand for cash crops means a loss of land available for subsistence farming. The concentration of power in the hands of a small number of global food outlets, such as McDonalds, has been blamed for contributing to an increase in unhealthy diets and the loss of home grown and home cooked products.

Globalization therefore has ambiguous effects on national goals for healthy eating. While the 5-a-day programme is facilitated by the year-long availability of fruit and vegetables, the increased reliance on manufactured and pre-cooked food with high levels of sugar, salt and saturated fats contributes to the rise of obesity and associated health problems. Yeatman (2003) argues that local food projects such as community gardens or lunch clubs are popular with local practitioners but marginal to mainstream political concerns. Local projects are acceptable and serve to divert interest away from significant issues such as the influence of global commercial food companies. Globalization has more negative effects on developing countries, for while it may foster economic growth and trade, local capacity to feed people may be lost.

The public policy environment inevitably involves struggles for power and influence in which politicians, civil servants, the media and pressure groups may try to achieve their preferred ends. One problem with public health policy is that it is not usually seen as being newsworthy. Long-term investments in health which prevent illness or disability are not as attractive to the media as topical scandals or ‘feel-good’ stories focused on high technology medical services and individual patients. For example, the coverage of the introduction of congestion charging in London, intended as a public health measure to reduce car use, has focused on local objections to the extra ‘taxation’ and stories of the effect on livelihoods. An exception to this type of coverage is the resurgence of interest in public health protection and hazard management in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the USA in 2001 and the war in Iraq in 2003.

Baum (2001) has shown how power is exercised in various ways and how the decision-making process can be manipulated so that certain issues are not even raised. In Australia the professional medical lobby and the private health insurance lobby are so powerful that they can ensure that the concept of an exclusively public health insurance scheme is not raised. In other cases, powerful stakeholder groups may present arguments that tap into popular sentiments and lobby support for resisting public health measures.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access