Chapter 1 The global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS

Overview of the Global Epidemic

There have been tremendous changes in the global HIV epidemic since the 1990s with declines in incident infections, increased coverage of antiretroviral therapy, stabilization or declines in HIV prevalence, reduction of mother-to-child transmission, and reduction in AIDS-related deaths. Many of these advances resulted from the dramatic increase in HIV program investments in low- and middle-income countries, which grew from US$1.4 billion in 2001 to US$15.9 billion in 2009. These resources have supported HIV treatment for over 6 million people worldwide [1].

Nonetheless, even with the recent stabilization of the global epidemic, HIV/AIDS has had devastating impact on lives worldwide and especially in sub-Saharan Africa. There were an estimated 33.3 million (31.4–35.3 million) people globally living with HIV at the end of 2009, a number that may continue to increase as incident cases continue to accrue and deaths to fall secondary to antiretroviral therapy. A decrease in new HIV infections has occurred, from an estimated 3.1 million (2.9–3.4 million) in 2001 to 2.6 million (2.3–2.8 million) in 2009 [1].

There is genetic, epidemiologic, and behavioral heterogeneity in the global HIV epidemic, with different regions disproportionately impacted by the virus. Generalized spread has occurred in sub-Saharan Africa while HIV/AIDS elsewhere has largely been restricted to key vulnerable populations (men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, and sex workers and their clients) [1].

Phylogenetically, two types of HIV are recognized, HIV-1 and HIV-2; within HIV-1 there are four groups, group M, group N, group O, and group P and within HIV-2, eight groups. HIV-1 group M is the predominant cause of the global epidemic and shows great genetic diversity with nine subtypes (A–D, F–H, J, and K) and at least 48 circulating recombinant forms. HIV-1 groups N, O, and P are rare and essentially restricted to persons from Central Africa. The single most common subtype of HIV-1 is subtype C, which affects nearly 17 million people in southern Africa, parts of East Africa, and Asia [2]. The number of HIV-2 infections globally is small and seems to be decreasing; most are associated with West Africa.

Measurement of Disease

Methods for measuring HIV incidence and prevalence continue to evolve to more accurately measure disease burden [3]. The progression of the disease, late manifestation of symptoms, HIV testing behaviors, and antiretroviral therapy all challenge our ability to use epidemiologic and laboratory methods to measure HIV incidence and prevalence [4, 5].

Surveillance methods have drastically improved within the past decade. In low- and middle-income countries, sentinel surveillance among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics has been the cornerstone of efforts to estimate HIV prevalence in the general population. Pregnant women are by definition sexually active, give insight into prevalence trends in the general population, and are easy to survey since they access health services [6]. The coverage and quality of this surveillance approach has improved to provide more representative data [7].

Countries with generalized HIV epidemics, meaning that HIV transmission is sustained in the general population outside of core groups, have in addition been conducting periodic national household surveys to estimate national HIV prevalence and collect behavioral information related to HIV acquisition and transmission. Arbitrarily, an HIV prevalence greater than 1% has sometimes been assumed to indicate generalized spread, although this assumption is unreliable. Several high-burden countries have now conducted more than one household survey, usually at approximately 5-year intervals, to monitor trends and measure impact of HIV programs. These national surveys are used to adjust prevalence levels from sentinel site surveillance in pregnant women to more accurately reflect those of the general population. Common experience has been that in relation to nationally representative household surveys, sentinel site surveillance based on pregnant women attending antenatal clinics has tended to overestimate HIV prevalence. This realization was key to UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) lowering global HIV estimates considerably in late 2007 [3].

Countries with low-level or concentrated epidemics conduct biological and behavioral surveys among high-risk populations, which include injection drug users, men who have sex with men, and male and female sex workers. New methods for accessing higher-risk populations that are often hard to reach continue to be validated [8]. Recently, countries with generalized epidemics have also been conducting biological and behavioral surveys among higher-risk populations that are disproportionately affected even in generalized epidemics. An important epidemiologic exercise has been estimating the respective population sizes of these high-risk groups, allowing estimates of their total numbers of HIV infections and contributions to overall HIV infection incidence, which is useful for allocation of resources for prevention of different modes of transmission.

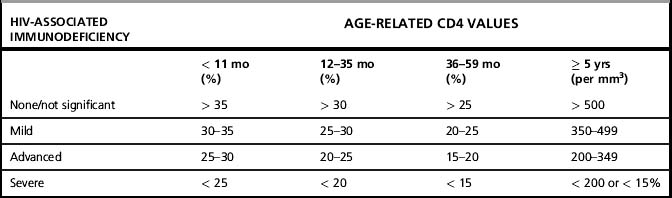

The revised 2006 case definitions and staging system proposed by WHO provide standardized definitions for global use to improve patient management, patient monitoring, and surveillance [9, 10]. Four clinical stages and four immunological stages were established (Table 1.1a and 1.1b), reflecting the known decline in clinical status and CD4 cells with the progression of HIV disease. The surveillance definitions for HIV/AIDS were also revised to include three categories: HIV infection, advanced HIV disease, and AIDS (Table 1.2). Although a standard case definition for primary (acute) HIV infection is not established, identifying and reporting cases of primary infection may be important because these represent very recent infections. Symptomatic primary HIV infection presents one to four weeks after HIV acquisition and may include any of the following symptoms:

Table 1.1a WHO clinical staging of established HIV infection

| HIV-associated symptoms | WHO clinical stage |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 1 |

| Mild symptoms | 2 |

| Advanced symptoms | 3 |

| Severe symptoms | 4 |

Table 1.2 WHO case definition for HIV infection for reporting for adults and children [1]

Note: AIDS case reporting is no longer required if HIV infection or advanced HIV infection is reported.

1 Where access to virological testing in children less than 18 months is limited, confirmation of HIV infection can be obtained from repeat testing on the same specimen where laboratory quality assurance, including specimen handling is guaranteed.

2 AIDS in adults and children is defined as clinical diagnosis (presumptive or definitive ) of any one stage 4 condition (as defined in annex 1); OR immunological criteria in adults and children ≥ 5 years with documented HIV infection first-ever documented CD4 count less than 200/mm3 or %CD4 <15; or in a child < 5 years with documented HIV infection first-ever documented CD4 of %CD4 < 25 in those infants ≤ 11 months of age; %CD4 < 20 in those aged 12–35 months, or %CD4 < 15 in those aged 35–59 months.

Countries with established national HIV case surveillance systems (mostly Western countries) use back-calculation methods or direct calculation to determine HIV prevalence and incidence [4, 11]. Other countries rely on epidemic models based on data from surveillance of key populations to estimate HIV prevalence and incidence and monitor trends [12].

HIV Transmission

Sexual transmission

Most HIV infections are transmitted sexually, with heterosexual transmission being the dominant mode of transmission globally. As with all modes of transmission, infectiousness is determined by viral load: the higher the viral load, the more likely that transmission will occur. Other sexually transmitted infections, especially ulcerative conditions including HSV-2 infection, increase viral shedding in genital fluids and transmissibility [13]. Male circumcision is partially protective (approximately 50–60% efficacy) against heterosexual acquisition of HIV [14]. Although there is no definitive evidence that male circumcision protects against male-to-female transmission, indirect benefit to women will ultimately result from reduced HIV prevalence in men. The risk of HIV infection increases with the number of sex partners, and because of their high viral load, persons recently infected may contribute disproportionately to spread [15]. The highest rates of HIV infection are found in persons with the greatest rate of partner change such as sex workers. There is debate about the epidemiologic impact of concurrent versus sequential partnerships, the former suggested as establishing more efficient transmission networks. In the generalized epidemics of southern and eastern Africa, a substantial proportion of heterosexually transmitted infections occur in stable or long-term sero-discordant couples.

High rates of HIV infection are found among men who have sex with men almost everywhere they have been studied. Recognition that male-to-male sex occurs in virtually all countries, including in sub-Saharan Africa, is relatively recent, as is the documentation of high rates of HIV infection in men who have sex with men in societies suffering generalized HIV epidemics [16].

Mother-to-child transmission

HIV can be transmitted from mother to child in utero, around delivery, or after birth during breastfeeding. Prophylaxis or treatment with antiretroviral drugs has drastically reduced the vertical transmission rate, which without intervention ranges from about 15% in non-breastfeeding women to 45% for those breastfeeding up to 24 months [17].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree