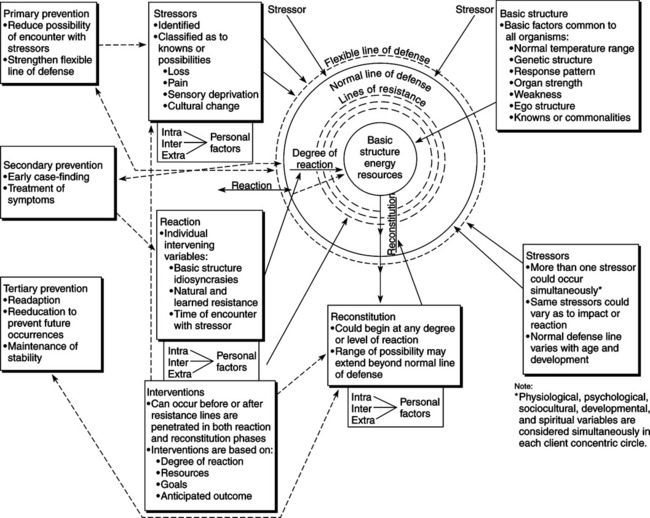

Barbara T. Freese and Theresa G. Lawson Neuman was a pioneer of nursing involvement in mental health. She and Donna Aquilina were the first two nurses to develop the nurse counselor role within community crisis centers in Los Angeles (B. Neuman, personal communication, June 21, 1992). She developed, taught, and refined a community mental health program for post–master’s level nurses at UCLA. She developed and published her first explicit teaching and practice model for mental health consultation in the late 1960s, before the creation of her systems model (Neuman, Deloughery, & Gebbie, 1971). Neuman designed a nursing conceptual model for students at UCLA in 1970 to expand their understanding of client variables beyond the medical model (Neuman & Young, 1972). Neuman first published her model during the early 1970s (Neuman & Young, 1972; Neuman, 1974). The first edition of The Neuman Systems Model: Application to Nursing Education and Practice was published in 1982; further development and revisions of the model are illustrated in the subsequent editions (Neuman, 1989, 1995, 2002b). The Neuman Systems Model is based on general system theory and reflects the nature of living organisms as open systems (von Bertalanffy, 1968) in interaction with each other and with the environment (Neuman, 1982). Within this model, Neuman synthesizes knowedge from several disciplines and incorporates her own philosophical beliefs and clinical nursing expertise, particularly in mental health nursing. The model draws from Gestalt theory (Perls, 1973), which describes homeostasis as the process by which an organism maintains its equilibrium, and consequently its health, under varying conditions. Neuman describes adjustment as the process by which the organism satisfies its needs. Many needs exist, and each may disrupt client balance or stability; therefore, the adjustment process is dynamic and continuous. All life is characterized by this ongoing interplay of balance and imbalance within the organism. When the stabilizing process fails to some degree, or when the organism remains in a state of disharmony for too long, illness may develop. If the organism is unable to compensate through illness, death may result (Neuman & Young, 1972). The model is also derived from the philosophical views of de Chardin and Marx (Neuman, 1982). Marxist philosophy suggests that the properties of parts are determined partly by the larger wholes within dynamically organized systems. With this view, Neuman (1982) confirms that the patterns of the whole influence awareness of the part, which is drawn from de Chardin’s philosophy of the wholeness of life. Neuman used Selye’s definition of stress, which is the nonspecific response of the body to any demand made on it. Stress increases the demand for readjustment. This demand is nonspecific; it requires adaptation to a problem, irrespective of the nature of the problem. Therefore, the essence of stress is the nonspecific demand for activity (Selye, 1974). Stressors are the tension-producing stimuli that result in stress; they may be positive or negative. Neuman adapts the concept of levels of prevention from Caplan’s conceptual model (1964) and relates these prevention levels to nursing. Primary prevention is used to protect the organism before it encounters a harmful stressor. Primary prevention involves reducing the possibility of encountering the stressor or strengthening the client’s normal line of defense to decrease the reaction to the stressor. Secondary and tertiary prevention are used after the client’s encounter with a harmful stressor. Secondary prevention attempts to reduce the effect or possible effect of stressors through early diagnosis and effective treatment of illness symptoms; Neuman describes this as strengthening the internal lines of resistance. Tertiary prevention attempts to reduce the residual stressor effects and return the client to wellness after treatment (Capers, 1996; Neuman, 2002b). Neuman conceptualized the model from sound theories before nursing research was begun on the model. She initially evaluated the utility of the model by submitting a tool to her graduate nursing students at UCLA and published the outcome data in Nursing Research (Neuman & Young, 1972). Subsequent nursing research has produced sound empirical evidence in support of the Neuman Systems Model (Figure 16-1). Neuman (1982) believes that nursing is concerned with the whole person. She views nursing as a “unique profession in that it is concerned with all of the variables affecting an individual’s response to stress” (p. 14). The nurse’s perception influences the care given; therefore, Neuman (1995) states that the perceptual field of the caregiver and the client must be assessed. Neuman presents the concept of person as an open client system in reciprocal interaction with the environment. The client may be an individual, family, group, community, or social issue. The client system is a dynamic composite of interrelationships among physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual factors (Neuman, 2002c, p. 322). Neuman (1995) identifies three relevant environments: (1) internal, (2) external, and (3) created. The internal environment is intrapersonal, with all interaction contained within the client. The external environment is interpersonal or extrapersonal, with all factors arising from outside the client. The created environment is unconsciously developed and is used by the client to support protective coping. It is primarily intrapersonal. The created environment is dynamic in nature and mobilizes all system variables to create an insulating effect that helps the client cope with the threat of environmental stressors by changing the self or the situation. Examples are the use of denial (psychological variable) and life cycle continuation of survival patterns (developmental variable). The created environment perpetually influences and is influenced by changes in the client’s perceived state of wellness (Neuman, 1995, 2002c). Theoretical assertions are the relationships among the essential concepts of a model (Torres, 1986). The Neuman model depicts the nurse as an active participant with the client and as “concerned with all the variables affecting an individual’s response to stressors” (Neuman, 1982, p. 14). The client is in a reciprocal relationship with the environment in that “he interacts with this environment by adjusting himself to it or adjusting it to himself” (Neuman, 1982, p. 14). Neuman links the four essential concepts of person, environment, health, and nursing in her statements regarding primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Earlier publications by Neuman stated basic assumptions that linked essential concepts of the model. These statements have been recognized as propositions and serve to define, describe, and link the concepts of the model. Numerous theoretical assertions have been proposed, tested, and published, as noted throughout Neuman and Fawcett (2002). Neuman used deductive and inductive logic in developing her model. As was previously discussed, Neuman derived her model from other theories and disciplines. The model is also a product of her philosophy and of observations made in teaching mental health nursing and clinical counseling (Fawcett, Carpenito, et al., 1982). Alligood (2006) clarifies that a conceptual model provides a frame of reference, while a grand theory proposes direction or action that is testable. The Neuman Systems Model is both a model and a grand nursing theory. As a model, it provides a conceptual framework for nursing practice, research, and education (Freese, Neuman, & Fawcett, 2002; Louis, Neuman, & Fawcett, 2002; Newman, Neuman, & Fawcett, 2002). As a grand theory, it proposes ways of viewing nursing phenomena and nursing actions that are assumed to be true but may form propositions for testing (Neuman, 2002b). Use of the Neuman Systems Model for nursing practice facilitates goal-directed, unified, wholistic approaches to client care, yet the model is also appropriate for multidisciplinary use to prevent fragmentation of client care. The model delineates a client system and classification of stressors that can be understood and used by all members of the healthcare team (Mirenda, 1986). Guidelines have been published for use of the model in clinical nursing practice (Freese, et al., 2002) and for the administration of healthcare services (Shambaugh, Neuman, & Fawcett, 2002). Several instruments have been published to facilitate use of the model. These instruments include an assessment and intervention tool to assist nurses in collecting and synthesizing client data, a format for prevention as intervention, and a format for application of the nursing process within the framework of the Neuman Systems Model (Neuman, 2002a; Russell, 2002). Neuman (2002a) outlines her nursing process format clarifying the steps of the process for use of her model in Appendix C (Neuman & Fawcett, 2002, pp. 348-349). Russell (2002) provides a review of clinical tools using the model to guide nursing practice with individuals, families, communities, and organizations. The breadth of the Neuman model has resulted in its application and adaptation in a variety of nursing practice settings, including hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, hospices, mental health units, childbirth centers, and community-based services such as congregational nurse practices. Numerous examples are cited in Neuman’s books (1982, 1989, 1995, 2002b). The model’s wholistic approach makes it particularly applicable for clients who are experiencing complex stressors that affect multiple client variables such as end-stage kidney disease (Graham, 2006). The model is used to guide nursing practice in countries throughout the world. As an example, it is used in Holland to guide Emergis, a comprehensive program of mental health that provides psychiatric care for children, adolescents, adults, and elderly, and addiction care and social services (Munck & Merks, 2002). This model has been modified for nursing practice in Malaysia by strengthening the role of the family in caring for patients (Shamsudin, 2002). Neuman’s model provides a systems perspective for use with individuals and families, for community-based practice with groups, and in public health nursing, as its wholistic principles can assist nurses to achieve high-quality care through evidence-based practices (Ume-Nwagbo, Dewan, & Lowry, 2006). Anderson, McFarland, and Helton (1986) used the model for a community health needs assessment in which they identified violence toward women as a major community health concern. This model has been used to promote health for senior citizens at a community nursing center in Pennsylvania (Newman, 2005), to guide a public school nurse clinical practice (Vito, 2005), and as the framework for a parish nurse practice (Kathleen Vito, personal communication, April 21, 2005). Likewise, the model is functional in the acute care setting. For example, the Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit adopted the Neuman Systems Model as the nursing conceptual model to be implemented at their institution. As part of the implementation process, various documents were revised or created to reflect nursing care using concepts of the model, such as the Pediatric Admission Database and the Neuman Process Summary (Torakis & Smigielski, 2000). It is used to guide nursing practice in the Foote Health System in Michigan (Johnson-Crisanti et al., 2005). The Neuman Systems Model is used effectively to enhance advanced practice nursing (Fawcett, Newman, & McAllister, 2004; Geib, 2006; Gigliotti, 2002). For example, clinical nurse specialists have used the model to identify major health concerns for elderly adults living in the community (Imamura, 2002). The model has also been used to direct the development of guidelines for a community-based Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner program (Melton, Secrest, Chien, & Andersen, 2001). The model works well for multidisciplinary use. As an example, it is used to guide a team approach to holistic care for older adults after hip fracture (Kain, 2000). It also has proved useful in hospital-based case management in several Kansas hospitals, with the development of case management teams involving social workers and nursing staff (Wetta-Hall, Berry, Ablah, Gillispie, & Stepp-Cornelius, 2004). Further research continues to validate its applicability beyond nursing. The model is well accepted in academe and is used widely as a curriculum guide. It has been used throughout the United States and in other countries, including Australia, Canada, Denmark, England, Holland, Japan, Korea, Kuwait, Portugal, and Taiwan (Beckman et al., 1994; Lowry, 2002). In an integrative review of use of the model in educational programs at all levels, Lowry (2002) reports that “although the trend is toward eclecticism in nursing education today, the Neuman Systems Model has served many programs well…” and frequently is selected in other countries to facilitate student learning (p. 231). Guidelines have been published for use of the model in education for the health professions (Newman et al., 2002). The model’s wholistic perspective provides an effective framework for nursing education at all levels. Lowry and Newsome (1995) reported on a study of 12 associate degree programs that use the model as a conceptual framework for curriculum development. Results indicate that graduates use the model most often in the roles of teacher and care provider, and that they tend to continue practice from a Neuman Systems Model–based perspective following graduation. Neuman’s model has been selected for baccalaureate programs on the basis of its theoretical and comprehensive perspectives for a wholistic curriculum, and because of its potential for use with individuals, families, small groups, and the community. Neumann College Division of Nursing was the first school to select the Neuman Systems Model as its conceptual base for its curriculum and approach to client care in 1976. The model has been used at Lander University in Greenwood, South Carolina, as the framework for baccalaureate nursing education since 1987 (Freese & Lander University Nursing Faculty, 1995). This model provides the framework for nursing education programs at Palm Beach Atlantic University (Alligood, 2004), East Tennessee State University (Lois Lowry, personal communication, April 22, 2005), Purdue University at Fort Wayne (Boxley-Harges, Beckman, & Bruick-Sorge, 2007), and Newberry College (Betsy McDowell, personal communication, January 3, 2007). The model works equally well to guide clinical learning. For example, it is used with nursing students at a community nursing center (Newman, 2005), and to teach nursing students to promote the health of communities (Falk-Rafael et al., 2004). It is used as a comprehensive framework to organize data collected from maternity patients by undergraduate nursing students at the University of South Florida (Lowry, 2002). Bruick-Sorge (2007) reported using the model in the clinical simulation setting to improve critical thinking skills by using model concepts. The model’s effectiveness as a framework for patient education has been demonstrated. Salvador (2006) reported its use by a group of nurses to develop an oral care guide for patients who have autologous stem cell transplantation. The model’s inclusion of both client perception and nurse perception makes it particularly relevant for teaching across cultures. Neuman (2001) stated that several faculty experts are facilitating use of the model in diverse cultures in countries that include Guatemala, Kuwait, Thailand, and Taiwan, and it is used to guide nursing curricula in Jordan, Taiwan, Guam, and Iceland. A significant amount of research has been conducted over the past decade on the components of the model to generate nursing theory and using the model as a conceptual framework to advance nursing as a scientific discipline. Rules for Neuman Systems Model–Based Nursing Research as specified by Fawcett, a Neuman model trustee, are based on the content of the model and related literature (Fawcett & Gigliotti, 2001). Other guidelines have been published to guide use of the model for nursing research (Louis et al., 2002). In the third edition of The Neuman Systems Model, Louis (1995) discussed its use in nursing research and identified nearly 100 studies, conducted between 1989 and 1993, for which the model provided the organizing framework. The third edition also contains an annotated bibliography of selected studies conducted from 1989 to 1993, with an appendix listing research studies published in journals, dissertations, and master’s theses. In the fourth edition of The Neuman Systems Model, Fawcett and Giangrande (2002) present an integrated review of 200 research reports of model use that were published through 1997. Skalski, DiGerolamo, and Gigliotti (2006) reported a literature review of 87 Neuman Systems Model–based studies to identify and categorize client system stressors. The Neuman Systems Model is used frequently by nurse researchers as a conceptual framework, as it lends itself to both quantitative and qualitative methods. Recent examples of qualitative studies include studies of raising consciousness in critical care nurses (Moola, 2006), of decision making in asynchronous online education (Molinari, 2001), of the effects of chronic arthritis (Potter & Zauszniewski, 2000), and of the meaning of spirituality among aging adults (Lowry, 2005). Examples of quantitative studies include investigations of problems experienced by infants exposed to tobacco smoke in the environment (Stepans & Knight, 2002; Stepans, Wilhelm, & Dolence, 2006), of coping behaviors of women with family history of breast cancer (Lancaster, 2005), of maternal-student role stress (Gigliotti, 2004, 2007), of physical activity and health-related quality of life in the elderly (Binhosen et al., 2003), of elder abuse (Kottwitz & Bowling, 2003), and of needs of cancer survivors (Narsavage & Romeo, 2003). Jones-Cannon and Davis (2005) implemented a mixed method to examine coping strategies among African American women who care for their aging parents. This model works well for studying areas of interest across cultures. It was used recently in Malaysia to study patients’ spiritual needs and the role of nurses in meeting them (Shamsudin, 2002), to study physical activity and health among elderly persons in Thailand (Binhosen et al., 2003), to compare child health risk factors in Korea and the United States (McDowell, Chang, & Choi, 2003), and to study the effectiveness of a community-based pulmonary rehabilitation program for Thai individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Noonhill, Sindhu, Hanucharunkul, & Suwonnaroop, 2007). Graduate students frequently use the model for dissertations and theses. Recent examples include studies on the relationship among stress, role and job strain, and sleep in middle-aged nurse shift workers (Brown, 2004), on the childhood experiences of women who experience intimate partner violence (Reeves, 2005a, 2005b), on the created environment as a coping strength for homeless abused women (Hemphill, 2006), on the relationship between comfort, spirituality, and quality of life among residents of a long-term care facility in Taiwan (Lee, 2005), and on the relationship between alcohol use and unintentional death in older adults (Rohr, 2006). The Biennial Neuman Systems Model Symposium provides a rich forum for presentation of research (completed and in progress). At the tenth (2005) and eleventh (2007) symposia, nurses from the United States, Canada, and Holland reported on numerous studies that used the model. Studies were reported on the experiences of women related to intimate partner violence (Reeves, 2005b), on perceived health status changes in criminally victimized older adults (Burnett, 2005), on the influence of each variable on perceived health in older adults (Buck, 2005), and on Asian American child-rearing beliefs and practices (McDowell, 2005). Research presented at the eleventh symposium included studies on the lived experience of the chemically dependent nurse (Dittman, 2007), faculty development prior to facilitating online coursework (Greer & Clay, 2007), interventions to reduce nurse burnout (Gunesen, 2007), the discovered strengths of homeless abused women (Hemphill & Quillen, 2007), sleep quality in cardiothoracic surgery patients (Nelson, 2007), and Chinese parent’ understanding of child vehicle restraints (Ren, Snowdon, & Thrasher, 2007).

Systems Model

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

Nursing

Person

Environment

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

LOGICAL FORM

APPLICATIONS BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

Education

Research

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access