Chapter Five. Tackling health inequalities

Key points

• Definition and scope of inequalities

• The link between social and health inequalities

• Tackling inequalities: policies and strategies

• Tackling inequalities: the practitioner’s perspective

• Evaluating what works to reduce inequalities

OVERVIEW

‘Health inequalities’ is the phrase used to refer to patterned socio-economic differences in the health status of populations. People with a lower level of education, lower occupational class or lower level of income tend to die at a younger age and have a higher prevalence of all kinds of health problems. Whilst differences in people’s health are unavoidable and natural, structured differences that are related to socio-economic factors are deemed to be unjust and inequitable. Despite high levels of prosperity and developed health and social care systems, inequalities have increased in the last 20 years in many countries. Inequalities in social circumstances are linked to inequalities in health via a variety of mechanisms. Whilst there is debate concerning the magnitude of effect of different factors, material disadvantages, such as low income, are generally viewed as central. Other key factors are environmental, such as poor housing and low levels of social support; psychosocial, such as low self-esteem and chronic stress; and accumulated disadvantages experienced during the life-course or concentrated into particular geographical areas (Brunner and Marmot 1999; Wilkinson 1996). Factors other than social class (such as gender and ethnicity) that show patterned associations with health status are generally perceived to be linked to health via material circumstances and income, although cultural norms and lifestyles are also involved.

The documented rise in social inequalities in the UK since the 1970s and 1980s has been mirrored by a growth in health inequalities (Acheson, 1998 and Shaw et al., 1999). The UK Labour government recognized inequalities in health as a major public health issue. In 2001, two targets to reduce inequalities in infant mortality and life expectancy were set, and there has also been ongoing consultation and debate around strategies and policies to tackle inequalities and how these should be evaluated (Department of Health (DoH), 2001, Department of Health (DoH), 2004, Department of Health (DoH), 2005 and Department of Health (DoH), 2008a).

This chapter reviews the evidence of widening social and health inequalities and then goes on to look at the mechanisms which link social and health inequalities. The current policy context is briefly reviewed, demonstrating a supportive environment for tackling inequalities. Strategies to enable practitioners to tackle health inequalities are discussed, using several examples of innovative work in this area.

Introduction

For those working to promote health, recognition and understanding of the social structural factors that underpin health experiences and health status are fundamental. Practitioners work with individuals and communities, but underpinning the experience of clients are basic social structures such as income distribution, education provision, employment prospects, and housing access and affordability. These basic social determinants of health are discussed in detail in Chapter 9. One of the key characteristics of these social structural factors is their non-egalitarian and inequitable distribution both worldwide and within different countries. For health practitioners, the link between social and health inequalities is central. Whilst it may appear at first sight to be impossible to address such structural causes of health inequality, this chapter argues that practitioners do have the potential to intervene successfully to address inequalities in health. Practitioners may feel that addressing poverty or unemployment is potentially stigmatizing and victim-blaming and therefore avoid such topics. The good practice examples in this chapter demonstrate how tackling inequalities can be undertaken in a constructive, empowering and health promoting manner.

Defining health inequality

Inequalities refer to differences in circumstances, or the state of being unequal. The current usage of this term in public health includes the additional element of inequity, or being unjust or unfair:

The term inequity has a moral and ethical dimension. It refers to differences which are unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are also considered unfair and unjust … Our aim is not to eliminate all health differences, for that would be impossible, but rather to reduce or eliminate those that result from factors which are avoidable and unfair … Equity in health implies that ideally everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and, more pragmatically, that no-one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential if it can be avoided.

‘Inequalities’ is the common term used in the UK, but other countries use the terms ‘inequities’ or ‘disparities’ to refer to the same phenomenon. There are different types of inequalities in health, including:

• socially patterned differences in life expectancy

• socially patterned differences in health and ill health (both acute and chronic) status

• inequalities in access to, and use of, services

• geographic or regional differences

• differences in treatment outcomes.

My case-load spans a deprived inner city area and a more affluent adjacent area. There’s more health problems in the inner city area, granted, but there’s also health problems in the affluent area, and there are plenty of perfectly healthy people living in both areas. Everyone’s health is different, you can’t expect it to be otherwise. We need to make sure that everyone can get the services they need but that’s about all we can do.

Commentary

It is unrealistic to expect everyone to have equal income or health. Some factors (e.g. gender, ethnicity, age) are clearly unalterable and may include a biological dimension that impacts on health. Some practitioners may argue that other factors such as education or employment include an element of individual choice, although this is debatable. Being unemployed may be a result of a lack of training and employment prospects, determined in turn by wider economic factors such as recession. Even where it appears that there is an element of individual choice (as in behaviours such as smoking), social norms and networks will, to a large degree, determine lifestyle choices. As Dr. Chan (2008) put it: ‘Lifestyles are important determinants of health. But it is factors in the social environment that determine access to health services and influence lifestyle choices in the first place’. This is why such factors are socially patterned rather than randomly distributed. There are variations in health but their social patterning rather than random distribution makes them unjust.

Equity, or social fairness and justice, is an acknowledged goal of many health services and interventions. Equity is not the same as equality, or everyone being equal, which is clearly unrealistic in relation to people’s health status. People have varying degrees of health, but the goal of health equity is the absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in health among social groups (Solar and Irwin 2007). Public health and health promotion strategies may improve health overall but at the same time actually increase inequalities as the better off are more likely to access services or adopt health messages (Kelly et al 2006). In 2002, the NHS foregrounded equity by adopting tackling health inequalities as a key priority area (DH 2002).

The scale of inequalities

Inequalities in health are apparent worldwide as well as being manifest within countries. Today the life expectancy for a child born in Japan or Sweden is more than 80 years; for a child born in Brazil it is 72 years, for a child born in India it is 63 years, and in several African countries it is less than 50 years (CSDH 2008). The following example demonstrates how globalization may reinforce and magnify inequalities rather than tackle and reduce them. Globalization may also impact on inequalities through factors associated with economic growth and development, such as the loss of diverse natural habitats, the risk of pollution, and the vulnerability of single crop economies to infestation or disease.

Global inequalities in health

In Britain, 1 child in every 150 dies before the age of 5. Average per capita spent on health is £927. In Ghana, 1 child in 10 dies before the age of 5. Average per capita spent on health is £6. In addition, Britain has saved £65 million in training costs by recruiting Ghanaian doctors since 1998, whilst Ghana has lost £35 million of its training investment in health professionals (Ray 2005).

Within many countries, including the UK, the USA, the Netherlands and India, there is a wealth of evidence documenting the continued existence of health inequalities (Acheson, 1998, Department of Health (DoH), 2005, Dorling, 2006, Groffen et al., 2008, Lantz et al., 2001, Office of National Statistics (ONS), 2004 and Subramanian et al., 2006). Box 5.3 gives a summary of this evidence for the UK, most of which focuses on social class or socio-economic status, as measured by the Registrar-General’s occupational classification system, as the key variable. In 2001, the old classification of 5 categories was replaced by the NS-SEC (National Statistics Socio-economic Classification). The NS-SEC has 8 categories, including a new category (8) for ‘never worked and long-term unemployed’. This issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2 in our companion volume Foundations for Health Promotion (Naidoo and Wills 2009). Other forms of inequality linked to factors such as geographical area, gender and ethnicity, and the ways in which inequalities accumulate over the life-course, are also the focus of considerable research (Graham 2000).

Box 5.3

Health inequalities in the UK in the twenty-first century

• The social class difference in life expectancy is around 9 years for men and 5 years for women (ONS 2007).

• In 2001–2003, the infant mortality rate (IMR) for the ‘routine and manual’ group was 19% higher than for the total population, which was an increase compared to the 13% difference between the two groups in 1997–1999 (DH 2005).

• Babies of unskilled manual workers are almost three times more likely to die than babies with fathers in professional occupations. In England and Wales in 2002 the estimated IMR among children whose fathers were in higher managerial and professional occupations was 3.1 per 1000 live births compared to 9.2 for children whose fathers were in routine and semi-routine occupations (ONS 2004).

• The IMR for babies of mothers born in Pakistan is almost double the overall IMR (DH 2006)

• Material disadvantage is an independent risk factor for disability in older adults. The most disadvantaged groups are 2.5 times more likely to report severe disability than the reference group (Adamson et al 2006).

• Death rates from circulatory disease are over 25% higher in the North West than in the South West of England (DH 2006).

• The life expectancy for men in Blackpool is 8 years less than for men in Kensington and Chelsea (DH 2006).

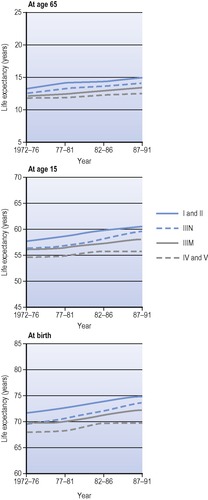

In the UK, socio-economic differences in life expectancy have proved to be a persistent trend, with people in social class group 1 enjoying longer life expectancy than those in lower social class groups. These socio-economic differences increased from the 1970s to the mid 1990s, when the difference peaked at 9.5 years for men and 6.5 years for women (see Figure 5.1). Since then socio-economic differences have declined slightly, but remain very significant.

|

| Figure 5.1 • Male life expectancy by social class, England and Wales. Source: Drever and Whitehead (1997). |

There is a noticeable stepwise gradient of health outcomes across all socio-economic groups. Higher socio-economic status is linked to increased longevity, reduced incidence of premature mortality at all ages, and reduced incidence of ill health and disease. There are a few exceptions to this rule (e.g. some cancers, hypertension, type 1 diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis), but the overall pattern is consistent and marked (Asthana and Halliday 2006).

Socio-economic differences in mortality are most marked amongst children, young people and younger adults, although they persist into older age groups as well. The infant mortality rate (IMR) is also patterned by socio-economic status. Morbidity is also affected by socio-economic status. Whilst it may be no surprise that social class group 8 (never worked and long-term unemployed) experience five times as much long-term illness as social class group 1, long-term illness is also twice as common in social class group 7 (routine occupations) compared to social class group 1 (ONS 2001). Many other illnesses (although not all) are more common amongst lower socio-economic groups (Asthana and Halliday 2006).

Whilst the link between socio-economic status and health is strongly documented, there is also evidence that geographical area, gender and ethnicity are also linked to health status. In the UK, there is a big North–South divide with higher rates of poor health found in Wales, the North East and North West regions of England than elsewhere. The widest health gap between social classes, however, is in Scotland and London, illustrating some of the complexities of area-based strategies and resource funding (Doran et al 2004).

Gender differences and inequalities, especially in relation to income, may result in inequalities in health status and access to health care. In terms of gender differences in health status, women tend to live longer than men, but experience more ill health and make more use of health services such as GPs than do men. Commentators (Daykin, 2001 and Doyal, 1995) suggest no single cause but a combination of factors including continued gendered inequalities in society (e.g. the fact that women bear most of the burden of caring and domestic work and are discriminated against in the paid employment sector) and cultural stereotyping (e.g. doctors’ readiness to interpret women’s symptoms as evidence of mental illness).

The links between ethnicity and health are complex, with some evidence of better than average health status (e.g. low mortality from cancers amongst people from the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent) but a general pattern of poorer than average health status. There is excess mortality among migrant ethnic minority groups with higher rates of infant mortality, especially among babies of Pakistan-born mothers (Davey Smith et al 2002), and a more common perception of poor health among minority ethnic groups. Material factors, including poorer living circumstances and institutional racism and discrimination, make a central contribution to these findings (Bhopal 2007). Public services may be more punitive to people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups (BAME). For example, rates of compulsory detention under Part 11 of the Mental Health Act 1983 for BAME people are six times the rate for white people (Audini and Lelliott 2002). Chapter 12 discusses the benefits and challenges of targeting sections of the population who experience health inequalities, such as women and BAME.

Explaining health inequalities

There are five main theories proposed to explain socio-economic inequalities in health (Davey Smith 2003; Kelly and Bonnefoy 2007):

• Materialist/structuralist theory suggests that low income leads to a lack of resources which in turn leads to ill health.

• Social production of health model suggests that capitalist processes of wealth accumulation are achieved at the cost of the disadvantaged, who become socially excluded.

• Psychosocial model suggests that social discrimination based on one’s position in the social hierarchy leads to a biological response in the neuroendocrine system that in turn leads to disease.

• Ecosocial theory brings together the psycho-social and social production of health models and suggests that social and physical environments interact with individual biological systems.

• Life-course model proposes that the accumulated disadvantages experienced throughout the life-course or through generations has an impact on health.

Smoking is the biggest single cause of the differences in death rates between rich and poor people, and accounts for half the difference in death rates between men in the top and bottom social classes (Jha et al 2006). Which of the following views comes closest to your own?

• ‘Poor people bring illness upon themselves. They don’t care about their health, they smoke and drink too much and eat junk food. They could spend the money on healthy activities if they really wanted.’

• ‘People’s use of tobacco and alcohol is to a large extent determined by their social relations and social networks, which in turn affect their self-esteem and levels of stress. When social support is poor, tobacco and alcohol offer a prop of sorts.’

Adverse socio-economic circumstances and the unequal distribution of income are the key contributors to inequality. Poverty and its links with health and illness are discussed in more detail in the section on poverty and income in Chapter 9. Poverty may be defined in different ways. Objectively poor people are defined as those living in households with incomes below 60% of the median income level of that year, taking housing costs into account. Poverty may lead to an inability to access the essentials for healthy living (e.g. a warm and safe living environment, adequate nutrition).

But poverty may also be defined relatively, in terms of social expectations, resources and activities. There is a strong relationship between being poor, being unemployed, having few social contacts or support, and having little say in decisions affecting one’s life. The term ‘social exclusion’ has been defined as the state of being unable, because of low income, to participate in many of the activities which society regards as normal or appropriate (Social Exclusion Unit 1997). Social contacts are reduced, the pursuit of individual interests is likely to be impossible, and choices are severely constrained. In a sense, poor people become socially excluded second class citizens, without the resources to enjoy what constitutes everyday life for most people.

Social exclusion is not synonymous with poverty and includes a number of characteristics that are not always included in the concept of poverty. The concept of social exclusion implies exclusion from something – typically ‘normal society’. As we have seen in Chapter 4, policy interventions are underpinned by clear moral values. Those not working, for example, are seen not only as excluded but also dependent, irrespective of whether or not employment is desired (as may be the case for mothers in two-parent households). Voluntary self exclusion (as in some rough sleepers) may be seen as undesirable and demanding intervention. The ways in which socially excluded groups are targeted for specific interventions are discussed in Chapter 12.

Affluent countries with unequally distributed resources have populations with poorer health status than countries with equal distribution of resources (Wilkinson 1996). Conversely, poor countries or areas with egalitarian resource distribution mechanisms and policies experience better than expected health status. This is illustrated by the example of Kerala in South India. Mortality rates in Kerala are close to those of much wealthier, industrialized countries, and very different from other states in India. Kerala has redistributive policies and many years of investing in human resources, particularly promoting women’s access to education (Lynch et al 2000). Wealthy countries with redistributive policies, for example Nordic countries, Belgium and Japan, have the healthiest populations.

The psychosocial model proposes that the perception of inequality and disadvantage is mediated by biological processes that lead to poorer health outcomes. It is not so much the stark lack of resources, as the perception of something lacking that other people have, that is responsible for this process, producing a stress response:

The power of psycho-social factors to affect health makes biological sense. The human body has evolved to respond automatically to emergencies. This stress response activates a cascade of stress hormones which affect the cardio-vascular and immune systems. The rapid reaction of our hormones and nervous system prepares the individual to deal with a brief physical threat. But if the biological stress response is activated too often and for too long, there may be multiple health costs. These include depression, increased susceptibility to infection, diabetes, high blood pressure and accumulation of cholesterol in blood vessel walls, with the attendant risks of heart attack and stroke.

The ecosocial model states that it is the interdependent action and effect of many different determinants of health (including environmental, social and physical) that leads to health inequalities. This model flags up the need to address these different domains simultaneously in order to reap the most rewards. What is needed is joined-up thinking and action across the different domains.

The life-course model proposes that the clustering of advantages and disadvantages across the life-course and through generations is the key to health inequalities. This model shares many features with the ecosocial model, but includes a timeline. Deprivation experienced in utero or as a child has a biological effect (e.g. on height, weight, lung function) that impacts on a person’s health in later years: ‘Human bodies in different social locations become crystallized reflections of the social experiences within which they have developed’ (Davey Smith 2003, p. xlvii).

It appears that a number of factors are responsible for these patterned inequalities in health, including poverty, social exclusion, cultural stereotypes, and professional and institutional inflexibility. Poverty is not the only explanation for observed socio-economic, gender and ethnic inequalities, but it plays a central role.

Tackling inequalities

It is clear that inequalities in health are not just a consequence of health service delivery but have complex origins in socio-economic conditions, living and working conditions, and people’s lifestyles. The implications of this are that tackling health inequalities involves all sectors of society:

the high burden of illness responsible for appalling premature loss of life arises in large part because of the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. In their turn, poor and unequal living conditions are the consequence of poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics. Action on the social determinants of health must involve the whole of government, civil society and local communities, business, global fora, and international agencies. Policies and programmes must embrace all the key sectors of society not just the health sector.

Strategies for tackling health inequalities focus on four main areas:

1. Macro-economic social policies (such as reducing unemployment levels).

2. Living and working conditions (including the use of community development approaches).

3. Behavioural risk factors (particularly where focused on disadvantaged groups).

4. Healthcare systems (improving access, particularly for marginalized groups).

Most public policies impact on health and can contribute to or reduce inequalities, hence the importance of ‘joined-up government’ – a cross-cutting approach that examines all policies for their impact. As we have seen, income is a major determinant of health status. Improving material conditions for the worst off is therefore an important step towards health improvement.

Traditionally, social democracy has responded to inequality with a simple solution of taking from the rich and giving to the poor. But most governments have pulled back from using redistributive policies that use taxation for fear of alienating the better-off sections of the electorate. Instead, low income has been tackled through increased targeted benefits and the establishment of a minimum wage. The catch-phrase of American democrats is that welfare should offer a hand-up not a hand-out and this is reflected in the emphasis on job creation, education for employability and flexible working.

The Acheson (1998) Report into inequalities in health made 39 policy recommendations, only 3 of which related to the NHS. The report also recommended that priority should be given to improving the health of women of childbearing age, expectant mothers and young children. This reflects a focus in many developed countries struggling with welfare reform to shift redistribution forward in the life-course and concentrate on the young. Attention has also been focused on the working population and the economic case to be made for tackling ill health in a more proactive and integrated fashion. Each year sickness absence and worklessness costs the UK over £100 billion. Mental ill health is a major contributor to the absence of sickness, with over 200,000 people moving onto incapacity benefit due to mental ill health over the last decade (Black 2008). The review ‘Working for a Healthier Tomorrow’ (Black 2008) advocated the establishment of a new integrated, multi-disciplinary ‘Fit for Work’ service to manage ill health at the early stages of absence due to sickness and to encourage staff back to work.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree