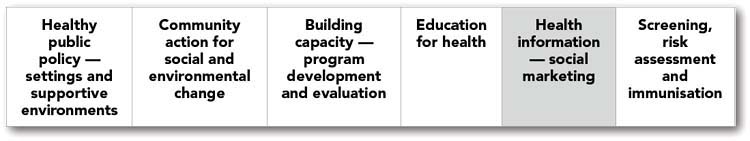

CHAPTER 8 Social marketing approaches to health promotion

In Chapter 8 we move further along the continuum of health promotion approaches outlined in Chapter 1 and examine some of the social marketing approaches to health promotion. The aim of social marketing strategies in health promotion is to change health behaviour. The strategies are often criticised because they focus on individual action and not necessarily the context of people’s lives, which may be a barrier to change. Social marketing approaches are useful when there are clear links between them and other approaches which are grounded in the social setting.

Social marketing can be defined as:

The principles of social justice, equity, community control and working for social changes that impact on health and wellbeing do not necessarily form the foundation of social marketing. The health promotion approaches at this end of the continuum have usually constituted selective Primary Health Care because they have concentrated on prevention of diseases and conditions based on epidemiological evidence, although more recently, social marketing strategies have been designed to take account of the broader environment and to address issues of social change.

SOCIAL MARKETING

As the term ‘social marketing’ suggests, a significant function, in addition to providing health information, is the ‘selling’ of a social idea; bringing about gradual social change. For example, the concept of ‘safe sex’ being everyone’s responsibility has widely permeated society following the initial publicity about the spread of HIV and AIDS. Previously, the topic of sexual behaviour was considered to be a personal and private matter, not discussed in public forums. See Insight 8.1 for a summary of a health promotion project with a social marketing focus. The ‘WayOut’ (Insight 8.1) project won a 2004 State Government of Victoria Public Health excellence award for innovation in the capacity-building category.

Social marketing campaigns typically involve an organised set of communication activities, such as:

Advertising: perhaps most notable as well-funded national campaigns about key social health issues, such as safe driving and smoking cessation. Campaigns conducted by the Transport Accident Commission (TAC), Land Transport New Zealand (LTNZ) and the Cancer Council — QUIT and SunSmart — have achieved prominence.

Advertising: perhaps most notable as well-funded national campaigns about key social health issues, such as safe driving and smoking cessation. Campaigns conducted by the Transport Accident Commission (TAC), Land Transport New Zealand (LTNZ) and the Cancer Council — QUIT and SunSmart — have achieved prominence.

Publicity materials: mass media campaigns that have a memorable logo or catchy slogan have promoted wide awareness. For example, the red tick of approval from the Heart Foundation for ‘heart safe’ foods (http://www.pickthetick.org.nz/TickProducts/products.fruitveges.html), or up until recently ‘Slip Slop Slap’ for sun protection — Cancer Council Australia (http://www.cancer.org.au/cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Campaignsandevents/SlipSlopSlap.htm).

Publicity materials: mass media campaigns that have a memorable logo or catchy slogan have promoted wide awareness. For example, the red tick of approval from the Heart Foundation for ‘heart safe’ foods (http://www.pickthetick.org.nz/TickProducts/products.fruitveges.html), or up until recently ‘Slip Slop Slap’ for sun protection — Cancer Council Australia (http://www.cancer.org.au/cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Campaignsandevents/SlipSlopSlap.htm).

Edutainment: this is an under-recognised role of the media in promoting or changing social awareness about various issues. Specific themes, such as respect for people suffering mental health problems, or the issue of domestic violence, and violence against women are crafted into television series and films. Health promotion professionals provide advice in script development. For an excellent example of the successful use of edutainment in social marketing see the comprehensive description of the Soul City multimedia edutainment program that was developed in South Africa in 1994 and has now run for eight series. Soul City is a dynamic and innovative multi-media health promotion and social change project. Through drama and entertainment Soul City reaches more than 16 million South Africans. ‘Through its multi-media and advocacy strategies the program aims to create an enabling environment empowering audiences to make healthy choices, both as individuals and as communities’ (Goldstein et al 2004; Soul City available at: http://www.soulcity.org.za/). Detailed evaluation of this program and the associated resources has demonstrated the effectiveness of the approach when the focus moves away from individual behaviour to interpersonal and social change (Scheepers et al 2004).

Edutainment: this is an under-recognised role of the media in promoting or changing social awareness about various issues. Specific themes, such as respect for people suffering mental health problems, or the issue of domestic violence, and violence against women are crafted into television series and films. Health promotion professionals provide advice in script development. For an excellent example of the successful use of edutainment in social marketing see the comprehensive description of the Soul City multimedia edutainment program that was developed in South Africa in 1994 and has now run for eight series. Soul City is a dynamic and innovative multi-media health promotion and social change project. Through drama and entertainment Soul City reaches more than 16 million South Africans. ‘Through its multi-media and advocacy strategies the program aims to create an enabling environment empowering audiences to make healthy choices, both as individuals and as communities’ (Goldstein et al 2004; Soul City available at: http://www.soulcity.org.za/). Detailed evaluation of this program and the associated resources has demonstrated the effectiveness of the approach when the focus moves away from individual behaviour to interpersonal and social change (Scheepers et al 2004).

Those who support social marketing in health promotion believe that it can contribute positively if it is part of an integrated health promotion program and if too much is not expected of it, given the context in which it is being used. Social marketing activities may be aimed at individuals, networks, organisations, manufacturers and planners and at societal levels. They are most effective when they are combined with interpersonal and community-based events to enhance health options. Media interventions alone, without complementary health education and community development approaches, are likely to have little impact on behaviour (Egger et al 2005). It is important to bear in mind that the advertising industry itself conducts considerable market research and targets its advertising very specifically to the groups it wishes to convince. Health workers at a

INSIGHT 8.1 WayOut: Rural Victorian Youth and Sexual Diversity Project

Below is an example of the group’s work.

(Written in collaboration with Sue Hackne, WayOut Rural Victorian Youth and Sexual Diversity Project, Cobaw Community Health, Kyneton)

local level simply do not have the resources or the skills to match these activities. This is an important point because it alerts health workers to the problems inherent in trying to emulate (and undo) the larger campaigns run by the advertisers. Local initiatives will have more impact when they are based on thorough knowledge of the prospective audience (John-Leader et al 2008; Nelson et al 2008). Added impact can be gained if they can be planned to coincide with a national media campaign about the issue, or a national ‘awareness week’. Calendars of national campaigns are available and can be a valuable resource to assist planning to make the greatest impact locally. However, at other times, especially where the budget is small, or it is a specific local issue, workers may need to get their message across by developing their own media resources. It may be more appropriate for a health worker to draw on the expertise of a graphic artist or advertising agency than to prepare materials ‘in-house’; the combined expertise will be more successful than acting alone.

Benefits of social marketing

National awareness campaigns can be ‘tagged’ onto local community-driven activities, thus gaining greater awareness of the issue, enhancing the credibility of a local project and bringing efficiencies in program planning.

National awareness campaigns can be ‘tagged’ onto local community-driven activities, thus gaining greater awareness of the issue, enhancing the credibility of a local project and bringing efficiencies in program planning.

Social marketing strategies can be used to reflect community values and create a sense of ownership towards significant issues in a community.

Social marketing strategies can be used to reflect community values and create a sense of ownership towards significant issues in a community.

Knowledge is itself enabling and empowering. Thus, social marketing messages should provide an ‘action plan’ informing the person what to do if they decide to take action on the issue (see Chapter 7).

Knowledge is itself enabling and empowering. Thus, social marketing messages should provide an ‘action plan’ informing the person what to do if they decide to take action on the issue (see Chapter 7).

Locally relevant social marketing approaches can bring forth a groundswell in networks seeking change in an issue affecting the community.

Locally relevant social marketing approaches can bring forth a groundswell in networks seeking change in an issue affecting the community.

At a national level social marketing can enhance people’s understanding of complex issues using short, accessible and memorable messages, especially to groups who may not access more traditional health education resources.

At a national level social marketing can enhance people’s understanding of complex issues using short, accessible and memorable messages, especially to groups who may not access more traditional health education resources.

Can we sell health like we sell tangible commercial products?

Millions of dollars are spent annually on advertising unhealthy, but profitable, products. Health workers, even when they are supported by national media campaigns, are in no position to match the extent to which unhealthy products are marketed — they simply do not have the same financial resources at their disposal. However, social marketing strategies can be a form of advocacy directed at policy-makers, manufacturing, commercial and government systems, and social structures just as readily as they can be directed at the individual (Egger et al 2005). The very successful HomeSafe.WorkSafe social marketing campaign for WorkSafe Victoria is an example of social marketing directed at commercial enterprises and individuals. It emphasises the responsibility of employers to provide safe working conditions for employees, and is supported by workplace protection policies (WorkSafe Victoria 2008).

A question of ethics in social marketing

Key criticisms

The key criticisms of social marketing are:

Stereotyping — in order to generate wider appeal the ‘ideal’ type is used (young, blond, beautiful). The ‘target’ audience for the message may not associate themselves and their situation with the message.

Stereotyping — in order to generate wider appeal the ‘ideal’ type is used (young, blond, beautiful). The ‘target’ audience for the message may not associate themselves and their situation with the message.

It may ignore the social, economic and environmental determinants of health. Messages are usually short and cannot accommodate wider social issues. This has potential to reinforce the disadvantage of disadvantaged groups, and raises the potential of ‘victim blaming’ (discussed in detail in Chapter 2).

It may ignore the social, economic and environmental determinants of health. Messages are usually short and cannot accommodate wider social issues. This has potential to reinforce the disadvantage of disadvantaged groups, and raises the potential of ‘victim blaming’ (discussed in detail in Chapter 2).

It has a single issue focus, rather than emphasising holistic wellbeing.

It has a single issue focus, rather than emphasising holistic wellbeing.

Social marketing, despite its applicability at social and policy levels, has generally been used as an individual, behaviour-change strategy.

Social marketing, despite its applicability at social and policy levels, has generally been used as an individual, behaviour-change strategy.

Analysing the audience

Successful social marketing campaigns achieve their aim of creating awareness of an issue or bringing about change because they understand the characteristics of their audience; their knowledge, attitudes, values and beliefs. Gathering information to clearly understand the audience enables the strategy to be specifically targeted at a small, fairly homogenous priority audience. The aim is to address and build on existing knowledge and beliefs and to correct misconceptions that are impeding adoption of healthier actions. Using a planning model, such as the Health Belief Model (see Chapter 7) at this stage of planning will enable a broad understanding of the audience segment. Good preparation, making use of research data and pilot-testing ideas with the audience, such as using focus groups, is essential to ensure the expected effects are achieved (Nelson et al 2008). Understanding the characteristics of a sub-set of the wider audience, who have relevant characteristics in common, and directing the message to them, will have more impact. ‘Segmenting’ the audience in this way will mean the strategy is likely to ‘reach’ the priority group, saving money and effort entailed in a ‘one-size-fits-all approach’, and it will help prevent the possibility of failing to engage with the group(s) you want to reach most (Egger et al 2005; Kotler et al 2002).