Introduction

The previous three chapters have explored and critiqued how different teamwork interventions may be designed and implemented, informed by theory and evaluated. In this chapter we build on these discussions by presenting a synthesis of three studies of interprofessional teamwork which we have undertaken during the past 15 years. The studies were based in three countries: South Africa, the UK and Canada. Our aim in presenting this synthesis is to provide an insight into how we designed and evaluated a number of different interprofessional interventions and also discuss our experiences related to this work.

Initially we provide the contextual information related to each of the studies before presenting details on the methodological process related to how we analysed and synthesised these data sets. Findings from this synthesis are then presented in terms of the main themes from across the three studies; the aim is to offer an in-depth empirical account of how interprofessional collaboration and teamwork operate in these different clinical contexts. Lastly, we discuss the broader implications of this work in relation to other settings.

The contextual information is presented below, including the local clinical and institutional settings of the studies. This provides a frame for understanding local processes and findings particularly in respect to how each site evolved from design to implementation and evaluation.

Study 1: South Africa

This study emerged from early clinical audit work on general medicine wards based in a large teaching hospital in Cape Town, which suggested that professionals worked in a routinised manner and were not responsive to individual patient needs. As a result, senior clinicians collaborated with researchers and clinical managers to develop LOCIS (Level of Care Intervention Study) – an intervention which aimed to tailor the level of care provided to each patient according to need. This tailoring required an improvement in interprofessional communication among all ward staff, especially between nursing and medicine staff. The intervention aimed at improving interprofessional relationships and also the delivery of care.

LOCIS included four elements. First, team-building activities designed to improve interprofessional relations were provided to ward staff in order to clarify each profession’s contribution, responsibilities and frustrations. These teambuilding activities also aimed to promote agreement on shared patient care values and goals, and to ensure that staff would meet as named individuals rather than as members of separate professions. Second, a reorganisation of staff occurred in which nursing and medical staff were split into two teams, each consisting of one senior physician, a number of junior physicians and nurses in order to provide better targeted and more responsive care. Third, nursing staff were mandated by their clinical leaders to eliminate task-oriented nursing (which focused on task completion rather than being responsive to patient needs) and to share knowledge and patient responsibility among all members of the nursing team. Fourth, each medical-nursing team was mandated by their clinical leaders to conduct a daily joint planning ward round, during which care plans were reviewed for each patient and signed by both nurse and physician.

LOCIS employed a controlled-before-and-after design to evaluate its processes and impact. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected in the form of patient care processes, outcome and satisfaction measures, staff surveys, observations and interviews with a range of junior and senior clinical staff.

For further information about this study, see Zwarenstein et al. (2003).

Study 2: The UK

Based in a large teaching hospital in London, this study was undertaken in a medical directorate consisting of five general medical wards and one emergency admissions ward. An intervention was designed to respond to concerns within the medical directorate that the distribution of medical teams (including senior and junior physicians) and their patients across a large number of medical wards had a range of negative effects including:

- Lengthy ward rounds

- Difficulties for medical teams in getting to know ward-based teams, which included nurses, therapists, social workers and pharmacists. This, it was thought, resulted in less involvement by ward-based staff (e.g. nurses, therapists) in decision-making on patient care

- Inefficiencies due to medical staff having to move between wards

- Patients not always receiving optimal care if they were admitted, within the rota system, to a physician from a speciality different to that of their initial presenting condition.

To address these concerns, a ward-based medical team (WBMT) system was developed and introduced by the directorate leaders and clinicians. This system aimed to promote effective collaboration by basing each medical team and the patients for whom they were caring on one ‘home’ ward, rather than across multiple wards. A new triage system was also introduced to ensure that patients were managed by the appropriate specialists. As part of this, a list of health conditions was identified that would require the transfer of the patient to a medical team focusing on a particular speciality.

The study aimed to explore the impact of the WBMT system on interprofessional collaboration and on the clinical service delivered to patients. A mixed methods research design was used to develop a comprehensive understanding of the effects of the new system. Questionnaire, audit, observational, interview and documentary data were collected with practitioners, managers and patients before introduction of the WBMT system and also 1 month and then 9 months after its introduction.

For further information about this study, see Reeves and Lewin et al. (2003) and Reeves and Lewin (2004).

Study 3: Canada

The SCRIPT (Structuring Communication Relationships for Interprofessional Teamwork) programme was a multi-year project. It had one broad aim – to work with staff to introduce interprofessional education and collaboration within a number of local medical, primary and rehabilitation care teaching units and practice settings. To achieve this aim, the project had three key objectives: to design empirically based interventions to foster interprofessional collaboration and teamwork; to pilot-test interventions; and, if successful, to implement these across the three selected clinical contexts. A multi-method study was designed by a team of researchers and clinicians to explore factors that facilitated or impeded interprofessional communication across these clinical contexts in Toronto.

Within the general medicine arm of this study, a series of observations and interviews were undertaken to understand the nature of interprofessional teamwork within this setting. As a result, researchers developed the following four-step communication intervention designed to be employed by professionals in their faceto-face interprofessional collaboration:

1. Introduce oneself to the member(s) of the other profession by name

2. State to the other individual(s) one’s own professional role in the team and describe it with respect to the patient under discussion

3. Share with the other professional their unique, profession-specific issues, problems or plans relating to the patient

4. Elicit feedback from the other professional by using prompts such as ‘Do you have any concerns?’ or ‘Is there something else I should consider?’

These four steps were based upon the following two assumptions: first, if professionals continuously introduced themselves by name and role, any confusion or anonymity would be reduced. Second, if professionals shared their perspective and elicited a collegial point of view, opportunities to solve a patient care problem would be enhanced. Strauss’s (1978) theory of negotiated order underpinned the design of the intervention (see Chapter 5). Evaluation of SCRIPT was planned as a randomised control trials (RCT) with an in-depth process evaluation across five hospitals, involving 20 general medicine units.

For more information about this study, see Zwarenstein et al. (2007), Miller et al. (2008), Gotlib Conn et al. (2009) and Reeves et al. (2009c).

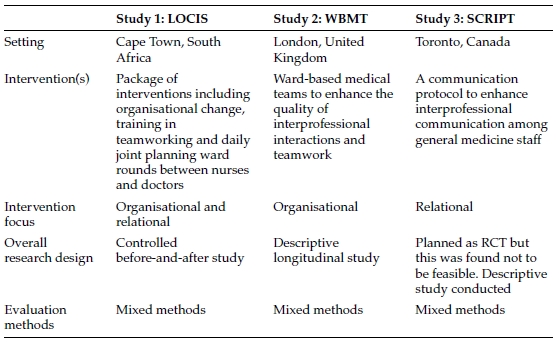

Table 8.1 provides an overview of information from these three interprofessional cases.

Applying our interprofessional typology of in Chapter 3, these three studies can be seen as examples of ‘teamwork’ within a continuum of other forms of interprofessional work (see Figure 3.1). However, we would see their place as near to the boundary with ‘collaboration’. This is because the interactions we described below contains both elements of teamwork (including shared responsibility for decisions and activities, interdependence and team tasks which were often complex) and some elements of collaboration (in that team tasks were fairly predictable and not very urgent and a shared identity was not a strong feature of these teams). Without claiming that they were exemplars of teamworking, these studies do provide a rich data set for understanding issues related to the nature of interprofessional relations in acute general medicine settings. Such settings are the site for a large proportion of interprofessional care delivered within health systems across a range of jurisdictions.

While all three studies gathered both quantitative and qualitative data, this chapter reports a synthesis of the following qualitative data:

- Over 200 hours of observations and 30 interviews with a range of different junior and senior health care professionals (South Africa)

- 90 hours of observations and 74 interviews with a range of different junior and senior health care professionals (UK)

- 155 hours of observations, 53 interviews with a range of different junior and senior health care professionals, and 5 hours of work-shadowing data from a range of ward-based professionals (Canada).

We focus on the qualitative data sets – the observations in particular – as they provide a rich detailed account of the nature of interprofessional relations ‘in action’. As we noted in Chapter 6, the current teamwork literature tends to rely on individuals’ perceptions of teamwork which can only provide a normative account of team relations, not an actual insight into the realities of teamwork.

The following process was undertaken to analyse and synthesise materials for this chapter. Drawing on elements of the meta-ethnographic approach (Noblit and Hare, 1988), which aims to translate ideas and concepts across different studies, we first read and re-read each of the reports generated from the three studies, noting their key themes and any explanations offered. Second, we abstracted information from each study on its aims, settings, theoretical background, sampling, data collection and data-analysis approaches, findings in the form of key themes and any recommendations offered on interprofessional working. For each study, abstraction was completed by one of us who had not been involved in the study and then discussed with the others. Third, we compared and contrasted the key themes to identify related concepts, which in turn were the basis for the synthesis we present below.

We now offer key themes from our synthesis. We initially outline the nature of interprofessional teamwork in the study settings prior to the implementation of the interventions. We then go on to outline how the interventions affected (or failed to affect) the nature of interprofessional relations across these settings. Table 8.2 provides an overview of key findings.

Table 8.2 Main findings from the three studies.

| Study 1: LOCIS – South Africa | Study 2: WBMT – The UK | Study 3: SCRIPT – Canada |

| Key findings – pre-intervention | ||

| Most IP interactions were terse and serendipitous. Those involving physicians were medically led and were in the form of ‘orders’. | Typically, IP interactions were brief and serendipitous. Those involving physicians were generally medically led and were in the form of ‘requests’. | In general, IP interactions were terse and serendipitous. Those involving physicians were medically led using ‘orders’. |

| Intraprofessional and IP interactions (involving nurses, therapists and pharmacists) were lengthier and friendlier. | Physician–nurse relations slightly more cordial than the other two sites. | Intraprofessional and IP interactions lengthier and friendlier. |

| Weekly team meetings physician-dominated. | Intraprofessional and other IP interactions were lengthier and generally friendly. Weekly team meetings provided a regular forum for communication. Poor attendance of physicians and nurses (due to competing commitments) often undermined their value. | Daily team meetings had cordial interactions, though provided limited IP communication. |

| Key findings – post-intervention | ||

| Improved IP working with professionals more aware of communication. | Physicians’ interactions with other professionals were more regular. Consequently, nurses and other staff felt there was a better IP rapport. | IP interactions and nature of relations remained largely unchanged. |

| Physician–nurse interactions seen to have become less hierarchical. | IP interactions remained terse.Weekly IP team meetings remained poorly attended by physicians and nurses. | |

| Physicians displayed a greater awareness of the constraints on nurses’ time. |

Note: IP = interprofessional.

Interprofessional interactions before intervention

General nature of interprofessional interactions

In general, the wards across all settings were very busy. At any one time, a number of people, including relatives and friends of the patients as well as staff from other units within the hospital, could be entering or leaving. Staff were also consulting with patients, undertaking ward rounds and minor procedures, completing paperwork, dealing with telephonic and verbal enquiries from other professionals, patients and relatives, arranging interventions for patients, cleaning the ward and making beds, serving food and drink, as well as attending to the care needs of patients. The following extract, taken from the UK study, indicates the nature of this setting:

A senior physician comes into the ward and asks who is in charge. A junior nurse says, ‘I am’. ‘Oh’, he replies, ‘I would like to speak to a staff nurse’. He then talks to one of the staff nurses about the transport required by a patient who is going for a procedure outside of the hospital. […] A junior physician comes into the ward and goes to the bedside of one of the patients. She then goes to fetch some syringes and goes back to the bedside to take blood specimens. She checks the specimens, tells a staff nurse that they can ‘go up’ [to the laboratory] and goes back into the patient bay. A few minutes later another junior physician comes into the ward, goes to the nurse’ station and asks for urgent bloods to be collected. He then hangs about waiting for a call that will let him know where his ward round is. He then leaves the ward. At the same time, one of the staff nurses is trying to help a person who is looking for a relative who was moved from the admissions ward to another part of the hospital. A dietician comes to the nurses’ station and asks this nurse some questions about a patient’s eating. She makes a note in the folder and chats to the nurse about future care with regard to eating. (Observational data, UK)

Findings from observational data gathered in the Canadian and South African settings provided very similar insights regarding the nature of interprofessional interactions in these settings. Indeed, our observations indicated that interprofessional interactions, especially those involving physicians, across the three sites were generally short, largely unstructured and often serendipitous. If a professional had a query, they would usually look around the ward for another professional who might be able to answer it. If the appropriate professional was found, the two might have a brief discussion and then continue with their other tasks.

Interactions between physicians and other professionals on the wards

Across the three sites, we found that interprofessional interactions which involved physicians and other health and social care professionals (e.g. nurses, therapists and social workers) were particularly terse, as illustrated in the following extracts:

The sister [senior nurse] asked the intern [junior physician] when they were going to do the rounds and he answered that he was waiting for the registrar […], noting that ‘we will call you’. (Observational data, South Africa)

An intern comes in and grabs three charts from the cart. He asks the social worker if any forms need to be filled out for a patient then leaves. (Observational data, Canada)

In general, interprofessional interactions appeared to be anonymous – few staff knew the names or roles and scopes of practice of their colleagues. Across the three sites, the data indicated that a significant proportion of interactions involving physicians were unidirectional rather than taking the form of a discussion. Typically, such interactions were from physician to nurse, as illustrated below:

A house officer [junior physician] asks the charge nurse, who is busy with the task of wheeling a commode through the ward, for a dynamap machine. She tells him to ask the nurse on the other side of the ward. (Observational data, UK)

In the UK, these interactions were focused largely on providing medical ‘requests’ for the progression of care. This was also the case in Canada and South Africa, where this type of interaction was termed medical ‘orders’, perhaps reflecting the character of these interactions. Furthermore, nurses and therapists and other professionals offered input primarily when prompted by physicians. For example, while many physicians in the South African study perceived their communication with registered nurses to be satisfactory, their comments suggested that this view was based on nurses accepting their orders:

Communication with the sisters is good. We all have responsibilities for the patients. As long as they carry out their orders I don’t have a problem. (Physician interview, South Africa)

We talk when we need to. I have no complaints. (Physician interview, South Africa)

In the UK, we found that nurses’ communication with physicians was focused almost entirely on obtaining a medical response to questions they had about care. While physicians in the UK study were fairly responsive to these questions, those in Canada and South Africa often ignored nurses’ questions or comments, or referred the nurses back to the original order or instruction that had been given. While not close, relations between physicians and nurses in the UK setting appeared slightly more cordial than in the other two settings.

In addition, across the sites, ward-based interactions between physicians and other professionals largely involved junior physicians. Indeed, there was a noticeable absence of senior physicians from the wards for most of the working day. As a result, most day-to-day interprofessional activities and decisions regarding patient care were taken by their juniors (registrars, residents, interns, house officers).

Interactions among professionals other than physicians on the wards

By contrast, data from the three study sites indicated far more interprofessional communication among professionals other than physicians on the wards. Interactions that involved nurses, therapists, pharmacists and social workers were generally friendlier and less rushed, as the following extracts indicate:

The speech language pathologist and dietician are still talking. The speech language pathologist feels stressed […] ‘I need a psych consult,’ she jokes. (Observational data, Canada)

A nurse and a physiotherapist have a discussion about a patient – the physiotherapist explains problems she is having with a patient […] the exchange lasts for a good ten minutes. I am struck by the depth and length of this discussion. (Observational data, UK)

As the extracts above indicate, these types of interactions often involved discussion of care issues and exchanges of a humorous nature.

Interprofessional meetings

Interprofessional meetings were held in all three settings with a range of purposes. In the Canadian setting, interprofessional rounds were held everyday. While interactions during these rounds were friendlier than on the wards, interprofessional discussion was still limited. In both the UK and Canada, nurses reported refraining from participating in or interrupting interprofessional meetings. This was in part because they found these meetings were of limited use to their work. Also, nurses sometimes felt intimidated by senior physicians or felt that their views were not valued. Nurses and other professionals therefore felt that their opinions went largely unvoiced during these meetings.

Physicians in these two settings often complained that interprofessional meetings were of little use and saw the main beneficiaries as being occupational therapists, physiotherapists and social workers:

From the medical perspective, the information that is shared at [our interprofessional meetings] is not always useful, like what the functional ability of a patient is. (Physician interview, Canada)

In the UK, physicians and, to a lesser extent, nurses saw ward rounds as an important forum for interprofessional communication. In practice, though, they were generally a uniprofessional medical activity. Even if other professionals attended ward rounds, they tended to be on the periphery and therefore not involved in any of the clinical decision-making that occurred.

One regular mechanism for interprofessional communication and information exchange in the UK setting was the weekly interprofessional meeting. These gatherings were intended to allow physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers and care coordinators working with each medical team to update one another, discuss the progress and problems with patient care and plan patient discharges. Some professionals considered these meetings a key mechanism for interprofessional interaction:

Those [interprofessional] meetings are really important. That’s when we find out […] the nitty gritty of what is actually wrong with them [patients]. (Social worker interview, UK)

However, both physicians and nurses regularly failed to attend interprofessional meetings, which often delayed decisions on patient care and discharge. Nurses cited heavy workloads combined with a shortage of staff as the reasons for their non-attendance. For the physicians, especially the senior ones, the nature of their duties meant that they were often working in other parts of the hospital or undertaking ward rounds or clinics during the time scheduled for these meetings.

In the South African setting, interprofessional meetings to discuss the social circumstances of patients were usually controlled by registrars and medical interns who often ignored differing views from other staff. Most information was provided by interns while registrars almost always gave orders regarding when patients had to be seen by a social worker or specialist nurse. The ward nurses seldom said or were asked anything.

Spatial factors

A mechanism employed by staff in both Canada and the UK to overcome interprofessional communication difficulties was the use of the hospital corridors for informal information exchange:

We catch up on the corridor […] informally speak to physios and OTs and social workers, so there is good group contact there. (Physician interview, UK)

While most patients in the UK site were in multi-bed wards, patients in the Canadian setting generally had private rooms. This decreased the likelihood of opportunistic interprofessional interaction at the bedside and increased the importance of hospital corridors for communication. By contrast, the use of such informal mechanisms was not reported to be used by the professionals in the South African study.

Uniprofessional relations

Across the three sites, uniprofessional interactions were richer than interprofessional discussions and included both work and social elements. In the Canadian setting, many professionals saw interprofessional rounds as a low priority and uniprofessional activities as more important. This was particularly so for physicians. As noted above, there were also more social interactions within professional groups than between them:

A resident jokes that they will be answering pages only before the [hockey] game starts. Another resident explains that they will be watching [medical drama]. A third resident tells her it is a repeat, and when she asks which episode, two residents teasingly respond that, ‘it’s the one where someone gets an IV and is intubated, and then something else happens and then someone sleeps with someone.’ There is a lot of laughter. (Observational data, Canada)

Many of the physicians in the UK setting saw collaboration as an activity involving different medical teams or specialities rather than other professional groups. For example, observations revealed significant discussion at management meetings in the clinical directorate on ways of improving collaboration between medical teams and with other medical specialties. By contrast, ways of improving interprofessional collaboration received far less attention.

Interprofessional interactions after intervention

Following the implementation of the respective interventions, in all three settings, nurse-physician relations remained central to interprofessional collaboration. In both Canada and the UK, the nature of communication between physicians and other professionals did not change significantly following the interventions – it remained terse, task-oriented and seldom included any social content:

The charge nurse asks a passing physician, ‘are you looking after patient X?’ The physician says, ‘no, X is’. The charge nurse then asks, ‘What’s his bleep [page] number?’ The physician gives it and goes on. (Observational data, UK)

Although in the UK, due to the formation of WBMTs, interprofessional communication between the physicians and other professionals did become more frequent. By contrast, there appeared to be more interprofessional collaboration in the South African setting following the intervention. Through working together more closely on the ward level, professionals appeared to have become more aware of the need for better communication and saw this aspect of their work as having improved:

The teams now involve everybody, doctors, colleagues, as well as pupil and student nurses. Even the domestics [domestic workers or cleaners]. Now I experience them as all behaving as part of a team. Five months ago it was not like that, but now I can see the difference. They are suddenly talking to each other. (Auxiliary staff, interview, South Africa)

There were a number of aspects to this change in interactions in South Africa communication between physicians and nurses was seen to have become less hierarchical at ward level, medical staff displayed a greater awareness of the constraints on nurses’ time, and both nurses and physicians described having a better understanding of each others’ roles and those of their colleagues on the wards:

This kind of understanding between nursing and medicine is improved by working in a specific team. I would feel free to tell Doctor A what I think. (Nurse interview, South Africa)

In South Africa, as a result of the intervention, both nurses and physicians also reported improved communication with patients during ward rounds and more generally:

We are more involved with our patients than before. I spend more time talking to them, finding out about their domestic situation to enable me to plan discharge and I tend to give more information to them than in the past. (Nurse interview, South Africa)

In the UK, interviews with patients and professionals suggested that patients had somewhat better access to staff following the intervention, although they still encountered difficulty at times. The Canadian study did not include a patient perspective.

Across all three settings, following the implementation of the interventions, professionals continued to place very little ‘social capital’ (Bourdieu, 1986) on the use of communication as a mechanism for improving interprofessional relations and/or the delivery of care. Instead, they continued use communication for the completion of their profession-specific tasks. Physicians in particular, often did not see any benefit to this communication and, consequently, it became invisible to them. For example, physicians in the Canadian study described interprofessional meetings as a largely ‘redundant’ part of their work. In both the UK and Canada, there were numerous examples of physicians continuing to ignore or not respond to other professionals when working on the wards:

Two senior-looking physicians come into the ward. One starts using the computer at the nurses’ station – almost pushing a health care assistant out of the way – while the other reads a newspaper that is lying on the desk in the nurses’ station. They don’t speak to the health care assistant who is sitting at the nurses’ station, but talk to each other about some problem with the computer. (Observational data, UK)

Linked to this, there continued to be very little social communication on these wards. This may be because these professionals saw no value in maintaining communication, whose only perceived value is social, despite the importance of such forms of interaction in maintaining relations with other professionals.

As indicated above, only two of the interventions (South Africa and the UK) resulted in marginal gains for interprofessional teamwork. While the South Africa study reported most improvements, with increases in the frequency and quality of interactions with physicians (though no change in the underlying nature of relations); data from the Canadian study indicated that the intervention had no detectable effect. The longevity of these interventions was also limited. For example, in South Africa, despite some changes in nurse-physician relations, senior management decided not to undertake any further implementation across the hospital. Similarly, in the UK setting, despite some gains, the intervention was not implemented any further. In addition, attempts to obtain funding at this site to expand the intervention to include a team-building element were unsuccessful. In Canada, due to limited physician support and the absence of a local champion, following completion of a pilot-testing phase there was no further intervention activity. Plans for a multi-hospital RCT therefore became unfeasible.

The three studies reported in this chapter are accounts of teamwork ‘in action’, based on detailed qualitative analysis of a substantial body of ethnographic observations of interprofessional teamwork and collaboration. As noted above, while most analyses draw on individuals’ perceptions of teamwork, and are therefore often normative in nature, these data provide rare empirical insights into how teamwork is undertaken in practice. For example, this approach has helped to highlight the use of informal modes of communication, such as corridor conversations, alongside more formal teamworking activities, such as interprofessional meetings.

The data are also unusual in that they are drawn from a similar level of the health system (general medicine wards within large, tertiary referral hospitals based in urban locations) but from very different socio-economic and political settings (Canada, South Africa and the UK). Important differences between the settings include the level of autonomy of physicians, which due to remuneration arrangements is higher in Canada compared to the other two sites, and demographic characteristics of patients, with most patients in the South African study being black and of low socio-economic status; those in the UK setting being very ethnically diverse but generally of low socio-economic status; and those in Canada being largely elderly and of higher socio-economic status.

Juxtaposition of these three cases is useful in highlighting both aspects of teamworking that seem to be consistent across country settings (e.g. terse interactions) as well as elements that differ (e.g. contrasting local contexts), thereby helping to tease out the ‘core’ features of teamworking in acute medicine settings. Importantly, differences across the study settings in the socio-economic status of patients did not seem to have an impact on the nature of interprofessional collaboration.

While not included here, data on patient perspectives from South Africa and the UK were useful in understanding the impacts of the interventions on patient experiences of care (e.g. Reeves and Lewin et al., 2003). For example, patients and their families in the UK reported having better access to physicians following implementation of the WBMT intervention, which made it easier for them to obtain information and plan for care following discharge. (As noted above, the Canadian study did not include a patient perspective).

The interventions in both South Africa and the UK did not explicitly draw upon theory in their development – both were designed in a pragmatic manner to help resolve identified difficulties in the provision of care within these settings. By contrast, the SCRIPT intervention drew on Strauss’s (1978) negotiated order perspective to design the four-step communication activity, which helped developed an approach which was sensitive to the nature and role of negotiation within a general medicine context.

Factors affecting the uptake of the interventions in the different settings

As we discussed above, the uptake of the interventions, and their consequent impacts on interprofessional teamworking was stronger in the South African and UK cases, compared to the Canadian case. Box 8.1 outlines three factors which affected the uptake of the interventions in these different settings.

As Box 8.1 indicates, the general absence of interprofessional champions, wider professional/organisational support and role modelling can diminish the impact of the interprofessional teamwork interventions. Furthermore, differences between physician autonomy and status within Canada compared with the other two settings added an additional factor which compounded the others and impeded any improvement in teamwork associated with this intervention.

Box 8.1 Factors which limited the effects of teamwork interventions.

Local champions. There was both buy-in and championing of the intervention by key senior staff in South Africa and the UK, particularly by lead physicians. This was not the case in the Canadian setting. As a consequence of the work of local champions, senior-level physicians and nurses in the participating facilities in South Africa and the UK either gave instructions to their junior staff, or achieved their support for the changes entailed by the intervention. Furthermore, organisational changes needed to support the intervention were made by senior levels of management.

Ward-level role modelling. In all three settings, there was a general absence of senior physicians from the wards for most of the working day. Most day-to-day decisions regarding patient care were taken by registrars (residents), particularly in Canada and the UK. Consequently, there were few opportunities for senior physicians to ‘role model’ more effective forms of teamworking to their junior staff.

Autonomy and status of physicians. In both the UK and South Africa, physicians work within publicly funded hospitals, and appear to have lower levels of autonomy than in Canada. This appears to be linked to the fact that, in Canada, physicians are effectively self-employed, while in South Africa and the UK they are salaried employees. As a result, physicians in these two settings appeared to have a greater attachment and commitment to building effective teams.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree