SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

• Physiological changes in stress

• The stressful personality

• Psycho/social changes in stress

• Life events and stress

• Post-traumatic stress disorder

• Burnout

• Causes of stress

• Relaxation and rest

• Sleep

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

• Assessing stress

• Identifying common sources of stress

• Stress management strategies

• Work-related stress in nursing

• Assessing sleep

• Aiding sleep

PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL KNOWLEDGE

• The terms and conditions of paid carers

• Employment-related stress in health and social care

• Service users and informal carers

PERSONAL AND REFLECTIVE KNOWLEDGE

• Time management

• Case studies

INTRODUCTION

Although stress, relaxation and rest are separate concepts there is a high degree of interdependence. Fundamental to all, however, is the influence of psychological stress. Consequently, in this chapter emphasis has been placed on developing an awareness of recognizing and managing stress, as it is from this foundation that understanding of relaxation and rest can develop.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

This section addresses the nature of stress, its effects on individuals and the role it plays in the lives of everyone, together with the physiological, psychological and social changes that occur in response. The consequences of exposure to very stressful events and prolonged exposure to stress are focused on when examining the conditions of burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder. Finally, the concepts of relaxation, rest and sleep are discussed and their relationship to stress is explored.

Care delivery knowledge

This section focuses on strategies that can be used in the assessment and management of both psychological stress and sleep. First stress in clients is addressed. The reasons why clients may suffer from stress help to identify what should be assessed and why, and these are examined in detail. Clients’ carers are also likely to experience stress and common reasons why this is, and the signs that indicate this, are also explored.

The workplace is potentially a very stressful environment. This is probably first recognized by the effects on employees. Consequently, strategies for developing an awareness of your own level of stress, and also for identifying signs of stress in colleagues are discussed together with methods of management.

The final part of this section focuses on assessing sleep and examining ways that sleep can be promoted.

Personal and reflective knowledge

This chapter has been designed to enhance learning through developing self-awareness. The final part of this chapter looks at time management as a means of taking control of stressors and helps you to develop a stress management routine.

On pages 222–223 are four case studies, each relating to one of the branch programmes. You may find it helpful to read them before you start the chapter to use as a focus for your reflections.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

Think about being stressed. Then think about being relaxed. Are they opposite ends of the same scale, or are they more difficult to define? Is stress always bad? Is being relaxed the same as resting? Can you relax and be active at the same time?

Answering these questions can be confusing as at face value the terms seem to be conflicting. So, to begin this chapter the concepts of stress, relaxation and rest will be examined in greater detail.

CONCEPTS OF STRESS

Most contemporary work into stress and stress management is influenced by the fundamental works of Seyle, 1984 and Hebb, 1955. It was Seyle’s work that led medicine to become interested in stress (Pacak & Palkovits, 2001) and it is his definition of stress as ‘the non-specific response of the body to any demand’ (Seyle 1984: 74) that has become used widely in both research and practice.

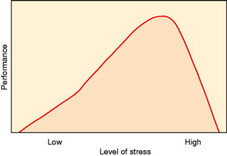

In vernacular use the term stress is usually associated with negative feelings. This is not always correct though, as a certain amount of stress is a normal part of day-to-day life. Hebb (1955) originally demonstrated this in the arousal curve (Fig 9.1), where an individual’s performance is seen to increase in proportion to the level of arousal. Once the individual’s maximum capacity for arousal is exceeded though, performance falls and adverse effects on an individual’s health begin.

|

| Figure 9.1 (from Hebb 1955). |

Although since surpassed by more complex models, what is important about Hebb’s work is that it shows all individuals require a certain amount of stress to achieve optimal functioning. Once this point is exceeded though, an individual’s ability to function deteriorates rapidly and this is also associated with negative effects in health. This explains why people in very demanding, high-pressure jobs are at risk of developing stress-related diseases.

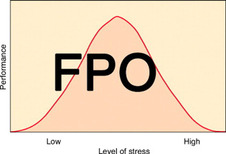

Hebb’s work explains the relationship between exposure to excessive stress, performance and illness; however, people who have jobs that offer little in the way of stimulation also develop stress-related diseases. This apparent contradiction to Hebb’s arousal theory was proposed by Sutherland & Cooper (1990) and latterly by Zivnuska et al (2002). While they agreed with Hebb that over-stimulation caused excessive stress, they found that stress also could be caused by under-stimulation. This led to the evolution of Hebb’s arousal curve into an inverted U which identified an optimal level of performance in the centre of excessive levels of stress characterized by under-stimulation and over-stimulation (Fig. 9.2) and shows that boredom is just as stressful as over-stimulation.

|

| Figure 9.2 (from Sutherland & Cooper 1990). |

Seyle (1984) took a slightly different view on the nature of stress. He argued that stress could be positive or negative. Positive stress he named eustress (from the Greek word ‘eu’; good) and it is associated with feelings of excitement or euphoria. Conversely, negative stress was named distress (from the Latin word ‘dis’; bad). Although the body undergoes similar immediate physiological changes in both types of stress, it is the long-term effects of distress that are damaging. Seyle’s definition integrates well with the inverted U hypothesis in that individuals require a certain amount of arousal to perform optimally (whether this occurs when working or when relaxing). This occurs in eustress stimulation. If the arousal becomes too great or too little, however, then eustress is replaced by distress.

Often, whether stress is positive or negative is related to whether the individual has control of the stressor (the object triggering the stress). Stress that occurs where the individual retains control is positive and exhilarating. On the other hand, where the individual has little control of the threat then the experience is negative and damaging. This is referred to as the locus of control, a lack of which has been linked to poorer health outcomes (Schmitz et al., 2000, Coyne, 2006 and Sjöström-Strand and Fridlund, 2007). See Evolve 9.1 for more information and an exercise to develop your awareness of this.

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN STRESS

The General Adaptation Syndrome

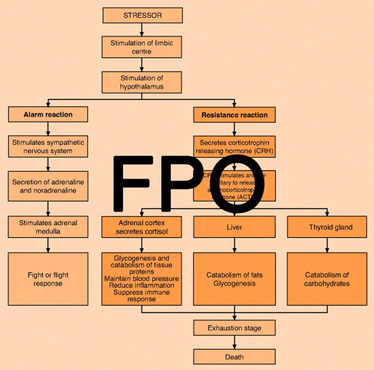

Once a stressor is detected as a potential threat the hypothalamus is stimulated, which in turn invokes the General Adaptation Syndrome. This is a physiological response described by Seyle (1984), the framework of which continues to be accepted as valid. It occurs over three consecutive stages (Fig. 9.3).

|

| Figure 9.3 (adapted from Seyle 1984 by kind permission of McGraw-Hill). |

1. Alarm reaction

This is a very rapid physiological response, activated by the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal medulla, which prepares the body for action. It causes an increase in the secretion of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), invoking the fight or flight response causing the physiological changes summarized in Table 9.1, which prepare the body to either confront and fight, or to escape quickly from, the stressor.

| System | Effect | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory system | Increased heart rate and force of contraction Peripheral vasoconstriction | Concentrates blood in the body core, increases blood pressure and increases the flow of blood to the large skeletal muscles that will be used either in fighting or running away |

| Respiratory system | Increase in respiration rate Dilation of bronchi | Increases oxygenation of the blood, providing the muscles with vast amounts of oxygen in anticipation of the increased aerobic respiration involved in major exertion |

| Eyes | Pupil dilation | Allows more light into the eyes, resulting in better vision |

| Skeletal muscles | Increased tension | Quicker response |

| Excretory system | Increased micturition | Removes excess fluid to reduce body weight and allow a quicker response |

| Digestive system | Diarrhoea Vomiting Dry mouth | Reduces weight Reduces weight Prevents eating and adding to weight |

| Skin | Sweat gland activation | Increases cooling in anticipation of muscle activity |

2. Resistance reaction

The alarm reaction is followed by the resistance reaction. This is a long-term response brought about by a chain of hormones originating in the hypothalamus (see Fig. 9.3). It begins with the release of corticotrophin releasing hormone which stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotrophic hormone. In turn this stimulates the adrenal cortex to increase the secretion of cortisol. The action of cortisol increases glycogenesis and catabolism of body proteins leading to hyperglycaemia, which provides energy to sustain the response.

Cortisol also suppresses the inflammation response, enabling the body to continue this reaction if it becomes damaged. It also constricts the peripheral blood vessels and maintains blood pressure within the skeletal muscles and vital internal organs should blood loss occur though damage to the body surface.

Cortisol also suppresses reconstruction of connective tissue and the immune system though, which can have serious adverse consequences in the long term. In practice, this is likely to be of particular significance during recovery from illness or surgery.

3. Exhaustion

This is the final stage of the General Adaptation Syndrome. It occurs following prolonged exposure to stressors and, if continued, leads to illness and, eventually, death. Prolonged use of the General Adaptation Syndrome, as occurs in stressful environments where there is no escape, therefore has adverse consequences for the health of individuals.

THE STRESSFUL PERSONALITY

Some individuals consistently respond to stressors in similar ways. The most common classification is that of Friedman & Rosenman (1974) who identified two personality types: type A and type B (Fig. 9.4). The type A personality is characterized by extreme competitiveness and an inability to place stressors in perspective. They routinely work against the clock, find it difficult to say ‘no’ or to delegate, and consequently find themselves with multiple commitments. Consequently, they are unable to fit all their demands into the available time and they end up juggling tasks, switching from one to another, without completing any. This is worsened by a lack of direction. Rather than taking a systematic approach to problem solving, they attempt to solve problems without first identifying the goals. They are also fiercely competitive, leading them to appear aggressive, and they react to minor irritations in the form of temper tantrums. By way of contrast, the second personality type, type B, is the antithesis to type A. They are almost unconcerned when confronted by stressors.

|

| Figure 9.4 |

Type A and type B are in reality two extreme points of a scale. Most people have traits of both personality types and fit on a point somewhere along it. Significantly though, Friedman & Rosenman, and latterly Myrtek (2001), found that people with more type B characteristics were less susceptible to coronary heart disease.

It is not just the circulatory system that is affected by continued exposure to stressful events though. Figure 9.3 shows that the action of cortisol suppresses the immune response. This was demonstrated by Brosschot et al., 1998 and Segerstrom and Miller, 2004, who found that when individuals were exposed to stressors they were unable to control, their immune systems became suppressed. Similarly, Pruessner et al (1999) reported that individuals who were in situations where they experienced high distress and low self-esteem had higher serum cortisol than would be expected, which in turn suppressed their immune systems. A suppressed immune system renders the individual less able to fight off disease. Often people find that when they are tired, such as when they have been working for a long time without a holiday break, they become more susceptible to minor infections such as colds, and that once they contract an infection it takes longer than usual to recover. Indeed, the incidence of sickness in the workplace is an indicator of employee stress.

The immune system also protects the body against more sinister diseases though. Following major life events an extreme stress response is invoked and it has been observed that for around a year afterwards people have an increased susceptibility to developing cancers (Lillberg et al., 2003 and Thaker et al., 2007).

Continued exposure to stressful events

One of the most obvious effects of continued exposure to stress occurs in the circulatory system. During the General Adaptation Syndrome, heart rate and blood pressure increase and after time this can damage the circulatory system as it tries to compensate. This was demonstrated in the fundamental research of Friedman & Rosenman (1974), although studies continue to report associations between high levels of psychological distress and coronary heart disease (Bosma et al., 1997, Stansfeld et al., 2002 and Sjöström-Strand and Fridlund, 2007).

Furthermore it has been identified that if type A behaviour is accompanied by hostile behaviour, then these individuals are the most likely develop coronary heart disease (Barefoot et al, 1995).

PSYCHO/SOCIAL RESPONSES TO STRESS

Psycho/social responses to stress vary according to the level of threat. A mild level of stimulation, where the individual remains in control (eustress), is accompanied by positive feelings. As the level of stress increases though, the pleasure changes to a feeling of being overwhelmed (distress). The ability to function effectively decreases and although individuals may be aware of what is happening, they find it difficult to engage in problem-solving thinking. Consequently, individuals find they have ever-increasing demands that they are unable to meet, which in turn perpetuates their distress.

Due to the fight or flight reaction that this invokes, individuals may become short tempered and aggressive, and often their social interactions will reflect this increased hostility where they may experience frequent arguments and become intolerant of others. In the long term, this causes their interpersonal relationships to deteriorate (Vernarec 2001), making things worse, and individuals can quickly find themselves locked into a stress cycle.

MENTAL DEFENCE MECHANISMS

Often, in response to stressors, individuals attempt to cope by using mental defence mechanisms (Table 9.2). These were originally identified by Freud (1934), who claimed they provided a defence against conflict, and they have since been developed by many other psychologists. In the short term mental defence mechanisms are a healthy response and they buy time for the individual to adjust. As they do not alter the cause of the distress (they only alter an individual’s interpretation of it) they involve a degree of self-deception and prevent the individual from addressing the problems. Consequently, prolonged use of mental defence mechanisms is unhealthy and potentially damaging.

| Mechanism | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Denial | When reality is too unpleasant or painful to face then individuals may deny that it really exists. In some circumstances this is a healthy process as it allows the individual time to come to terms with the problem. Indeed it is the first stage of the grieving process (Kubler Ross 1975). In other situations denial may be more serious (see example) | A woman may deny that she could have a serious illness and may delay seeking medical help for a lump she has recently found in her breast |

| Displacement | When it is impossible to address the cause of stress then anger may be redirected on another, innocent but reachable object | You may have been given a hard time by your boss to whom you are unable to retaliate. When you return home you immediately have a blazing argument with your partner |

| Intellectualization | To use intellectual powers of thinking, analysis and reasoning to detach oneself from emotional issues | For people working in life or death situations, such as in high dependency units, this defence mechanism may be necessary for survival. If the emotional bluntness extends into other areas of the individuals’ lives, however, then the mechanism becomes problematic |

| Projection | Blaming someone else for how you feel | The ward manager who is unable to manage the ward effectively may blame the situation on incompetent staff |

| Rationalization | To find an acceptable explanation for an act that you find unacceptable | ‘It’s in the overall best interest’ ‘You have to be cruel to be kind’ ‘I don’t really care that I lost the interview. I didn’t really want the job anyway’ |

| Reaction formation | To conceal what you really feel by thinking and acting in the opposite way | Some people who have an issue in their life about which they feel uncomfortable may campaign against the issue For example, individuals who have led promiscuous lives may campaign strongly for the sanctity of family values |

| Regression | Individuals engage in behaviours from an earlier, more secure, life stage | Losing your temper and engaging in tantrums when things go wrong Eating when feeling stressed |

| Repression | Painful thoughts are forced into the unconscious. Although they are out of the conscious they may resurface in dreams | An accident victim may utilize repression to have no recollection of the events surrounding the accident |

| Sublimation | To redirect the energy from unacceptable sexual or aggressive drives into another socially acceptable activity | Unacceptable aggressive energy focused into a sporting activity This may not always be a positive mechanism. For example, an ambitious manager may utilize sublimation to secure promotions at the expense of family and social commitments |

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a severe response to an extremely threatening or catastrophic event or situation (e.g. being a victim of a violent crime or witnessing a major disaster) that occurs within the 6 months of the triggering factor (World Health Organization 1992).

The main features of PTSD are:

• Flashbacks where individuals relive the experience during nightmares. Occasionally, when awake, they may also feel that the situation is about to recur.

• Emotional numbness and detachment from others.

• Hypervigilance and an enhanced startle reaction.

• Avoidance of anything resembling the triggering event.

• Confusion, anxiety and depression; there may be attempts to commit suicide.

Additionally, a number of other symptoms can occur including insomnia, headaches, ulcers and circulatory problems. Sometimes individuals blame themselves for the incident and suffer additional fear and guilt. Furthermore, to compensate individuals may abuse alcohol or other drugs, which may lead to dependence.

The most effective methods of treatment for PTSD are early supportive interventions that avoid focusing on the traumatic event. Following 1 month, however, all individuals involved in the event should be screened for PTSD. Those identified as suffering can then be offered targeted interventions, which should also include support for the sufferer’s family (NICE 2005). Chapter 12, ‘Aggression’, contains further information on managing PTSD.

BURNOUT

When people are exposed to stressors for prolonged periods they can develop a condition called burnout. People suffering from burnout feel drained, emotionally blunt and cynical. As burnout is usually work-related; sufferers feel devalued by their employers and trivialize any achievements they make. Consequently their relationships within work deteriorate and the effects can also spill out of the workplace where they may struggle to maintain social contacts and partnerships (Leiter & Maslach, 2005).

Most employees in health and social care work with ill people for prolonged periods, often with inadequate resources or support. These are powerful sources of distress which predisposes to burnout (Schmitz et al., 2000 and Leiter and Maslach, 2005).

Burnout is aggravated by the highly competitive, insecure workplaces that are common in contemporary society, where working long hours – frequently for low pay – are seen as normal (Leiter & Maslach, 2005). This leads individuals to feel that their feelings are as a result of weakness in their character, thus compounding their problem as they are reluctant to seek help (Payne 2001).

CAUSES OF STRESS

The causes of stress (stressors) are the result of an individual’s interpretation of a phenomenon. Holmes & Rahe (1967) discovered that certain life events invoked differing amounts of stress and that their effects accumulated. Their classification of the significance of these stressors forms the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) (Box 9.1), an instrument which is still commonly used. On this scale, according to the amount of stress invoked by a stressor, a greater weighting is ascribed to it.

Box 9.1

| 1. Death of spouse | 100 |

| 2. Divorce | 73 |

| 3. Marital separation | 65 |

| 4. Jail term | 65 |

| 5. Death of close family member | 63 |

| 6. Personal injury or illness | 53 |

| 7. Marriage | 50 |

| 8. Loss of job | 47 |

| 9. Marital reconciliation | 45 |

| 10. Retirement | 45 |

| 11. Change in health of family member | 44 |

| 12. Pregnancy | 40 |

| 13. Sex difficulties | 39 |

| 14. Gain of new family member | 39 |

| 15. Business readjustment | 39 |

| 16. Change in financial state | 38 |

| 17. Death of close friend | 37 |

| 18. Change to different line of work | 36 |

| 19. Change in number of arguments with spouse | 35 |

| 20. Mortgage over $10 000 | 31 |

| 21. Foreclosure of mortgage or loan | 30 |

| 22. Change in responsibilities at work | 29 |

| 23. Son or daughter leaving home | 29 |

| 24. Trouble with in-laws | 29 |

| 25. Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| 26. Wife begins or stops work | 26 |

| 27. Begin or end school | 26 |

| 28. Change in living conditions | 25 |

| 29. Revision of personal habits | 24 |

| 30. Trouble with boss | 23 |

| 31. Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| 32. Change in residence | 20 |

| 33. Change in school | 20 |

| 34. Change in recreation | 19 |

| 35. Change in church activities | 19 |

| 36. Change in social activities | 18 |

| 37. Mortgage or loan of less than $10 000 | 17 |

| 38. Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| 39. Change in the number of family get-togethers | 15 |

| 40. Change in eating habits | 15 |

| 41. Holiday | 13 |

| 42. Christmas | 12 |

| 43. Minor violations of the law | 11 |

A score over 300 is associated with an increased risk of developing a stress related disease (Holmes & Rahe 1967).

(from Holmes & Rahe 1967, by kind permission)

To use the scale, each stressor that has occurred within the previous year is identified. By summating the rating ascribed to each it becomes possible to assess an individual’s level of stress. For clinical work, Holmes & Rahe found that a score over 300 was associated with an increased risk of developing a stress-related disease.

Following the loss of a partner, the surviving spouse often becomes ill and may die. Lichtenstein et al (1998) found people most at risk were those bereaved between 60 and 70 years. Similar findings were reported by Hart et al (2007) who found the mortality rate among surviving spouses of all ages to be raised significantly.

Within the context of stressful life events, surviving partners, particularly within the older age group, are likely to have: recently experienced retirement, a reduction in income, adjusted to their own ill health, supported the deceased partner and the demands of their illness, experienced the death of the partner, met the financial and family demands following the death and undergone their own grieving, from both the loss of their partner and, according to Narayanasamy (1996), from feeling abandoned by their spiritual beliefs.

Try using the SRRS to calculate the effect of the above stressors on an individual. You will find a web-based SRRS calculator in Evolve 9.2 on the Evolve website.

Even when experiencing similar stressors some individuals appear to be able to cope better than others. By using Hebb’s model of arousal (Hebb 1955) in conjunction with the SRRS (Holmes & Rahe 1967), it is possible to see why one individual may be unaffected by an incident while to another individual the effect of the same incident may be catastrophic. By using the SRRS to review life events that occurred over the previous year, it could be found that one individual had an accumulation of many stressors while the other had comparatively few. Thus exposure to the same new stressor could push the first individual into overload whereas the other had sufficient coping reserve.

The SRRS was developed over 40 years ago and has been criticized for its inability to predict the specific type of illness and for relying on retrospective data. Despite this, it remains a reliable instrument and enjoys extensive contemporary use in practice and research (Scully at al 2000). There are two major limitations of the scale, however. First, it only addresses long-term stressors and fails to take into account short-term stressors such as being late for work or sitting in a traffic jam. Short-term stressors, or ‘hassles’, invoke a severe stress response but only for a short period (Lazarus et al 1985). Being out of the individual’s control though, they invoke distress and have adverse effects on health.

The second shortcoming of the SRRS is forwarded by Le Fevre et al (2006), who argue that it is difficult to generalize individuals’ esoteric experiences of stress. Holmes & Rahe (1967) assumed that a stressor causes the same amount of stress for everyone. This is the engineering model of stress and is demonstrated in Figure 9.5 where the spider is interpreted identically by subject A and subject B.

|

| Figure 9.5 |

Le Fevre et al (2006) argue this model is too simplistic, and that to gain a true understanding of the nature of stress, the stressor must be appraised from the context of the perceived threat (or excitement) that it poses; i.e. the level of stress depends on the amount of threat the individual thinks it poses. This is represented in Figure 9.6 where subjects A and B are exposed to the same stressor as before but, because of the meaning subject B attaches to the spider in that particular context, the interpretation of threat is greater for subject B than subject A.

Therefore, to understand an individual’s stress also requires measuring hassles and gaining an understanding of their interpretation of stressors (Lazarus et al., 1985, Hahn and Smith, 1999, Narayanasamy and Owens, 2001 and Le Fevre et al., 2006). Applied to clinical practice, this suggests that the use of the SRRS to measure long-term stress is useful in so much as it identifies a baseline of background stressors. From this baseline, however, the effects of day-to-day stressors and the interpretation an individual attaches to the nature of stressful experiences must also be added.

RELAXATION AND REST

Relaxation and rest are linked strongly with stress. Sometimes relaxing is simply doing something different from work. Thus, relaxation can be active or recreational, for example walking or playing a sport (eustressful activities). At other times relaxing means reducing physical activity (such as sunbathing).

Relaxation is generally the precursor to rest. Rest is the period when the body does minimum activity; allowing restorative processes to happen and following which the individual feels refreshed or rested. Often this coincides with sleep.

Although there is a close relationship between stress and relaxation, they are not opposite ends of a scale. It depends on context and the amount of control the individual has over the situation. Sitting down and doing nothing in a quiet room at home may be relaxing; however, sitting and doing nothing in an airport because your flight has been delayed is far from restful! Similar to stress then, relaxation and rest need to be examined in context.

SLEEP

Sleep is associated with resting. It is a recurrent natural condition where consciousness is temporarily lost and bodily functions are partly suspended. It ends either by a natural return of consciousness or by external stimulation, for example by an alarm clock.

There are five stages in the sleep cycle (Box 9.2). Initially individuals move through stages 1 to 4. This is followed by a period of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, a lighter level of sleep which is when dreaming occurs and is also when the individual will change position in bed. The sleep cycle then returns to stage 2 and repeats until the individual awakens. Each cycle lasts around 90 minutes in an adult, although the length of time spent at each stage alters throughout the night; during the early night the percentage spent in stages 3 and 4 is larger in comparison to REM sleep, while in the later hours of sleep the proportion of REM sleep increases.

Box 9.2

| Stage 1 | Falling asleep. The individual becomes drowsy and barely conscious, although any slight sound would arouse him or her. Electroencephalograph (EEG) recordings show alpha waves that are associated with being awake |

| Stage 2 | The individual is now asleep. Skeletal muscles are relaxed and movements are still; however, the individual can be roused easily. The EEG shows the appearance of slow waves called K-complexes, as well as bursts of rapid waves known as sleep spindles (Borbely 1987). Stage 2 accounts for more than half the time spent asleep |

| Stage 3 | The individual is completely relaxed and is difficult to arouse. Familiar noises, such as a child crying, can awaken the individual, however. EEG waves become slower and larger and are known as delta waves (Borbely 1987) |

| Stage 4 | Deep sleep. The individual rarely moves and is difficult to awaken. An increase in the percentage of delta waves is noted on EEG recording |

| Stage 5 | Rapid eye movement (REM) or paradoxical sleep. This is characterized by a period of light sleep during which dreaming is thought to mainly occur. For Freudian analysts, dreaming is a symbolic process where the unconscious conflicts are brought to the conscious for resolution |

(adapted from Horne 1988, by kind permission of Oxford University Press)

Circadian rhythm

Why we feel tired at night and sleep when we do is largely controlled by the circadian rhythm. When deprived of light or other sources of time-keeping humans adopt a sleep–wake routine which cycles approximately every 25 hours. This is the circadian rhythm, although in real life it is modified in response to triggers called zeitgebers (time cues). These synchronize the circadian rhythm of an individual with the environment, and the most powerful of them are of an informative or social nature (Sharma & Chandrashekaran 2005). Examples are:

Activity within circadian rhythm cycles also varies between two broad personality types:

• ‘Larks’ who awaken early and do their best work in the morning. However, they become tired by early evening and do not function as efficiently.

• ‘Owls’ who have difficulty rising in the morning, often have difficulty facing breakfast and do not really perform at their best until late afternoon and evening. Owls also tend to go to bed late.

Patterns of sleep

Although sleeping once at night is normal in most North European countries, one type of sleep pattern is not relevant for all cultures. For example, in some Mediterranean cultures a siesta is taken in the hottest part of the day and in China workers are expected to have a sleep in the middle of the day as part of the lunchtime break. However, it is common in Western society for individuals to receive insufficient sleep. Taheri et al (2004) reported that this can lead to an endocrine imbalance resulting in an increased appetite and, in turn, weight gain; in nurses working rotational shifts, Muecke (2005) reported this resulted in a decrease in performance which in turn had ramifications on patients’ safety.

The normal pattern of sleep also changes with age (Table 9.3). However, within these norms individuals’ needs for sleep differ. It is therefore impossible to generalize exclusively from these data and it is the individual who best knows whether or not they are receiving enough sleep.

| Age | 2 months | 3 years | 25 years | 75 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of sleep | 18 hours | 13 hours | 8 hours | 5 hours in 24 hours |

| Pattern of sleep | Asleep between daytime feeds | Night sleep and day nap | Night sleep | Night sleep and day nap(s) |

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

Although individuals respond to stress in their own esoteric ways, some responses are universal. By measuring these it is possible to assess the degree of stress an individual is experiencing and to consider the ramifications on their ability to relax and rest. The first part of this section therefore begins by outlining tools to measure stress. This progresses to examine common causes of stress affecting clients, carers and care professionals and at the end of this section, strategies for managing stress are discussed.

The second part of Care Delivery Knowledge discusses how sleep may be assessed and outlines approaches to use to promote sleep.

METHODS OF ASSESSING STRESS

Physiological measures

Because of the relationship between psychological stress and physiological disturbance, demonstrated by the General Adaptation Syndrome (Seyle 1984), it is possible to assess stress using physiological measures such as the electrical conductivity of the skin, heart rate and blood pressure. The disadvantage of physiological measures is that they do not explain why the individual feels stressed. Furthermore, the process of recording may be distressing for individuals and this may result in an inaccurate measurement (Gerin et al 2006). Therefore, although it is important to understand physiological indicators of stress, to understand the nature of the stress requires additional information.

Immediately on admission most patients have their baseline observations recorded.

• Referring to the General Adaptation Syndrome, what are advantages and disadvantages of this?

• How might the disadvantages be addressed?

• Go to http://www.bpassoc.org.uk/BloodPressureandyou/Medicaltests/whitecoateffect and consider why nurses should take into account the ‘white coat effect’ when recording blood pressure.

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale

The SRRS (Holmes & Rahe 1967) was discussed in the Subject Knowledge section of this chapter. It is inappropriate to use only this instrument, as it may not record all the factors that are causing the current period of distress. Nor does it measure the amount of stress felt by the individual. However, this is an excellent instrument to gain insight into the background of an individual’s situation, and to provide avenues for further exploration.

Stress scales and diaries

Because it is experienced by an individual, and not outwardly observable, stress is very difficult to measure. A very similar construct with equally difficult measurement is pain. Because of its subjective nature, the amount of pain patients experienced was frequently misjudged and in consequence they were given inadequate analgesia. This led to the development of pain scales where patients indicated the severity of pain they felt ranging from ‘No pain’ at one end to ‘Unbearable pain’ at the other. Although these are not decisive measures of pain, they indicate the effectiveness of pain management strategies, particularly if they include some form of scaling.

As stress is also a subjective phenomenon, to gain insight into stress from an individual’s perspective, instruments should measure the nature, frequency and intensity of the experience. The combination of scales and diaries to indicate the time, nature and precipitating factors make these useful instruments to assess the nature of stress that clients experience.

In research into the experiences of student nurses, a modification of pain scales proved a very effective measure. An instrument was designed around a 10-point scale. Prompts were included for guidance and ranged from 0, which indicated no stress at all, to 10 which indicated feeling totally overwhelmed, reflecting Seyle’s (1984) model of stress with lower scores indicating eustress and higher scores distress. These were supplemented with brief diary notes and over a period of time stress profiles were generated for each student. Combining these data subsequently allowed identification of particularly stressful periods of the pre-registration nursing course which could be addressed in future course planning and provision of supportive services (Howard 2001).

IDENTIFYING COMMON SOURCES OF STRESS

For clarity, this section examines separately stress that occurs in clients, in their relatives and in the workplace.

Stress in clients

Stress that clients experience may be:

• a primary reason for referral

• a cause of, or a contributory factor to, an illness

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access