Web Resource 2.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elements that you already know.

Learning outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Explain the ways in which the mentor can initiate the relationship between students and themselves

- Appraise the stages of established models of mentor–student relationships

- Identify factors that influence the mentor–student relationship

- Describe ways of positively developing the relationship with students

Policies for Mentoring

There are several research and policy reasons for the mentoring role. As has previously been stated, practice experience plays an important role in developing students’ learning. Interactions with patients and clients and their families during this experience help students to develop technical, psychomotor, interpersonal and communication skills (Ali and Panther 2008). As well as helping students to put theory into practice, it helps them to develop a professional identity. To enhance the practice experience, it is important to provide students with appropriate support, guidance and supervision within these areas (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC] 2008; see also Health Professions Council [HPC] website – www.hpc-uk.org/standards).

An effective mentor who can help students to clarify any misconceptions, raise questions and work in a safe practice area can provide this support. But, to do this, the mentor and student need to have at least a working relationship. Mentors are expected to provide a supportive learning environment to help students’ progress, assist them in achieving outcomes relevant to the practice placement, and coordinate students’ teaching and assessment needs. They are responsible for understanding the students’ expected learning outcomes and participating with the student in reflective activities. The mentor also participates in formative and summative assessment and the evaluation of the student’s learning to ensure the accomplishment of clinical competencies (NMC 2008). The DH and ENB (2001) state that students need to be active in their own learning but that it is important that they are supported in identifying their learning needs and making the best use of learning opportunities available. Placements must provide adequate support and supervision for students.

The NMC (2008) and the HPC (see website above) set out standards for the mentor and students in practice (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1 Standards for mentors and students in practice

| NMC (2008) | HPC (www.hpc-uk.org/standards) |

| Mentors’ responsibilities | Standards for students in practice |

When nurse education moved into the higher education sector during the 1980s and 1990s with Project 2000, research findings highlighted that at the point-of-registration students were not as clinically skilled as those students who had under-taken pre-Project 2000 programmes (United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Heath Visiting or UKCC 1999). This reinforced the need for competent, clinically based mentors able to support students to learn clinical skills and become fit for practice.

The Dearing Report (National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education 1997) also advocated that students should be fit for practice, fit for purpose and fit for award. The standards and codes of the healthcare and social care professions stipulate that practitioners have a duty to facilitate students to develop their competence. These requirements are also stated in healthcare practitioners’ job descriptions, which are guided by the NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (NHS KSF – DH 2004). Although individual students have different learning styles and identified learning needs, it is necessary to appreciate the requirements of a particular healthcare role. The NHS KSF has been designed as a generic development tool for use throughout the NHS to describe knowledge and skills that are applied within healthcare – knowledge and skills required to perform a particular role (profession) and to support the development of staff in these roles (see Chapter 9 under ‘Using your mentoring skills to further your career’ for more information).

A final reason for having mentoring schemes is the fact that health- and social care professions are practice based so work-based learning is an essential part of the development of a student to become a practitioner fit for practice and fit for purpose.

Initiating the Mentor–Student Relationship

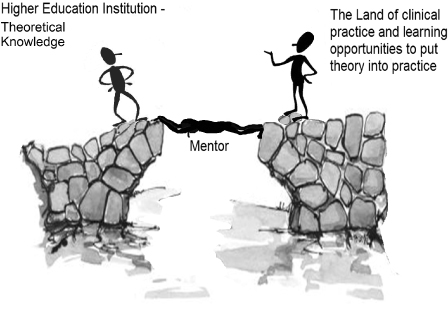

As mentioned above, the health- and social care professions are practice-based so practice education is an essential part of the undergraduate curriculum. The quality of the education depends largely on the quality of the practice experience (Twentyman et al 2006). As discussed in Chapter 1, students need effective practice placements to allow the application of theory to practice. These experiences are essential to the student’s preparation for developing as a competent and independent practitioner (Twentyman et al 2006). But practice education occurs in an environment that can be unstructured, unpredictable and overwhelming (Papp et al 2003, cited in Twentyman et al 2006). Practice placements provide the opportunities for students to observe role models, practise and develop skills, and reflect on what they see, hear and do (Twentyman et al 2006). As they practise in the clinical area, it is essential that students integrate theoretical concepts learned in the higher education institutions (universities) with practice in the clinical area. Mentors are the bridge between these two elements, and so the relationship between the mentor and the student is of critical importance because this is a major influence on the quality of a practice placement for a student (Figure 2.1). When students first arrive in a practice area, they may initially feel that they are under pressure to demonstrate their newly acquired theoretical knowledge from university. They may feel that they need to fit in and be seen to function in ways that they perceive the practitioners with whom they are now working require.

Cahill (1996) undertook a qualitative analysis of student nurses’ experiences of mentorship and found that the relationship between the mentor and the student is the single most important factor in creating a positive learning environment. Students also identified that the skills and attitudes of staff, mentors’ attitudes towards them and access to relevant learning opportunities were paramount in achieving positive learning outcomes.

Twentyman et al (2006) state that staff who adopt a positive attitude, and so influence the work culture, have been identified as supporting students’ learning.

They claim that poor treatment of students in the workplace is common.

Activity 2.1

Can you think of reasons why at times students are not treated well during their practice placement? What affect do you think this can have on the student?

Several reasons are stated in the literature including the following:

- Staff shortages

- Increased workload

- Mentors’ lack of teaching skills

- Mentors and other staff feeling threatened by students.

If students do not feel supported in the clinical environment because they are treated with hostility or ignored, they are unable to participate in the necessary activities to further their learning and achieve their competencies. The amount of interest that the mentor demonstrates in the learning needs of the student, and the key role that the mentor plays in their achievement, are vital to the student’s development. Mentors are crucial in the development of a supportive learning environment through their own attitudes to study and to each other. Students’ learning experiences during clinical placements are heavily influenced by the clinical area’s culture of which the mentor is part (Twentyman et al 2006). How the clinical area functions as an educational environment may depend, for example, on whether the student is considered solely as someone to be assessed, as a student there to learn or as a colleague (Edwards et al 2001) (see Chapter 6).

Students considered a good clinical environment to be an area that viewed students as less experienced colleagues and treated them as such. Practice areas that welcomed, appreciated and incorporated students into the team were considered positive learning experiences (Twentyman et al 2006). Every clinical area is unique – it will take time for the student to get to know the culture of the area. They have to get to know the people and how they interact with each other, the routines, the hierarchy structures and the administrative demands (Phillips et al 2000). Over the years particular ways of doing things in practice are established, none of which is usually written down. Students arriving at a practice area have to get their bearings in situations that, to the practitioners, seem obvious. In some areas everyone seems so busy that a student may be reluctant to interrupt them. The student usually has to learn about these aspects quickly so this is where the student’s relationship with the mentor is important.

It is therefore essential that an effective relationship is established where the mentor offers support to the student but the mentor can also be objective and analytical. Friendship can develop between the mentor and student and, although this enhances the student’s experience of the placement, it can raise concerns that the student’s achievements may not be a true reflection of his or her competency because the mentor’s assessment may be subjective (Wilkes 2006). A negative practice experience can also cause problems for the mentor and the student; such an experience can have detrimental effects on the mentor so that they may be reluctant to support students in the future. The student’s learning can also be adversely affected.

Web Resource 2.2: Potential Pitfalls in Mentoring and Why They Occur

Web Resource 2.2: Potential Pitfalls in Mentoring and Why They Occur

To prevent potential problems such as these, please visit the accompanying web page and read potential pitfalls in mentoring and why they can occur.

Stages of the Mentor–Student Relationship

Mentors and students start as strangers to each other and so the goal is to establish a practical and helpful working relationship (Price 2005).

If the relationship is based on mutual respect and a sense of partnership then the student’s learning will be enhanced. The mentor–student relationship develops over time and passes through stages.

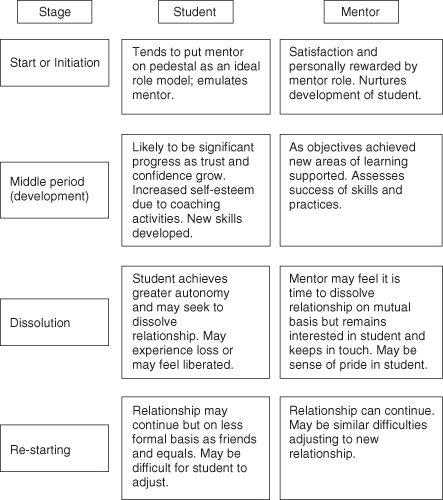

Kram (1983) stated that the relationship developed and changed through four identifiable stages: start or initiation, middle period or development, dissolution and re-starting (Figure 2.2).

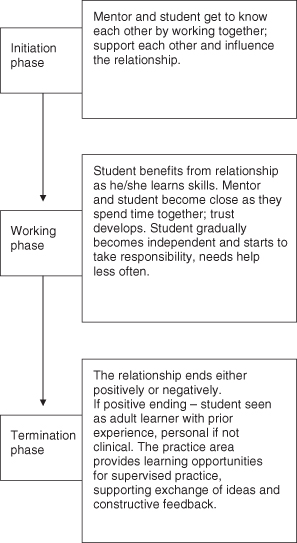

Morton-Cooper and Palmer (2000) identify three stages: the initiation phase, the working phase and the termination phase. These stages are very similar to Kram’s first three stages (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Three stages of the student–mentor relationship.

(Based on Morton-Cooper and Palmer 2000.)

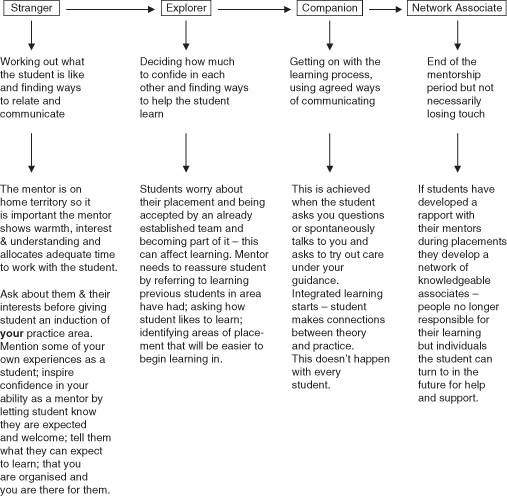

Price (2005) argues that this relationship doesn’t have to be one of close friendship although the mentor, who is on home territory, needs to make the student feel welcome by demonstrating warmth, interest and respect for the student and his or her learning. Price states that the more a mentor can appreciate and respect, and in some cases empathise with, the emotions associated with anxiety, uncertainty, lack of confidence and inquisitiveness, the more effectively the mentor will be able to help the student. The mentor–student relationship starts with a rapport. The relationship can be functional rather than friendly, especially if the mentor has to assess the student’s performance at a later date. Price sets out four stages to describe the developing relationship with the student (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Four stages to developing a relationship with the student

(Price 2005, reproduced with permission).

Again Price’s approach is very similar to the previous two. But the important points to consider are that the mentor and student are usually two individuals who initially do not know each other. Adopting the mentor and student roles would suggest that they have to communicate with each other, develop a rapport and develop some kind of working relationship. Generally a student is allocated to a practice area for a stipulated period of time, during which the student needs to achieve competencies so a working relationship has to be established quickly.

Establishing a Mentor–Student Relationship

If, as a mentor, you can establish a good relationship and mutual trust between yourself and a student, you will find that students are more likely to be receptive to new ways of thinking and behaviour. It is therefore important that the mentor creates a comfortable atmosphere. Several aspects that contribute to a comfortable atmosphere are quite subtle, such as:

- attitudes

- creating a feeling of safety

- providing conditions conducive to learning.

Web Resource 2.3: Establishing an Effective Mentor–Student Relationship

Web Resource 2.3: Establishing an Effective Mentor–Student Relationship

Go to the website to learn more about establishing an effective mentor–student relationship.

Activity 2.2

Considering these aspects, what can you do as a mentor to help establish a working relationship with your student?

According to Bayley et al (2004) mutual trust is the basis of an effective mentor–student relationship. For a student to trust a mentor competency and caring are required.

If a mentor demonstrates only one of these attributes – being only competent or caring – trust will not be established. If a student thinks that a mentor is competent but not caring towards the student, the student may have respect for the mentor but will not necessarily trust him or her. The mentor can care about the student and the things that are important to the student, but, if the latter does not feel that the former is competent or capable of performing skills, there will be no trust. In this case the student will have affection for the mentor but will not trust him or her (Bayley et al 2004).

If a student does not trust a mentor he or she will not feel comfortable or competent to move out of the comfort zone of usual interactions with people or of undertaking tasks. Individuals generally do not need to learn new things while in their comfort zone and so are unlikely to change any behaviours (Bayley et al 2004). If, as a mentor, you push a student too far, he or she may panic and freeze, and will be unlikely to learn from the experience, except how to avoid it happening again. The best approach, according to Bayley et al (2004), is to help students out of their comfort zone, but not into a panic zone by encouraging them into the discomfort zone instead. Students are more likely to change and learn how to do things differently while in this zone. But to encourage students to leave their comfort zone, you as the mentor need to help them feel safe. To achieve this, the student needs to trust you.

Bayley et al (2004) suggest ways of encouraging students to trust their mentor:

- Mentors doing what they say they are going to do and not making promises that they can’t keep or will not keep

- Listening to students and telling them what the mentor thinks they are saying – students trust mentors when they feel that the mentor understands them

- Understanding what matters to students – students trust mentors who appear to be looking after the student’s interests

Mentors can encourage effective relationships with students if they:

- set and agree ground rules at the outset; it is important that the roles and relationships are known and understood from the start

- ensure that the student understands his or her own responsibilities

- are able to talk to each other and are willing to listen to each other; it is especially important to allow the student to voice their views and concerns so the mentor should not speak too much

- respect each other

- know their limitations and don’t try to hide them – although it may improve their image, it does not build trust

- don’t confuse trustworthiness with friendship – trust does not automatically come with friendship

- are honest and tell the truth

- stick to their mentoring role, and don’t stray into management

- remember that good relationships are built up by regular contact not by crisis management. Even though mentors within health and social care work with their student on a regular basis, some students do not like to ask questions or be seen to be bothering their mentor until there is a problem. As a mentor you need to be aware of the student who, although working with you, does not question you or ask for help in achieving competencies.

(Based on Bayley et al 2004; Kay and Hinds 2007.)

Establishing a rapport with a student depends on a mix of assessing and responding to each other’s feelings, thoughts and intentions. Carl Rogers (1983) transformed the traditional teacher’s role to one of facilitator of learning. Rogers believed that all individuals have an innate tendency to move in the direction of growth, maturity and positive change, i.e. students have the motivation and ability to change behaviour and they are the best qualified to decide the direction of that change; they do not need to be told what to do. The mentor is the professional sounding board who facilitates the learning experience (Best et al 2005). Rogers identified six qualities that can lead to easy and safe communication and can help the mentor focus on the student and establish a rapport:

1. Genuineness or realness that involves being his- or herself in a relationship by sharing attitudes and feelings and some self-disclosure.

2. Acceptance and respect in a relationship involve communicating that the student is a worthwhile, unique and capable individual. It is also about accepting that the student has a point of view which, whether or not the mentor agrees with it, is valid to the student and so worth listening to.

3. Empathy that is a shared understanding and sensitivity between the mentor and the student. It involves feeling and understanding how the student feels in particular situations.

4. Warmth involves communicating commitment to the mentorship relationship and its importance. Communicating warmth is not as easy as it sounds. Some people do find it difficult to both give warmth and receive it.

5. Openness means being accepting of the student’s expression of thoughts and feelings. It can mean being open to students’ different cultural needs as well as being open to the potential for change.

6. Confidentiality is a key attribute in trusting relationships but sometimes there can be a conflict of interest in practice. The concern is the level of confidentiality that is felt to be important to the student and that which the mentor can actually agree to. An example of this might be students who are not progressing satisfactorily in practice and the university needing to be informed. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN 2005) state that, as a registered practitioner, a mentor’s primary role is to protect the public but this can cause a dilemma for the mentor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree