Introduction

Pregnancy is a natural phenomenon and is very much influenced by the wider social context in which the mother, baby and family live. Midwives are uniquely placed to influence the health and well-being of women during their childbearing experience and as such, all midwives have a role in understanding the importance of preventing illness and disease, whilst promoting health and well-being by providing high-quality evidence-based care. Women and babies should be as well, if not fitter and healthier, after pregnancy and birth as they were before.

Although geopolitically, the UK is regarded as a single entity, healthcare systems and management vary across the four countries, and where possible the authors have made such distinctions.

Public health has been defined as being ‘about helping people to stay healthy and avoid getting ill’ (DH 2012a). This includes specific areas such as nutrition, recreational substance use (licit and illicit), sexual health, pregnancy, immunisation and children’s health. The main concerns of public health are twofold: the health of populations and the health of individuals or groups within a population. Population health needs are embraced within overarching measures such as food and water safety, road safety and the provision of free at point of care health services. These are applied to the whole population, with standards often enshrined in legislation, and monitored through non-departmental public bodies such as the Environment Agency or the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in England.

Much public health activity in the UK is derived from government, and the drivers are both political and economic, as the burden of disease is costly to a nation in which the state subsidises health and social care. A new structure, Public Health England, introduced in April 2013, has the remit to protect public health by delivering on the objectives of the Public Health Outcomes Framework (DH 2011a, 2012b). The Health & Social Care Act 2012 is the legislation responsible for this; at national level, Public Health England will be the executive agency responsible for delivering the wider agenda, whilst at local level, the move of public health services into local authorities is planned to create a multiprofessional approach to delivering local strategies to support better healthcare for the population.

Epidemiology is a further useful concept for the midwife to understand. The World Health Organization (WHO 2012a) defines it as ‘the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events’. It focuses on understanding health risks and the spread of disease within and beyond specific populations. The Health Protection Agency (HPA), an independent body, undertakes health surveillance on behalf of the government in England, and its main concern is communicable diseases, where the HPA gathers data on the incidence of a range of infections such as gastrointestinal, healthcare-associated (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA) and blood-borne diseases such as HIV. The HPA monitors the incidence of vaccine-preventable infections such as measles and whooping cough. It also gathers data on environmental problems such as chemical hazards and poisons. The HPA has now become part of Public Health England.

In England, under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010, some diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) and measles have to be notified to local authority proper officers (HPA 2012a). Public Health Wales, Health Protection Scotland and Health & Social Care Northern Ireland have very similar arrangements for notifying diseases which present a particular risk. This information is used to alert authorities to the risk of disease outbreaks which threaten public health and may demand a rapid response, and to monitor trends in communicable diseases. The list changes from time to time; for example, from 2010 ophthalmia neonatorum is no longer a notifiable disease (HPA 2012a).

New initiatives are introduced as evidence becomes available. For example, an increase in whooping cough (1230 cases reported up to August 2012 in England and Wales, which included nine deaths, compared to only 910 cases during the whole of 2011 (HPA 2012b) prompted the DH (DH 2012c) to initiate a short-term immunisation programme to reduce the spread of whooping cough, commencing in October 2012. This is administered during the third trimester of pregnancy to boost the short-term immunity passed on by pregnant women to protect their newborn, who normally cannot be vaccinated until they are 2 months old.

The health of the population is influenced by personal/lifestyle choices and by environmental factors, such as living conditions, type (or absence) of work, diet and exposure to toxins. Midwives working in the community are aware of inequalities in health and sometimes find that there are areas of affluence, with better health outcomes, close to areas of deprivation.

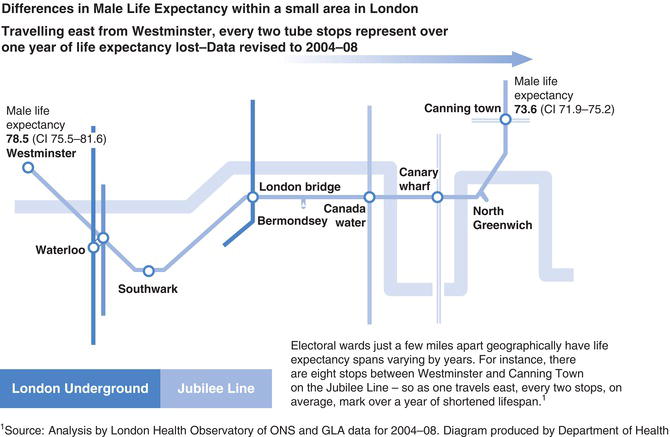

Figure 12.1 The Jubilee Line of health inequality.

Source: London Health Observatory (2010), reproduced with permission.

The London Health Observatory has produced a vivid image illustrating this, where the measure is life expectancy (Figure 12.1). Although the map refers to males, female life expectancy follows a similar trend, with a range of 84.2–80.6 years, travelling east along the same line between the same ‘stations’ as the male (Ball & Tewdwr-Jones 2012). Health outcomes in urban areas are strongly determined by social and economic inequality, the assertion here being that travelling east from the more affluent areas sees a reduction in the health and well-being of the population. This pattern is not peculiar to London and the same trends may be observed across the UK, with life expectancy generally lower in urban and deprived areas (Kyte & Wells 2010).

Mortality and morbidity

Maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity are part of the measurement used to assess how well (or not) a health service is performing. Maternal mortality can be defined as the number of deaths during pregnancy or within 42 days after the end of pregnancy, regardless of the gestation. It is usually expressed as the number of deaths per 100,000 maternities. Maternal deaths are classed as direct, that is, resulting directly from complications arising during the pregnancy, labour or puerperium. Examples are deaths from haemorrhage or pre-eclampsia. Indirect deaths result from a pre-existing disorder which has been made worse by the pregnancy, for example cardiac disease. Late deaths are those which occur more than 42 days (but less than 1 year) after the end of the pregnancy, due to direct or indirect causes, and coincidental deaths are deaths from causes not related to pregnancy or birth, but where death happened to occur during the childbearing period (CMACE 2011). Perinatal mortality includes all stillbirths and deaths within the first week of life, per 1000 registered births (Sidebotham & Walsh 2011). Neonatal mortality refers to babies who were born alive but died within 28 days of birth. Infant mortality is the number of deaths occurring within the first year of life. The infant mortality rate in 2010 was 4.2 deaths per 1000 live births, the lowest ever recorded for England and Wales (ONS, 2012). The report also noted that infant mortality rates were high among babies of mothers aged under 20 years and over 40 years. The infant mortality rate in Scotland in 2010 was 3.7 per 1000 births (Scottish Government 2012).

Morbidity refers to injury or illness resulting from pregnancy or birth (House of Commons 2009). In the UK, the overall number of maternal deaths has fallen over the last 3 years (CMACE 2011). However, this period also saw a rise in the number of women dying from infection, particularly community-acquired infections involving β-haemolytic streptococcus Lancefield group A (CMACE 2011).

Public health and provision for maternity services

The provision for maternity services should include high-quality midwifery services, which have a well-educated workforce, who understand the principles of the public health agenda and how it can impact on the health and well-being of individual women and their families. Midwives in the UK have been an all-graduate profession since 2008, with clearly defined standards for that education set by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC 2009). In the UK, midwifery is regulated by the NMC which sets standards for high-quality care developed to safeguard the health and well-being of the public. This includes a focus on all aspects of public health relating to pregnancy and childbearing women, including sexual and reproductive health services. The engagement of midwives needs to be collaborative in nature, working across the health and social care sectors, as well as being able to provide continuity of care for the family throughout pregnancy, birth and beyond.

Public health focuses on enabling everyone to take responsibility for their own health, preventing disease and supporting the whole population towards understanding the benefits of a healthy lifestyle. The role of the midwife in this key process acknowledges that midwives see women at a critical period in their lives, at a time when they are focusing on their own health and that of the unborn child. This provides a window of opportunity to educate and inform on the benefits of a healthy life style, at a time when the broader public health goals and aspirations can be integrated into existing midwifery practice.

In 2010, an independent report by Sir Michael Marmot reviewed the heath inequalities across England and concluded that inequalities in heath were derived from social inequalities (Marmot 2010). The report suggested that health outcomes could be significantly improved by fairer distribution of health and social life opportunities, particularly for women and children. One of the key focuses on this was giving every child the best start in life.

From a midwifery perspective, this called on midwives to focus more on the public health elements of their role. In 2010, the Midwifery 2020 report, a four-country Chief Nursing Officer-commissioned report looking at the direction of midwifery services and roles across the UK for the next decade, devoted an entire section to the public health role of the midwife. The vision of the Public Health workstream of the report was that midwifery could contribute to a lifetime impact on health: ‘a healthier society right from the start, beginning with excellent midwifery care’ (DH 2010, p3).

The report described two distinct roles for midwives: all midwives have a role in prevention of ill health and promotion of better lifestyles, whilst some midwives may specialise in the detailed area of public health, including having a strategic role both locally and nationally. The report acknowledged that in order to achieve improved population health, the following components were essential:

- midwives as first point of professional contact

- knowledgeable, confident and skilled midwives

- compassionate and emotionally literate midwives

- equality and diversity aware midwives

- respect for midwifery expertise within teams.

Midwives, working collaboratively across the local community, can identify resources and other health and social care professionals who can effectively contribute to a care pathway that is both individualised and holistic, with outcomes focused on a healthier life for mother, baby and family. Midwives, in their unique role, have opportunities to enhance health and well-being through focused parent education and effective antenatal, labour and postnatal care. Many maternity units have midwives who are specialists in smoking cessation, identifying and managing violence against women, reproductive health and family planning. These people will act as a resource for all midwives, as well as being the main contributor to the local public health agenda for both individual women (their families) and the wider population.

The planning of midwifery care and the contribution of midwifery expertise to the development of local health strategies are a key component of enhancing local health outcomes. Continuing professional development means that midwives need to constantly maintain and enhance the skills and knowledge required to engage with local government on public health briefings, as well as understanding local population challenges and needs. Successful commissioning of maternity services is also critical in ensuring that the right service is provided for the right population in a timely and productive manner, whilst being cost-effective. Being aware of local trends, national statistics and strategies around infectious diseases, obesity, smoking, alcohol and drug misuse is essential knowledge for the practising midwife in implementing effective care. An example would be the midwife engaging with organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) which has launched public health briefings for local government, to help local management of major health issues in communities across the UK (NICE 2012).

Specific public health issues of importance to midwifery

The role of the midwife has included public health issues from the earliest days of the profession. Initially these were confined to the reduction of maternal mortality, the management of transmissible disease, such as TB or syphilis, in childbearing women and the promotion of safe infant feeding practices (Berkeley 1922, Clendening 1942, Loudon 1992, Truby King 1945). This remit has expanded to cover many more areas, some of which are mentioned below.

It may seem that in some cases, much of the midwife’s work is attempting to achieve a satisfactory outcome from an unsatisfactory situation, for example, where a woman enters pregnancy in relatively poor health because of diet or lifestyle. However, it is better to prevent or ameliorate the causes of poor health rather than manage the consequences later on (RCN 2012). This is why supporting women to eat healthily and to breastfeed is so important, as this gives the infant a good foundation for better health in later childhood. It is also important that midwives remember that some health practices have different interpretations in other cultures. For example, bed sharing with a newborn infant is part of normal childrearing practice in many cultures around the world, although not necessarily in the UK. Similarly, female genital mutilation (FGM) (female genital cutting/female circumcision) is practised in some cultures but is illegal in the UK.

Some areas of public health are very clearly the responsibility of the midwife. These are usually issues which impinge on the health and well-being of either the mother or the fetus, or both, and which can influence health outcomes. Some of these are briefly discussed here.

Infant feeding

Infant feeding is a key public health concern because the way a baby is fed in the early weeks and months of life influences future health. Breastmilk is a unique biologically active fluid which not only contains all the nutrients the newborn requires but provides some protection against infection, including gastrointestinal infections. There is some evidence that breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of sudden infant death syndrome and diabetes and hypertension in later life (Martin et al. 2005, Owen et al. 2006, Vennemann et al. 2009). There are benefits to maternal health too and women who breastfeed are less likely to develop breast cancer and certain types of ovarian cancer (Jordan et al. 2010, Stuebe et al. 2009). If the mother is unable to breastfeed, or does not wish to, modern infant formula milks are a safe substitute providing that the equipment is clean and sterilised and the formula used according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

It should be remembered that feeding a baby is about more than just putting milk into its stomach. Whichever method is chosen, it should be a pleasurable experience for both mother and child, and one which promotes appropriate infant growth and development and reinforces a loving, nurturing relationship.

Domestic abuse

A definition of domestic abuse or violence is: ‘Any incident of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse (psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional) between adults who are or have been intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality’ (Home Office 2012). The definition also encompasses forced marriage, female genital mutilation and ‘honour’-related violence. The Government has extended the definition to include girls of 16 and 17 years of age. While men can be victims, most are women and 5% of women a year experience one or more assaults (Home Office 2010). The issue is of concern to midwives because the violent behaviour may start, or become worse, in pregnancy. This imperils the health, and sometimes the life, of both the woman and the fetus. Existing children living in a violent home are at risk of abuse. Exposure to violence is also psychologically damaging to a child.

At the first antenatal appointment (the ‘booking’ appointment), midwives should ask (discreetly) if the woman is suffering, or is at risk of, domestic violence. If she is, then the woman is offered support and advice and measures may be taken to protect the child when it is born. Social workers and the police may become involved, depending on the situation. If the woman says that there is no violence, midwives must still be alert to warning signs. These include frequent attendance at the doctor’s surgery with genital or urinary infections, unexplained bruising, especially over the abdomen or breasts, frequent hospital admissions during pregnancy and overbearing or controlling behaviour on the part of the partner. Any discussion with the woman about domestic violence should not take place in the presence of the partner and must be recorded in the hospital (not the hand-held) notes, including care planning and actions taken.