Chapter 39 Special issues regarding women with HIV infection

Nature of the HIV Epidemic Among Women

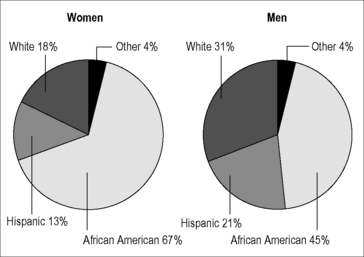

Globally, about half the cases of HIV infection (or roughly 16.8 million) occur in women and girls, with the majority (12 million) occurring in females in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Indeed, a recent report released by the World Health Organization lists the most common cause of death and disability in women of reproductive age worldwide to be HIV/AIDS [2]. Although HIV infection among women is not as common in the developed world, rates have increased in this group over the last 30 years. Currently, the number of cases of HIV infection among women in developed countries is comparable to those of many other chronic diseases. As of the last UNAIDS global update on the epidemic in 2009, 240,000 women were reported to be living with HIV in Western and Central Europe and 390,000 in North America [1]. In the USA, as reported in the 2009 surveillance report, 75% of HIV cases were in males and 25% in females [3]. The number of cases among males increased 10% between 2005 and 2008, but case numbers among women remained flat; these data contrast with expectations that the number of recognized HIV infections among US women would substantially increase if testing became more routine. Regardless of the sex ratio, the average rate of HIV infections among US women is currently 179 cases per 100,000 women, with some states reporting rates up to 460 per 100,000. Racial disparities in rates of HIV infection among US women are prominent: although only 14% of US women are African American [4], this group comprises 67% of all cases. Figure 39.1 shows the percentages of HIV/AIDS cases in US women by race/ethnicity compared to those in US men as of the latest CDC surveillance report [3]. Although HIV/AIDS does affect racial and ethnic minorities disproportionally in men as well, this disparity is even more stark among US women.

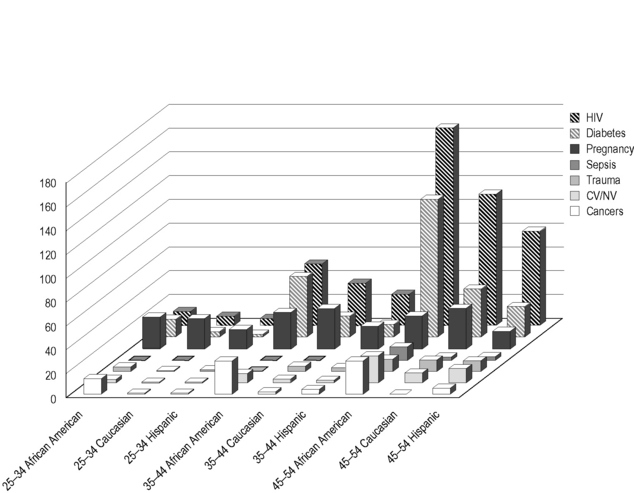

AIDS is among the 10 most frequently reported causes of death among African American and Hispanic adolescent and adult women (Fig. 39.2) [5]; this figure is likely to underestimate the contribution of HIV to mortality among these groups because it is limited to cases in which HIV infection was recognized, and only includes cases in which AIDS was reported to be a cause of death. Not only is HIV infection more common among African American women at all age ranges but also rates of death in this community from HIV/AIDS are disproportionately higher than mortality rates from the infection in other groups of American women. Moreover, although the most common causes of death at all ranges are malignancy and cardiovascular disease or strokes, undiagnosed HIV infection could contribute to any of these causes of death. Indeed, HIV infection, even when treated, is associated with excess deaths due to cancer, pneumonia, cardiovascular and neurovascular disease, diabetes, liver disease, and renal dysfunction. Therefore, HIV, whether undiagnosed or treated, could contribute to excess death and to morbidity in minority women that may not be registered in mortality statistics. Even when treated, the contribution of HIV to other forms of chronic morbidity and to mortality is expected to only increase as HIV-infected individuals on combination antiretroviral therapies (cART) survive for longer periods of time. Women living with HIV infection, therefore, require careful clinical assessment and treatment, including special attention to these chronic conditions that result directly from HIV-mediated immune activation.

Transmission of HIV to Women

Most transmission of HIV to women occurs during sexual contact and sexual risk may coincide with risks from injection needle use, making the precise determination of the mode of transmission in women with dual risk factors difficult. Because exposure events are frequently not recognized (the presence of HIV infection in sexual or needle-sharing partners is frequently unknown), women with HIV infection may deny any known risk factor. For large populations, the predominance of heterosexual transmission is imputed, and likely to be correct. The key concept here is that risk factors for HIV acquisition are frequently not recognized among women, so that assessment of risk is not a sensitive or useful means of triggering testing in women. Routine screening for HIV infection in medical settings is now recommended for all individuals aged 13 to 64 years in the USA; this strategy is likely to be cost-effective [6] and may be of particular value to case identification in women.

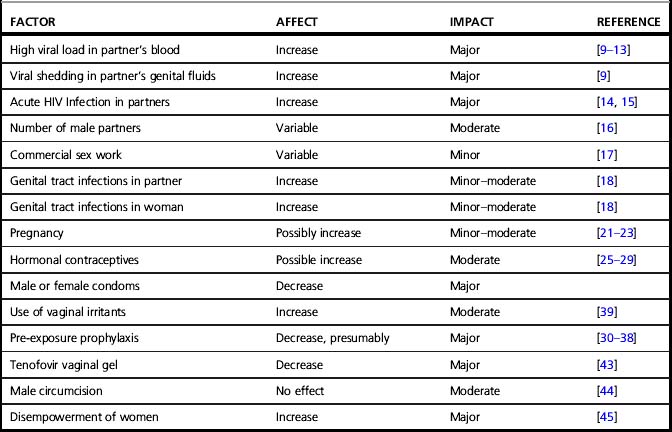

Transmission rates per heterosexual coital act are very low but likely to be highly variable within sexual pairs (discussed in Chapter 36) [7]. Estimates of the rates of transmission for single male-to-female sexual acts range from 0.02 to 0.43 depending on geographic location (rates are higher in low-income countries), and whether the sex was transactional (transmission rates are lower with commercial sex) [8]. Even though single sex acts confer minimal risk, sex is a common behavior, so the ongoing sexual transmission of HIV to women on a global basis has been sustained. Several factors are known to influence infectiousness or susceptibility to HIV infection, and other factors are biologically plausible but unproven. Table 39.1 summarizes the factors that may modify the susceptibility of women to HIV acquisition during heterosexual sex and further detail on how these factors influence risk is provided below:

• HIV viral load in partner: Greater HIV RNA copy numbers (viral load) in blood or genital secretions is an important predictor of infectivity from males to females [3]. Factors that reduce viremia, such as receipt of cART, are associated with decreases in HIV transmission [9]. Consistent use of cART on the population level should result in decreased HIV transmission rates [10, 11]. Indeed, the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 trial, terminated early due to positive results, showed that the risk of transmission from HIV-infected to HIV-uninfected partners is reduced by 96% with the early use of cART, regardless of CD4 cell count [12]. In individual couples, consistent use of cART may not completely eliminate transmission, but massively reduces the risk [13].

• Acute HIV infection: The period of time surrounding acquisition of new HIV infection is an important window of increased infectivity likely related to relatively uncontrolled viral replication with minimal host immune responses leading to high levels of viremia and genital shedding [14]. Non-specific symptoms of the acute seroconversion syndrome limit the efficacy of strategies that involve counseling individuals to avoid sexual contact with acutely infected persons. If the substantial challenge of improving the detection of cases of early HIV infection was paired with safer sex or treatment interventions, a significant reduction in the incidence of HIV infection could be achieved [15]. The risk of transmission is also heightened in late-stage untreated HIV infection when HIV viral loads rise.

• Number of sex partners: A larger number of male sexual partners is consistently associated with increased rates of infection [16], but infections are also commonplace in women with a single sexual partner.

• Commercial sex work: Exchanging sex for money, drugs or other items is associated with increased risk of HIV infection, though commercial sex workers in developing regions have demonstrated a lower per sexual contact risk than other women, perhaps due to greater use of condoms in this high-risk population over time [17].

• Genital tract infections: Genital infections have been found to be associated with HIV transmission in numerous studies [18]. The findings are based on studies of a wide variety of pathogens ranging from viruses to protozoans, and clinical manifestations including cervicitis/urethritis, vaginitis, genital warts, and ulcers. Each of the implicated diseases produces localized inflammation and/or immune activation, which could increase susceptibility to HIV. Genital ulcerative diseases are of particular import, having the most consistent association with an increased prevalence of HIV infection. Of these conditions, genital herpes is a key pathogen due to its high prevalence and recurrence rate. Another important pathogen implicated in the spread of HIV infection in developing world settings is Haemophilus ducreyi, the agent of chancroid, a bacterial infection that is prevalent in regions with high-intensity HIV epidemics. Genital ulcers result in loss of epidermal or mucosal barrier functions in addition to producing local inflammation, which may be a particularly potent combination in terms of augmenting HIV transmission. However, the extent of the interactions between sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV transmission is, for the most part, relatively modest, and intervention studies designed to control STDs as a means of preventing HIV infection have not been consistently successful [19, 20]. Regardless of the precise biological interaction between STDs and HIV, the occurrence of STDs is an indicator of the risk of HIV, and the prevalence of STDs in a given population is a good predictor of the intensity of the HIV epidemic in that setting.

• Pregnancy: Overall research findings indicate that pregnancy increases susceptibility to sexual HIV transmission [21, 22]; however, study results are not entirely consistent [23]. Findings from studies in sub-Saharan African women are most consistent, perhaps because the large number of transmission events supports adequate study power. Pregnancy could influence susceptibility to HIV infection in several ways, including increased fragility of genital tract tissues and alteration in host immunity during pregnancy, increasing the susceptibility to some infections. Incident infection with HIV during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of mother-to-child transmission [24] and may be missed if HIV testing is only performed in the first trimester. Therefore, the CDC routine testing guidelines recommend repeat HIV testing during the third trimester if risk factors are present or if the prevalence of HIV infection in the surrounding community is high. Finally, since acute infection with HIV late in pregnancy could be missed prior to delivery with an HIV antibody test alone, testing should be extended to the postpartum period in high-risk individuals.

• Hormonal contraceptives: Several studies have found that the use of hormonal contraceptives increases susceptibility to HIV infection [25, 26], but not all studies support this association [27, 29]. A variety of hormonal contraceptive formulations are commonly used, and the existing studies have often grouped them in assessing their effect on susceptibility to HIV. Since the specific sex steroid composition of these drugs may influence immunologic and genital tissue effects, mixing of formulations in studies may tend to obfuscate underlying associations. Current studies indicate that of the contraceptive sex steroids, depo medroxyprogesterone acetate (depo MPA) has the closest association with HIV transmission, but further study is needed to confirm this given the tremendous utility of this injectable contraceptive in resource-rich and resource-poor settings.

• Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the form of daily use of tenofovir/emtricitabine (TFV/FTC) has been recently demonstrated to reduce rates of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men (MSM)[30]. Two other recent studies (Partners-PrEP and the Botswana TDF2 HIV Prevention Study [31, 32]) demonstrated the efficacy of TFV/FTC as pre-exposure prophylaxis in both men and women in stable serodiscordant heterosexual couples. The FEM-PrEP trial, however, designed to assess the efficacy of TFV/FTC in high-risk African women for PrEP, was terminated early (on April 18, 2011) after interim analysis showed equal rates of infection in each group [33]. The ongoing VOICE study (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic) is a 5-arm placebo-controlled trial assessing the effectiveness and safety of daily oral TFV-based products or vaginal TFV gel in preventing HIV acquisition in African women. The five arms of the trial were originally established to compare daily oral TFV, oral TFV/FTC, vaginal 1% TFV gel to the appropriate placebo products in preventing HIV acquisition on women. On September 16, 2011, the TFV-only arm of VOICE was closed for futility, although the arm evaluating the efficacy of TFV/FTC is continuing. Although data are not yet available on the reasons for these disparate efficacy results for PrEP in MSM, heterosexual women in stable serodiscordant partnerships, and high-risk African women, postulated reasons include differences in adherence to study product, differences in trial designs in terms of the use of hormonal contraceptives, and differences in the degree of penetration of oral tenofovir into the rectal mucosa versus the vaginal mucosa (i.e. rectal penetration higher than vaginal). Ongoing data analyses of these trials and ongoing arms of PrEP trials in heterosexual women should further refine the utility, frequency, timing, route of administration, and specific populations who will benefit most from TFV-based prevention.

• Topical spermicides and genital preparations have been proposed as prevention interventions for HIV that would have special relevance for HIV-infected women. Nonoxynol-9, a commonly used detergent that serves as a spermicide, is virucidal in the test tube, but resulted in paradoxical increases in HIV transmission in humans [39]. Follow-up studies demonstrated that nonokynol-9 produced inflammation of the vaginal mucosa, a finding that may explain this apparent promotion of HIV transmission. Several other topic vaginal microbicides demonstrated no efficacy in preventing HIV transmission [40–42]. A recent trial demonstrated that vaginal application of 1% tenofovir gel twelve hours before and after each coital episode was effective in reducing the incidence of HIV infection among women in South Africa. The CAPRISA 004 trial found that vaginal 1% TFV gel reduced HIV infection rates by 39%, with a 54% reduction in “high adherers” (>80%) defined by self-report or applicator counts [43]. However, the vaginal 1% tenofovir gel arm of the VOICE trial was recently halted (on November 17, 2011) when the data safety and monitoring board concluded that the gel applied daily was ineffective in preventing HIV acquisition in VOICE trial participants. Ongoing studies of strategies to administer vaginal 1% TFV gel in women as an HIV prevention measure will hopefully clarify the utility of this product. Moreover, additional HIV-specific products formulated as microbicides to prevent HIV acquisition in women are currently under study.

• Male and female condom use is highly effective in the prevention of HIV transmission to and from women.

• Male circumcision: While male circumcision is highly effective in reducing the risk of sexual acquisition of HIV infection in men, it has little effect on transmission from an infected male to his female sexual partner [44]. However, population effects by which male circumcision will promote reduced prevalence of HIV infection among sexually active males will eventually lead to reduced exposure to the infection among female partners.

While biological factors are undoubtedly important determinates of HIV transmission in populations, additional characteristics likely influence the chances that an individual woman will acquire HIV infection, including many social factors that may determine whether she encounters an infected male partner and is capable of effectively engaging in risk-reduction behaviors. These social factors include income, education, employment, family size, mental health, cognitive function, and the presence of substance use. The social factors may produce vulnerabilities in individual women that are ultimately mediated through a loss of sexual autonomy [45].

The Natural History of HIV in Women

While the similarities in the course of HIV infection among women and men outnumber the differences [46, 47], the differences are important to understand. Women have higher rates of many autoimmune diseases than men, reflecting, in part, a pattern of more robust immune responses in females. Women also tend to respond more vigorously to vaccination and to clear some infections more frequently than men. Females have higher absolute CD4 cell counts than males (approximately 100 cells/mm3), a difference that is found across age and racial groups, and a difference that persists in HIV infection [48, 49].

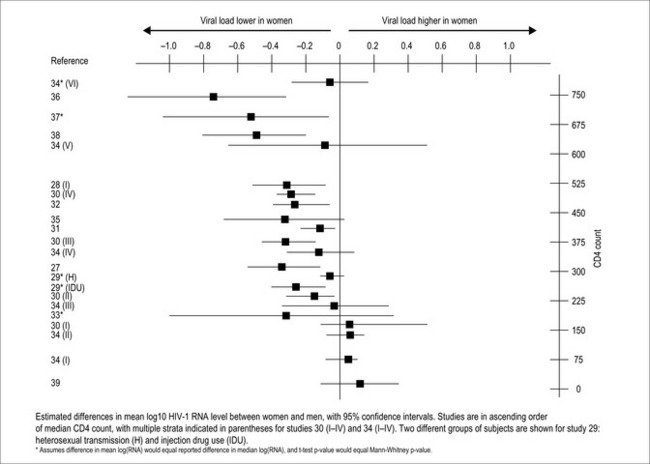

Women have viral loads approximately 0.2 to 0.8 log10 lower than men during early HIV infection, when CD4 cell counts are greater than 400 cells/mm3 (Fig. 39.3) [48, 50–63]. As CD4 cell counts decline, the sex discordancy in viral load lessens and disappears. Since viral load is predictive of the rate of disease progression, longer disease-free survival might be expected for women, but this has not been observed. Time to clinical progression is equal between the sexes, so women actually progress more rapidly to AIDS per a given viral load. Recent research has provided some clues to this seeming paradox. Women pay a price in heightened immune activation for their early control of viral replication, and this heightened immune activation may eventually lead to more rapid loss of CD4 cells [64]. Additionally, women produce more IL-7, a regulator of CD4 cell production, at a given CD4 cell count than men [49]. IL-7 also stimulates HIV replication, so the greater response to CD4 depletion that females demonstrate could also result in the generation of more HIV viral particles.

In the USA the chances of progression to clinical AIDS among HIV seroconverting women is heavily influenced by race and geographic location, with the highest rates of clinical AIDS occurring among African American and Southern women [48]. Women with HIV infection have lower blood hemoglobin and albumin levels, which are indicators of overall and non-AIDS-related survival, but women experience similar increases in these values to men after initiation of cART [65].

In terms of clinical progression rates of chronically infected individuals on therapy (see Antiretroviral Treatment of Women section), earlier studies showed that women seemed to have higher rates of progression to AIDS or death than men [66], likely due to differential access to care or ART, or increased rates of substance abuse. Later studies that correct for these factors show no differences in rates of progression by sex [67], with some more recent studies suggesting better clinical outcomes in women versus men when adjusting for other relevant factors [68]. Hypotheses around these sex disparities are presented below.

Clinical Manifestations of HIV in Women

Acute infection

A recent paper evaluated race and sex differences in outcomes of primary HIV infection in the Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP), a multicenter, observational cohort of more than 2,000 patients diagnosed with acute and recent HIV infection during the cART era [48]. At enrollment into AIEDRP, women averaged 0.40 log10 fewer copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA (p < 0.001) and 66 more CD4 cells (cells/mm3) (p = 0.006) than men, consistent with reports from chronically infected individuals [49, 50]. In terms of differences unrelated to biology, initiation of cART was less likely at any time point by nonwhite women and men compared to white men (p < 0.005). Sex (and race) did not affect responses to ART after 6 months on therapy, but women were 2.17-fold more likely than men to experience more than one HIV/AIDS-related event (p < 0.001). Therefore, despite more favorable clinical parameters initially, female HIV-1-seroconverters had worse outcomes than did male seroconverters and these differences were exacerbated in non-white individuals.

Cancer

In the cART era, HIV-infected men and women both continue to experience cancer rates that are on an average 3–4 times that of the general population, although one recent analysis of cancer cases among HIV patients in France indicates that peak age of the highest relative risk of cancer is lower among women than men (under 40 versus under 50 years) [69]. These data likely reflect the small number of cases of malignancy in older individuals; more precise estimates of the cancer rate in older groups of HIV-infected persons will become available with increasing survival rates due to treatment and subsequently larger populations of older HIV-infected adults. In a large study of cancer cases among HIV-infected individuals in Belgium, rates of non-AIDS-defining malignancies were comparable between men and women, but survival of the women, many of whom were immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa, was significantly shorter than for the men (an average of 14 versus 32 months) [70]. The section below on women-specific conditions discusses cancers (e.g. breast, cervical, anal) that are more likely to demonstrate disparities by sex.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is common among HIV-infected women. Clinicians should be aware that spontaneous clearance of this co-infection occurs more frequently among women than men [71]. Furthermore, women with HCV are less likely to be viremic and tend to have lower hepatic transaminase levels with higher platelet counts than men at similar stages of HCV infection [71, 72]. However, data on sex differences in HCV infection mainly exist for the mono-infected population and further studies on the impact of sex on HCV progression in HIV-infected individuals are indicated [73].

Body habitus and metabolic changes

Sex differences in the distribution of body fat in HIV-uninfected adults are quite evident, and these differences persist in HIV-infected men and women. However, although HIV-infected women have smaller amounts of subcutaneous fat and total body fat than uninfected women [74], both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women have higher measurements of body fat than men [75]. The decreases in body fat (most prominent in the limbs) associated with HIV infection are smaller among women than men [75]. HIV infection in women is associated with higher blood levels of triglycerides and insulin, as well as lower levels of HDL, than observed in HIV-uninfected women [76]. Menopause influences blood lipids and triglycerides, such that LDL and triglyceride levels increase after menopause in HIV-uninfected women [77]. Therefore, careful evaluation of lipids in HIV-infected women, with greater attention in the postmenopausal period, is warranted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree