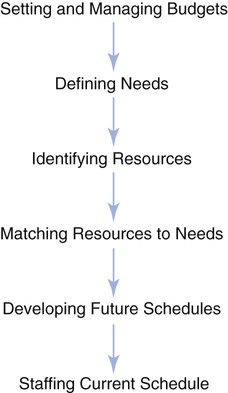

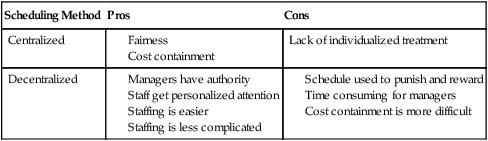

1. Discuss the determination of staffing needs. 2. Review the different types of assignment systems. 3. Identify the difference between centralized and decentralized staffing. 4. Differentiate between the various types of staffing patterns. 5. Discuss activities used by the nurse manager to support fluctuating staffing needs. One of the most time-consuming concerns of most nurse managers is the staffing of the unit. Staffing requires having enough staff to deliver care but also requires that the staff that are present are qualified to deliver the care. Staffing schedules are also a major concern of nurses as they enter a health care environment, and issues with schedules are often cited as a major job dissatisfier by nurses leaving the workplace (Halm, Peterson, & Kandelis, 2005). There have been multiple studies in the recent literature supporting the importance of safe staffing and its relation to patient safety (Hugonnet, Chevrolet, & Pittet, 2007; Stone, Mooney-Kane, & Larsen, 2007; Weissman, Rothschild, & Bendavid, 2007). Higher numbers of hours of nursing care provided by registered nurses and a greater number of hours of care by registered nurses per day are associated with better care for hospitalized patients (Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, & Zelevinsky, 2002; Needleman, Buerhaus, Stewart, Zelevinsky, & Mattke, 2006). In 1999, the American Nurses Association (ANA) published Principles for Nurse Staffing, which emphasized the nursing work environment to provide safe patient care (Box 19-1). The ANA’s Principles for Nurse Staffing (1999) offers standards to incorporate and balance the needs of patients, nurses, and organizations committed to positive patient outcomes. The principles recognize that providing nursing care services can be multivariate and complex. Subsequently, the ANA advocated a work environment that supports nurses in providing the best possible patient care by budgeting enough positions, administrative support, good nurse-physician relations, career advancement options, work flexibility, and personal choice in scheduling (ANA, 1999). Scheduling refers to making work assignments for the next work period. It is done from 4 to 8 weeks in advance depending on the institution (see Figure 19-1). The process of daily staffing begins with an assessment of the current staffing situation. The assessment includes the qualifications and competence of the staff needed and available (ANA, 2004). The next step is to formulate a plan to meet future needs. The staffing process culminates with a schedule (organized plan) of personnel to provide patient care services. Scheduling variables are defined as (Jones, 2007, p. 280): 1. The number of patients, complexity of patients’ condition, and nursing care required 2. The physical environment in which nursing care is to be provided 3. The nursing staff members’ competency levels, qualifications, skill range, knowledge or ability, and experience level 4. The level of supervision required 5. Availability of nursing staff members for the assignment of responsibilities There are various types of staffing systems in place in health care. The four major types are: 1. Centralized scheduling—Decision making occurs in a “centralized” location for the entire institution. 2. Decentralized scheduling—Decision making occurs with the nurse manager on the unit. 3. Mixed scheduling—Blends aspects of items 1 and 2. Individual units may manage staffing, but if they cannot fill open shifts, they might forward their needs to a centralized office. 4. Self-scheduling—Individual staff members schedule themselves. The nurse manager then works with staff members to fill empty slots. Many organizations are moving toward computer-assisted staffing. When managers are given authority and assume responsibility, they can staff their own units through decentralized scheduling (Tomey, 2004, p. 388). Scheduling staff, which is very time consuming, takes managers away from other duties or forces them to do the scheduling while off duty. Decentralized scheduling may use resources less effectively and consequently make cost containment more difficult (Tomey, 2004, p. 389). Table 19-1 provides pros and cons of centralized and decentralized scheduling. Table 19-1 PROS AND CONS OF CENTRALIZED AND DECENTRALIZED SCHEDULING • Pattern scheduling—Staff commit to work a set number of shift types in a given time frame. At the end of the time period, the pattern repeats (such as 3 weeks of day shift followed by 1 week of night shift, repeated every 4 weeks). Pattern scheduling can also include permanent shifts, block shifts, and rotating shifts (Box 19-2).

Staffing and Scheduling

STAFFING

THE AMERICAN NURSES ASSOCIATION PRINCIPLES FOR NURSE STAFFING

PROCESS OF STAFFING

PROCESS OF DAILY STAFFING

STAFFING AND SCHEDULING SYSTEMS

Decentralized Scheduling

Self-Scheduling

Scheduling Method

Pros

Cons

Centralized

Lack of individualized treatment

Decentralized

Staffing and Scheduling

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access