Chapter 5 Symptom patterns

A truly holistic and integrated medical approach is achieved by using a common framework and language for the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of health and disease, and by using this same framework to describe everything in nature. Traditional medical systems use consistent terms to describe the qualities and characteristics of seasons, nature, food, herbs, times of day, stages of life, body composition and temperaments, and to describe symptoms and diseases. This consistency in terminology aids greatly in understanding and assessing the relationship between human beings and their environment and lifestyle.

External/Internal

Externally focused patients are preoccupied with outside factors – what they do for a living, how many children they have, their job, and their responsibility to others. Those that are externally focused become concerned with their health when it affects their inability to fulfill their responsibilities to others. Predominantly, externally focused patients have less awareness of their psychological, functional, or structural state; for example, the frequency of bowel movements, the cause of bruises, the presence of muscle tension, even their own thoughts, or what they recently ate. They are less aware of the timing, intensity, and duration of physical symptoms or how these symptoms relate to their lifestyle.

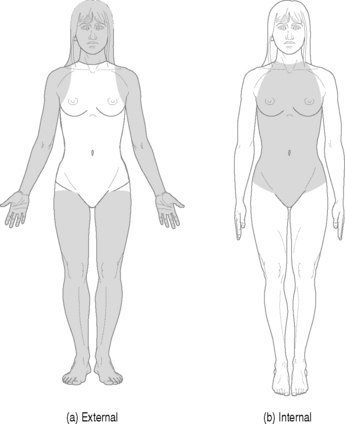

Internal and external intentions look at a person’s psychological state and recognize that these states are mirrored in the physical body (Fig. 5.1). The closer the symptom is to the midline or medial aspect of the body part the more it is about ‘self’. The more symptoms are lateral, or on the periphery the more they are about a patient’s reaction to something external or someone else. For example, Fig. 5.2 indicates an external stance and Fig. 5.3 an internal sitting posture.

Fig 5.1 Internal/external. (a) External. The focus of a person’s energy and attention is on external events and situations. Symptoms most commonly appear on the periphery and lateral aspects of the body. (b) Internal. The focus of a person’s attention is on the self and how situations impact them personally. Symptoms most commonly appear in medial and central aspects of the body.

Symptoms that manifest on the face tend to be associated with external factors or when a patient is concerned with how they are perceived by others, as the face is the aspect of the body that is the most visible to the outside world. With symptoms there often is a blending of both. The extremities, for example, tend to represent our relationship to the external world. The arms are used to give and receive; with the legs we move forward through life. Even within the extremities there is a medial and lateral component. The inner aspect of the thigh and the inside of the arm are more medial and tend to be affected when the concern is more about how an external factor, person or event affects us personally.

Excess and Deficiency

The body is always processing and interacting with its internal and external environment as it continuously regulates, compensates, and distributes the ongoing influx of stimuli, sensations, nutrients, thoughts, etc. Health is maintained when the influx of stimuli and nutrients meets the needs of the body. When there is an imbalance between what is needed and what is received, symptoms manifest. Any manifestation of a symptom can be quantitatively looked at on the continuum of excess to deficiency; even other energetic concepts, such as internal/external, Yin–Yang, and the elements are often expressed quantitatively based on excesses and deficiencies. What exactly is too much or too little depends on the unique constitution and susceptibilities of each individual at any specific point and time. For example, a healthy individual with a lot of ‘fire’ will often desire and tolerate spicy food, more than an individual with very little fire. On the other hand, the healthy ‘fiery’ individual may find that when they are overwhelmed they do best to avoid spicy food.

The overall impact on health is based on the accumulation of all factors and their context. Like increases like, and opposites decrease each other. For example, hot spicy food, warm sunny weather, bright colored clothing, the emotions irritability and frustration all increase fire. Each of these alone might not be excessive but the effects are additive and together they cause the body to be in a state of excess. Individual factors will display a state of excess or deficiency as will the overall state of a person’s health. Also, whenever there is a state of excess in one aspect of an individual, another aspect often becomes deficient as a way of compensating or maintaining internal balance. For example, the consumption of excess coffee results in an inability to sleep, or when excess worry results in constipation (decreased movement in the bowels) (Frawley 1989, Maciocia 1989).

Excess

Excess is about too much. It can occur because of excesses in specific dietary and lifestyle behaviors, such as too much food, alcohol, cigarettes, anger, sadness, exercise, television, work, etc. A state of excess is caused by an imbalance between what you take in (digest or absorb) and what you let go of (secrete or express); both literally and figuratively. For the body to maintain health there needs to be a balance between the two. Excess also can occur by taking in too much from the external environment – excessive noise, light, stress, responsibilities, possessions, etc.

When in a state of excess, the circulation of energy is impacted and becomes congested or blocked. Excess manifests in symptoms such as intense, forceful movements, loud and full voice, intensity in thoughts or emotions, heavy breathing, pains that are worse with pressure, swelling and inflammation, or an increase in weight or size. A thick coat on the tongue and a rapid strong pulse indicate a state of excess (Kaptchuk 1983, Maciocia 1989). There also can be an excess of hormones, enzymes, stomach acid, and fluid. On a structural level, excess manifests as stiffness or heaviness. In order to treat an excess state, it is necessary to decrease the factor(s) contributing to the excess, and to promote the normal movement of energy or bodily fluids to the areas concerned.

Deficiency

In a deficiency state, an individual’s healing potential is compromised, and their resistance is low. The general symptoms of deficiency include white or pale complexion, fatigue, weakness and loss of strength, poor spirits, shallow breathing, pain relieved by pressure, too tired to talk, a low and feeble voice, excessive or spontaneous perspiration, and incontinence and insufficient hormones, enzymes, stomach acid or fluids such as urine, feces, or sweat. Deficiency causes a breakdown in tissues, organs, muscles, and structure. The tongue is pale and thin and the pulse feels weak (Maciocia 1998).

Yin–Yang

Yin–Yang is the single most important and distinctive concept of Chinese medicine (Table 5.1). This concept is extremely simple, yet very profound. It can be used to explain the quantitative and qualitative aspects of nature, physiology, pathology, and treatments. It is based on the flow of energy between two extremes. Yin–Yang is a continuum without borders or boundaries; it represents opposite yet complementary qualities.

Every phenomenon in the universe alternates through a cyclical movement of peaks and bases, and the alteration of Yin and Yang is the motive force of its change and development. Day changes into night, summer into winter, growth into decay and vice versa (Maciocia 1989).

Table 5.1 Yin–Yang (Kaptchuk 1983, Maciocia 1989, Beinfield & Korngold 1991)

| Yang energy | Yin energy |

|---|---|

| Superior, top-down | Inferior, bottom-up |

| Exterior, inside-out, centrifugal | Interior, outside-in, centripetal |

| Back | Front |

| Posterior-lateral surface | Anterior-medial surface |

| Front of the body – right side | Front of the body – left side |

| Back of the body – left side | Back of the body – right side |

| Left side of face | Right side of face |

| Superficial aspects of the body | Deeper aspects and organs in the body |

| Above the waist | Below the waist |

| Organs: gallbladder, stomach, small intestines, large intestines, urinary bladder and triple burner | Organs: heart, lungs, spleen, liver and kidneys |

| Breath – exhalation | Breath – inhalation |

| Qi, defensive Qi | Blood-body fluids, nutritive Qi |

| Masculine qualities | Feminine qualities |

| Purpose: function, activity, to receive, break down and absorb, generate, and to transform, transport and change | Purpose: structure, rest, to give, grow, regulate, conserve and store energy, spirit, fluids and blood |

| Characteristics: motion, outgoing, transforming, responsible, expressive, steady, aggressive, action-oriented, large firm and fleshy body, coarse features, high energy | Characteristics: yielding, nourishing, passive, feeling, maintenance, intuitive, receptive, creative, listening, gentle, flaccid body, delicate features |

| Signs and symptoms: excess, hot, dry, hard, rapid, expansion, heavy, restlessness, loud, stiffness, forceful movements, likes to stretch out, respiration is full and deep, sense of fullness, strong odor, pressure aggravates discomfort, hypertensive | Signs and symptoms: deficiency, cold, wet, soft, slow, quiet, contraction, sleepiness, weak, lack of strength, tired, likes to be curled up, excretions are thin, shortness of breath, sense of emptiness, pressure relieves discomfort, hypotensive |

| Push, extensor muscles | Pull, flexor muscles |

| Pathway into the material world | Pathway toward spirit. |

| Light, brightness | Darkness, shade |

| Sun, the cosmos | Moon, Earth |

| Summer, spring | Winter, autumn |

| East, south | West, north |

| To balance begin at the core and work outwards | To balance use heat, begin at the extremities and move to the core |

| Often associated with acute illnesses, rapid onset | Often associated with chronic illnesses, gradual onset |

The manifestation of Yin–Yang

Every component of an individual contains both aspects of Yin and Yang. These are seldom present in a 50/50 proportion, yet instead in a dynamic and constantly changing balance that is unique for each person (Kaptchuk 1983). For example, an individual who is more outgoing, aggressive, and strong would be considered Yang; whereas someone who was more nurturing, quiet, and of smaller build would be considered Yin. From a physiological point of view, this constant balancing is seen in the body’s innate ability to regulate sweating, urination, temperature of the body, breathing, etc.(Maciocia 1989). If Yin or Yang qualities are extended beyond their normal range of functioning, pathological changes will occur.

Diseases that have the qualities of heat, restlessness, and fullness indicate a preponderance of Yang; whereas, diseases that are characterized by weakness and coldness indicate more of a Yin condition. Acute diseases are often due to an excess of Yang. Chronic diseases, for the most part, are due to a Yin deficiency state (Maciocia 1989, Beinfield & Korngold 1991). The presence of a more predominant Yin or Yang is also apparent when the symptoms have a sidedness, a tendency to be more right or left, or more front versus the back. For example, a patient with pain and weakness in their left shoulder, a sensitive left hip, weak knees worse on the left, and an ear infection that started on the left side, would have a Yin imbalance. This imbalance might be caused by a lack of Yin qualities in a person’s life – e.g., nurturing, rest, creativity – or it can be due to an excess of Yang qualities – e.g., excessive work, exercise, alcohol; which in turn weaken Yin.

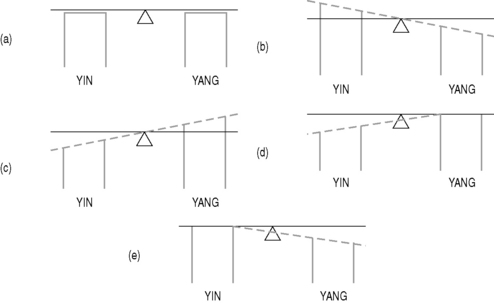

The presence of Yin–Yang can be thought of as a balance board (Fig. 5.4) that is in constant movement; as one increases the other decreases. When Yang is too high, Yin is deficient; when Yin is too high, Yang is deficient. Imbalances can also occur as a result of deficiency of either Yin or Yang. In this case, the predominant quality will lead to an apparent excess of other. For example, a deficiency of Yang will result in an apparent excess of Yin; a deficiency of Yin will result in an apparent excess of Yang.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree