Chapter 14 The impact of globalisation on health

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

identify the significant impacts of globalisation on population health, particularly the incidence of communicable and non-communicable diseases

identify the significant impacts of globalisation on population health, particularly the incidence of communicable and non-communicable diseases understand the distribution of the global burden of disease in high-, middle- and low-income countries

understand the distribution of the global burden of disease in high-, middle- and low-income countriesIntroduction to globalisation

Globalisation is a relatively new term used to describe a very old process, and has only been in use for around 25 years. According to Stanley Fischer, the former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund, the word ‘globalisation’ was never mentioned in the pages of The New York Times during the 1970s, and appeared less than once a week in the 1980s (Fischer 2003). Using the Google search engine, the key word ‘globalisation’ yielded 18.8 million links in March 2011, compared with 1.6 million links in 2002. The term is becoming more widely used every day.

Globalisation is a historical process that began with our ancestors moving out of Africa to spread all over the globe (Chanda 2002). It is likely that the first group of ‘migrants’ (there were no national borders then) left their homes and villages in central Africa and moved to the Mediterranean about 100 000 years ago, and the second migration was to Asia about 50 000 years ago (Chanda 2002). In the historical era (in general, the period for which we have written records), most of those people moving from country to country were traders, preachers, adventurers and soldiers.

Reflection

Globalisation is defined in Box 14.1. In the process of globalisation, what would bring societies and citizens closer together? According to the International Labour Office, ‘trade, investment, technology, cross-border production systems, flows of information’ and ease of communications are all factors that facilitate the process of globalisation (Kawachi & Wamala 2007b p 5). National and international policies are necessary to support globalisation. These policies include ‘trade and capital market liberalization, and international standards for labour, the environment, corporate behaviour, and agreements on intellectual property rights’ (Kawachi & Wamala 2007b p 5).

Global communication

The recent increase in globalisation is associated with technological developments, mainly in transportation and communication that have significantly reduced the ‘size’ of the world. The speed of communication is now faster than we could ever have imagined. For example, in the late nineteenth century, it took the Queen of England, Queen Victoria, 16.5 hours to send a greeting message to the American President James Buchanan across a transatlantic cable (Chanda 2002). Today we can communicate with each other through telephone, fax, email and videoconferencing almost instantaneously.

The increased speed of communication, accompanied by a decrease in cost, has made communication such an effective way of connecting the world. In 1930, a three-minute telephone call from New York to London cost US$300, now it can cost less than 10 cents (Chanda 2002). The decreasing cost of telecommunications and the advent of mobile phone technology have greatly increased accessibility for the majority of people in most countries and facilitated communications. Mobile phones were introduced into Australia in February 1987. Australia, with a population of just over 21 million people in June 2007 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007) and 6.5 million households, had more than 3.2 million mobile phone users in 2007 (Allen 2007).

Internet usage is another sign of globalisation in communication. A report by a marketing group in November 2007 indicated that 19.1% of the world’s population (6.6 billion) use the internet (Miniwatts Marketing Group 2007). Among the 1.3 billion Internet users in the world, about 37% are from Asia, 27% from Europe, 19% from North America, 10% from Latin America, 3.5% from Africa, 2.7% from the Middle East and 1.5% from Australia/Oceania (Miniwatts Marketing Group 2007). Globally, Internet usage increased by an average of 250% over the period 2000 to 2007. In the Middle East the increase was 920%, in Africa 880%, in Asia 304% and in Europe 227%. China, with the world’s largest population, had 22.5 million Internet users in 2000 (about 1.7% of the country’s population); by 2007 the number had increased to 162 million (12.3% of the population) (Miniwatts Marketing Group 2007). Australia had 6.6 million Internet users in 2000, and 14.7 million in 2007 (respectively, about 34% and 70% of the population) (Miniwatts Marketing Group 2007). No other communication technology has seen such an increase in uptake in such a short time frame.

National and international air travel

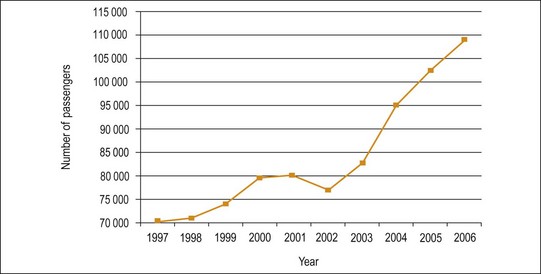

The affordability of air travel has also increased dramatically. In Canada, for example, there were 54 million air passengers in 2002, and 64 million in 2005 (Cherniavsky & Dachis 2007). In Australia in 1997, there were about 70 000 passengers (domestic and international) flying through Australian airports (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth). By 2006 this figure had increased to 110 000 passengers (Fig. 14.1). Air travel contributes to local economic development itself, but in combination with related services such as hotels, local transport and food, it is an important contributor to the overall economy. The most significant impact of this increased air travel is that it has made the world a face-to-face meeting place, thus greatly enhancing global interconnectedness and interdependence. It has also meant that illness and disease spreads rapidly across the globe as people move from country to country in a relatively short amount of time.

Fig. 14.1 Number of air traffic passengers travelling through Australia from 1997 to 2006.

(Source: Australian-Transport 2007 Aviation Statistics 2008)

Research has shown that poverty rates have dropped significantly in countries such as China where globalisation has taken a strong foothold, compared with regions less affected by globalisation, such as sub-Saharan Africa, where poverty rates continue to be high (Sachs 2005). This argument was supported by the International Monetary Fund Policy Discussion Paper of 2001, which reported that ‘countries that have embraced openness to the rest of the world’ have done better in their economic development than those that have not (Masson 2001 p 1).

Critics of globalisation believe that the rapid flow of capital and consumer goods has caused damage to the planet and increased poverty, socio-economic inequality, injustice and the erosion of traditional cultures. Many organisations in developed countries involved in globalisation have failed to consider the welfare of underprivileged countries and people of low socio-economic status, or the interests of the natural world (Bakan 2004). To reduce the negative impact of globalisation on poorer countries, the Secretary General of the United Nations, Mr Ban Ki-moon, told the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on 4 March 2008 in New York that ‘2008 must be devoted to helping the bottom billion of the world’s poorest to tap into global economic growth … In a globalizing world, we require an international economic environment that fosters development; … today’s UN cannot simply champion development, it must deliver every day on its promises’ (UN 2008a).

How many people around the world do you think might be supporters of globalisation? How many people around the world do you think might be opponents? A survey on people’s perceptions of globalisation was conducted in 2006 in a range of countries representing 56% of the world’s population territories (University of Maryland 2007). The respondents were asked a series of questions concerning their ideas about globalisation. Table 14.1 presents the results of that study.

TABLE 14.1 The view of globalisation by country

| Country | Mostly good (%) | Mostly bad (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 65 | 27 |

| China | 87 | 6 |

| France | 51 | 42 |

| Iran | 63 | 31 |

| India | 54 | 30 |

| Israel | 83 | 10 |

| Mexico | 41 | 22 |

| Philippines | 49 | 32 |

| Russia | 41 | 24 |

| South Korea | 86 | 12 |

| United States | 60 | 35 |

(Source: University of Maryland 2007 www.WorldPublicOpinion.org)

The survey showed that support for globalisation is remarkably strong throughout the world. The survey question, ‘Globalisation, especially increasing connections of our economy with others around the world, is mostly good or mostly bad’ was asked in 17 countries and the Palestinian territories. In every country, positive responses outweighed negative ones. It is possible that the level of support is related to the extent of the countries’ export economies. For example, respondents in China, South Korea and Israel expressed strong support for globalisation. The greatest scepticism about globalisation was found in Mexico, Russia and the Philippines, with less than 50% of the population regarding globalisation as ‘mostly good’ (University of Maryland 2007).

In Australia, the same survey was conducted by the Lowy Institute in July 2006 (University of Maryland 2007); it showed that most Australians viewed globalisation favourably. About 65% of Australians considered globalisation to be ‘mostly good’ for the country, while only a quarter (27%) said that it is ‘mostly bad’. Almost all Australians interviewed (98% of respondents) believed that protecting Australian jobs should be a foreign policy goal, and 83% considered that it is ‘very important’. There are links between having a job and socio-economic status, that is, people who are employed generally enjoy a higher status; moreover, socio-economic status and health are clearly linked (see Chapter 6 for more information regarding the social determinants of health).

Activity

Globalisation in population health

Globalisation affects population health by changing the ways in which people interact across boundaries, including ‘spatial (territorial), temporal (time) and cognitive (thought processes)’ boundaries (Lee 1999 p 249). For example, global trade has led to increased spatial and temporal exposure to infectious disease through the rapid cross-border transmission of communicable diseases (notable examples include SARS and avian influenza). Similarly, global trade also increases the risk of chronic diseases, through the marketing of unhealthy products and risk behaviours, such as tobacco smoking and the consumption of fast food (Smith 2006). In addition, the global distribution of health-related goods (e.g. pharmaceutical products, medical equipment) and people (both patients and health professionals) is another example of how the health of the population might be impacted. An example is ‘medical tourists’. This is a relatively new term, referring to patients from other countries who travel for clinical treatment, mainly in surgery. Medical tourism is now a rapidly growing industry.

For hospitals seeking medical tourists, accreditation by the Joint Commission International (JCI) is a crucial stamp of approval. The number of JCI-accredited foreign medical sites increased from 76 in 2005 to more than 220 in 2008 worldwide (Shetty 2010). For example, the Confederation of Indian Industry predicts that India will see revenues of US$2 billion from medical tourism by 2012. To facilitate the further development of this industry, the Indian Government has created a special medical visa that lasts up to 1 year to make it easier for patients to enter the country (Shetty 2010).

Patients become medical tourists for two main reasons – finance and technology. In the USA the lack of health insurance makes many treatments unaffordable. A single heart valve replacement in 2006 cost U$9 500 in India, but U$273 395 in the USA. In the UK, for example, long waiting lists and the high cost of private care are pushing patients to become medical tourists. Patients from the Middle East and Africa travel long distances for surgery because the medical technology or expertise is lacking in their countries (Shetty 2010).

In this section of the chapter, we will discuss two of the main aspects of the effects of globalisation on population health. First, we will consider the impact of globalisation with regard to the increased exposure to infectious diseases, and second, the increased risk of chronic diseases. The background to infectious diseases and the individual strategies directed towards control and management are outlined in Chapter 10.

Globalisation of infectious diseases

Arguably, infectious diseases cause the greatest threat to population health because of the potential for such diseases to rapidly spread to large numbers of people across the world. People’s travel can facilitate the movement of infectious pathogens. The potential for geographical spread is particularly apparent if you consider that most infectious diseases have an incubation period exceeding 36 hours, and that any part of the world can now be reached within 36 hours (Kawachi & Wamala 2007a). For example, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) demonstrates the rapid movement of infectious pathogens from country to country.

SARS is a viral respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus. In general, SARS patients have a raised body temperature (greater than 38°C), headache, diarrhoea, mild respiratory symptoms and pneumonia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2008). The main way that SARS spreads is by close person-to-person contact. The virus is transmitted most readily by respiratory droplets (via sneezing and coughing), which can spread up to 1 metre in the air (CDC 2008).

SARS was first reported in China in February 2003. Within 11 weeks it had spread to 27 countries in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia (Cherry 2004). The rapid spread of SARS and the high case fatality rate prompted significant reactions around the world. Some have compared the SARS outbreak to that of the ‘Spanish flu’ of 1918–1919, which killed over 20 million people (Yale 2003). Spanish flu was spread by people travelling on trains and by troops on ships, while SARS was spread by people travelling by air, which facilitated the movement of SARS from Asia to North America and Europe in a matter of days (Yale 2003). While SARS has caused comparatively fewer deaths than the Spanish flu, it spread far more rapidly due to the intensification of global travel over the past several decades. The rapid spread of SARS caused fear and considerable disturbance to people’s lives across the world. As we saw earlier in Figure 14.1, the reported number of domestic and international passengers flying through Australia showed a significant decrease in 2002, which is attributable, at least in part, to the SARS outbreak.

Merson (2003) claimed that ‘SARS proved health is a global public good: And the need to boost domestic public health and international cooperation’ (the full article can be found on the YaleGlobal website). As the economic consequences of SARS became apparent (already about US$150 billion worldwide by September 2003), countries scrambled for effective solutions. However, individual nation-states were ill equipped to manage an illness like SARS by themselves for a number of reasons, including limited medical expertise and a lack of understanding about the disease (Kickbusch 2003). This example demonstrates the need for a worldwide collaborative approach.

It was through a global public health approach and inter-country cooperation in developing and implementing ‘effective control strategies, including early isolation of suspected cases, strict infection control measures’ in health settings and ‘meticulous contact tracing and quarantine’ (Zhong & Wong 2004 p 270), that the global SARS outbreak was contained by July 2003.

Research has shown that global resources to counter emerging infectious diseases (EID) are ‘poorly allocated, with the majority of the scientific and surveillance effort focused on countries from where the next important EID is least likely to originate’ (Jones et al. 2008 p 990). The ‘greater surveillance and infectious disease research effort’ are allocated ‘in richer, developed countries of Europe, North America, Australia and some parts of Asia, than in developing regions’ (Jones et al. 2008 p 992); while the ‘predicted emerging disease hotspots due to zoonotic pathogens from wildlife and vector-borne pathogens are more concentrated in lower-latitude developing countries’ (Jones et al. 2008 p 992). Therefore, in the era of globalisation, the international investment needs to be targeted at lower-latitude developing countries for capacity building to detect, identify and monitor infectious diseases. As shown in SARS, emerging infectious diseases are every country’s problem.

Activity

Reflection

Did you think about the links between this activity and the content of Chapters 5 and 6, to clarify some of the potential factors that could either promote or impede the spread of SARS? Did you consider the contribution of research to understanding the nature of the disease, policies related to travel, social gathering or social distancing, and the possible cultural differences in managing the media and public panic?

Globalisation and chronic diseases

The main global chronic diseases today include heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes (WHO 2008). These are generally the consequences of intermediate risk factors, such as raised blood pressure, raised glucose levels, abnormal blood lipids (particularly low-density lipoprotein and cholesterol) and overweight (Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 25) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30). The most important modifiable risk factors are unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and tobacco use. These risk factors, in conjunction with the non-modifiable risk factors of age and heredity, explain the majority of new cases of heart disease, stroke, chronic respiratory diseases and some cancers (WHO 2006). To explore the effects of globalisation on the modifiable risk factors, the next section discusses tobacco use and unhealthy diets.

Tobacco use

Contemporary statistics suggest that 75% of the world’s cigarette market is controlled by just four companies. They are China National Tobacco Corporation, Japan Tobacco, British American Tobacco and Philip Morris. While cigarette consumption in most high-income countries has declined, it has increased threefold, from 1.1 billion to 3.3 billion cigarettes in total per year in low- and middle-income countries between 1997 and 2000 (Kawachi & Wamala 2007b).

Tobacco-related diseases were responsible for nearly 4.8 million premature deaths in 2000 (Ezzati & Lopez 2003), and about 5.4 million in 2005, 6.4 million in 2015 and 8.3 million in 2030 (Mathers & Loncar 2006b). By 2015, tobacco is projected to be responsible for 10% of all deaths globally (Table 14.2) (Mathers & Loncar 2006b). Globalisation has led to this increase in cigarette consumption in the middle- and low-income countries. Let us consider tobacco consumption in China as an example.

TABLE 14.2 Projected global tobacco-caused deaths by 2015 – adapted from baseline scenario

| Cause | Number of tobacco-caused deaths (million) | |

|---|---|---|

| All causes | 6.43 | |

| Tuberculosis | 0.09 | |

| Lower respiratory infections | 0.15 | |

| Malignant neoplasms | 2.12 | |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung cancers | 1.18 | |

| Mouth and oropharynx cancers | 0.18 | |

| Oesophagus cancer | 0.17 | |

| Stomach cancer | 0.12 | |

| Liver cancer | 0.10 | |

| Other malignant neoplasms | 0.34 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.13 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.86 | |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 0.93 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.52 | |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 0.24 | |

| Respiratory disease | 1.87 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 1.76 | |

| Digestive disease | 0.20 | |

(Source: Mathers & Loncar 2006a)

In China, chronic diseases account for an estimated 80% of deaths and 70% of disability – adjusted life years (DALYs) lost (Wang et al. 2005). Cardiovascular diseases and cancer are the leading causes of both death and the burden of disease. The exposure to risk factors is high. For example, more than 300 million men smoke cigarettes, and if current smoking patterns persist, two million out of the seven million deaths related to smoking worldwide will occur in China (Wang et al. 2005). This estimation does not include passive smokers.

The China Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study (Yin et al. 2007) investigated a sample size of over 20 000 and demonstrated that exposure to passive smoking is associated with an increased prevalence of COPD and respiratory symptoms. It was estimated that 1.9 million excess deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among those who had never smoked could be attributed to passive smoking in the current population in China (Yin et al. 2007).

In addition to the direct health effects of smoking, indirect consequences include the financial cost, especially for a developing country such as China. It was found that in some Chinese rural areas expenditure on tobacco occurs at the expense of education, medical care, insurance and investment in farming (Wang et al. 2006). The excessive medical spending attributable to smoking and consumption spending on cigarettes combined are estimated to be responsible for impoverishing 30.5 million urban residents and 23.7 million rural residents in China (Liu et al. 2006). In China, smoking-related expenses push a significant proportion of low-income families into poverty, making vulnerable people more susceptible to health problems.

China’s membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO) has presented unprecedented opportunities for the multinational tobacco companies to penetrate the world’s largest cigarette market (Kawachi & Wamala 2007a). Since the late 1990s, these companies have signed numerous cooperation agreements with China to modernise manufacturing facilities, improve crop yields and build crop-processing plants (Kawachi & Wamala 2007a). China now grows cash crops of tobacco and produces the largest amount of tobacco in the world, whereas previously it was an agrarian, subsistence economy. It is critical that the Chinese central government, including the ministries of health, finance and foreign affairs, work together to tackle this serious tobacco problem.

Activity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree