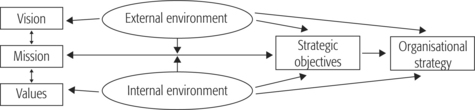

CHAPTER 12 Strategy and organisational design in health care After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to: The purpose of this chapter is to provide a contextual framework for examining strategy and organisational design in health care. Given the complex and changing nature of the environment in which health care organisations must perform — where increasing demand for services, insistence on cost control, clamour for the latest technological advances, conflict between professional groups, and importance of quality all converge — managers must actively engage in designing organisations that work best and help in maintaining high performance. Fundamentally, work is divided between areas, groups and individual employees to enhance the organisation’s ability to achieve its goals in an integrated, efficient and effective manner and to enable it to respond flexibly to a constantly changing and volatile environment. Unfortunately, there is no one best way to structure an organisation, as there are several factors such as external and internal environment, size of organisation, mission and objectives which influence decisions made concerning the design. It is not unusual for organisations in similar circumstances to be structured differently, as the same design is not necessarily the best for all. While keeping in mind the primary function of the organisation, a thorough analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of each design should be undertaken in order to assess whether it will be appropriate to the organisation’s overall strategy (McLaughlin 1996). The development of an organisational design and ways of operating are influenced by the varying nature of each organisation and its primary function. Using these two dimensions, Katz and Kahn (1978, p 145) describe the following four types of organisation: In the real world, organisations may perform a number of functions and so do not fall easily into one category. However, generally they are driven by one primary function, with others undertaken in a secondary capacity. Working within a dynamic health care environment, traditional maintenance organisations may find that they need to assume a more productive approach so that they can generate income to boost their funding. For example, some hospitals have developed commercial arrangements with private providers to co-locate private hospitals onsite in order to generate additional income. Other organisations may need to adopt a more political or adaptive stance to maintain their competitiveness (Hosking & Gardner 1996). For example, Baptist Community Services in New South Wales have taken on a research focus in the field of aged and community care by establishing a Clinical Chair in gerontological nursing and a research unit, thus enabling them to undertake research to improve clinical outcomes and clinical effectiveness. This divergence of an organisation from its primary function should be undertaken within the context of the overall organisation strategy and not simply as an ad hoc decision. In 1966, an American management writer, Chandler (cited in McLaughlin 1996, p 726), argued that ‘structure follows strategy’. What he meant was that organisational structure was influenced heavily by mission, objectives and goals of an organisation. Strategy will impact on numbers of management layers, levels of authority, communication and decision-making processes. Whether structure follows strategy has been the source of some debate (Viljoen & Dann 2003, p 334). Mintzberg (1994) argues that strategy formation can be ‘emergent’ in that it arises from within the structure; this is more of a participative or ‘committing’ process than the traditional top-down approach. Mintzberg (1994, p 108) states that strategies: Thus it would appear that structure may follow strategy in some contexts and precede it in others (Heracleous 2003, p 17, Viljoen & Dann 2003), and that strategy and structure are quite interdependent (Mintzberg et al 2003). Organisational structure is not the only factor impacting on strategic success. In fact some writers maintain that it is the least important feature (Hubbard 2004, p 253). See Chapter 8, for a discussion of other factions which are associated with successful change processes and implementation of organisational strategy. To be successful, health care organisations must be able to deal effectively and creatively with their increasingly uncertain operational scenario. Organisational strategy and design are key elements in the adaptive capacity of organisations and, indeed, their survival in highly competitive environments. The ability to anticipate and respond to significant shifts within the environment is critical to the success of the organisation. A variety of factors affecting the development of organisational strategy are summarised in Figure 12.1. (See also Chapter 4, particularly the section on ‘forces driving change within Australian health care’.) The impact, or potential impact, that they can exert on health care organisations can conceptually differentiate these. The general environment encompasses trends occurring in the community as a whole, and can be considered as having a more indirect — albeit important — impact on health care organisations. On the other hand, the health care environment takes in trends affecting health care more specifically and thus can be thought of as affecting health care organisations more directly. Clearly, in the dynamic environments in which organisations operate, a good understanding of both dimensions of an organisation’s external environment is essential to effective strategic planning. Both the general and health care environments are complex, multifaceted entities. To facilitate the analysis of these environments it is helpful to group the trends into a number of key areas. One model that describes key environmental trends influencing organisations is the STEP (social, technological, economic and political) model as described by Piggot (2000). This is a useful model that can be applied equally well to the analysis of the external and internal environment regardless of organisational size or setting/location. Table 12.1 presents a checklist of factors that can be usefully considered during a STEP analysis. Table 12.1 The STEP model for analysing key environmental trends influencing organizations Source: Adapted from Piggot CS 2000 Business planning for health care management (2nd ed). Buckingham Press, Philadelphia An example of a partial environmental analysis for the development of a new clinical service is presented in Case Study 12.1. CASE STUDY 12.1 ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW CLINICAL SERVICE Directing attention to the external environment emphasises the importance of adapting to change, ‘fitting’ the organisation to the broader context and understanding the ‘rules of success’ that are written outside organisations (Ginter et al 2002, p 139). However, these elements are only part of an effective strategic planning process. What is also needed is an understanding of the organisation’s capacity, resources and capabilities and how these contribute to the development of organisational strengths and/or weaknesses. The internal environment encompasses all of the factors working within an organisation that can influence its operational effectiveness and/or efficiency and/or its competitive advantage. Organisations have certain strengths that enhance their ability to carry out their tasks. Conversely, they also have certain weaknesses that can limit their capacity to function optimally. Thus a thorough understanding of an organisation’s internal environment is essential to the development of effective organisational strategy and structure. Just as the external environment of an organisation is a complex, multifaceted entity, so too is the internal environment. One model that can be used to facilitate analysis of an organisation’s internal environment is the SSIFT (synergy, staff, information, financial, technical/physical) model adapted from Piggot (2000) and Ginter et al (1998). Table 2 presents a checklist of factors that can usefully be considered during a SSIFT analysis. Table 12.2 Analysis of an organisation’s internal environment Source: Derived from Ginter PM, Swayne LM, Duncan WJ 1998 Strategic management of health care organisations (3rd ed). Blackwell Business, Malden, MA; and Piggot CS 2000 Business planning for health care management (2nd ed). Buckingham Press, Philadelphia As part of the environmental analysis (internal and external), it is useful to analyse the influence of various stakeholders associated with the organisation in some way. These are people and groups who have an interest in the organisation, its outcomes and success or who are affected in some way by its activities. These individuals or groups have varying levels of power and influence on the organisation’s activities and overall direction. (For more information see Chapter 4 Organisational change and adaptation in health care.) Ginter et al (2002) also emphasise the importance of analysing competitors and how organisations establish their competitive advantage through the value that they create for their patients and stakeholders. Their adaptation of Porter’s Value Chain (Ginter et al 2002, p 141) combines evaluation of the usual support activities (culture, structure and resources), with evaluation of service delivery, including aspects of marketing. People working in private-for-profit health organisations may also wish to consider additional frameworks such as Porter’s Value Chain, Porter’s Five Competitive Forces, Porter’s Diamond Model, or a framework for analysing competition at an international level (see Porter 1998). These well-known models are discussed in most contemporary strategic management books; for example, Hubbard (2004), Viljoen and Dann (2003), Hitt et al (2005), Ginter et al (2002). Hubbard (2004) has even extended Porter’s five forces to an eight forces model. New means of evaluating strategic performance are also discussed more fully in the general strategy books. These extend beyond the traditional economic and financial measures to include social/community and environmental factors, other stakeholders such as customers and staff, the level of learning and innovation; for example, Triple Bottom Line and Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan & Norton 1996) (see also Hubbard 2004). The mission statement is often accompanied by a vision statement, or statement of strategic intent, that describes more broadly what/where the organisation wants to be when the purpose is being accomplished; that is, ‘Where do we want to go?’ ‘What do we want to be?’. The vision statement is usually short, specific to the organisation, and designed to motivate staff towards the achievement of a desired but realistic future state (Hitt et al 2005, p 386, Hubbard 2004, p 69). Vision and mission statements are often combined. Where they are not combined, the mission statement usually focuses on what the organisation is doing to achieve the vision; that is, it operationalises the vision (Hubbard 2004, p 69). Mission statements have become progressively more important in the administration of modern health care organisations. The principal reason for this is the complex and dynamic environment in which health care organisations find themselves operating. Changing mandates, reduced budgets and increased accountability are likely to provide continuing challenges in both the for-profit and not-for-profit health care sectors. Responding effectively to these challenges requires, among other things, the re-examination of organisational strategy. The development of a meaningful mission statement is a strategic exercise that is considered by academics and administrators alike as critical to the success of health care organisations (Bart 2000). An effective mission statement can be said to fulfil three main purposes: Despite some ongoing debate about the pragmatic or ‘real’ value of mission statements and their influence on organisational processes, there is now a substantial body of supportive literature and a number of studies have demonstrated a relationship between mission statements and organisational performance (Ginter et al 2002). For example, Bart (1997) found that the inclusion of particular content items in mission statements had a greater influence on employee behaviour than when they were not included; for example, ‘purpose’, ‘general corporate goals’, ‘self-concept’, ‘desired public image’, ‘values’, ‘concern for customers’ and ‘concern for employees’. While there are many ways of writing a mission statement, several key features have been identified as generally applicable to the mission statement of any organisation (Ginter et al 2002). However, mission statements do not need to include all of these. An overall summary of the features is presented in Table 12.3. Table 12.3 Key features of a mission statement Source: Derived from Ginter PM, Swayne LM, Duncan WJ 2002 Strategic management of health care organisations (4th ed). Blackwell Business, Malden, MA, pp 183–4 It might be useful at this point to consider some examples of mission statements (Box 12.1). Note that although the elements summarised in Table 12.3 are exhibited to a greater or lesser degree in the examples provided in Box 12.1, each mission statement attempts to capture the uniqueness of the respective organisation in terms of its reason for being. In this way these statements provide useful guidelines to staff and customers as to what the organisation should be doing. BOX 12.1 EXAMPLES OF ORGANISATIONAL MISSION STATEMENTS Source: Fleming M 2001 Annual Report. Nunyara Nursing Home, Fleming Group, Brisbane. Reproduced with permission

Describe theories and concepts underpinning current approaches to strategic planning and organisational design.

Describe theories and concepts underpinning current approaches to strategic planning and organisational design.

Discuss factors influencing organisational strategy and design, in particular environmental factors, mission and objectives, and organisational culture.

Discuss factors influencing organisational strategy and design, in particular environmental factors, mission and objectives, and organisational culture.

Analyse traditional and emerging organisational designs, in particular the functional, divisional, network and hybrids of the above, and matrix designs in terms of their relevance, strengths and shortcomings.

Analyse traditional and emerging organisational designs, in particular the functional, divisional, network and hybrids of the above, and matrix designs in terms of their relevance, strengths and shortcomings.

INTRODUCTION

THEORIES AND CONCEPTS UNDERPINNING CURRENT PRACTICE IN STRATEGIC PLANNING AND ORGANISATIONAL DESIGN

Primary function of organisations

Productive organisations: these organisations are interested in producing goods and services, making profits and creating wealth. Examples include financial institutions and large manufacturers.

Productive organisations: these organisations are interested in producing goods and services, making profits and creating wealth. Examples include financial institutions and large manufacturers.

Maintenance organisations: these organisations are committed to social, health and wellbeing goals. Examples include religious institutions, a number of non-government organisations, and health and community services.

Maintenance organisations: these organisations are committed to social, health and wellbeing goals. Examples include religious institutions, a number of non-government organisations, and health and community services.

Adaptive organisations: these organisations are oriented to knowledge creation and research. Examples include universities, research and development agencies, artistic and cultural groups.

Adaptive organisations: these organisations are oriented to knowledge creation and research. Examples include universities, research and development agencies, artistic and cultural groups.

Political organisations: these organisations are concerned not so much with individuals per se but more with maintaining the structure, order and regulation of the whole society. Examples include governments, legal structures and interest/pressure groups.

Political organisations: these organisations are concerned not so much with individuals per se but more with maintaining the structure, order and regulation of the whole society. Examples include governments, legal structures and interest/pressure groups.

Organisational strategy

FACTORS INFLUENCING ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY AND DESIGN

Environmental factors

The external environment

EXTERNAL ANALYSIS

the demographic profile of their catchment area demonstrates an increasing proportion of older people;

the demographic profile of their catchment area demonstrates an increasing proportion of older people;

national and state data suggest that hospital use for musculoskeletal conditions increases with age;

national and state data suggest that hospital use for musculoskeletal conditions increases with age;

The internal environment

SYNERGY

STAFF

INFORMATION

FINANCIAL

TECHNICAL/PHYSICAL

Stakeholder analysis

Organisational mission and objectives

Purpose of mission statements

to create a balance between the competing interests of various stakeholders, for example the community, customers, staff (Klemm et al 1991).

to create a balance between the competing interests of various stakeholders, for example the community, customers, staff (Klemm et al 1991).

Key features of a mission statement

CUSTOMERS AND MARKETS

The particular kinds of patients or clients for whom services will be provided; for example, children of all ages.

PRINCIPAL SERVICES

The special services that will be provided; for example, comprehensive diagnostic and treatment services for adult patients, high quality supportive care for frail elderly clients.

GEOGRAPHIC AREA

The particular geographical area where the organisation will operate; for example, a defined scope of activity, such as rural facilities/services.

ORGANISATIONAL PHILOSOPHY/VALUES

Key philosophical beliefs and/or values of the organisation; for example, a commitment to holistic caring, enhancing quality of life for clients.

ORGANISATIONAL GOALS

Key goals that the organisation is working towards; for example to promote optimal health and wellbeing, to enhance quality of life for clients and their families.

ORGANISATIONAL SELF-CONCEPT

The distinct way that an organisation ‘sees’ itself; for example, a private, not-for-profit integrated health service, a caring community/family, partnership of high-quality health care providers.

PUBLIC IMAGE

The way that the organisation wishes to be perceived by the community in which it operates; for example, high-quality, cost-effective services, delivery of services in a manner that values and respects the personal dignity and uniqueness of all who are served.

Example of a mission statement from a residential care setting

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Strategy and organisational design in health care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access