Chapter 8 Surgical intervention

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Surgical–historical perspective

Modern surgery is the branch of medicine that comprises perioperative patient care encompassing such activities as preoperative preparation, intraoperative judgement and management, and postoperative care of patients (Phillips, 2007). Surgery as a discipline combines physiological management with an interventional aspect of treatment, which may be restorative, corrective, diagnostic or palliative (Table 8-1).

Table 8-1 Common indications for surgical procedures

| Indication for surgical procedure | Example |

| Incision | Open tissue or structure by sharp dissection |

| Excision | Remove tissue or structure by sharp dissection |

| Diagnostics | Biopsy tissue sample |

| Repair | Closing of a hernia |

| Removal | Foreign body |

| Reconstruction | Creation of a new breast |

| Palliation | Relief of obstruction |

| Aesthetics | Facelift |

| Harvest | Autologous skin graft |

| Procurement | Donor organ |

| Transplant | Placement of donor organ |

| Bypass/shunt | Vascular rerouting |

| Drainage/evacuation | Incision of abscess |

| Stabilisation | Repair of a fracture |

| Parturition | Caesarean section |

| Termination | Abortion of a pregnancy |

| Staging | Checking cancer progression |

| Extraction | Removal of a tooth |

| Exploration | Invasive examination |

| Diversion | Creation of a stoma for urine |

Surgical procedures are carried out in hospitals, day surgery units or surgeons’ rooms. A surgical procedure may be invasive, minimally invasive, minimal access or non-invasive in nature. Any invasive or minimal access procedures involve entry into the body through an opening in the tissues or a body orifice (Phillips, 2007). Non-invasive procedures are frequently diagnostic and do not enter the body. Advances in diagnostic methodologies and drug therapies enable more individuals to be considered for surgery; however, each patient and each procedure is unique. Surgery cannot be considered always completely safe, patient outcomes are not constantly predictable and the surgical team must, at all times, be prepared for the unexpected.

All surgery has clearly defined principles of the operative technique (Phillips, 2007).

These principles are listed below.

Sequence of surgery

Additional knowledge required by the surgical team includes:

Stages of the surgical procedure

Every surgical procedure, whether invasive or minimally invasive, and regardless of the rocedure undertaken, will follow a set sequence that can be broken down into five stages, as shown in Table 8-2 (Richardson-Tench & Martens, 2005).

Table 8-2 Five stages of the surgical procedure

| Stage | Procedure |

| I | Open |

| II | Dissection and exposure |

| III | Exploration and isolation |

| IV | Repair—revise, excise or replace |

| V | Close |

Stage I—Open

Stage IV—Repair: excision, revision or replacement

Haemostasis and irrigation

In preparation for closure, the surgeon will examine the operative site, controlling any bleeding with ligation and/or electrosurgery. To assist in the examination for bleeding, some surgeons will fill the abdominal cavity with a warm solution, such as normal saline. If an anastomosis has been performed, this is examined to ensure that it is secure. The surgeon carries out a final check to ensure that no items are left behind. Oozing from the operative site may require a drain to be inserted, such as a closed wound suction system.

Stage V—Close

The closing stage comprises wound closure (including surgical counts) and the application of a dressing. The principles related to the division of tissue (Table 8-3) must be understood by all members of the surgical team. This knowledge is of particular importance for the instrument nurse and the nurse assisting the surgeon.

Table 8-3 Principles of division of tissue

| Procedure | Rationale |

| Providing exposure | |

| Stabilisation of anatomical structures | |

| Use of retractors, grasping instruments and other devices | • Self-retaining retractors are normally used on muscle; smooth blades prevent tearing; toothed blades hold fasciae, subcutaneous tissue, skin. |

| Clamping tissue | |

| Grasping tissue |

The division of tissues is explained below in relation to a laparotomy.

Wound closure

The body is made of many different tissue layers, each having individual characteristics and roles. Historically, every layer was sutured closed. However, with research and the advent of synthetic materials, this practice has been deemed unnecessary in the majority of patients (Phillips, 2007).

Muscle

The next layer of tissue encountered is muscle. Three layers of muscles—the rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, and the transverse abdominis—cover the abdominal cavity. The layering effect provides greater strength. The muscle may or may not be sutured upon closure (Phillips, 2007).

Subcutaneous layer

Closure of the subcutaneous layer will be dependent on the surgeon and the patient’s physical characteristics. One of the objectives of wound closure is to remove dead space and, in doing so, achieve better wound closure, as discussed in Chapter 7. The subcutaneous layer is one layer that, if left unsutured, will provide dead space, the presence of which allows tissue fluids to accumulate, which can delay wound healing. Absorbable suture material that is broken down by hydrolytic action is preferred for suturing of the subcutaneous or subcuticular tissues.

Skin

An absorbable monofilament suture material with a cutting needle using a subcuticular suturing technique is the preferred option for skin closure as the sutures do not require removal and there is less associated tissue reaction. The skin may also be closed by interrupted sutures using an absorbable or non-absorbable suture material. Skin staples or skin glue can also be used, despite not belonging to the absorbable, monofilament group. In conjunction with these skin closure materials, sterile adhesive strips may be added to provide extra support to the skin edges. Tension sutures may be required to provide additional support and relieve undue strain on the wound for patients in whom wound healing may be compromised; for example, in elderly or obese patients or those on chemotherapy (see Ch 7) (Dunscombe, 2007).

Instruments

Instrument categories

Some basic manoeuvres are common to all surgical procedures. The surgeon dissects, resects or alters tissue and/or organs to restore or repair body functions or body parts (Phillips, 2007). Surgical instruments are designed to act as the tools that the surgeon needs for each manoeuvre and are commonly categorised into five major groups. Although different labels may be attributed to these groups, they are generally categorised as:

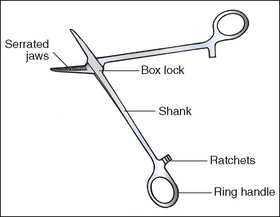

Anatomy of a ring-handled clamp

The features of a ring-handled clamp are outlined below as an example of a surgical instrument (Fig 8-1).

Cutting and dissecting instruments

Scalpels

Scalpel blades are a potential sharps hazard and, therefore, scalpels are passed in a receptacle (AORN, 2005a). In certain surgical specialties, such as cardiac, vascular and neurosurgery, it is not possible to pass the scalpel blade in this manner. In these circumstances, the instrument nurse should grasp the top of the handle, passing the handle towards the surgeon with the actual blade pointing downwards.

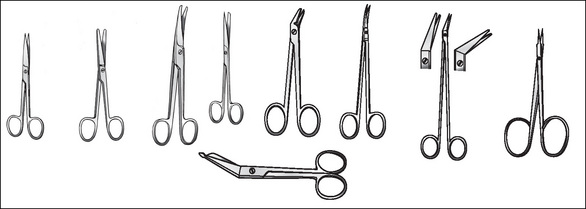

Scissors

Scissors may open and close or have a spring action. The spring action provides better control and more precision, which is important when dissecting delicate tissues, such as those within the eye. Handles can be short or long, with blades straight or angled. Four types of scissors (Fig 8-2) are available:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree