Chapter 1. The Nursing Process

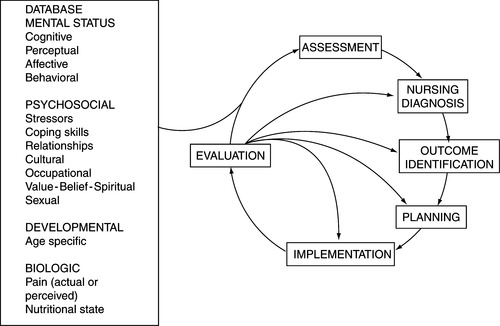

The time-tested nursing process continues to guide nurses and other disciplines in clinical practice. The nursing process, in theory, is a multistep problem-solving method in which client problems and needs are assessed, diagnosed, treated, and resolved in an orderly fashion. The nursing process, in practice, is a more cyclic approach because of the client’s changing responses to health and illness. Because the client’s condition is dynamic rather than static, the nurse uses the steps of the nursing process interchangeably and continuously, according to the client’s responses on the health-illness continuum. Assessment is ongoing. For example, it takes place initially; identifies the client’s obvious needs and problems; and continues throughout the planning, intervention, and evaluation phases of the nursing process (Figure 1-1). The assessment database expands as the client manifests other needs and problems. A client can be an individual, a family, a group, or a community.

Psychiatric–mental health nursing practice presents a unique and exciting challenge for health professionals using the nursing process. The client’s responses to mental and emotional illness are demonstrated through cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains, all of which are dynamic and subject to change. The nurse also evaluates more constant areas, such as the client’s culture, ethnicity, spirituality, sexuality, and developmental level. The psychiatric nurse focuses primarily on the client’s psychosocial needs; however, the client’s physical status and reports of pain or discomfort are also evaluated. The nursing process is also used to help psychiatric–mental health nurses make sound clinical judgments. The critical role of the nursing process as a theoretic framework is supported by the American Nurses’ Association’s Scope and Standards of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Practice (revised 2000).

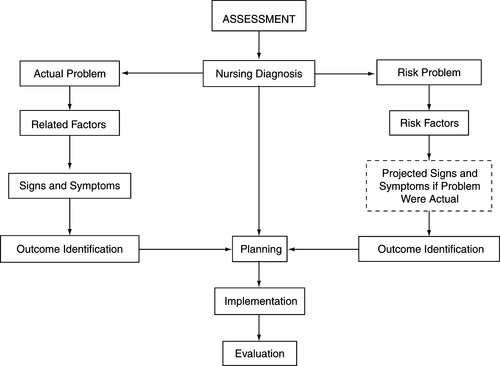

The steps of the nursing process are contained in Box 1-1. Figure 1-2 details the nursing process in actual and risk problems.

BOX 1-1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

▪ Assessment

▪ Nursing diagnosis

▪ Outcome identification

▪ Planning

▪ Implementation

▪ Evaluation

|

| Figure 1-2 |

ASSESSMENT

Assessment, the first step of the nursing process, provides the nurse with relevant data from which nursing diagnoses, the focus of treatment planning, are developed. Throughout the assessment phase, the psychiatric nurse collects data through learned interactive and interviewing skills and observations of the client’s behaviors and the client’s reports of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions. The nurse’s assessment skills are based on a broad biopsychosocial background and knowledge of normal and dysfunctional behaviors, which are grounded in relevant research (evidence based practice). In the discipline of psychiatric–mental health nursing, assessment takes place in many settings within the milieu. The nurse, therefore, has several opportunities to observe the client and modify assessment data according to the client’s continued adjustment to the milieu, as well as observe the client’s progress throughout hospitalization.

Ideally, the client provides information during the assessment phase, although data may also be obtained through client records, family, other staff, and physicians. If the client is unable to offer a complete or accurate health history, a reliable person may be interviewed on the client’s behalf, with the understanding that such information will be evaluated in terms of that person’s relationship with the client.

Areas of psychiatric nursing assessment are:

▪ Physical (including pain and comfort levels)

▪ Psychiatric/psychosocial

▪ Developmental

▪ Family dynamics

▪ Cultural

▪ Spiritual

▪ Sexual

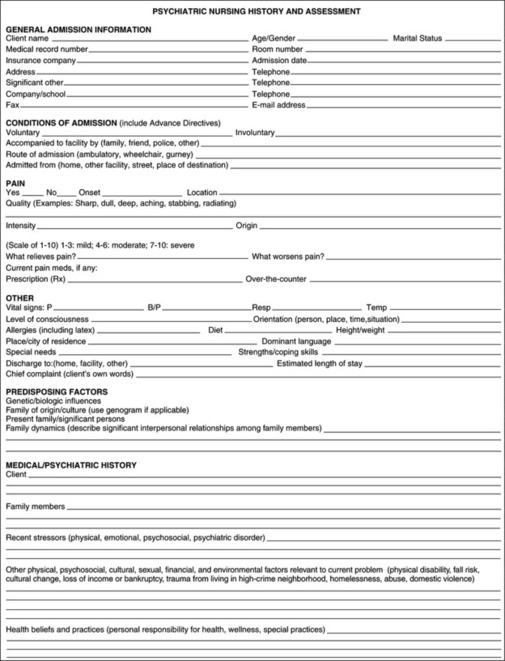

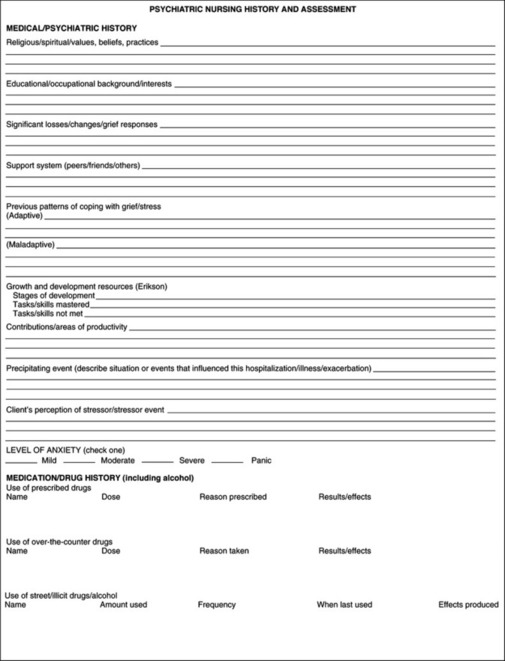

The method of assessment includes the client’s subjective reporting of symptoms and problems and the nurse’s objective findings (Figure 1-3).

Assessment of Mental Status

The mental status examination is the psychiatric–mental health component of client assessment. It is the basis for medical and nursing diagnoses and management of client care. The mental status examination is an organized collection of data that reflects an individual’s functioning on many levels at the time of the interview, such as appearance, behavior, and attitude (Box 1-2).

BOX 1-2

MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION

Appearance

Dress, grooming, hygiene, cosmetics, apparent age, posture, facial expression

Behavior/Activity

Hypoactivity or hyperactivity; rigid, relaxed, restless, or agitated motor movements; gait and coordination; facial grimacing; gestures; mannerisms: passive, combative, bizarre, odd, eccentric

Attitude

Interactions with interviewer: cooperative, resistive, friendly, hostile, ingratiating

Speech

Quantity: poverty of speech, poverty of content, voluminous

Quality: articulate, congruent, monotonous, talkative, repetitious, spontaneous, circumlocutory, tangential, confabulating, pressured, stereotypical

Rate: slowed, rapid, normal

Mood and Affect

Mood (intensity, depth, duration): sad, fearful, depressed, angry, anxious, ambivalent, happy, ecstatic, grandiose

Affect (intensity, depth, duration): appropriate, apathetic, sad, constricted, blunted, flat, labile, euphoric, bizarre

Perceptions

Hallucinations, illusions, depersonalization, derealization, distortions

Thoughts

Form and content: logical vs. illogical, loose associations, flight of ideas, autistic, blocking, broadcasting, neologisms, “word salad,” obsessions, ruminations, delusions, abstract vs. concrete

Sensorium/Cognition

Levels of consciousness, orientation, attention span, recent and remote memory, concentration; ability to comprehend and process information; intelligence

Judgment

Ability to assess and evaluate situations, make rational decisions, understand consequences of behavior, and take responsibility for actions

Insight

Ability to perceive and understand the cause and nature of own and others’ situations (e.g., understands own mental illness)

PSYCHOSOCIAL CRITERIA

Stressors

Internal: psychiatric or medical illness; perceived loss, such as loss of self-concept/self-esteem

External: actual loss, such as death of a loved one, divorce, lack of support systems, job or financial loss, retirement, or dysfunctional family system

Coping Skills

Adaptation to internal and external stressors; use of functional, adaptive coping mechanisms and techniques; management of activities of daily living; ability to solve basic life problems

Relationships

Attainment and maintenance of satisfying interpersonal relationships consistent with developmental stage; includes sexual relationship as appropriate for age and status

Reliability

Interviewer’s impression that individual reported information accurately and completely

Cultural

Ability to adapt and conform to prescribed norms, rules, ethics, and mores of an identified group

Spiritual (Value-Belief)

Presence of a self-satisfying value-belief system or religion that the individual regards as right, desirable, worthwhile, and comforting

Occupational

Engagement in useful, rewarding activity, congruent with developmental stage and societal standards (work, school, recreation)

The other major focus of the mental status examination is the psychosocial criteria and stressors that help define the client’s strengths and capabilities for interacting with the environment. These include the ability to initiate and sustain meaningful relationships and to achieve satisfaction consistent with one’s sociocultural lifestyle (see Box 1-2). Knowledge of the psychodynamics and psychopathology of human behavior is necessary in assessing the client’s adjustment or maladjustment to internal and external life stressors.

The Interview

The client assessment interview, or intake interview, is essential in gathering critical information about the client’s overall health status. It is a more meaningful, flexible method of collecting data than questionnaires or computers. The interview allows the nurse to use all the senses to explore the client’s behavior, as well as specific topics and concerns. The assessment interview can take place in many settings other than the mental health facility, including the admissions/intake office, emergency department, medical-surgical unit, skilled nursing facility, crisis house, community center, alcohol/drug rehabilitation program, therapist’s office, school, home, or prison.

In the mental status assessment, the primary evaluation tool is the nurse interviewer. The success of the interview depends on the development of trust, rapport, and respect between the nurse and the client. The nurse uses essential time-tested interpersonal techniques and communication skills, such as appropriate use of silence, reflective questioning, and offering general leads, to interact with the client and family in a therapeutic manner throughout the interview (see Table 1-1). The therapeutic qualities of the nurse are essential ingredients of the nursing process as the nurse assesses, diagnoses, and plans treatment for the client and family.

| Therapeutic Technique | Examples |

|---|---|

| Using silence | |

| Giving recognition or acknowledging | “Yes, that must have been difficult for you.” |

| “I noticed that you’ve made your bed.” | |

| Offering self | “I’ll walk with you for a while.” |

| Giving broad openings or asking open-ended questions | “Is there something you’d like to do?” |

| “How do you feel about that?” | |

| Offering general leads or “door openers” | Nodding one’s head occasionally to show interest. |

| “Go on.” | |

| “You were saying…?” | |

| Placing the event in time or in sequence | “When did your nervousness begin?” |

| “What happened just before you came to the hospital?” | |

| Making observations | “I notice that you’re trembling.” |

| “You seem to be angry.” | |

| Encouraging description of perceptions | “What does the voice that you hear seem to be saying?” |

| “How do you feel when you take your medication?” | |

| Encouraging comparison | “Has this ever happened before?” |

| “What does this resemble?” | |

| Restating | Client: I can’t sleep. I stay awake all night. |

| Nurse: You can’t sleep at night. | |

| Reflecting | Client: I think I should take my medication. |

| Nurse: You think you should take your medication? | |

| Focusing on specifics | “This topic seems worth discussing in more depth.” |

| “Give me an example of what you mean.” | |

| Exploring | “Tell me more about your job. Would you describe your responsibilities?” |

| Giving information or informing | “Her name is Dr. Jones, and she is a psychiatrist.” |

| “I’m going with you on the field trip, as I promised.” | |

| Clarifying or seeking clarification | “I’m not sure that I understand what you are saying. Please give me more information.” |

| Presenting reality or confrontation | “I see no strangers or spies in the room. These people are all patients or hospital staff.” |

| “This is a hospital, and you are a patient here. And I am a nurse.” | |

| Voicing doubt | “I find that hard to believe. Did it happen just as you said?” |

| Encouraging evaluation or evaluating | “Describe how you feel about taking your medication.” |

| “Does participating in group therapy help you discuss your feelings?” | |

| Attempting to translate into feelings or verbalizing the implied | Client: I’m empty and numb. |

| Nurse: Are you saying that you’re not feeling anything right now, or you’re not sure of your feelings? | |

| Suggesting collaboration | “Perhaps you and your social worker can work together to plan your living arrangements after your discharge.” |

| Summarizing | “During the past hour we talked about your plans for the future. They include the following.” |

| Encouraging formulation of a plan of action | “If this situation occurs again, what options do you have?” |

| Asking direct questions | “How do you feel about your hospitalization?” |

| “How do you see your progress?” | |

Essential Qualities for a Therapeutic Relationship

▪ Genuineness. The nurse achieves validity with the client through sincerity, verbal and behavioral congruence, and authenticity. The nurse supports words with appropriate actions as long as it benefits the client. The nurse is able to meet the client’s needs, but not necessarily fulfill the client’s demands. For example, “I will meet with you tomorrow as we planned, but I won’t bring you cigarettes.” Genuineness does not mean “baring one’s soul” or sharing personal problems; the client does not need further burdens.

▪ Respect. Unconditional positive regard, nonpossessive warmth, consistency, and active listening earn the nurse respect from the client. The nurse keeps appointments, shows up on time, and listens respectfully to the client’s concerns while respecting the client’s space and privacy.

▪ Empathy. The nurse views the world through the client’s eyes but remains objective. The nurse does not identify, agree, or overly sympathize with the client but is able to focus on the client’s feelings and not view the client as a stereotypic, textbook figure.

▪ Concreteness/specificity. The nurse speaks in realistic, literal terms versus vague, theoretic concepts. Clients with psychiatric disorders may have problems interpreting concepts.

▪ Self-disclosure. Appropriate disclosure of a view of one’s attitudes, feelings, and beliefs can be useful in the nurse-client relationship. Role-modeling some shared experiences helps the client to reveal self, become more open, and feel more secure. The nurse may share feelings only when it is clear that the client will benefit from them. For example, “I have also been angry at times. Tell me how you usually manage your anger.”

▪ Confrontation. The nurse approaches the client in a direct manner, usually because of perceived discrepancies in the client’s behavior. Confrontation is used to help the client develop an awareness of incongruent behavior. For example, a client may say he will attend therapeutic group sessions, then not show up for group without a good reason. The nurse confronts the client by pointing out this inconsistent behavior. Confrontation needs to be done in an accepting, nonthreatening manner and only after rapport has been established.

▪ Immediacy of the relationship. The nurse focuses on the nurse-client interaction as a typical way in which the client may relate to others. The nurse needs to be careful not to share too many spontaneous feelings all at once, because divulging too many negative or personal experiences may be detrimental to the relationship, especially at the beginning.

▪ Self-exploration. The nurse helps the client vent and explore feelings during appropriate times throughout the interaction. Self-exploration may serve as a catharsis.

▪ Role-playing. The nurse helps the client act out a particular event, situation, or problem to help the client gain understanding. Role-playing may also be cathartic.

Principles of a Therapeutic Nurse-Client Relationship

1. Continually evaluate the client’s risk for suicide using principles of suicide assessment (see Box 3-6).

3. Develop an awareness of own feelings, fears, and biases regarding clients with mental disorders (autodiagnosis).

4. Discuss own fears and concerns with qualified peers.

5. Speak to the client in a moderate tone of voice, using a calm “matter-of-fact” approach and nonjudgmental attitude. Refrain from extremes of expression or responses that indicate surprise or disbelief.

6. Continue to develop trust and rapport with the client through shared time and support during the day. Use brief one-to-one contacts rather than lengthy, drawn-out conversations.

7. Remain quietly with the depressed or withdrawn client who is unable to engage in conversation at first.

8. Allow sufficient time for the client to respond, while assessing the client’s ability to tolerate silence and presence of the nurse. Do not prolong the contact if the client is obviously uncomfortable or resistant, unless the client is troubled or suicidal and cannot be left alone.

9. Individualize the client’s needs throughout contact to acknowledge the client’s value and worth.

The Nurse-Client Relationship

The nurse-client relationship is therapeutic, not social, in nature. It is always client centered and goal directed. It is objective rather than subjective. The intent of a professional relationship is for client behavior to change. It is a limited relationship, with the goal of helping the client find more satisfying behavior patterns and coping strategies and increasing self-worth. It is not for mutual satisfaction, although the nurse may benefit from the client’s positive outcome.

In the preorientation phase, the nurse gathers data about the client and the client’s situation and condition (chart, staff, physician). The nurse also uses the process of autodiagnosis (self-diagnosis) to determine his or her own perceptions, possible biases, and attitudes about the client. A commitment to nonjudgmentalism and the avoidance of stereotyping are imperative.

Autodiagnosis

Questions that nurses ask themselves during the self-diagnosis process (autodiagnosis) include the following:

▪ Do I label clients with the stereotype as a group?

▪ Is my need to be liked so great that I become angry or hurt when a client is rude, hostile, or uncooperative?

▪ Am I afraid of the responsibility I must assume in this relationship? (This fear may decrease the nurse’s independent functions.)

▪ Do I cover feelings of inferiority with an air of superiority?

▪ Do I require sympathy and protection so much myself that I drown my clients with it as well?

▪ Do I fear closeness or identifying myself with the client to the extent of being cold and indifferent?

▪ Do I need to feel important and keep clients dependent on me?

Orientation Phase

The purposes of the orientation phase are to become acquainted with the client, gain rapport, demonstrate genuine caring and understanding, and establish trust. The orientation phase usually lasts 2 to 10 sessions but with some clients it can take many months (Box 1-3). With the current shorter lengths of stay, the phases of the relationship may not be as clear and distinct, and the nurse needs to use all the therapeutic resources to establish trust and rapport in a timely manner. Guidelines and steps in the orientation phase are as follows:

BOX 1-3

▪ The client may willingly engage in a therapeutic relationship.

▪ The client may test the nurse and the limits of the nurse-client relationship by:

□ Being late for meetings

□ Ending meetings early

□ Playing the nurse against the staff

▪ The client may not remember the nurse’s name or appointment time.

□ The nurse puts information on a card and gives this to the client.

□ The nurse reinforces contract in early meetings and restates limits if necessary.

▪ The client may attempt to shock the nurse by:

□ Using profane words

□ Sharing an experience that the client believes will shock or frighten the nurse

□ Using bizarre behavior

▪ The client may focus on the nurse in an attempt to see if the nurse is competent.

□ The nurse refocuses on the client.

1. Build trust and security (first step in any interpersonal experience).

a. Establish contract.

b. Be dependable; follow contract, and keep appointments.

c. Allow client to be responsible for contract.

e. Show caring and interest.

f. When a client is unable to control behavior, set limits, and provide appropriate alternative outlets (see Box 1-3).

2. Discuss the contract: dates, times, and place of meetings; duration of each meeting; purpose of meetings; roles of both client and nurse; use of information obtained; and arrangements for notifying client/nurse if unable to keep an appointment.

3. Facilitate the client’s ability to verbalize his or her problem.

4. Be aware of themes.

a. Content: What the client is saying.

b. Process: How the client interacts.

c. Mood: For example, hopeless or anxious.

d. Interaction: For example, did the client ignore you? Was the client submissive? Did the client dominate the conversation?

5. Observe and assess the client’s strengths, limitations, and problem areas. Build on client’s strengths and positive aspects of personality. Include the client in identification of client’s attributes.

6. Identify client problems, nursing diagnosis, outcome criteria, and nursing interventions. Formulate nursing care plan.

Working Phase

The working phase ideally begins when the client assumes responsibility to uphold the limits of the relationship. Adjustments may have to be made, depending on the client’s length of stay. The purpose of the working phase is to bring about positive changes in the client’s behavior, with focus on the “here and now” (Box 1-4). To achieve this, set priorities when determining the client’s needs, as follows:

BOX 1-4

The client may:

▪ Use less testing, less focusing on the nurse, and fewer attempts to shock the nurse.

▪ Remember and anticipate appointment with the nurse.

▪ Use more description and clarification to facilitate understanding; wants the nurse to know how the client feels.

▪ Be more responsive in interactions.

▪ Improve appearance.

▪ Bring up topic that the client wants to discuss.

▪ Confide more confidential material.

*The working phase is painful for the client and is reached when change occurs as the client and the nurse evaluate and discuss the client’s problems.

1. Preserve the client’s life and safety. Is the client suicidal, not eating, smoking in bed while medicated, or acting out behavior that could be harmful to others?

2. Modify behavior that is unacceptable to others (e.g., acting out or hostile verbalization, bizarre behavior, withdrawal, poor hygiene, inadequate social skills).

3. Identify with the client those behaviors that the client is willing to change; set realistic goals. Make goals testable and attainable for successful experiences. This will increase the client’s sense of self-worth and will help the client to accept the need for growth.

Termination Phase

The purpose of the termination phase is to dissolve the relationship and assure the client that he or she can be independent in some or all of his or her functioning.

Ideally, the termination phase begins during the orientation phase. The more dependent and involved relationships may require a longer time for termination. Termination normally occurs when the client has improved sufficiently for the relationship to end, but it may occur if a client is transferred or you leave the facility (Box 1-5).

BOX 1-5

The client may:

▪ Deny separation.

▪ Deny significance of relationship/separation.

▪ Express anger or hostility (overtly or covertly). Anger, openly expressed to the nurse, may be a natural and healthy response to an event. The client feels secure enough to show anger. Nurse responds in accepting, neutral manner.

▪ Display marked change in attitude toward the nurse/therapist; may make critical remarks about the nurse or be hostile because of pending break of emotional ties. If the nurse does not understand the reason for the client’s reaction, the client may react with anger or defensiveness and block the termination process.

▪ Display a type of grief reaction. It takes time to accept the loss, which is why it is important to start the termination process early.

▪ Feel rejected and experience increased negative self-concept.

▪ Terminate relationship prematurely.

▪ Regress to exhibition of previous symptoms.

▪ Request premature discharge.

▪ Make a suicide attempt.

▪ Be accepting but still express regret or feel momentary resentment. This is a healthy response. Make a clean break, or you may hinder the client’s realization that relationships often must, and do, terminate.

Methods of Decreasing Involvement

1. Space your contacts further apart (not usually necessary in student clinical experience).

2. Reduce the usual length of time you spend with the client (may not be necessary in brief lengths of stay).

3. Change the emotional tone of the interactions.

a. Do not respond to or follow up on clues that lead to new areas to investigate (but alert staff if this occurs).

b. Focus on future-oriented material.

4. Some clients may want to continue working up to the last meeting; use your judgment.

What to Discuss With Client About Termination

1. Help the client discuss his or her feelings about termination.

2. Have the client talk about gains he or she has made (include negative aspects of sessions as well).

3. Share with the client the growth you see in the client.

4. Express benefits you have gained from the experience.

5. Express your feelings about leaving the client (be sure to keep your emotions in check).

6. Never give the client your address or telephone number.

Impasses That Obstruct a Therapeutic Relationship

▪ Resistance. The client is reluctant to divulge information about self because he or she doubts ability to be helped. Unconditional acceptance and persistence by the nurse are critical.

▪ Transference. The client views the nurse as a significant person in the client’s life and transfers feelings, emotions, and attitudes felt for that person onto the nurse. The nurse may need assistance to deal with transference issues. Clarification of the nurse-client relationship is imperative during this time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access