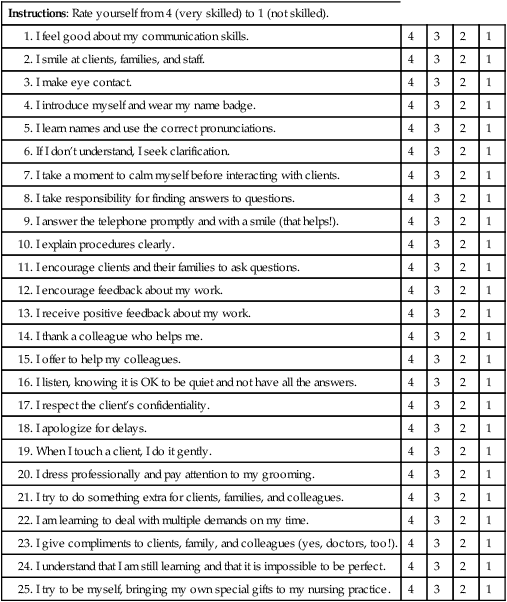

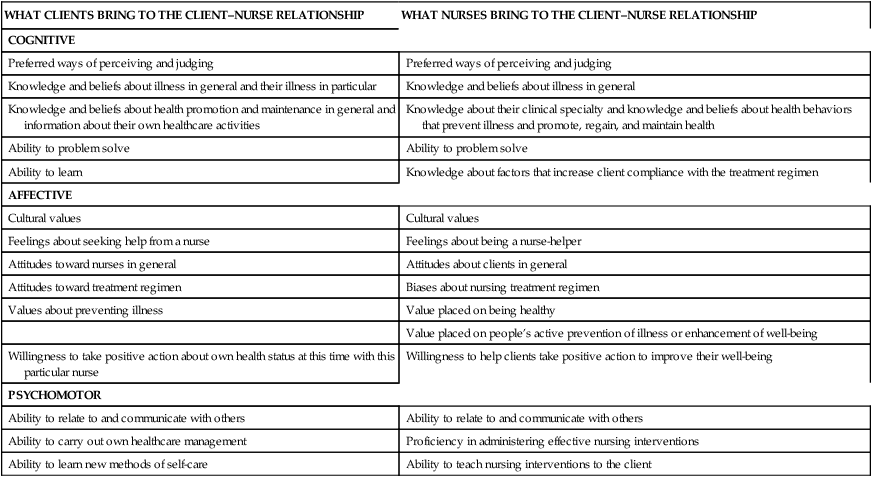

Chapter 2 1. Identify the purpose of the client–nurse relationship 2. Describe the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor abilities that nurses and clients bring to the therapeutic encounter 3. Discuss clients’ rights as consumers of healthcare service 4. Identify characteristics of a successful client–nurse relationship 5. Identify therapeutic communication techniques 6. Identify nontherapeutic communication techniques 7. List do’s and don’ts in the client–nurse relationship 8. Identify behavioral dimensions indicative of bonding in the client–nurse relationship 9. Identify qualities of a storycatcher 11. Participate in exercises to build skills in the client–nurse relationship “Friendly nurses seem like they know everything” is a telling quote from a participant in a study to examine clients’ perceptions of nurses’ competencies. Qualities such as cheerful, happy, and smiling created the impression that nurses were skilled (Wysong and Driver, 2009). Have you ever been in the patient role, vulnerable, unsure, frightened? A friendly word, a smile, a question about how you are feeling can reassure and calm you. Clients value interpersonal skills in nurses as highly as technical skills and want to be treated like a “real person” (Geanellos, 2004). Encounters we have with our clients can be caring and helpful or unfeeling and even harmful. As a compassionate and caring nurse, you will want your interactions with your clients to be helpful and pleasant. In this chapter you will learn how to build effective relationships with your clients. Nursing care is planned to meet an individual client’s unique needs and situation with respect for the patient’s and family’s goals and preferences. Nurses provide patient education so that clients have the information necessary to make informed decisions about their healthcare, health promotion, disease prevention, and attainment of a peaceful death. Nurses establish a partnership with the client and family and with other healthcare providers. Professional practitioners of nursing bear a responsibility for the nursing care that clients–patients receive as sanctioned by state nurse practice acts (American Nurses Association, 2004). Client–nurse relationships are entered for the benefit of the client, but such a relationship is more effective if it is mutually satisfying. Clients are satisfied when their healthcare needs have been met and they sense that they have been treated in a caring manner. Nurses feel a sense of accomplishment when their interventions have had a positive influence on their clients’ health status and when their conduct has been competent and caring. Client–nurse relationships may be a mutual learning experience, but in general the goals of therapeutic relationships are directed toward the growth of clients (Stuart and Laraia, 2005). Following are some of the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor abilities that clients and nurses bring to their therapeutic encounter. Table 2-1 further illustrates that both clients and nurses start with notions and expectations that will influence the course and outcome of their relationship. Table 2-1 Clients and nurses both know something about health and illness in general, and about the individual client’s health concerns in particular. Clients bring their model or world view; “the way they perceive life, events, people, and situations . . . communicate, think, feel, act, and react” (Erickson et al, 1983, p. 84) to the relationship. Clients have definite knowledge about what has made them ill and interfered with their growth and fulfillment. They also know “what will make them well, optimize their fulfillment and or promote their growth.” This knowledge is called self-care knowledge (Erickson et al, 1983). As nurses we want to help our clients access and use their self-care knowledge to achieve a greater state of health and well-being. Nurses have their own views, based on their knowledge and beliefs about what will help their clients. To prevent clients and nurses from operating in isolation or at cross-purposes, they must exchange essential information. In addition to having different ideas, clients and nurses also have preferred ways of observing their worlds and making decisions about what they see. Each of us has a preferred mental process—the one we have developed most highly, the one we use best—that forms the core of our personalities (Myers, 1998). Clients and nurses have different ways in which they prefer to use their minds, specifically, the ways they choose to perceive and to make judgments (Myers, 1998). Perceiving includes becoming aware of things, people, occurrences, and ideas. Judging includes reaching conclusions about what has been observed. Judging—the process of making decisions about the information collected through perception—is the other mental process in which clients and nurses may differ. Some persons have logical, orderly, analytical decision-making processes and treat the world objectively (Myers, 1995). Decision makers such as these prefer to fit all experience into logical mental systems. Myers called this preference thinking and said that these people make decisions based on critical analysis of facts, valuing fairness. Other clients and nurses prefer to tune into the subjective world of feelings and values. Myers called this preference feeling and said that these individuals make decisions by analyzing how they will affect people, valuing harmony. Each of us prefers one of these decision-making processes to the other (Myers, 1995). Consider the following situation to better understand the two judging processes. Clients and nurses who prefer a rational, objective way of making decisions would invite Jossie to consider all the facts and then make a logical decision based on them. They would look at the consequences of any decision Jossie might make and judge it using their head rather than their heart. They would be able to remain emotionally uninvolved. They have the ability to see the “long view” and would likely encourage Jossie to consider her future pragmatically and act on the most sensible choice (Myers, 1995). This glimpse at two different methods for using our minds alerts us to the misunderstandings that can arise in helping relationships. We cannot assume that clients’ minds are guided by the same principles as our own. Clients, their family members, and professional colleagues may reason in the same way that you do, or they may prefer using different ways of perceiving and judging. They may not value the things you value or show interest in the same things you do (Myers, 1998). We all use different combinations of perceiving and judging, and colleagues and clients with the same preferences are likely to be the easiest to like and understand. They will tend to have similar interests (because they share the same kinds of perceptions) and consider the same matters important (because they share the same kinds of judgment) (Myers, 1998). On the other hand, it will be harder to understand and predict the behavior of colleagues and clients whose perception and judgment preferences differ from our own. We are likely to take opposite stands on any issue with colleagues and clients who prefer different thinking processes (Myers, 1998). “The therapeutic nurse–patient relationship is a mutual learning experience and a corrective emotional experience for the patient. It is based on the underlying humanity of nurse and patient, with mutual respect and acceptance of ethnocultural differences” (Stuart and Laraia, 2005). If you would like to learn more about your preferences for perceiving and making decisions, as well as about other personality preferences, arrange with your school’s counseling or guidance department to take the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). The aim of the MBTI is to identify, from self-reporting of easily recognized reactions, the basic preferences of people in regard to perception and judgment (Myers, 1998). Learning about your own preferences will make you more aware of how your way of thinking influences your behavior in client–nurse helping relationships. The Keirsey Temperament Sorter provides similar content and is available online at www.keirsey.com or in his book (Keirsey, 1998).

The client–nurse relationship: a helping relationship*

Nature of the helping relationship

Cognitive, affective, and psychomotor abilities in the therapeutic encounter

WHAT CLIENTS BRING TO THE CLIENT–NURSE RELATIONSHIP

WHAT NURSES BRING TO THE CLIENT–NURSE RELATIONSHIP

COGNITIVE

Preferred ways of perceiving and judging

Preferred ways of perceiving and judging

Knowledge and beliefs about illness in general and their illness in particular

Knowledge and beliefs about illness in general

Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and maintenance in general and information about their own healthcare activities

Knowledge about their clinical specialty and knowledge and beliefs about health behaviors that prevent illness and promote, regain, and maintain health

Ability to problem solve

Ability to problem solve

Ability to learn

Knowledge about factors that increase client compliance with the treatment regimen

AFFECTIVE

Cultural values

Cultural values

Feelings about seeking help from a nurse

Feelings about being a nurse-helper

Attitudes toward nurses in general

Attitudes about clients in general

Attitudes toward treatment regimen

Biases about nursing treatment regimen

Values about preventing illness

Value placed on being healthy

Value placed on people’s active prevention of illness or enhancement of well-being

Willingness to take positive action about own health status at this time with this particular nurse

Willingness to help clients take positive action to improve their well-being

PSYCHOMOTOR

Ability to relate to and communicate with others

Ability to relate to and communicate with others

Ability to carry out own healthcare management

Proficiency in administering effective nursing interventions

Ability to learn new methods of self-care

Ability to teach nursing interventions to the client

Cognitive

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The client–nurse relationship: a helping relationship

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access