Chapter 3 The perioperative environment

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Introduction

The perioperative environment is a specially designed and regulated area that plays a significant role in patient safety during the surgical procedure. Incorporating special design features, such as positive pressure air conditioning, traffic patterns to restrict entry of contaminants from external sources of the hospital, easy-to-clean floor and wall surfaces, and electrical safety controls, all contribute to reduce the risk of infection to the surgical patient (Queensland Health, 2002). Safety features related to electrical equipment, radiation and laser further protect both patients and staff from hazards inherent in a highly technical environment.

Operating suite design and layout

The operating suite design and layout must accommodate the day-to-day workload and the corresponding fluctuations in staff and patient numbers (Centre for Health Assets Australasia [CHAA], 2006). The operating suite is an environmentally controlled unit consisting of many distinct functional areas. It may be adjacent to a preadmission area (or perioperative unit), through which patients for day surgery and those who will be admitted for longer stays are admitted.

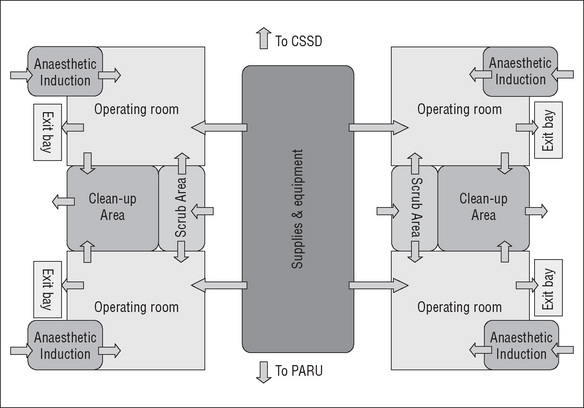

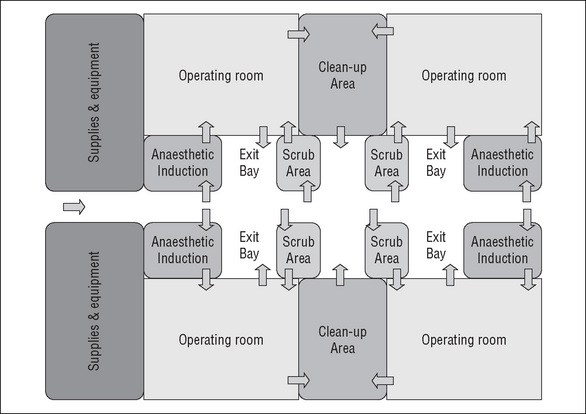

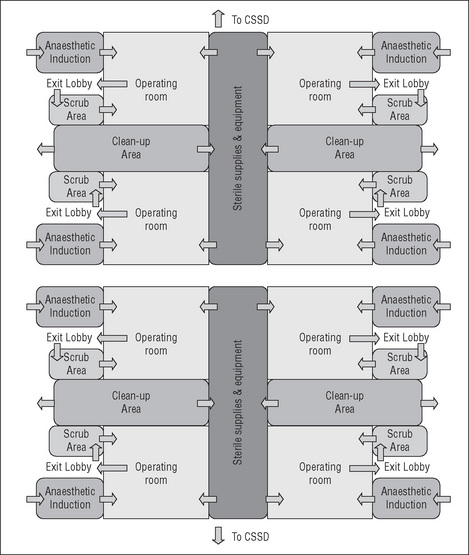

When designing the operating suite, the decision regarding the number of operating rooms and recovery spaces is governed by many factors, including the number, type and complexity of surgical procedures to be undertaken and the number of postoperative beds available. There are several design models for the operating suite layout that achieve a balance between the environmental needs of the staff, infection control, operational flow and functional requirements (CHAA, 2006).

Every Australian state and territory and New Zealand have their own set of building codes, infection control guidelines and capital works guidelines to assist with hospital design when new hospitals are being planned or refurbishments are being undertaken (Carthey, 2006). Australasian Health Facility guidelines were released in 2006 to assist Australian and New Zealand health departments undertaking health facility projects to achieve the standards for building, space, equipment, fit out and furnishings, and are the minimum standard for design (Carthey, 2007).

Some of the planning models for the operating suite include the following:

The operating suite should have close or direct links with other units for convenience, patient safety and practicality (CHAA, 2006). These units include the:

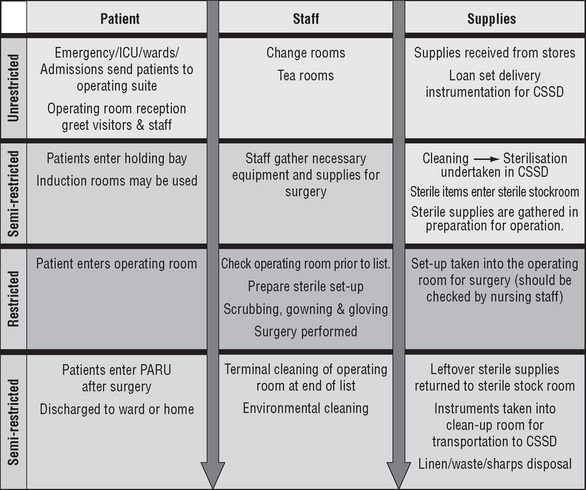

Traffic patterns

Traffic patterns are established to define movement throughout the operating suite for personnel, equipment, supplies and instrumentation, and to prevent contact from sources

of potential contamination. Ideally, waste, contaminated supplies and soiled instruments should not travel down the same corridor as clean and sterile supplies. However, if this is necessary due to the suite’s design, then measures must be undertaken to minimise any potential contamination of clean with dirty supplies (CHAA, 2006). Such a method could include using a sealed ‘closed cart’ system for transporting soiled and contaminated items to the sterilising department for decontamination.

Operating suite layout

Unrestricted areas

Preoperative holding bay

In the unrestricted areas there is unlimited access to all personnel, who may wear either perioperative attire or street clothes. The preoperative holding bay is a waiting area for patients prior to surgery where admission procedures, such as patient identification checks, are carried out, all documentation is confirmed and the responsibility for the patient is handed over by the ward or perioperative unit staff to perioperative nurses. A nurse is usually assigned to work in this area to monitor the patients’ condition and to help coordinate each operating room’s schedule by calling for patients from the wards/ perioperative unit in a timely manner to minimise delays (ACORN, 2006a).

Semi-restricted areas

Sterile stock room

Areas for storing wrapped, sterile supplies must be easily accessible from all operating rooms and may be contained in a central location. Sterile packages and trays are ideally stored on open wire shelving at least 250 mm above the floor and 440 mm from the ceiling. The open shelving allows dust to fall to the floor and permits cleaning to take place more effectively (ACORN, 2006f; Standards Australia, 2003, AS/NZS 4187).

To maximise storage space, many operating suites use mobile compactors. The sterile stock room must be kept cool and dry, with a temperature of 22–24°C and a relative humidity of 35–68% to prevent compromising the integrity of the sterile packages (ACORN 2006f). Sterile supplies need to be kept away from direct sunlight and, therefore, windows within this sterile stock area are not considered ideal (Standards Australia, 2003, AS/NZS 4187). The sterile stock room needs to be cleaned regularly and kept free of dust, vermin and insects (ACORN, 2006f).

Postanaesthesia recovery unit

The PARU can also be classified as a semi-restricted area; however, the wearing of perioperative attire is at the discretion of each hospital or facility (ACORN, 2006c). As well as perioperative staff, it needs to be accessible to medical and other staff wearing street clothes in the event of an emergency (Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, 2006).

In the PARU, patients who have undergone anaesthesia and/or surgery are provided care, so the PARU needs to be located close to the operating/procedure rooms. The layout and design of the PARU needs to allow for good observation of all patients simultaneously and especially from the staff station when required. Curtained cubicles may allow privacy for patients while still maintaining a wide space, as private rooms are inappropriate in the PARU (CHAA, 2006).

Sterilising department

The sterilising department’s largest client will always be the operating suite and, therefore, it must be located within easy access to facilitate the passage of clean and dirty instruments between the two departments. Enclosed carts or containers with lids should be used to transport contaminated instruments to the sterilising department, and separate clean and dirty elevators should be used to transport instruments to and from the sterilising department if it is located on a different floor to the operating suite (CHAA, 2006).

Restricted areas

Usually accessed from a semi-restricted area, the restricted areas include procedure and operating rooms, where staff must wear surgical attire and personal protective equipment (ACORN, 2006b).

Operating rooms

The minimum size recommended for a general operating room is 42 square metres, whereas a large operating room (usually designated for cardiac, neurosurgery, orthopaedic joint or transplantation surgery) is 52 square metres (CHAA, 2006).

Dedicated operating rooms

Some hospitals, particularly larger tertiary hospitals, dedicate operating rooms to specialty surgery (e.g. neurosurgery, orthopaedic surgery). This is beneficial as it allows specialized equipment, such as microscopes and special operating room tables, to remain within the operating room, reducing the potential for damage due to movement, although fixed equipment may limit the flexibility of the operating room in smaller suites (ACORN, 2006b; CHAA 2006).

Integrated operating rooms

and down the table to capture X-ray images anywhere along the length of the body. To accommodate the extra equipment and technology, the integrated operating room is usually double the size of a standard operating room, at about 80 square metres. With the increase in minimally invasive surgery, these highly specialised settings are likely to become the operating room of the future (Phillips, 2007).

Scrub areas

Scrub areas (or bays) provide sinks with running water and access to antiseptic solutions to accommodate several members of the surgical team undertaking the surgical scrub procedure simultaneously. To facilitate adherence to aseptic technique, these sinks need to be located directly outside the operating room to allow easy access to sterile gown and glove trolleys, which may be located in the scrub bay itself or within the operating room. To prevent slip injuries, the floor coverings in the scrub areas should be of a non-slip texture (CHAA, 2006).

Design features of the operating suite

Windows

Staff morale is always boosted by natural light, and having windows within the operating suite is recommended (ACORN, 2006b). However, it is not always practical to have windows in the operating room itself, where procedures such as minimally invasive surgery may require a darkened theatre to maximise the visual image on the screen. Also, when lasers are used, appropriate protective window coverings within the operating room must be provided (Queensland Health, 2002).

Ceilings, doors, floors and walls

Ceilings within the perioperative environment should be made of a non-reflective, non-porous material without cracks or open joins that permit the accumulation of dirt and are difficult to clean. Light fittings must be flush fitting and sealed to inhibit any dust or dirt entering the environment (CHAA, 2006). Swing-type doors for the operating room allow easy access for hands-free entry (Abreu & Potter, 2001). Consideration should be given to fitting the lower section of the door (from the floor edge up to 150 mm) with a thin layer of aluminium to protect it from constant battering and wetness due to frequent floor mopping. Floors are generally made of seamless vinyl that is impervious to moisture, easily cleaned, stain resistant, comfortable for long periods of standing and suitable for wheeled traffic (CHAA, 2006). Walls are also made of seamless vinyl and curved where they meet the floor to assist in effective cleaning. The colour should be neutral with a matt or satin finish to reduce glare, which can be disturbing to the surgical team (Gruendemann & Mangum, 2001). Tiles, once a popular wall covering, are no longer considered a suitable finish within an operating room due to the potential for cracking, which poses infection control risks (CHAA, 2006). Due to the high traffic of trolleys in the unit, damage to walls and doors is inevitable and, therefore, consideration should be given for wall and corner protection (CHAA, 2006).

Other features of the operating suite

The operating suite utilises many features to create and maintain a safe, clean environment for patients. These measures include the ability to set parameters for temperature, humidity and ventilation systems.

Temperature

The temperature range within the operating suite should be 18–24°C. Individual operating rooms should have a temperature range of 20–22°C; this temperature range inhibits bacterial growth and is tolerated well by both staff and patients (Gruendemann & Mangum, 2001). However, the temperature may require adjusting to accommodate some types of surgery and/or the condition of individual patients. For example, burns or paediatric patients require higher ambient temperatures as these patients are highly susceptible to hypothermia. In contrast, some types of neurosurgical patients require a much cooler environment.

Humidity

The humidity in the operating room should be maintained at 50–60% to both inhibit bacterial growth and decrease risks associated with static electricity. Additionally, high humidity can increase fatigue among the surgical team and is thus best avoided (ACORN, 2006b; Rothrock, 2007).

Ventilation

Air-conditioning systems within the operating suite use positive pressure, which pushes air down from within the operating suite and out into the external environment. Positive air pressure is greater in the operating room than the surrounding corridors and scrub areas, with the exception of the sterile stock room, which has the same air pressure as inside the operating room (Queensland Health, 2002). This positive pressure forces air from the operating room out into the corridors, resulting in the air in the outer corridors having a higher microbial count. For this reason, operating room doors must be kept closed at all times (other than the necessary passage of staff, supplies and the patient) to reduce the risk of airborne contaminants entering the surgical field. The microbial count within the individual operating room is usually at its peak during the time of the skin incision because this follows a period of maximum air disturbance created by staff gloving and gowning, patient draping, the movement of operating room staff and the frequent opening and closing of the operating room doors. Because the microbial count rises every time the operating room doors are opened, it is necessary to ensure all required supplies are readily at hand (within the operating room, generally) during the course of any surgical procedure (Phillips, 2007; Woodhead & Wicker, 2005).

Electrical safety

All electrical equipment must be checked by the hospital’s biomedical engineering department prior to installation and, thereafter, at regular intervals to ensure they are functioning safely and meet national standards. Staff should check each piece of electrical equipment prior to use to ensure correct functioning, including inspection of electrical cords for any damage. Extension cords are not used within operating rooms due to the danger they pose to patients—of accidental dislodgement—and the occupational health and safety risk for staff, who may trip over the cords (Standards Australia, 2004a, AS/NZS 2500).

There are two main types of electrical shock against which staff and patients must be protected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree