5. The back and lower limbs

This chapter will look at relevant anatomy, examination and injuries relating to the back and the legs. Rib injuries are also included here because of the physical nearness of the chest and the lower back: injuries to these parts do not have much else in common. As in Chapter 4, the spinal structures which are closely related to the limb, and which can give rise to symptoms there, will be discussed at the same time.

Minor injuries to the chest and back are common events. However, there are special difficulties in assessing patients who have symptoms in these areas: the decision that a patient has a minor injury essentially is a decision that the problem is musculoskeletal. It is easier to make that decision with confidence when a limb is injured because the limbs are almost entirely musculoskeletal structures. The trunk, on the other hand, houses most of the major organs and the sudden onset of pain, with or without other symptoms, can herald a serious and sometimes catastrophic illness. Equally, in the case of a low-level, grumbling, chronic discomfort, a minor, musculoskeletal cause rubs shoulders with malignancy and other unpleasant possibilities in the list of differential diagnoses. The best safeguard is always a clear history of injury where that can be obtained. Chest pain should never initially be ascribed to a rib injury unless that clear history of trauma is given. The history of a back pain is sometimes vaguer, and a patient with a genuine musculoskeletal problem may not have a clear history of injury, or may have severe pain after a relatively minor event. This means that you must begin your assessment by considering the possibility of illness as well as injury.

It is also the case that injuries to these areas can damage major organs. In the case of rib injuries, where we cannot do much for the ribs themselves except to let healing take its course, our main concern when we see the patient is to assess the underlying organs for signs of injury.

A further problem, which is characteristic of the assessment and the management of back pain, is that it can be very difficult to decide, by clinical examination, which particular musculoskeletal tissue is causing the patient’s symptoms. There are ways to reach an exact diagnosis, but they involve time and resources which are difficult to find in a clinical area and which will not bring value by changing the management of the problem. It is therefore common to manage back problems without addressing this question. This means that the process of assessing the patient tends to be much more about ruling out worrying diagnoses than arriving at a pinpoint selection of the injured tissue, and the advice and treatment offered to the patient are very generic. In cases where symptoms are not settling, where a more serious pathology or one which may require surgery, is suspected, a more precise diagnosis may be sought, but this is in a minority of cases.

Patients with back pain sometimes present to emergency areas with the fixed idea of having an X-ray. There is no indication for X-ray in an emergency area unless the patient has suffered an injury of sufficient severity to raise the possibility of damage to the lumbar spine or the pelvis. The spine is robust and a minor knock to a healthy individual will not cause that kind of damage. X-rays of the lower back and pelvis involve the risks of significant radiation exposure especially for younger patients.

The chest and upper back

This section deals with injured ribs. The only type of chest presentation which can be comfortably placed in the category of minor injury is that of a blunt injury to the ribs. Patients with penetrating injuries and patients with chest pain and no history of injury may be in serious danger.

Patients with blunt rib injuries may also be shown to have a severe injury and it is part of the routine assessment of every presentation to rule out the main concerns.

Anatomy of the thoracic cage

The ribcage is a box-like, bony and cartilaginous, protective structure for vital organs: heart, lungs, liver and spleen and the large vessels of the circulation. In cases of injury to the lower ribs, damage to the kidneys is possible. Like every musculoskeletal structure, it makes concessions to contradictory demands. It cannot be sealed off because its organs serve every part of the body. It cannot be completely rigid because it moves to allow breathing and contributes to the overall mobility of the trunk.

Spine

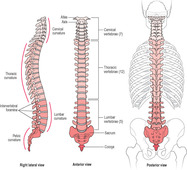

At the back, in the midline, lies the spine (Figure 5.1). There are 12 pairs of ribs, and each one of them articulates with one or two of the 12 thoracic vertebrae. The thoracic vertebrae are similar to the cervical ones, which were described in Chapter 4. They do not have the transverse foramina of the cervical vertebrae, which carry the vertebral arteries upwards from neck to brain, but they do have facets on the sides of their bodies for articulation with the ribs. The upper thoracic vertebrae are similar in size and appearance to those in the cervical area. They become bigger as they descend, making the transition to the lumbar region, where the vertebrae are large, adapted for bearing the weight of the entire upper body. The spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae are long and angled downwards.

|

| Figure 5.1 • |

Sternum

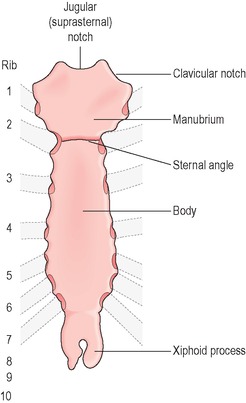

The sternum is the breastbone (Figure 5.2), a long, irregular plate of superficial bone which lies between the twin mounds of the chest in the frontal midline. It is made up of three bones, one above the other, linked by cartilage joints. The upper one is the manubrium (meaning, handle). Marieb (1995) describes it, very appropriately, as looking like the knot in a necktie. At the superior end of the manubrium is a hollow, plainly visible between the medial ends of the clavicles, the sternal notch, and there are two clavicular notches, divided by the sternal notch, for the clavicular articulations. At the widest part of the ‘knot’ are two articular facets for the costal cartilages (costa means rib) of the first ribs. The body, the longest part of the sternum, is joined to the lower end of the manubrium at the sternal angle. This is a hinge joint and forms a prominent, horizontal ridge on the upper sternum at the level of the insertion of the costal cartilage of the second rib. It is a useful landmark during examination. The body offers insertion points on each side for the second to seventh costal cartilages. The second costal articulations, at the sternal angle, are shared with the manubrium. The third to sixth articulations are notches along the sides of the body. The seventh is at the level of the xiphisternal joint, and the xiphoid process shares the articulations with the body. The xiphoid (meaning, sword) is a small process at the inferior end of the body which offers attachment to the diaphragm and to muscles of the abdomen.

|

| Figure 5.2 • |

Ribs

The ribs are bones which ossify from cartilage. They are long, flattened, curving and twisting, having approximately a C-shape when seen from above. They are angled downwards as they curve from the thoracic spine at the back to the sternum at the front. They are variable in appearance, depending on their position in the thorax. There are 12 pairs of ribs, and they form a cage, open at the top and bottom (the thoracic inlet and outlet), with horizontal bars which constantly separate and come together to allow the lungs to expand and to deflate. The intercostal spaces between ribs contain muscles, nerves and blood vessels. The intercostal muscles act to widen the spaces between ribs during inspiration. The intercostal blood vessels may cause a haemothorax if they are injured. A residue of hyaline cartilage is found at the front end of each rib. This costal cartilage links the first seven ribs to the sternum. The costal cartilage of ribs eight to ten merge with that of the seventh rib and are, therefore, only indirectly connected to the sternum. The cartilage of ribs 11 and 12 (short ribs, sometimes called floating ribs) merge with the muscles of the abdomen at the front and have no sternal connection. Typical ribs have at the back an area called the head; this has two facets for articulation with the sides of the bodies of two neighbouring thoracic vertebrae, the rib’s own vertebra and the one directly above.

The costal cartilage is covered with perichondrium, a tissue which blends with the periosteum of the ribs. The cartilage can be torn by injury without separation of this outer layer; consequently, there may be a deceptive appearance of integrity in a damaged structure.

Minor chest injuries

The usual mechanisms for blunt rib injuries are sport in the young and falls, especially in the intoxicated and the elderly. Typical tales are of a blow by an elbow or knee to the chest, a fall with the patient’s own elbow trapped against the ribs, a fall in a bath with the arm lifted so that the chest falls against the edge of bath or basin. Patients who have had a chest infection and have been coughing remorselessly will sometimes experience a sudden cracking or tearing in the chest; they will then have the typical pain of those with injured ribs. Assault with blunt objects is another source of rib injury, and you must exclude injury to the bony spine, the scapulae, the sternum and the clavicles (as well as other injuries).

The patient will localise a painful spot, which will be very tender. There may not be bruising. The patient may describe abnormal grating or clicking on breathing, and you may feel crepitus when the spot is touched. Crepitus can indicate a mobile fracture or a tear at the junction between the rib and its cartilage. There may also be surgical emphysema, a palpable crackling in the soft tissue caused by air from a pneumothorax.

Pain is a considerable feature of rib injuries. It is not usually present at rest but is triggered by deep breathing and coughing, and by certain movements. Sleep may be disturbed because it is hard to lie comfortably, and because movement in the bed hurts. Pain tends to worsen, or become more tiring, on successive days for a week or so, and patients will often present, or return, after a week of increasing difficulty, looking grey faced and weary.

The patient often asks for an X-ray. If the injury is not complicated by a severe or dangerous mechanism, the sternum and spine are not tender, there is no sign of injury to the organs and there are no medical factors, then X-ray findings on do not influence management. The usual practice is to treat the patient on clinical grounds alone. However, X-ray is indicated in some cases, and you must assess each patient fully.

History

Ask for general social information including occupation and hobbies, especially sports. A rib injury takes about six weeks to settle. It has adverse effects on movement of the trunk and arms, the ability to run, lift, climb ladders and many other activities. Consider the implications of the injury for the patient’s daily life and give advice on how the problem will change his routines for the next few weeks. He may also require a sickness certificate from his GP if he is absent from work for more than a week.

Ask if there is a history of respiratory illness, which may predispose to chest infection after a rib injury. Does the patient have any heart problems? Does he take oral steroids or warfarin? Is he a smoker; if so how much?

What was the mechanism of injury? Is pain is local to the injury. It is common for patients with rib injuries to feel an encircling pain from front to back on the same side as the injury. This reflects the shape and position of the injured rib. When did the injury happen? If the injury is days old, why has the patient come now? The patient may be needing help with pain control or may be developing a chest infection. Has the pain changed in location, severity or nature, or in the factors which bring it on? The pain can be severe even though the injury is not complicated in any other way. Does the pain feel as if it is on the surface, or deep, and does it radiate to neck or arm? Is the patient short of breath, as opposed to having pain when breathing deeply? Has he coughed or vomited blood? Does the patient feel unwell in any way: sick, dizzy or faint? Does the patient have any symptoms in the abdomen? Is there blood in the urine?

Examination

ABC: airway, breathing and circulation

Look carefully for any sign of a major trauma or illness. ABC describes the basic tenets of checking the airway, breathing and circulation.

Record the patient’s vital signs. Look for any systemic signs of lung injury, internal bleeding or chest infection. An accurate respiratory rate is required. Is there any clinical sign of excessive respiratory effort? Tachycardia and low blood pressure may indicate internal bleeding. If your area has a pulse oximeter, record the oxygen saturation. If the lower region of the ribs is involved, perform a urinalysis.

The patient’s trachea should be sitting in the midline of the front of the neck. Deviation of the trachea is a sign of a tension pneumothorax on the opposite side to the deviation.

Palpate the spine and the sternum. A transverse process is the most likely structure to be injured in the thoracic spine. The apex of the heart lies close to the sternum and a tender sternum may indicate not only fracture but injury to heart or its large blood vessels. If the sternum is tender the patient will require chest and sternum X-ray and an ECG.

Listen to the patient’s chest with a stethoscope for equal air entry to all lung fields, and any wheeze or moisture.

Look at the movement of the chest. Is there asymmetry? Are the ribs in the painful area moving with the others?

Stress the ribcage. If the injury is to the lateral part of a rib, compress the cage between your hands, placed over the sternum and the spine. If the injury is to front or back, press the ribs towards the midline, with hands placed at each side. This should elicit pain if there is a fracture.

Palpate the painful area for tenderness, the crepitus of broken ends of bone. If the injury is to the costochondral junction, tenderness will be felt at the junction of rib to cartilage. Palpate the abdomen and lumbar region. If the patient is tender or the abdomen is rigid, a doctor should exclude injury to liver, spleen or kidneys. The spleen is tucked under the costal margin on the left, and the liver on the right. The kidneys are in the lumbar region.

X-ray will normally be requested for a patient with a rib injury in the following cases:

• The mechanism has been severe, including falls from a height, road traffic accidents and injury involving great weight and force, such as may happen with industrial machinery. Such injuries will not normally present to minor injury areas.

• The patient seems to have a multiple rib fracture, or a severe osteochondral separation. Fractures to the first three ribs tend to be the result of a severe injury, and underlying complications are likely, especially injury to nerves and large blood vessels.

• There is any suggestion that the spine is injured.

• There is a possible fracture of the sternum.

• There is any suggestion of a haemo- or pneumothorax, or contusion of the lung.

• There is a history of respiratory illness, or the appearance of respiratory complications. A patient would not necessarily have an X-ray because there seems to be a chest infection. If the patient has no long-standing medical problems, it may be most appropriate to refer to the GP.

• The patient is elderly.

Other forms of imaging are appropriate for patients when you suspect injury to the liver, spleen or kidney Refer the patient to the appropriate specialist (often a surgeon) in your area.

Treatment

Rib injuries are not strapped.

The patient will need pain killers. Ibuprofen in combination with paracetamol is often the treatment of choice if the patient has no gastric or renal problems and does not suffer from asthma. Pain is a problem for rib-injured patients, and you may see someone who has already tried everything that the minor injury clinic can offer. Refer these patients to their GPs.

The patient should be told to incorporate several sessions of deep breathing and forced coughing into the routine of pain relief. The injured site is supported with the hands while the patient inhales deeply and breathes out slowly; this is repeated several times, and then the patient should cough. This procedure is repeated at least six times per day; it will hurt, but it helps to avoid a chest infection. Smoking should be kept to the minimum.

The first 1 or 2 weeks will be the most painful. The patient may have to take time off work and will certainly not be fit for heavy exertion for possibly 6 to 8 weeks. The GP can issue sickness certificates.

The patient who has a discoloured sputum or is feverish should see the GP. However, if the patient develops haemoptysis he should go to A&E.

The lower back

Pain in the lower back is rather like the common cold, universal but poorly understood and a source of frustration and misunderstanding between health professionals and patients. This section focuses on the distinctions between emergencies where back pain is a symptom, serious and less-serious neurological presentations, and so-called simple or mechanical back pain. Current guidelines for the treatment of back pain are discussed.

You will usually refer patients who present with abdominal pain to a doctor. Genuine minor injury presentations with abdominal pain as a main symptom are unusual.

Anatomy of the lumbar spine

The general structure of vertebrae, the arrangement of spinal ligaments and the way in which spinal nerves emerge from the vertebral column is discussed in Chapter 4. Articulation between the lumbar vertebrae occurs in the same manner as in the higher vertebrae:

• between intervertebral discs and vertebral bodies

• between two facet joints on the inferior aspect of the upper vertebra, and two facet joints on the superior aspect of the one below.

There are five lumbar vertebrae (Figure 5.1); these are chiefly distinguished from the higher vertebrae by their adaptation for weight bearing. They are large, and their facet joints are directed so that they limit rotation at the lumbar spine (most of the rotation which can be achieved in the trunk occurs in the thoracic spine) for the sake of stability (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1

• Capsular pattern equal restriction of side-flexion and rotation, and a lesser degree of loss of extension.

• Joint positions close packed is full extension, when the facets meet; loose packed is halfway between flexion and extension.

• Flexion up to 60°; endfeel is firm, ligament and facet joint capsules.

• Extension up to 35°; endfeel firm; the posterior bony surfaces meet and the anterior disc, ligaments and muscles are stretched.

• Rotation up to 18°; endfeel firm; movement is ended by ligaments and articular processes.

• Side-flexion up to 20°; endfeel is firm, restricted by the ribs (the facet joints coming together) and stretching of the joint capsules.

The spinal cord is shorter than the vertebral canal and ends at the level of the first lumbar vertebra. From there, the nerves, which pass out through the intervertebral foramina of the various lumbar vertebrae, pass down the canal to their exit points as a collection of long strands, called the cauda equina (horse’s tail).

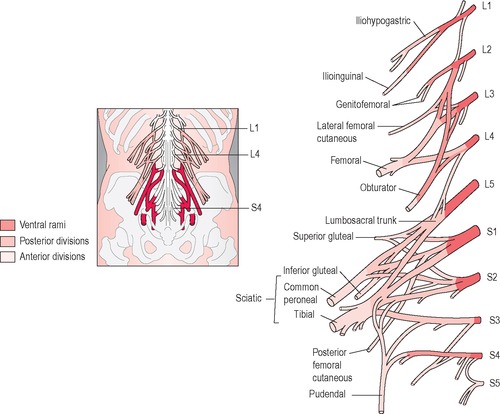

The ventral nerves from L1 to S4 supply the leg. As at the neck (see the brachial plexus; Figure 4.4), these nerves form networks which permit the exchange of fibres between nerves emerging from the spinal cord and forming peripheral nerves in the limb. There are two networks which are relevant here: the lumbar plexus and the lumbosacral plexus (Figure 5.3).

|

| Figure 5.3 • |

The lumbar vertebrae rest upon, and articulate at L5, with the superior surface of the sacrum, a wedge of bone which links the two posterior segments of the pelvis at the sacroiliac joints. The sacrum is the superficial bony surface which can be felt in the midline of the buttocks, just above the cleft. It is considered as a single unit, but it actually comprises five fused vertebrae. It combines three roles. It is the base upon which the vertebral column is stacked, it is the link between the spine and the pelvis, and it is one of the unifying elements between the two halves of the pelvic girdle.

The vertebral canal continues down into the sacrum as the sacral canal. On the front surface of the sacrum, there are four transverse lines, which mark the fusion of the sacral vertebrae; there are holes at each end of these ridges, sacral foramina, which allow the passage of nerves and blood vessels. On the dorsal, convex surface of the sacrum, there is a raised, vertical ridge in the midline; this is the vestige of the spinous processes and is called the median sacral crest. The ridge is incomplete. The fourth and fifth spinous processes are absent, and, at that part of the midline, there is a small opening, the sacral hiatus, which gives access to the sacral canal at its inferior end.

The sacroiliac joints are synovial joints, only slightly moveable, between the sacrum on each side and the articular surfaces of the ilium on each side. These joints close the ring of the pelvis at the back. They are reinforced by interosseus ligaments at the back and front. The posterior ligaments may be torn by injury during the movement of bending forward at the waist.

The sacrum has a small bony tail, the coccyx, made of four or five more vertebrae, also fused. The coccyx has no distinct function. It is palpable as a rough, superficial bony surface, just above the anus.

The patient with back pain

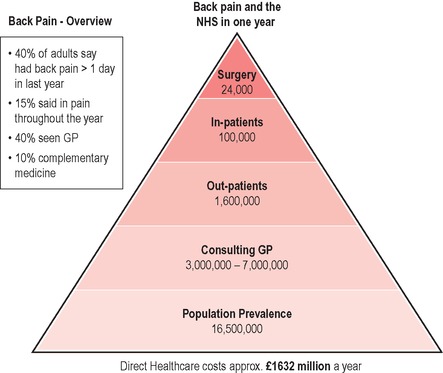

Back pain is a problem of serious and increasing significance for sufferers, their families and for society at large. In the UK, the number of days lost at work because of back pain increased from 15 million in 1970 to 106 million in 1994 (Burn 2000). Many people who suffer from chronic back pain give up their work for good, which is a drain on the health and social security systems and a cause of misery for the individuals and their families (Figure 5.4).

|

| Figure 5.4 • |

Assessment

The assessment of a painful back can be divided into three stages:

• Exclude a ‘red flag’ emergency

• Exclude illness rather than injury

• Exclude a neurological rather than mechanical cause for the pain.

It is important that two emergencies are excluded in patients with back pain: lumbar disc prolapse, which threatens the nerve supply to bladder and bowel, and an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The patient with a disc prolapse compressing the spinal cord at L1, or the cauda equina in the lower lumbar region, may suffer irreversible damage, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most useful investigation to exclude that diagnosis. The patient may complain of bilateral leg pain (most commonly radiating down the backs of the thighs), paraesthesia and weakness, perianal paraesthesia (in the so-called saddle area), a loss of tone of the rectal sphincter, and, possibly, a loss of bowel control or retention of urine (with overflow as the problem progresses). The patient may need emergency surgery (an assessment that would be made by a neurosurgical or an orthopaedic specialist, depending on local arrangements).

A patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm may present with back pain, which will not be in the pattern of musculoskeletal injury. It will be constant and probably worsening, not improved by a change in position, no better at night. It may radiate into the groin and thigh. There may be a swelling in the abdomen, the classic pulsatile mass. This condition is most common in men in later middle age. If this diagnosis is suspected, the patient should be referred as an emergency. The aneurysm may rupture at any time, even if the patient seems well at the moment. Always include an assessment of the patient’s abdomen in your examination of a painful back.

If a patient has suffered a violent mechanism of injury, such as a road traffic accident or a fall from a height, he will not be managed as a minor injury. The patient may have rupture of internal organs, with heavy bleeding or spinal, pelvic or hip injuries. Assess (and constantly reassess) in terms of resuscitation and ABC; the patient may require spinal board immobilisation and emergency ambulance transfer.

There are other medical problems, including neoplasm, osteomyelitis, osteoarthritis and infections of the genitourinary and gastric tracts, which may cause the patient to present with back pain. There will be no history of injury, the pattern of pain will not be musculoskeletal, and there may be other systemic signs, such as a raised temperature. The patient may have a history of previous cancer, of recent weight loss or may feel generally unwell. The older patient should be considered as at a higher risk.

In any case where there is doubt, refer the patient.

Common patterns of back pain

For all that the problem is common and increasing, the causes of, and predisposing factors for, back pain are not well understood. The guidelines which are current for the treatment of patients with back pain do not concentrate on precise diagnosis. The objective is to recognise patterns of presentation, and patterns of outcome, and to make a correct assessment of the type of problem, so that the patient is guided along the path which appears, from other patients’ experience, to offer the best hope of recovery.

The urgent and serious conditions have been discussed above. Among the less serious, more common presentations, there are two large categories:

• main symptom is pain radiating down one leg

• main symptom is pain in the lower back with no significant radiation to the leg.

The first of these is less common than the second (less than 5% of all patients with back pain according to Burn, 2000). The pain which is referred down the leg because of pressure on a nerve root will follow a dermatomal pattern and will be triggered or increased by a specific test for stretching the nerve (the sciatic stretch (see Figure 5.5 and Box 5.2).

The first of these is less common than the second (less than 5% of all patients with back pain according to Burn, 2000). The pain which is referred down the leg because of pressure on a nerve root will follow a dermatomal pattern and will be triggered or increased by a specific test for stretching the nerve (the sciatic stretch (see Figure 5.5 and Box 5.2). |

| Figure 5.5 • |

Box 5.2

• A passive straight leg raised above 75° will cause pain and paraesthesia in the leg if there is a disc protrusion at L4 to S1.

• To ensure that pain is caused by sciatic nerve, and not hamstring stretch, lower leg slightly until pain stops, then dorsiflex the foot.

• The test is positive if the pain returns.

The second major category of back pain sufferers includes patients who may have pain which radiates to the upper part of the leg (not below the thigh), in a non-dermatomal pattern; this pain does not have a neurological origin. This group, the larger by far, is suffering from simple or mechanical back pain. The pain is triggered by lifting or bending, and there may be either a sudden severe pain or a gradual onset. If the patient experiences muscle spasm at the time of the injury, the back may ‘lock’ in lumbar flexion. The pain may be felt on one or both sides of the lower back. There may be radiation of pain to the upper part of the leg but not to the foot. The pain will have a musculoskeletal pattern, being aggravated by physical activity and relieved by rest, especially by lying down.

Examination

History

‘Simple back pain’ is a broad diagnosis, partly arrived at by a process of elimination. The history plays a large part. The patient’s age, gender, occupation and general lifestyle will have great bearing on the possible diagnoses and the priorities of treatment.

Treat young patients and those over 55 years of age with care. These groups are at higher risk of non-musculoskeletal causes for their back pain.

Establish a mechanism of injury. There may not have been a severe force, but the patient will probably recall a recent exertion or may say that the pain began while bending forward. In most cases, there will be some pain at the moment of injury, even if it does not become troublesome until later.

Assess the pattern of pain, its relationship to movement, relieving and aggravating factors, the effects of the pain on sleep, whether it is worse in the morning. Coughing tends to aggravate the pain caused by a lumbar disc prolapse.

Ask about severity of the pain, and whether or not it developed suddenly. Ask where the pain is felt, and whether there is radiation of the pain. If there is pain in the leg, ask if it is more severe than the back pain, which tends to be the case with sciatic pain, and map its pathway on the leg. Ask if there is numbness or tingling.

Ask if the patient feels well, apart from the back pain. Ask about any other symptoms: chest pain, abdominal pain, bilateral leg pain, any weakness or paraesthesia, coordination problems, change in bowel or bladder habit.

Obtain a full medical history, including medications and allergies; ask if the patient is taking steroids. Has the patient any history of arthritic disease? Has the patient had any surgery?

Consider medical referral if there are any atypical features, if the patient is describing severe symptoms, or if the history suggests an illness rather than an injury.

Look

The patient’s ability to stand up and sit, the pattern of walking, the posture and the ability to perform simple tasks, such as tying shoelaces, will give an impression of the pattern of disability and the severity of symptoms. Is the patient limping? The pain and the fatigue which simple back pain causes can be considerable.

Ask the patient to undress and observe the back and the legs. The patient may have a scoliosis, a lateral curvature of the spine. Scoliosis may exist for different reasons, such as the need to compensate for the angled pelvis which results from having unequal leg lengths, but it may be an acute response, an attempt to relieve the pressure on a compressed nerve root. Look at the pelvis. Is it tilted? You may assess this by checking the levels of the posterior superior iliac spines.

It may be possible to see, on one side of the lumbar spine, the contracted mass of erector muscles of the spine in spasm.

Feel

The lumbar spine is best palpated with the patient prone on a couch. The spinous processes are easy to feel, but the transverse processes may be fairly deep in the erector muscle bulk. Muscle which is in spasm may be both visible and palpable.

Move

Move

Active movement in the back is assessed as:

• the range of movement

• the rhythm of movement

• whether or not there is pain on movement.

Test the lumbar spine in flexion, extension and rotation (Figure 5.6 •, Figure 5.7 • and Figure 5.8 •). Perform the sciatic nerve stretch test (Figure 5.5). The straight leg raising test is the most valuable, because it stresses the nerves and their roots from L4 to S1, which are the most likely to suffer the effects of a disc prolapse.

|

| Figure 5.6 • |

|

| Figure 5.7 • |

|

| Figure 5.8 • |

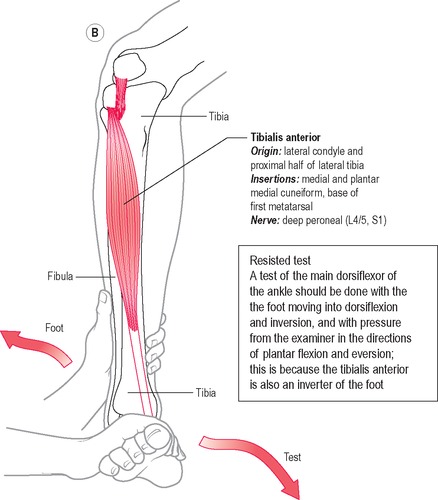

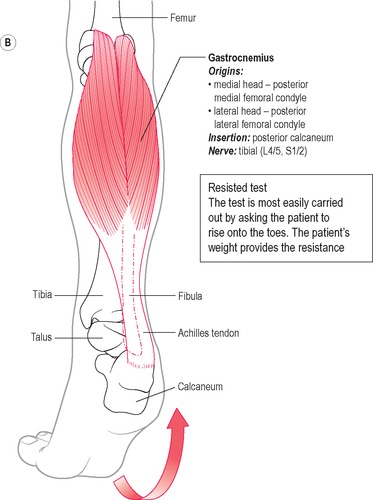

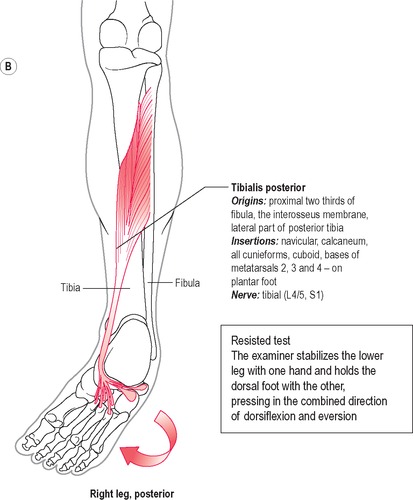

Assess sensation in the legs in all dermatomes and map any deficit. Motor power in the legs can be assessed, using resisted tests (illustrated in later sections covering joints of the leg) for the following muscles:

• L2: hip flexion (iliopsoas; see Figure 5.11 below)

• L4: ankle dorsiflexion and inversion (tibialis anterior; see Figures 5.31 and 5.32 below)

|

|

| Figure 5.32 • |

• L5: big toe extension: the patient is asked to dorsiflex the foot and extend the big toe while resistance is offered on the dorsal side of the foot in the direction of flexion of the big toe

• S2: toe flexion (flexors digitorum and hallucis longus): ask the patient to flex the toes and apply resistance on the plantar side of the foot, in the direction of extension.

Test reflexes at the patella and Achilles tendons (see p. 216).

In any case where there is doubt about cauda equina syndrome the patient will require a per rectum examination to establish that the anal sphincter has good tone. Ask the patient to squeeze the examiner’s finger by clenching the buttocks.

Treatment

Refer the patient to a GP if he needs more help with analgesia than you can give. Simple back pain can be severe.

Patients who have sciatic pain should be referred to GPs as long as they have no evidence of weakness or loss of sensation and reflexes are normal. The problem may not be quick to settle, adequate pain relief will be needed and, in a few cases, the patient may need orthopaedic treatment.

Current thinking on the treatment of simple back pain emphasises two priorities: remain mobile and stay at work. The GP is seen as the lynchpin of management of the condition. Bedrest should be kept to a minimum (ideally, not more than 2 days while the pain is too severe for any other course), except in the case where the pain arises from nerve root problems. Physiotherapists, chiropractors and other specialists in manipulation should be involved if the problem does not settle within a few days. The management of patients with sciatic pain should differ in the length of time spent in bed (up to 2 weeks), but in other ways, the principles are the same as for simple back pain. The patient should move on to a programme of active exercise as soon as possible and should stay at work if possible.

There is a large role for health promotion for patients with back pain. The condition can be recurrent, disabling and depressing. Subjects such as safe lifting and the value of exercise to prevent injuries and help recovery are very important.

Muscle spasm causes troubling symptoms for sufferers from back pain. On occasion drugs such as diazepam are prescribed if the symptoms are not settling. This would not be the first resort. Muscles which are in spasm are in a protracted state of contraction as a protective reflex to guard the injury. The muscles cannot perfuse themselves adequately in this condition, and the patient cannot move properly. Two simple tactics can help. The muscles will relax if they are rested from their normal activity. For a patient with back pain this means lying down. The use of heat applied locally increases blood flow to the area and encourages the spasm to relax and perfuse itself. Heat should be used with care: the situation will not be improved if the skin is burned.

The hip

Anatomy

The pelvic girdle relates to the leg as the shoulder girdle does to the arm (Figure 5.9). The pelvis is also a bilateral and symmetrical structure which connects limb to trunk. It has articular sockets for the heads of the femur. The hip joints are synovial capsules with ligament and muscle reinforcement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access