Chapter Nine. Social determinants of health

Key points

• The influence of social determinants on health

• Approaches to addressing the social determinants of health

– Legislation and regulation

– Strengthening disadvantaged communities

– Supporting individuals

• Tackling social determinants

– Income and poverty

– Employment and unemployment

– Crime and violence

– Housing

– Sustainability, regeneration and renewal

– Transport

OVERVIEW

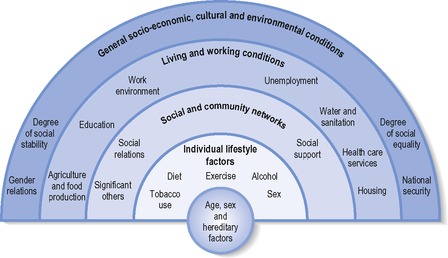

Health determinants are those factors that influence health. Several models of health have attempted to show the interconnectedness of social, economic, environmental, behavioural and biological factors. Dahlgren and Whitehead’s (1991) model, for example (see Figure 9.1 below), defines the determinants of health as individual lifestyle factors, social and community influences, living and working conditions, and general socio-economic and environmental conditions.

|

| Figure 9.1 • The main determinants of health (from Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991). |

This chapter discusses the social determinants of health – those structural factors that impact on health and are beyond any individual’s ability to change. The WHO (http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ accessed July 2009) defines social determinants of health as:

the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices. The social determinants of health are mostly responsible for health inequities – the unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between countries.

Various factors have been identified as social determinants of health by different documents. A UK working group identified social class, stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food and transport as key social determinants (Marmot and Wilkinson 2006). Canadian workers identified aboriginal status, early life, education, employment and working conditions, food security, gender, healthcare services, housing, income, social safety net, social exclusion, unemployment, and employment security as key social determinants of health (Raphael 2008).

These determinants are amenable to change, especially at the collective, community or social policy level. At the macro level the social, economic and physical environment can be changed in significant ways, affording more health-promoting choices and opportunities to people. At the meso level, communities can be supported to address collectively the impact of social determinants on their health. At an individual level, practitioners can work with clients to enable them to overcome the constraints and limitations on their lives and health imposed by social determinants. This chapter first discusses the concept of health determinants and the evidence showing their impact on health. It then goes on to consider action and interventions at different levels to implement change in health determinants. Evidence demonstrating the effect of interventions tackling socio-economic conditions, environmental conditions, and social and community life on health status and examples of effective interventions are given to illustrate the range of health-promoting activities.

Introduction

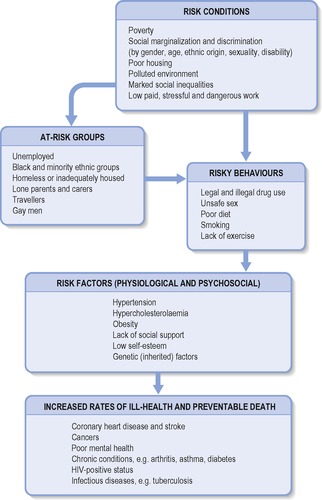

Risk conditions are social structures such as poverty or poor quality housing that are associated with poor health. Figure 9.2 shows how the effect of risk conditions (e.g. social marginalization) is directly linked to risk factors (e.g. lack of social support) and is also mediated by risky behaviours (e.g. drug use). Risk conditions and risky behaviours give rise to physiological and psychosocial risk factors that are in turn recognized precursors to many causes of ill health and premature and preventable death. Figure 9.2 also shows how certain groups of people are more likely to experience both risk conditions and risky behaviour, leading to poorer health status. For example, unemployed people are more likely than the general population to be living in poverty and to be socially marginalized. This in turn leads unemployed people to be more likely to participate in risky behaviours such as smoking and the use of legal and illegal drugs, and thus to be at increased risk of developing a variety of diseases causing ill health and premature death. Risk conditions, risky behaviours and risk factors tend to cluster together and disproportionately affect certain groups of people.

|

| Figure 9.2 • The relationship between risk and health (adapted from City of Toronto 1991). |

Any one individual or community tends to experience the impact of different health determinants in an integrated way, as ‘quality of life’ or ‘well-being’. Whilst it is possible to isolate the effect of heavy traffic on lifestyles (being unwilling to let children play outside, unwillingness to walk or cycle in busy streets), the sum total of all the effects of traffic become subsumed under concepts such as stress or isolation, which are also affected by many other factors (e.g. housing, income). It is therefore difficult to demonstrate that any one health determinant is the primary cause of ill health. The plus side of this interconnectedness of different determinants of health is that interventions in any one field tend to have ripple effects in other fields. Social and community interventions demonstrate that it is possible to increase health and well-being through building and supporting factors that improve health, such as community safety, social capital and local income.

Addressing the social determinants to enable them to become health promoting is a daunting task that requires many discrete skills. First there is a need to establish the health links, proving that determinants can affect health both positively and negatively. This has already been accomplished by a variety of research studies endorsed by official reports (e.g. Acheson, 1998 and Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003). Most recently, the WHO set up the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health in 2005 to synthesize evidence on how to tackle the social determinants of health in order to achieve health equity, and to prompt different bodies and organizations to strive towards this goal. The Commission published its final report in 2008 (WHO 2008). This report made three recommendations to tackle the social determinants of health:

• Improve daily living conditions – the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.

• Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources – the structural drivers of living conditions – globally, nationally and locally.

• Measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action – train the workforce to tackle these determinants and raise public awareness about them.

Although the evidence exists, it still needs reinforcing in many different forums because traditionally public sectors have worked in isolation. Establishing that, for example, regeneration and renewal are part and parcel of health development work leads to the next logical step of joint planning, funding and working. This stage still presents many challenges and dilemmas for practitioners, which have been discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

For those public health practitioners who recognize the social determinants of health, other barriers remain. Acknowledging the scale of the problem can lead to a feeling of helplessness. Healthcare professionals may feel ill-equipped to address such problems, and relevant activities, for example, supporting communal interventions such as food cooperatives, are often seen as falling beyond their remit. Such a situation can lead to low morale and frustration. For many practitioners there is a strong professional ethos of one-to-one intervention that values and respects the individuality of each client. Factors common to people’s health problems, such as social isolation or unemployment, tend to be overlooked or are seen as posing additional burdens on health instead of being seen as the fundamental cause of much ill health and premature death. Practitioners may also underestimate the challenges faced by clients in relation to poverty or discrimination due in part to their own distance from such issues. This distance can lead to practitioners imposing advice or information that has little relevance to the lives of their clients.

Structural determinants of health have been recognized by the UK government and included in various health policy and strategy documents. The Acheson Inquiry (Acheson 1998) was a key document that fostered recognition of the need to address health inequalities and their underlying social determinants. Only 3 out of the 39 recommendations made by the Acheson Inquiry were specifically directed at the health service. This was followed by ‘Tackling health inequalities: A programme for action’ (DH 2003) and a review of progress (DH 2008). The 2008 review identified five key areas: early years and parenting, work experience, equality of opportunity, mental health services, and coordination of action locally and nationally.

Whilst there is much support for tackling inequalities and health determinants together, certain strategies need to be implemented in order to achieve results (Exworthy et al 2003):

• mainstreaming funding and interventions so that tackling inequalities becomes part of the health or other service’s core business

• closer monitoring of the impact of interventions designed to tackle health determinants

• evaluation and research designed to assess the impact and outcomes of strategies.

Legislation and regulation are two of the most effective means to change infrastructure. They demonstrate a common view of what constitutes health risks and what actions should be taken to minimize harm. Legislation often sets minimum standards that have to be met, for example for air quality, wages, safety in the workplace, and housing. This approach requires agreed upon standards based on some form of evidence plus a monitoring and enforcement body to ensure compliance. There also needs to be an adequate infrastructure of trained and resourced inspectors to enforce the standards. Different professions each have a distinctive role to play. For example, environmental health officers (EHOs) are responsible for monitoring and enforcing standards for many health determinants including air pollution, food safety, housing and workplaces, whilst the police force is responsible for public protection and crime detection, and public health specialists are responsible for managing and controlling outbreaks of infectious diseases. Trading standards officers have also been identified as contributing to public health through their role in monitoring faulty goods and workmanship and enforcing the laws regarding the sale of tobacco, alcohol and solvents.

There may be tensions in the practitioner-client relationship if the practitioner has an enforcement or regulatory role. Having a regulatory role gives added authority to the practitioner, but this may have a downside. Some practitioners may feel clients will be less open and trusting if they feel they are being checked upon. Conversely, practitioners may feel clients will be more receptive and willing to take advice on board if they know there is an element of enforcement of standards involved.

One of the benefits of legislation is that it is an ‘upstream’ intervention that directly addresses the social determinants of health. For example, if poor quality housing is upgraded using minimum standards, then eventually no one will be living in substandard housing. This is of course an over-simplification. In practice, standards are constantly being revised, and there is always a shortfall between standards and what happens in real life. Some practitioners feel in addition that tackling determinants of health is a diversion from their primary role and expertise, which is working with individual clients. Many practitioners shy away from activities at a policy level regarding this as political action. As noted in Chapter 4, practitioners are engaged in political activity when they are implementing policy. They also have a clear role in influencing the policy agenda (e.g. the input of learning disabilities nurses into government policy in the White Paper Valuing People (DH 2001)) and in monitoring the effects of policy.

Strengthening disadvantaged communities through targeted interventions, regeneration and renewal is another popular approach to addressing the social determinants of health. This aims to strengthen the community fabric, building and releasing social capital and thus enhancing skills and self-esteem. Foundations for Health Promotion, edn 3 (Naidoo and Wills 2009) outlines the role and challenges of community development in promoting health including the non-statutory nature of the activity and the ambiguities surrounding professional education and training in a field which aims to break down professional/lay barriers and promote participation and equality.

The third distinct approach is targeted at individuals and aims to provide opportunities for people to tackle or overcome constraining influences on their health. For example, providing opportunities for adult education and training will help people find and retain paid employment, thus enhancing employment and income, two key health determinants. Developing and recognizing skills that people may already have (e.g. child caring) through accreditation may reduce dependency and enhance self-esteem and self-efficacy. Providing services for individuals also has the benefit of providing direct inputs to those most at need. The direct face-to-face interaction implied by such an approach readily conforms to the model of individual client-practitioner relationship underpinning most professional education in the healthcare services. A major limitation of this approach is that it follows a ‘downstream’ rather than an ‘upstream’ approach. Supporting people to overcome the constraints of their circumstances will help those individuals, but if nothing is done at source to tackle the causes of their disadvantage, other individuals will take their place, living in poor housing, on low incomes, without secure employment. This cycle will only be disrupted by removing the causes of disadvantage at their source.

In practice, all three approaches are used by practitioners, and the strongest effects are found when the three different approaches build on and complement each other. Most practitioners will feel more at ease with one approach, and this provides another reason for partnership working (see Chapter 7) where different practitioners work together, developing their own area of expertise but working alongside others. So, for example, in any one locality, EHOs may be working to enforce quality standards in housing and minimum exposure to pollutants in the air; youth and community workers may be facilitating and supporting community projects such as walking and exercise programmes or peer education arts projects to reduce problematic drug use; and health visitors may be providing postnatal support programmes for new mothers to reduce social isolation.

This chapter considers the following socio-economic and environmental health determinants:

• income and poverty

• employment and unemployment

• crime and violence

• housing

• sustainability, regeneration and neighbourhood renewal

• transport.

For each health determinant, the research showing its impact on health is first reviewed, followed by examples of different kinds of strategies and interventions designed to tackle the determinant. In particular, interventions that can be undertaken by health and welfare practitioners are highlighted. Evidence about the effectiveness of different strategies is reviewed and discussed.

Income and poverty

Poverty is acknowledged worldwide as a determinant of ill health. Poor people are unable to afford the basics for good health – for example adequate nutrition, access to clean water, and sanitation. Whilst poverty affects certain regions disproportionately (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa) it also impacts differentially on different demographic groups such as women and children who are typically more vulnerable to poverty and its impact than men.

• 1 billion (out of 2.2 billion) children worldwide live in poverty.

• 25,000 children die each day due to poverty (Leon and Walt 2001).

• 27–28% of all children in developing countries are underweight or stunted.

• In 2003 10.6 million children died before the age of 5 and 1.4 million children die each year due to a lack of safe drinking water and sanitation (http://www.globalissues.org/article/26/poverty-facts-and-stats accessed 1/7/09).

Extreme poverty means that children cannot access a nutritious diet, clean water, adequate sanitation, preventive health services such as vaccination and immunization, or education.

Tackling the problem of global poverty and its impact on health requires sustained and coordinated action by a variety of stakeholders including affected countries, the developed world, financial and banking institutions and the voluntary sector. The Millennium Declaration, endorsed by world leaders in 2000, is an example of coordinated action. The Millenium Declaration set 2015 as the target date for achieving most of its goals (United Nations 2007). At the midway point, progress has been made, although not sufficient to meet the goals.

• The proportion of people living in extreme poverty fell from nearly a third to less than one-fifth between 1990 and 2004.

• Child mortality has declined globally.

• Key interventions to control malaria have been expanded.

• The tuberculosis epidemic appears to be on the verge of decline.

However, many key challenges remain:

• Over half a million women (nearly all in developing countries) still die each year from treatable preventable complications of pregnancy and childbirth.

• There are still many underweight children in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (almost 30 million).

• AIDS remains a problem, and in 2005, 15 million children had lost one or both parents to AIDS.

• Half the population of the developing world lack basic sanitation.

The current global financial crisis presents a further challenge and will impact negatively on health, with an estimated increase in child mortality of between 200,000 and 400,000, largely driven by malnutrition (http://www.un.org accessed 1/7/09).

Whilst developed countries do not experience the scale of poverty-related health problems seen in developing countries, poverty and income remain key determinants of health status.

In developed countries income is the mediating factor that determines access to a host of variables related to health. The relationship between poverty and ill health is complex and can be seen in:

• reduced access to material resources such as income and good quality housing, neighbourhood and work environments

• constrained behavioural choices such as increased rates of smoking as a coping mechanism or reduced access to healthy food due to price and local availability

• psychosocial factors such as reduced social networks and feelings of low self-worth and self-esteem.

There is now an accepted evidence base that clearly demonstrates that poverty leads to poor health outcomes and excess mortality (Acheson, 1998, Benzeval et al., 2000 and OECD WHO, 2003). There is on-going debate about whether it is low income per se or income inequality that is the key factor determining poorer health and increased ill health (Shibuya et al., 2002, Sturm and Gresenz, 2002 and Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003). However, Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) provide robust evidence for asserting that inequality is the key determinant of a range of poor quality of life indicators, including poor physical and mental health.

Income, and hence poverty, is both absolute and relative. Absolute poverty refers to an income that is insufficient to pay for the basics of a healthy life – adequate nutrition, heating and housing (although defining basic minimum needs is not easy and is affected by cultural norms). Relative poverty is ‘when (individuals) lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong’ (Townsend 1979, p. 31). The key issue is whether a poverty line should be set in relation to a basic survival budget, or at a level of income that would enable people to participate in society and meet social and cultural needs. The definition of poverty used by the UK government (DWP 2002) is a household income below 60% of the median income level in that year. Other methods of establishing poverty levels may be the proportion of income needed to cover a basic food basket (used in the USA) or whether people can afford what are perceived to be necessities for life. ‘Necessities for life’ is a relative concept although there is considerable consensus about basic requirements. For example, a survey conducted by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Gordon et al 2001) found beds and bedding for everyone and adequate heating were commonly accepted as necessities for life.

Poverty is both a structural issue, affecting large sections of the population in a patterned and predictable way, and an individual issue, affecting and constraining every aspect of an individual’s life. Practitioners need to be aware of the constraints poverty places on people’s lives, and take this on board in their interactions with clients living in poverty.

Tackling poverty requires a multi-layered response that addresses the causes and effects of poverty. The government is committed to eliminating childhood poverty by 2020 and there is widespread support for policies to reduce poverty in the UK. Tackling the causes of poverty involves social policies focusing on:

• Providing social protection policies that cover the whole population.

• Interventions to reduce poverty and social exclusion at both the community and the individual level.

• Legislation to reduce vulnerable and minority groups experiencing discrimination and social exclusion.

• Removing barriers to social and health care and affordable housing.

• Reducing social stratification.

Source: Wilkinson and Marmot (2003)

The biggest and most significant anti-poverty policy is the social security system. Each year over £100 billion in social security benefits is distributed to over half the population (Alcock 2002). Universal benefits are paid in the UK on the basis of age or family circumstances, for example pensions and child allowances, but a significant element also constitutes welfare benefits, such as income support or unemployment benefit, which aim to relieve poverty. In addition to social security benefits, policies such as the introduction of a minimum wage, changes to the tax system, for example working tax credit and child tax credit, and changes to the national insurance system, are designed to ensure that being in employment leads to a higher income than being on benefits, and to help working people escape the trap of low income. Practitioners can help to ensure that clients are receiving their full benefit entitlement. Some practitioners may view such work as beyond their remit and area of expertise, but such schemes are practical and effective (see Chapter 5).

Social policy interventions to tackle poverty

Poverty (defined as incomes below 60% of the median) persists within the UK, and is especially prevalent amongst certain groups, for example single parent families and pensioners. In 1999 the government declared its commitment to end child poverty within a generation. Between 1998/1999 and 2003/2004 the number of children living in poverty dropped from 4.1 to 3.5 million (DWP 2005 cited in Asthana and Halliday 2006). In 2002/2003 one-fifth of pensioners were living in poverty and a further 15% were just above this level (Evandrou and Falkingham 2005 cited in Asthana and Halliday 2006) (Table 9.1).

For the working population, greater employment, or ‘work for those who can’, has made the most significant contribution to reducing poverty, but there is a limit to how much further these measures can contribute. Changes to the tax and benefits system have particularly benefited those with children and low earners but has disadvantaged others, such as those receiving incapacity benefit. Changes in indirect taxation (such as increases in tobacco tax and TV licence) negatively affect those on low income, for whom such taxes represent a significant proportion of total income.

At a local level, initiatives such as credit unions or local exchange trading schemes (LETS), which allow local trade by using credits instead of money, are an important means of facilitating and supporting local economies (http://www.letslinkuk.net/). LETS are also intended to maximize employment opportunities by building up skills. Schemes that maximize or increase income, or provide services and stimulate trade via credits, provide the most direct example of tackling the links between poverty and health.

Other strategies to tackle poverty may aim to strengthen individuals. For example, brief behavioural counselling to increase the consumption of fruit and vegetables amongst low income adults was found to be more effective than nutrition education counselling, leading to a 42% increase in the proportion of participants eating five or more portions a day (Steptoe et al 2003). Other interventions may focus on ‘living on a budget’, such as community kitchens. These schemes can be effective in getting people together to think about common problems and encourage social support networks. The challenge for practitioners is to avoid exacerbating problems by blaming people, explicitly or implicitly, for any unhealthy behaviour.

There is ample evidence of the link between low income and poor health, but historically there has been a separation between health and social care professionals, with income support work being undertaken by social care professionals. However, there are examples of interventions tackling poverty and low income where health practitioners play a key role. With training, support and resources, addressing low income and its effects on health can become a realistic and effective task for health practitioners. At a basic level, awareness and acknowledgement of the effects of low income on clients can enable practitioners’ core work, for example health promotion advice and education, to become more sensitive, appropriate and effective.

Employment and unemployment

There is a strong link between employment and health. For some people, the work environment can present hazards and health risks. Health and safety legislation covers employers’ statutory responsibilities to protect the health of their employees, but occupational ill health remains a significant problem. Social inequalities are reflected in the workplace, with workers from low socio-economic positions, Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups and migrant workers disproportionately employed in the most hazardous and unhealthy jobs.

In the UK conservative estimates of the contribution of work-related conditions to health each year are:

• 2000 premature deaths are caused by occupational disease

• 8000 deaths are caused in part by work conditions

• 80,000 new cases of work-related disease are registered

• 500,000 people continue to suffer from work-related ill health

• ill health accounts for 18 million lost working days

• occupational accidents and ill health are estimated to cost £7 billion.

Worldwide each year:

• 250 million occupational injuries are reported

• 160 million cases of occupational disease are reported.

Common mental health problems and musculoskeletal disorders are the main causes of ill health amongst the working age population. Stress at work plays an important role in contributing to the large differences in health, absence due to sickness, and premature death related to social status (Black 2008). Ill health amongst the working age population is estimated to cost Britain over £100 billion each year – more than the annual budget for the NHS (Black 2008). One way to reduce this burden is to shift practice from the cautionary ‘risk avoidance sick note’ culture to a more proactive approach focusing on what people can do rather than what they cannot do. A growing evidence base suggests that early interventions directed at people with short-term absence due to sickness is effective in reducing long-term absence due to sickness and the financial costs involved. This approach – the fit for work approach – is recommended in Carol Black’s (2008) review of workplace health.

For the majority of people, the association between paid employment and health is overwhelmingly positive. Paid employment provides people with an income, feelings of self-esteem, purpose and self-efficacy, and a social network. Employment provides goods or services that contribute to the national economy. Unemployment is a greater health risk than employment, and is strongly related to ill health and mortality. A good case can be made for targeting unemployed people and supporting them to move into paid employment as a health-promoting strategy.

Getting people into paid employment is a key national policy that is supported by many local initiatives. The approach is many pronged, and includes providing skills and training to enhance employability, helping people apply for jobs, supporting flexible hours through the provision of childcare, and providing transport to enable people to get to work. A pilot project – Pathways to Work – has been shown to be effective in increasing the employment of people on incapacity benefits, with the exception of those whose health condition is a mental illness (Black 2008). Specialist mental health services therefore need to be integrated into all ‘back to work’ services. Occupational health services need to be reinvigorated and integrated into mainstream healthcare provision.

Helping people to find employment

The Grimethorpe Jobshop is an example of a local intervention designed to assist people finding paid employment. The Jobshop is based in a community centre and offers help with CVs and applications as well as providing interview skills and further education for clients. Several other projects provide transport for workers and Northolt YWCA offers childcare and work placements to enable mothers to take paid employment.

Another strategy is to provide start-up loans to enable self-employment and the growth of small businesses. This approach was inspired by the example of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh which has helped millions to set up their own businesses and has a default rate of less than 3%. Community projects offer the benefits of direct accessibility and the provision of services tailored to local needs.

National policy addresses both health and safety in the workplace and unemployment issues. The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 set out the employer’s duty to protect the health, safety and welfare of employees and the wider public with regard to work processes. Dangerous substances used in the workplace are required to be satisfactorily controlled so that they pose no danger to the workforce and members of the public. Employees have a duty to take reasonable care with regard to health and safety issues, and to comply with any safety requirements. This Act also established the Health and Safety Executive and Health and Safety Commission, which are responsible for monitoring the workplace and ensuring that legal minimum requirements are met.

Individually, health workers can try to be more rigorous in considering the impact of employment and unemployment on health when seeing patients who are of working age. Routinely documenting people’s employment on their health records can be a first step. Monitoring and audit of records could then attempt to identify any patterns in illnesses related to workplaces. Practitioners can also be proactive about finding out what local back-to-work and fit-for-work initiatives exist, and making appropriate referrals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree