Chapter Five. Social capital and health

Sarah Cowley

Introduction

Social capital is of interest in a wide range of fields, including business, community relations, crime, economics, education, politics and health. It is a complex concept, which seemed to burst on to the scene in the 1990s, bringing enthusiasm and scepticism in almost equal measure. Although social capital is very important for health and health inequalities, it is also a highly contested concept within the field of social theory and its importance for public health is not well understood. The literature is voluminous and expanding exponentially, so selected examples are used in this chapter to provide an explanation of what it is and why it is considered so important to health. Then, the major criticisms will be outlined, before explaining the embedded meanings and confusions that have created controversy. Some of the responses that aim to unravel the tangle of critique will be offered, before concluding with some practical examples showing the value of social capital in practice.

Social capital: enthusiasm

The ownership of capital is considered an advantage, and social capital may be viewed as the advantage gained by an individual or a group of individuals (such as a community) as a result of being part of a social network (Hean et al 2003). At a common sense level, this straightforward definition seems logical and helpful; Cowley and Hean (2002) expand by offering examples from primary healthcare. An elderly patient being given a lift to a surgery by her daughter has received practical support by virtue of the fact that she is part of a family network, for example. Or an isolated parent, who has no friends to commiserate with the difficulties in coping with a young, crying baby, is at a disadvantage compared to the person who can tap into informational, emotional and social support; this is quite apart from (and in addition to) any practical help that may be available through a friendship network. At a more general level, there is an advantage for those living in communities where everyone knows and trusts their neighbours, extending a helping hand in times of need in the realistic expectation that, when the situation is reversed, the favour will be returned.

As well as networks, resources such as trust and support, norms of cooperation, reciprocity, participation and solidarity with community members are also considered central to the idea of social capital (Putnam 1993). In a qualitative analysis of two community projects, for example, Campbell et al (1999)identified certain key characteristics that marked the presence of social capital, while Putnam (2004) provides an updated list of mechanisms through which social capital may work (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1

Describing social capital

| Characteristics of social capital in two communities (Campbell et al 1999) | Mechanisms: macro and micro (Putnam 2004) |

|---|---|

Local identity: sense of ‘belonging-ness’ Meeting life challenges Trust Reciprocal help and support Attitudes to local government Formal and informal group memberships Subjective perceptions of ‘community’ including: Respect and tolerance Gossip Safety from crime Children’s freedom of movement Neighbourliness Reciprocal help and support Local identity Living and working conditions | Social support Communications patterns Social identity and risk behaviour Access to resources (medical and otherwise) Resolution of dilemmas of collective action Physiology (e.g. stress levels) Disempowerment Isolation |

Similarly, Cowley and Billings (1999) recorded the ‘resources for health’ available to help promote positive health; these included being able to turn to family and friends for help and support, relying on neighbours and neighbourhood facilities like schools, nurseries and transport. Some of these resources are examples of what has been called the ‘civic society’. This includes an expectation that there will be reliable services and facilities, although those in turn depend upon good government and the forms of participation (voting, political activity, democracy and so on) identified by Putnam (1993) in his seminal text about civic traditions in modern Italy.

Social capital and health

In this first text, Putnam (1993) suggested that health depended upon factors like diet and lifestyle, which are beyond the control of democratic government; he had reversed this opinion by the time his next book was published seven years later (Putnam 2000). There, he stated that, ‘Of all the domains in which I have traced the consequences of social capital, in none is the importance of social connectedness so well established as in the case of health and well-being’ (p. 326).

This enthusiasm is mirrored elsewhere. A discussion paper prepared for the British Cabinet Office (Performance and Innovation Unit (PIU) 2002) described the ‘explosion of interest’ and exponential growth in academic publications in social relationships, norms and networks since about 1995. In reviewing that massive literature, they concluded that ‘overall, the evidence described in this paper from a range of sources using a variety of methods for the beneficial effects of social capital is impressive’ (p. 5). In the fourth edition of Health for All Children, Hall and Elliman (2003) state that ‘a growing body of evidence suggests that social capital is as important a predictor of health outcomes as absolute levels of wealth or poverty’ (p. 32). The evidence continues to expand. Petrou and Kupeck (2008), for example, analysed data from a large, nationally representative sample (the 2003 Health Survey for England), and showed that poor measures of health status were significantly associated with low stocks of social capital across the domains of trust and reciprocity, perceived social support and civic participation. Comparing the ‘social capital best case’ with a notional worst-case scenario, they calculated that individuals from the ‘worst-off’ situations would be 79.5% less likely to report very good or good health status. This analysis draws attention to the significance of social capital for understanding health inequalities, which is one of the key areas of interest for this field.

Social capital and health inequalities

Health inequalities have become one of the major challenges to public health, as they are globally pervasive and the reasons underlying them are poorly understood. Much of the interest in the concept of social capital has come from researchers trying to explain why these arise, particularly within and between resource-rich countries.

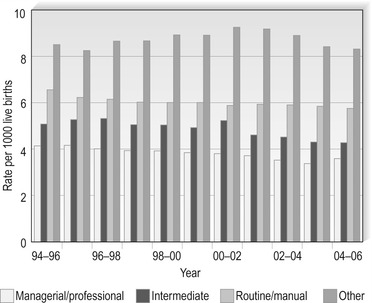

It is clear that absolute poverty is a major cause of the different patterns of morbidity and life expectancy between the developed world and areas where inadequate food, poor or contaminated water supplies and lack of high-quality healthcare lead to disease and early death. However, once countries have passed beyond what Wilkinson (1996) terms the ‘epidemiological transition’, when they are sufficiently well developed to ensure basic physical requirements for health for their whole population, and starvation and death from major epidemics are no longer key concerns, a pattern of health inequalities remains. Even in the absence of absolute poverty, across the developed world, there is a social gradient in mortality from many illnesses, and in life expectancy overall. The pattern of infant mortality, shown in Figure 5.1, illustrates this gradient; even though the absolute figures have improved overall, there is a persistent gap between babies born to managerial and professional groups (the best off) and those in families headed by a ‘routine and manual’ worker. The outlook for infants born to the poorest and most excluded groups, including students, unemployed people and those who have never worked (the worst off), is worse still. Similar patterns pertain for life expectancy.

|

| Figure 5.1 •England and Wales. Three-year average infant mortality rates by social economic group. Source: Office for National Statistics. NB; there was a change in the method for classifying social economic groups in 2001. |

In the USA, Kawachi et al (1997) analysed survey data from 39 states in terms, borrowed from Putnam, of social networks, trusting relationships and cultural norms that act as resources for individuals and facilitate collective action. Each of these elements of social capital showed a strong inverse correlation with all-cause mortality rates, after adjusting for age. Soon, a raft of studies emerged, each showing a similar pattern across the developed world, both within and between countries (Wilkinson and Pickett 2006). In each case, as well, mortality and morbidity follow a gradient, with people living longer, healthier lives at each step up in their status and wealth.

Poverty is a key mediator, and lack of sufficient money for good food, heat and housing matters immensely to people’s health. However, to repeat the key point, inequalities are distributed across a gradient, with each step up showing an advance in health outcomes, right from the least to the most well off. This pattern cannot be explained by the presence or absence of absolute poverty. Nor, Wilkinson (2006) argues, do the material privations of having a house with a smaller lawn to mow, or one less car, seem plausible explanations for these differences. Instead, there seems to be some way that health inequalities are related to psychosocial factors, affecting the whole population and not just those who are living in poverty. As Moore et al (2006) identified, a search for this explanation, encouraged by the ideas suggested by Wilkinson (1996) and Putnam (1993), led to public health interest in social capital. Studies using a variety of proxy measures, such as the extent of public participation or neighbourhood trust and relationships, began to emerge soon after.

Social capital: scepticism

Given the apparently immense benefits to be gained from social capital, it might seem churlish to raise any doubts or questions about it. However, there are a number of concerns, which have given rise to a rich and competitive literature, particularly in the economic and sociological journals, which can seem confusing to anyone outside those disciplines, or even within them. Some of the debates seem bitter and critical, while others build systematically and courteously upon what went before.

Lack of clarity

One of the main concerns is the lack of clarity and conceptual confusion that surrounds much of the work about social capital. Even the enthusiasm expressed by the Performance and Innovations Unit was tempered by the plethora of definitions encountered in their literature review, leading them to caution about the potential mis-specification or ambiguity in some of the models used in the empirical literature (PIU 2002). Opinions are divided about whether this is because social capital is a falsely inflated concept (Labonte 1999) or because of the lack of clear guiding principles underpinned by a sound theoretical base (Lomas 1998, Wall et al 1998). Whatever the reason, unclear concepts create problems for research.

Kawachi et al (2004), for example, identified 31 studies from across the world, which illustrate the wide variability of definitions and unclear concepts. The results showed that the presence of social capital led to better health outcomes in the large majority of studies, but the indicators used varied widely (Box 5.2). The authors highlight a key difference: that some measures (mortality and crime rates, for example) relate to collectives or whole populations, while others relate to aggregated measures (such as self-rated health and self-esteem) drawn from individual respondents. This raises the question about who ‘owns’ social capital, and whether it is legitimate to measure it in a community, but apply it to individuals, or vice versa. Without theoretical and conceptual clarity about exactly what is being measured or why, it is hard to have faith in the results, and Hean et al (2003), among others, have called upon researchers to explain the mechanisms being measured in theoretical terms.

Box 5.2

Indicators and health outcomes: measures used across 31 studies of social capital, 1997–2004 (derived from Kawachi et al 2004)

| Indicators of social capital (or lack) | Health outcomes: measures used |

|---|---|

Social trust, social cohesion Social mistrust/distrust Civic engagement and/or participation Electoral/voting participation Community organizations Workplace cohesion Crime rates Membership of organizations or associations Density of association/local networking Volunteering Social involvement Informal sociability Informal social control Reciprocity Help from organizations Lack of helpfulness Collective efficacy Close-knit; shared values, get along with each other Parental attachment to community Parental sense of community | Mortality rates and life expectancy Firearm violent crime; homicide rates Self-reported sense of insecurity Low birthweight Self-rated health/poor health/physical health Teen birth rates Adolescent sexual risk/protective behaviours Rates of sexually transmitted diseases Binge drinking Food security General health Mental health Self-esteem, satisfaction and behaviour Proportion of residents/children receiving mental health services Psychiatric hospitalization Alcohol and drug service use Tuberculosis rates Leisure time physical inactivity/walking activity Child behaviour problems Medication: hormone replacement therapy; antihypertensive medication |

Lack of theoretical awareness

Concerns about a lack of clarity are linked with the second major area of criticism, which can be summarized as a lack of theoretical awareness. Critics suggest that much of the social capital literature is merely rewriting well-established theories; social capital is described as ‘old wine in new bottles’ or as a ‘catch-all phrase’ for social support and democratic theory (Berkman et al 2000, Edwards and Foley 1998, Labonte 1999, Muntaner 2004, Portes 1998). Such writers point out that we have known the importance of social circumstances on the quality of life and health since the work of 19th-century sociologist, Emile Durkheim. The collective impacts of social relationships and social trust on health have been very well documented, and there is an expansive empirical literature about both social networks and the different forms of community, including its cohesion. Social capital literature is viewed as naive and uninformed by these critics, who suggest it fails to take sufficient account of existing social theories. Szreter and Woolcock (2004) suggest that the majority of the literature about social capital and health can be divided under two headings: that which is concerned with how psychosocial mechanisms, such as social support, affect health and that which purports to explain health inequalities (as outlined above). These two large fields of interest were well represented in psychological and sociological literature long before social capital emerged as a concept of interest.

In exploring psychosocial mechanisms, Stewart-Brown and Shaw (2004) carried out a study that differed from those taking the community as a starting point, instead bringing the family into sharper focus. They hypothesized that the roots of social capital were embedded in relationships in the home during childhood, which would influence health in later life. By comparing the results of two systematic reviews with published birth cohort data across three cohorts (born in 1946, 1958 and 1970), they were able to provide strong evidence that the quality of relationships in the home in childhood has an impact on both physical and (particularly) mental health in adulthood, regardless of socio-economic circumstances. This important analysis identifies issues such as warmth, relationships, social support and the developmental importance of children growing up in circumstances that are conducive to trust and networking, so that as adults they might both accept trust and be the kind of person, or neighbour, who is trusted by others.

Despite the value of the work, reflecting the criticisms outlined above, Stewart-Brown and Shaw’s (2004) study of social trust and relationships would have been equally useful if the term ‘social capital’ had not been used. However, the study does underscore the potential for social capital to be both generated and used within relationships, which is the basis for the norms of reciprocity and obligation that arise in much of the social capital literature. In terms of measurement, it is important to know whether data are being drawn from a social capital user or generator, or from both (Hean et al 2003). This distinction is similar to one suggested by Snijders (1999) to distinguish between different social capital pathways. He suggested using the term ‘complementary’ to describe when one person has the social capacity to offer some element, such as support or information, from which another can benefit; and ‘symmetrical’ for when there is a collaborative or cooperative effort from which all parties can benefit equally. The distinction is important for researchers, so they know what to measure. In addition, it becomes important for practitioners and those interested in improving social capital in an area. Is it possible for an outside person, such as a health professional, to enable the generation of social capital through networks and groups, for example? Community development literature is divided on whether the activities of an insider or outsider, or lay or professional worker, are most effective; the social capital literature has not really engaged with these issues.

Negating power and poverty

Both a lack of conceptual clarity and the failure to specify the theoretical basis for social capital may be regarded as acts of omission. They are criticisms that have largely been taken on board by researchers in the field of social capital, with varying degrees of success. The third group of complaints represents more fundamental differences of opinion. Kanazawa (2006) is something of an outlier in the debates. He draws on evolutionary genetics to suggest that average intelligence quotient (IQ) as measured across countries provides a better explanation than social capital for international health inequalities, an idea that is given short shrift by Wilkinson and Pickett (2007), who reject the way he conceptualizes IQ.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access