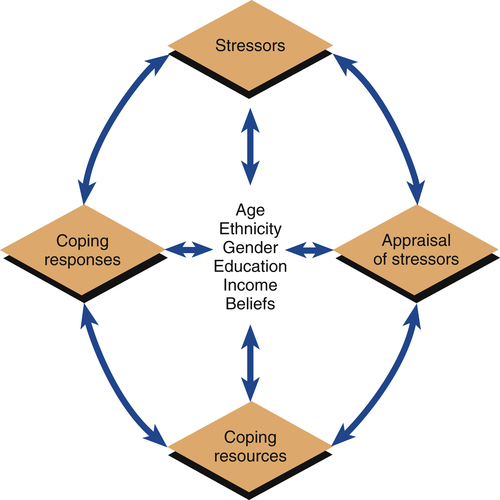

1. Describe the aims of cultural competency in psychiatric nursing care. 2. Analyze the social, cultural, and spiritual risk factors and protective factors in developing, experiencing, and recovering from psychiatric illness. 3. Apply knowledge of social, cultural, and spiritual contexts to psychiatric nursing assessment and diagnosis. 4. Examine the treatment implications of culturally competent psychiatric nursing care. Disparities are widespread in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness, as in other areas of health care (Miranda et al, 2008; Alegria et al, 2011; Lagomasino et al, 2011). The Surgeon General of the United States issued a report titled Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity (USDHHS, 2001) that emphasized the significant impact that sociocultural factors have on the mental health of all people. Its main message was that culture counts. The report underscored the following points: • Mental illnesses are real, disabling conditions that affect all populations, regardless of race or ethnicity. • Striking disparities in mental health care are found for racial and ethnic minorities. • Disparities impose a greater disability burden on minorities. • Racial and ethnic minorities should seek help for mental health problems and illnesses. These social, cultural, and spiritual characteristics can impact the person’s access to mental health care, the risk for or protection against developing a certain psychiatric disorder, the way in which symptoms will be experienced and expressed, the ease or difficulty of participating in psychiatric treatment, and the ability to achieve recovery. Thus quality psychiatric nursing care must incorporate the unique aspects of the individual into every element of practice and be based on an understanding of the importance of culture, as outlined in Box 7-1. Cultural competency is a necessary step in the elimination of disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness, and is essential in patient-centered psychiatric nursing care. A specific competency for nurses, as defined by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2008), states that patient assessment, treatment, and evaluation are improved by applying knowledge of cultural factors, using relevant data, promoting quality health outcomes, advocating for social justice, and engaging in competency skill development. Culturally competent nursing practice requires far more than recording the patient’s age, gender, ethnicity, and religion. It must first be based in desire, awareness, and understanding. In addition to being knowledgeable, skilled, willing, and concerned, the culturally competent nurse must be self-aware and self-reflective (Secor-Turner et al, 2010; Hoke and Robbins, 2011). Questions that the nurse can ask to assess one’s cultural competency are presented in Box 7-2. Five areas of cultural competency for nurses have been identified (Campinha-Bacote, 2009): • Cultural desire—the motivation of the nurse to want to engage in the process of becoming culturally competent • Cultural awareness—the conscious self-examination and in-depth exploration of one’s own personal biases, stereotypes, prejudices, and assumptions about people who are different from oneself • Cultural knowledge—the process of seeking and obtaining a sound educational base about different cultures including their health-related beliefs about practices and cultural values, disease incidence and prevalence, and treatment efficacy • Cultural skill—the ability to collect relevant cultural data regarding the patient’s presenting problem and accurately perform a culturally based assessment • Cultural encounters—the deliberate seeking of face-to-face interactions with culturally diverse patients Effectiveness in these five areas provides evidence of culturally competent psychiatric nursing care that is both appropriate and high quality (Williamson and Harrison, 2010; Wilson, 2011). Cultural competency requires the nurse to ask the patient informed questions that are free of bias (Tillett, 2010). For example, a study of the association of ethnicity and sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, or bisexual) with risk of suicide attempt in black, Caucasian, and Latino youth found that young age and substance abuse behavior did not predict risk of suicide attempt. Instead, the risk of suicide attempt was associated with daily life experiences with multiple sources of stigma, bias, prejudice, and discrimination related to their sexual orientation and ethnicity (O’Donnell et al, 2011). These findings show the value of general cultural knowledge and the need to ask patients about their specific personal life experiences. The concept of risk factors and protective factors is important to understanding how people acquire, experience, and recover from illness (Carpenter-Song et al, 2007). They develop over time and may change with personal circumstances. These factors are the same as the predisposing factors that nurses assess in the Stuart Stress Adaptation Model of psychiatric nursing care (Chapter 3). Understanding the risk and protective factors involved in health and illness is essential in the prevention, early detection, and effective treatment of both physiological and psychological illnesses. • Risk factors are individual characteristics that can increase the potential for illness onset, decrease the potential for recovery, or both. • Protective factors are individual characteristics that can decrease the potential for illness onset, increase the potential for recovery, or both. Six patient characteristics, influenced by social norms, cultural values, and spiritual beliefs, have been shown to be predisposing factors related to mental health and mental illness. These factors are age, ethnicity, gender, education, income, and spirituality. They influence the patient’s exposure to stressors, appraisal of stressors, coping resources, and coping responses, as described in the Stuart Stress Adaptation Model (Figure 7-1). Findings about these risk and protective factors and their possible health effects are described in the following sections. Box 7-3 lists some sociocultural trends and their influence on the health care system. In contrast, patient ethnicity also can have direct and indirect negative effects on the development of and recovery from psychiatric disorders and access to health care services. Many minority individuals lack medical insurance or access to health care providers (Kovandzic et al, 2011). Difficulty with language and communication or lack of knowledge in how to negotiate the mental health care system also limits their ability to receive needed care. Stigma is associated with mental illness, and this can be another barrier for those in need of mental health services (Pope, 2011). Ethnic minority groups, who may already confront prejudice and discrimination because of their group affiliation, often suffer a double stigma when faced with the burdens of mental illness. This is one reason why some ethnic minority group members who would benefit from mental health services decide not to seek or accept recommended treatments (Oakley et al, in press). Differences exist in the prevalence of certain disorders among various ethnic groups and in their use of mental health services (Hatzenbuehler et al, 2008; Keyes et al, 2008). Misdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and undertreatment are particular areas of concern (Hampton, 2007). For example, African-American men are less likely to be diagnosed with depression and anxiety and more likely to be diagnosed as psychotic or paranoid (Metzl, 2009). In turn, the observation that African-American men can be more likely to receive this diagnosis increases the stigma of mental illness in some African-American communities.

Social, Cultural, and Spiritual Context of Psychiatric Nursing Care

Cultural Competency

Risk Factors and Protective Factors

Ethnicity

Social, Cultural, and Spiritual Context of Psychiatric Nursing Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access