CHAPTER 3 Spirituality and the nurse: engaging in human suffering, hope and meaning

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to:

INTRODUCTION

‘Spirituality’ is a word laden with mystery that is a source of both comfort and uncertainty. It can not be touched or tasted, defies attempts at ‘pinning it down’, as in a laboratory, yet it flows out to connect every part of life. This ambiguity in understanding spirituality has led many to use metaphors: pictures to aid understanding. However, this only aids the inquirer so far. It is, after all, a mystery and you, the reader, are invited to contemplate. For nurses, it is contemplation vital to the health and wellbeing of those for whom they facilitate care. To use a metaphor, the discovery of spirituality is a journey each nurse will take, whether conscious of it or not.

SPIRITUALITY: AN ESSENTIAL EXPRESSION OF HUMANITY

TOWARDS A FLUID DEFINITION OF SPIRITUALITY: PLAYING WITH WATER

Spirituality is becoming an important topic of discussion in society in general and healthcare specifically. There are many studies attempting to measure spiritual values and beliefs as well as what can be described as assessment tools and strategies (McSherry & Ross, 2002). These often aim at determining if a person is experiencing spiritual distress. Fundamental to all this activity is how spirituality is defined and what constructs or concepts underpin the discussion.

The task of defining spirituality has been both contentious and difficult due to its subjective nature (Bash, 2004; Chung et al, 2007; McSherry & Ross, 2002). However, it is important for those in healthcare to take up the challenge. When reading on the topic of spirituality keep in mind the spiritual perspectives of the writer or researcher, as well as you, the reader. Each of these perspectives is of central importance. Burkhardt & Nagai-Jacobson (2002) state that ‘… spirituality is a phenomenon that is understood differently depending on the perspective from which it is viewed’ (p. 5). This variance in perspective, discussed above, is influenced by many interconnected aspects of human life. These include culture, religious background, socio-economic status, gender and sexuality. For example, atheists may express spirituality in terms that exclude religion or religious process, while secular humanists may deny the existence of spirituality as a valid element of human experience (McSherry & Ross, 2002). Whatever the perspective, defining spirituality is a complex and ongoing adventure.

With the above in mind, a simple starting point for this chapter is given by Chung Wong and Chan (2007) as ‘… the relationship with the self and a dimension beyond the self’ (p. 158). In this definition, the two dimensions often associated with spirituality can be seen: the relationship which the individual has with the self, an internal relationship; and that which the person has with an ‘other’. ‘Other’ is a term often used to describe either a divine being, such as a god, or another person. Religious world views are often called upon by individuals in defining how these two relationships are engaged and the extent to which they are experienced. For some, one relationship is internal, the relationship with the self, while the other is external, that is to say, the relationship one has with God. Other religious traditions perceive both of these as internal relationships: God is within. Whatever approach is taken, including the denial of an external being, every human being faces these two relationships at some level and at some point of time in their lives.

The essence of spirituality appears to be deeply integrated with how people derive and live out meaning in and of life. This includes how the individual defines their ‘world view’. By this it is meant that information is gathered from the world around them and, through multiple ‘filters’ such as familial, social, cultural, religious and personal experiences. It is difficult to express this process as a simple concept as it is dynamic and multifactorial (Neff, 2006). As this chapter will discuss, spirituality is a common human experience that sits above and behind personal religious belief and practice (Pesut, 2002). Swinton and Narayanasamy (2002) argue that spirituality is a universally experienced human phenomenon that is intensely subjective. It is this very subjectivity that underpins the imperative for nurses to act with the deepest respect towards those for whom they care. Inherent in this is a fragility of mystery from which human meaning and spiritual world views are constructed. The bridges over which the self travels in the process of relating to others and the divine are unique. Spirituality is the process of forming the bridge.

SPIRITUALITY AS CONNECTION

‘Transcendence’ is a term often applied to the role of spirituality in connecting the self to another. This connecting serves to enrich and derive meaning from the relationships that the self touches. In this reaching and touching, relationship is formed and is core to both the human process of relating and caring in nursing (Chang, 2001). The simple touch of compassion towards a person in need can be the source of immense meaning for both the giver and the receiver (Mok & Chiu, 2004). It is in the connection and the intention of the connection that relationship forms. Both receive as they move beyond themselves and experience ‘otherness’. Paradoxically, the otherness is then brought deeply within the self and their sense of self is enriched. The same can be said for negative connection such as abuse. Think of the impact of domestic violence on the victim: diminished sense of self and impaired ability to re-connect meaningfully.

THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN SPIRITUALITY

Religion and spirituality are often confused with each other, religion being considered equal, conceptually, to spirituality. This is due largely to post-World War II social change and the challenge of the traditional role religion held in the western life (Bash, 2004). With the influx of eastern spiritual traditions into the West, spirituality has been defined in new ways (Bash, 2004). However, it has not been a clean process due to the rise of diverse religious belief systems. This upheaval in thought has introduced an understandable yet unhelpful confusion to a consideration of the complexities of spirituality.

At one time, being religious and being spiritual were synonymous, as evidenced by the lack of equivalent term to ‘spirituality’ in the Judeo–Christian religious tradition (Bash, 2004). However, it could be argued that if a person needed to be religious in order to be authentically spiritual, the experiences of many people, including scientists, healthcare professionals, artists, poets, musicians and philosophers, would mean little. Regarding the place of religion, and science in life, Albert Einstein once said, ‘Science without religion is lame, but religion without science is blind’ (O’Connell & Skevington, 2005).

As discussed earlier, spirituality involves the ‘stuff’ of life. This does not mean religion does not play an important role in the process of life. Neither does it mean that the person is required to be engaged in a recognised religion (Taylor, 2002). Rather, religion provides a structure for spiritual expression. Religious beliefs may help the individual to construct a view of the world and thereby derive meaning for living their lives (Taylor, 2002). The practice of the religion, then, assists in the reinforcing of those views.

Some religions are theistic, meaning they hold a central belief in the existence of a god or gods. They also may dictate the behaviour of their members regarding world views, moral values, practice and worship. The Judeo–Christian tradition has a long yet varied history representing two theistic branches of monotheism. Another monotheistic religion, Islam, holds similar beliefs about the value of life and the need for caring for the sick as an extension of belief in God (Rassool, 2000). Furthermore, many of the advances in medicine, science and mathematics prior to the western European Renaissance were due to the work of Islamic scholars (Rassool, 2000). Atheism, on the other hand, while it never describes itself as a religion, has similar albeit opposite beliefs to theism. Regardless of the paradigm, it is important to realise that spirituality flows beyond religious structures.

THE ROLE OF RITUAL IN SPIRITUALITY

Human beings are essentially ritualistic. While the term ‘ritual’ implies a religious practice, it is seen in broader terms as a human phenomenon. Including religious observances such as going to a sacred space such as a mosque, church or temple, human ritual extends to every part of human existence. Rights of passage in life, such as what we do to connect with another person (for instance common greetings such as the bow or handshake) and the marking of changes in intimate relationships (such as engagement or betrothal, marriage and death), express milestones in life. Other more mundane examples, such as how people choose their clothes, bathe and eat, as well as celebrate ‘special’ occasions such as birthdays and anniversaries, and mark grief and loss, speak of the ritual existence humans live. All these things connect with some sense of meaning in life and ways used to express that meaning. The expression of meaning through ritual can also facilitate gaining greater understanding itself. As such, ritual plays an important role in the lives of those living with chronic illness and/or disabilities and such experiences can bring significant challenge to their sense of self and world view.

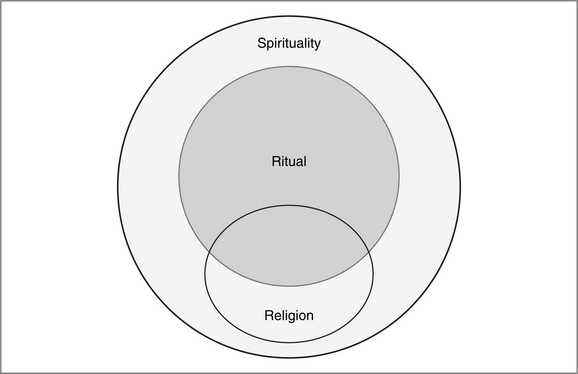

In summary, the concepts of spirituality, religion and ritual can inform and flow into each other. However, spirituality is the broader context for both religion and ritual, both of which form expressions of spirituality. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT

Human development is a complex process. Developmental psychologists such as Piaget and Erickson have contributed significantly to understanding this phenomenon. As this chapter has argued, the spiritual is indivisible from the physical and therefore undergoes a developmental process. There have been several attempts to posit theories of spiritual, faith or religious development (Streib, 2001; Taylor, 2002). The most significant of these has been Fowler’s Stages of Faith Development (Fowler, 1981; Taylor, 2002). This is a seven-stage model developed following analysis of 400 interviews and is briefly given below (Fowler, 1981). Please note that Fowler defines faith in broad universal terms; that is, the process of finding meaning in life rather than a religious structural definition (Fowler, 1981; Taylor, 2002).

Fowler’s approach is a linear model that has not been without its critics (Streib, 2001). Streib (2001) argues for a more dynamic and open theory. Herein lies a caution regarding linear models: they are limited in that they reduce the process to a series of statements to aid understanding. Whatever system is engaged, it is important to note that spiritual development is not a constant belief but a process of unfolding and becoming. Nowhere is this seen more than when a person is confronted with illness, particularly chronic illness. Here, the individual’s very world view is challenged and they must then traverse the paths to a new understanding and meaning.

THE MYSTERY OF SUFFERING: THE EFFECT OF CHRONIC ILLNESS

FINDING MEANING IN SUFFERING

Suffering is a recurrent theme in discussion relating to spirituality and health. Reed (2003) defines suffering as ‘… a syndrome of some duration, unique to the individual, involving a perceived relentless threat to one or more essential human values, creating certain initially ominous beliefs and a range of related feelings’ (p. 11). Cassell (1991), writing what has become a seminal work on the topic, defined suffering as ‘… the severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person’ (p. 33). Importantly, this notion of threat to ‘intactness’ or integrity of a person is not solely reliant on an event but also the perception of what that event means for the individual (Rowe, 2003). For you as the nurse, the ‘take home’ message found in these two definitions is this: the uniqueness of the person’s experience is paramount (Reed, 2003); and suffering has the power to alter an individual’s perception of meaning (Cassell, 1991; Rowe, 2003). Suffering confronts the established patterns of life, challenging the one suffering to struggle with finding new meaning. Reich (1989, cited in Taylor, 2002, p. 159) echoes this by saying suffering is ‘… a frustration to the concrete meaning that we have found in our personal existence’. The concrete nature of meaning exposes the fragility of human world views. Given a significant enough confrontation through an event or perceived consequence of an event, the constructed meaning can crumble. This crumbling is suffering!

Reed (2003) gives four themes related to suffering, including isolation, hopelessness, vulnerability and loss. Isolation is a common experience in suffering (Reed, 2003) and includes the alienation people feel when faced with difficulty in sharing their experiences (Rehnsfeldt & Eriksson, 2004). It can also come about through disruption in normal caring patterns: being cared for and caring for others (Reed, 2003). Hopelessness, experienced as despair or the belief that they are without hope, is a significant experience of those who suffer (Reed, 2003). However, it is important to note that the extent to which people experience hopelessness varies with the individual and circumstances, such as in chronic illness, where the feeling may be transitory (Farran et al, 1995).

The conflict that chronic illness can engender in a person’s life means that ways must be found to make meaning out of the circumstances and consequences to the self. Kralik (2002) describes this as a process of transition that the women in her study experienced from the ordinariness of their perceived world into the turmoil of chronic illness. One study participant said:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree