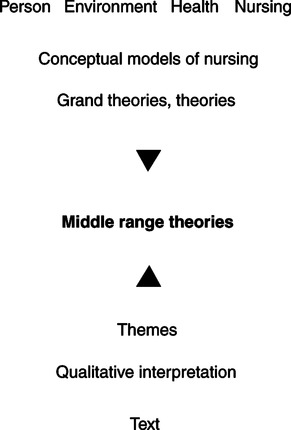

From studying this text, it becomes obvious that nursing theoretical works are active and growing as they point the way to new knowledge through research, education, administration, and practice applications. Each successive edition goes through reviews by the publisher in addition to published reviews that are given careful consideration in the production of new editions (Burns, 1999; Malinski, 1999; Paley, 2006; Reed, 1999). In this seventh edition, you will find updates of the chapters and the addition of a new theory chapter (Meleis’s Transitions in Chapter 20). Middle range theories continue to be a very important unit as more nurses recognize their utility and applicability in nursing practice (Sieloff & Frey, 2007; Peterson & Bredow, 2008; Smith & Liehr, 2008). As Burns (1999) noted, middle range theory fosters “theoretic thought and the growing recognition of the potential impact of theory on nursing practice” (p. 263). The references and bibliography are consistently noted as a major strength of the text. As Malinski (1999) observed, “they provide a valuable resource for students” (p. 265). The chapters are updated in this seventh edition, as in previous editions, with literature written by those using the various theoretical works in their professional practice and research. More and more nurses are recognizing that the theoretical works are vital for them to know, apply and guide practice, research, education, and administration (Alligood & Marriner Tomey, 1997, 2002, 2006; Alligood 2004; 2006c; 2010, in press). In the sixth edition, to deal with the growing body of nursing theoretical works and not eliminate those in earlier editions, a chapter was created to chronicle their historical significance. In this seventh edition, the work of Orlando has been added to this chapter (see Chapter 5). Reed (1999) observed in her review that “the book supports the momentum building within nursing to transcend the tired debate about the relevance of nursing models and apply this field of knowledge as a basis for understanding the substance and scholarship of nursing” (p. 268). In this seventh edition, the goal is to clarify the relevance of nursing theoretical works, facilitate their recognition as systematic presentations of nursing substance, and stimulate their use as frameworks for nursing scholarship in practice, research, education, and administration. The theoretical works developed within a discipline determine the nature of the questions asked, the research methods used to answer questions, and the scope of knowledge the questions address. Simply put, the framing of an issue determines the outcome. How might we as nurses explore the state of the art and science of nursing theory? That question is answered in the nursing literature that documents the use of nursing theoretical works around the world. This chapter presents the growth of nursing theory from three perspectives. First, the impact of the shift in philosophy of science on the development of theoretical works, changes that have informed qualitative approaches and quantitative methods (Carper, 1978; Kuhn, 1962, 1970). Second, nursing theory is viewed in the context of its new growth in this postmodern period that encourages reframing knowledge in present day understanding. Morris (2000) suggests, “the postmodern era often co-opts or revises rather than reject outright the achievements of modernism…” (p. 8). Finally, and third, the global nature of development and the use of nursing theoretical works call attention to the growing communities of scholars, highlight significant growth in theoretical organizations, and remind the reader of the transient but vital nature of theory for the profession, discipline, and science. Many nursing models and theories included in this text have developed such that they now exhibit characteristics of Kuhn’s (1970) criteria for normal science (Wood & Alligood, 2006). Increasingly, over the past 30 years, the conceptual models of nursing and nursing theories as presented by Alligood and Marriner Tomey (1997, 2002, 2006), Fawcett (1984a, 1989, 1993, 1995, 2000, 2005), Fitzpatrick and Whall (1984, 1989, 1996), George (1985, 1986, 1989, 1995, 2002), Marriner Tomey (1986, 1989, 1994), Marriner Tomey and Alligood (1998, 2002, 2006), McEwen and Wills (2002, 2006), Meleis (1985, 1991, 1997, 2005, 2007), and Parker (2001, 2006) have led to theory-based education, administration, research, and practice. Communities of scholars continue to grow, become more formally organized, address deeper questions, and share knowledge from their research and practice in newsletters and journals. Nursing models and theories provide nurses with perspectives of the central concepts of the discipline: person, environment, health, and nursing, the metaparadigm of nursing as set forth by Fawcett (1984b); concepts with wide acceptance as discipline boundaries are often noted without an author reference. The theoretical works generate scholarship as frameworks for research and theory-based nursing practice. Work within the communities of scholars around the nursing models has led to research instruments unique to that paradigm. Kuhn (1970) stated, “paradigms gain their status by being more successful than their competitors in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners have come to recognize as acute” (p. 23). Kuhn (1970) defines normal science as “research firmly based upon one or more past scientific achievements, achievements that some particular scientific community acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice” (p. 10). The characteristics of paradigms that evidence their nature and lead to normal science include: Rodgers (2005) describes normal science as “… the highly cumulative process of puzzle solving in which the paradigm guides scientific activity and the paradigm is, in turn, articulated and expanded” (p. 100). Rodgers (2005) cites Kuhn’s premise that research in normal science “is directed to the articulation of those phenomena and theories that the paradigm supplies” (p. 100). The conceptual models of nursing in this text exhibit these characteristics. Each model is unique and has ranges of development in these characteristics. Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings (see Chapter 13) is an excellent example, having generated hundreds of research studies, 13 research instruments, and 12 nursing process clinical tools for practice (Fawcett, 2005; Fawcett & Alligood, 2001). The Society of Rogerian Scholars, founded in 1988, publishes a refereed journal, Visions: The Journal of Rogerian Nursing Science, which facilitates communication and fosters development of the science among the community of scholars. Rogerian science is the basis of award winning texts and is used to structure curricula for undergraduate and graduate nursing programs (Fawcett, 2005). In 2008, at the Society of Rogerian Scholars fall conference at Case Western University, they celebrated twenty-five years of Rogerian conferences, the twentieth anniversary of the society, and fifteen years of the journal. Other conceptual models of nursing, such as Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Theory (see Chapter 14), the Neuman Systems Model (see Chapter 16), and Roy’s Adaptation Model (see Chapter 17), have experienced similar growth. Examples of nursing theories that exhibit characteristics of normal science are Erickson, Tomlin, and Swain’s Theory of Modeling and Role-Modeling (see Chapter 25), Leininger’s Theory of Culture Care (see Chapter 22), Parse’s Theory of Human Becoming (see Chapter 24), and Margaret Newman’s Theory of Health as Expanding Consciousness (see Chapter 23). As these societies of nursing scholars grow, the volume of publications increases, and research and practice grow exponentially. Theoretical works provide ways to think about nursing. Johnson and Webber (2001, 2004) addressed the future of nursing in questions about the importance of theory development for recognition of nursing as a profession, as a discipline, and as a science. They identify three significant areas affected by nursing knowledge and dependent on its continued development. Although theory affects recognition of nursing as a profession, a discipline, and a science, the future existence of nursing depends on use of substantive nursing knowledge not only for recognition, but also, to improve the quality of care to the patients whom we serve. Moving the practice of nursing to a professional delivery model requires transposing from the vocational style that many nurses have been taught and to which many cling to a professional style of delivery. This requires a systematic presentation of nursing. As knowledge is transferred to those coming into the profession, it is also done so with a style of practice. Substance is the requirement in any field of learning to be recognized as a discipline in academe. Although there are different views about nursing knowledge development, as nurses shift to a professional style of nursing, they move beyond “the tired debate about the relevance of nursing models and apply this field of knowledge as a basis for understanding the substance and scholarship of nursing” (Reed, 1999, p. 268). Most agree that “nursing knowledge arises from inquiry and guides practice” (Parse, 2008, p. 101). Nursing eagerly embraced qualitative research approaches to explore questions that quantitative research methods could not answer, and this expanded philosophy of nursing science resulted in qualitative theory development and many new middle range theories (Alligood, 2002; Alligood & May, 2000; Liehr & Smith, 1999; Peterson & Bredow, 2008; Sieloff & Frey, 2007; Smith & Liehr, 2003, 2008; Thorne, Kirkham, & MacDonald-Emes, 1997; Thorne, Kirkham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2004). These new theories expand the volume that continues to be developed with conceptual models of nursing and nursing theories as middle range or practice theory applications noted in these few examples: Orem (Biggs, 2008), Neuman (Casalenuovo, 2002; Gigliotti, 2003), Roy (DeSanto-Madeya, 2007; Dunn, 2005; Hamilton & Bowers, 2007), Rogers (Kim, Kim, Park, Park, & Lee, 2008), Newman (Pharris & Endo, 2007), King (Sieloff & Frey, 2007), and Parse (Wang, 2008). There is also a wealth of knowledge in early nursing theoretical writings (Alligood, 2002; Alligood & Fawcett, 1999; 2004; Butcher, 1999, 2002) that are rich resources for discovery of new theory, such as empathy in King’s Interacting Systems Framework (Alligood & May, 2000). Middle range theory is “the least abstract set of related concepts that propose a truth specific to the details of nursing practice” (Alligood & Marriner Tomey, 2006, p. 522). Expansive growth has occurred with nursing texts exclusively devoted to the presentation of middle range theories (Peterson & Bredow 2008; Sieloff & Frey, 2007; Smith & Liehr, 2003, 2008). This development is especially exciting as it closes the gap between research and practice (Alligood, 2006b). Liehr and Smith (1999) explored the nature of middle range theories in the nursing literature from 1988 to 1998 and identified 24 middle range theories. They noted that theory-generating approaches used in the 24 middle range theories were both quantitative and qualitative methods. Smith and Liehr (2003, 2008) subsequently published their method of middle range theory development and selected theories. Sieloff and Frey (2007) is middle range theory using King’s conceptual system. Other middle range theories are developed exploring aspects of people’s lived experiences to understand the meaning of life events. Application of middle range theories in nursing practice is encouraged for improving nursing practice quality, whether developed quantitatively or qualitatively. Both approaches are at the level of practice and develop useful nursing knowledge. Consideration of development of middle range theory in relation to a generic structure of knowledge reveals that theory from the hypotheticaldeductive method and theory from qualitative approaches arrive at a similar level of abstraction. In spite of the fact of their different philosophical basis and different methods and approaches, they produce knowledge at a similar level of abstraction (Figure 37-1).

State of the Art and Science of Nursing Theory

NATURE OF NORMAL SCIENCE

A community of scholars who base their research and practice on the paradigm

A community of scholars who base their research and practice on the paradigm

The formation of specialized journals

The formation of specialized journals

The foundation of specialists’ societies

The foundation of specialists’ societies

EXPANSION OF THEORY DEVELOPMENT

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access