SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

• Ageing and the skin

• Wound healing processes

• Importance of appearance

• Cultural influences related to skin care and adornment

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

• Assessment of the skin

• Assessment and management of a person with a wound

• Evaluation of the effectiveness of wound management

• Management of acute and chronic wounds

PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL KNOWLEDGE

• Nurse’s role in promoting skin health

• Nurse’s role in developing and maintaining quality systems of care

• The developing role of the nurse in skin integrity: clinical, educational, professional and ethical consideration for practice

PERSONAL AND REFLECTIVE KNOWLEDGE

• Case studies

INTRODUCTION

The skin or integument is a major organ of the body, providing a barrier between the internal and external environments. It is also an organ that is highly visible to others, and therefore any damage, alteration or deformity in its structure can cause not only physical but also psychological, social and environmental problems. Skin integrity is concerned with the maintenance of this barrier in its optimum condition.

The aim of this chapter is to provide the requisite knowledge and decision-making skills to enable nurses, within their role, to care for patients with skin problems, to reflect on current practice relating to skin care and encourage the maintenance of their own skin health.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

The biological section covers basic anatomy and physiology of the skin. The process of skin healing is explored. The importance of appearance and its effect on self-image is highlighted in the psychosocial section. Cultural influences are included.

Care delivery knowledge

Assessment of the skin and knowledge, skills and understanding required to assess, plan, implement and evaluate the care of patients with wounds are addressed in broad terms. A more in-depth discussion of the management of three common types of wound is provided.

Professional and ethical knowledge

The contribution of nurses to the development of quality systems of care relating to skin integrity is explored. Opportunities available to nurses in the development of their knowledge and expertise in different aspects of skin care are examined. Clinical, educational, professional and ethical considerations for practice are highlighted.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

BIOLOGICAL

STRUCTURE OF THE SKIN

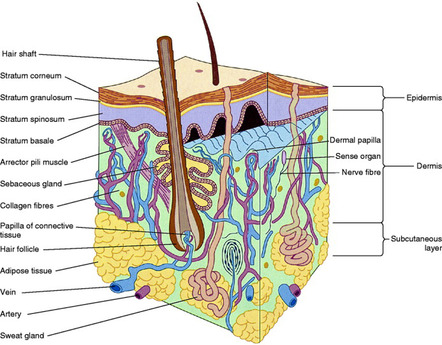

The skin is one of the largest organs in the body. An adult’s skin covers an area of about 2 m2 and weighs approximately 4.5–5 kg. Every square centimetre of skin contains approximately 125 sweat glands, 25 sebaceous glands, 250 nerve endings, 50 sensors to pain, pressure, heat and cold, approximately 1 m blood vessels, and millions of cells. Skin is made up of three main structures (Fig. 15.1):

• the epidermis or outer layer

• the dermis or base layer

• the skin appendages such as hairs, nails and glands.

|

| Figure 15.1 (from Montague et al 2005, with kind permission of Elsevier). |

These structures are also termed the integumentary system.

Epidermis

The epidermis is the outer or cuticle layer of the skin, and consists of several layers of cells. It contains no blood vessels or nerve endings and its main function is to protect the underlying dermis. It has four or five different layers of cells depending on its location. From the deepest to the most superficial these are the:

• stratum basale (or germinating layer)

• stratum spinosum

• stratum granulosum

• stratum lucidum (not present on hairy skin)

• stratum corneum (or cornified layer).

The greater part of the epidermis is made up of keratinocytes, the cells that produce the outer surface of the skin. Scattered among these cells are two other types of cells known as melanocytes and Langerhans cells.

Melanocytes are responsible for producing melanin, which produces the skin’s pigmentation or colouring. White and black skinned people have the same number of melanocytes per unit of surface area, but in black skinned people the melanocytes are more active and produce pigment at a faster rate. Melanin protects other cells of the skin against the damaging effects of strong sunlight. Exposure of the skin to the sun stimulates the melanocytes to produce more melanin. This reaction causes the characteristic darkening of the skin (suntan). Black skinned people are therefore better protected against the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

Overexposure to sunlight can cause sunburn and skin cancers such as malignant melanomas and non-melanotic skin cancers (NMSC), primarily basal cell and squamous cell cancers. The number of people developing skin cancers in England has been rising rapidly in recent years. Cancer Research UK (2005) state that malignant melanomas are diagnosed in approximately 8000 people each year in the UK and the incidence has quadrupled in British males between 1975 and 2001 and tripled in females. The increase in incidence is thought to be due to intermittent sun exposure of untanned skin during holidays and other outside activities. However, there is increasing concern and evidence regarding the use of sun beds and the development of malignant melanoma (Diffey 2007). A number of skin cancer and skin damage prevention campaigns and activities are important, including Sun Smart campaign (Cancer Research UK 2007). The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2006) guidelines provide advice on how healthcare services for individuals with skin tumours should be organized.

Diffey (2002) questioned the belief that the daily use of sunscreens all year round reduces chronic skin changes associated with sun exposure in the UK. Findings of the study showed that the use of sun protection products during the summer months could reduce the lifetime (70 years) UV exposure of a person by an equivalent of almost 40 years’ unprotected exposure, but there was almost no benefit from using the products between October and March in the UK.

Langerhans cells are thought to be important in the body’s immune responses. They absorb small particles of foreign material such as nickel in jewellery and are responsible for setting up the allergic reaction common in contact allergic eczema (dermatitis). The resultant rash usually clears up within 1 week following removal of the irritant once it has been identified. Key to managing this condition, in the long term, lies in identifying and avoiding contact with the allergen.

Dermis

The dermis is the deepest layer of the skin. It is composed mainly of connective tissue and contains fewer cells than the epidermis, the main ones being fibroblasts, which produce collagen, a protein that attaches the skin layers to the rest of the body with tiny elastic fibres. These fibres give the skin its suppleness and ability to stretch. The upper part of the dermis contains rows of projections known as dermal papillae, which bind the two layers of skin together at the dermal–epidermal junction. The dermis contains a good blood supply and is responsible for nourishing and maintaining the epidermis, which does not have its own blood supply. The dermis also contains sensory receptors to heat, cold, touch and pain.

Glands

Three types of glands are present in the skin:

• Sebaceous or oil glands secrete an oily substance known as sebum, which lubricates and protects hair and skin.

• Sudoriferous or sweat glands assist in the regulation of body temperature through evaporation.

• Ceruminous glands produce cerumen or wax, which is found within the outer ear where it protects the ear by preventing the entry of foreign bodies.

Information on hair and nails can be found in Chapter 14, ‘Hygiene’.

FUNCTIONS OF THE SKIN

The skin has five main functions.

Regulation of temperature

The production of sweat by the sudoriferous glands during hot weather helps reduce the body temperature through a process of evaporation. Changes in blood flow also occur. During hot weather peripheral blood vessels dilate, enabling heat loss by radiation. Conversely, in cold weather peripheral blood vessels constrict in order to maintain vital organs at an optimum temperature for functioning (see Ch. 7, ‘Homeostasis’).

Excretion

Sweat contains water, salts, urea, ammonia and several other compounds. During sweating small amounts of these substances are excreted.

Stimuli reception

The skin contains many different types of receptors. The most common are receptors to temperature, pain and touch. These provide information about the external environment.

Synthesis of vitamin D

The skin aids in the synthesis of vitamin D. The precursor to vitamin D, 7-dehydrocholesterol, is present in the skin and is converted to cholecalciferol in the presence of ultraviolet light. After further conversion in the liver and then the kidneys, 1,25-dihydroxycalciferol is produced. This aids in the absorption of calcium from the dietary intake.

Tortora & Grabowski (2003) identify two further functions of the skin: immunity, due to the action of the Langerhans cells; and as a blood reservoir, due to the ability to divert blood to muscles during exercise through vasoconstriction.

AGEING AND THE SKIN

During an individual’s lifespan, changes occur in the physical properties of the skin. In order to maintain healthy skin different requirements must be met at different stages of an individual’s life. For instance, during infancy the skin is delicate and until the child is continent the skin requires protection from the damaging effects of urine and faeces. Similarly, during adolescence skin changes result in increased perspiration and oil production, sometimes leading to the development of acne.

During pregnancy there is an increase in activity of the sebaceous glands and melanocytes, resulting in increased oil production and patches of darker pigmentation on the skin – commonly the linea nigra, which is a pigmented line down the abdomen, and chloasma, which are darker areas on the face often referred to as the ‘mask of pregnancy’. Although the skin has the ability to stretch, during pregnancy the increase in size of the abdomen can be so great that the collagen fibres rupture, leaving visible scars. These are known as striae gravidarum or ‘stretch marks’.

In old age, the production of cells slows down and they become smaller and thinner. The collagen and elastic fibres lose their shape and elasticity, and the amount of fat stored in the subcutaneous tissues lessens, resulting in skin wrinkles. There is a decrease in the number and an increase in the size of active melanocytes, producing concentrated areas of pigment commonly known as liver spots. There is also a reduction in the amount of intracellular fluid resulting in dry skin, which can lead to itching or ‘senile pruritus’, and increased skin fragility. The use of moisturizers or emollients can help to prevent excessive flakiness of skin.

For many people the desire to preserve a youthful complexion brings with it the necessity of a continued battle against the ageing process. There are two distinct types of skin ageing. Chronological or intrinsic ageing is the normal ageing process that occurs over time in all organs of the body. Photoageing or extrinsic ageing is connected to environmental factors, mainly ultraviolet light induced (Ma et al 2001). Photoaged skin is characterized by ‘wrinkling, sagging, mottled hyperpigmentation and yellowing’ (Sator et al 2002: 292). Although creams and lotions may result in a superficial improvement in skin texture altered by normal ageing, cosmetic surgery is becoming more and more popular. Protection of the skin against sun damage from an early age is the only way to combat photoageing. Prevention is better than a cure.

Liza Gordon is an 18-year-old student who enjoys holidays abroad with her friends. She also tops up her tan by using a sun bed regularly. She has been admitted to the day care ward for a biopsy of a ‘suspicious’ mole, which turned out to be benign. Liza is very concerned about her appearance and is anxious to protect her skin against sun damage and the long-term effects of ageing.

• What skin care advice would you give to Liza before discharge?

• Apart from advice to individuals, what other strategies are or could be put in place to reduce the effects of ultraviolet light/sun damage?

• Compare your answers with the Cancer Research UK (2007) Sun Smart campaign and the Sun Know How campaign developed by the Health Education Authority and the BBC (2000).

SKIN HEALING

Should the skin become cut or damaged, creating a wound, the process of healing has four distinct phases:

Skin heals by primary or secondary intention.

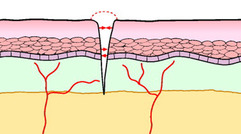

Primary intention

This type of healing occurs when the edges of the wound are opposed, as in a surgical incision. Healing tends to be rapid due to the close proximity of the wound edges (Fig. 15.2), and involves:

• Coagulation – within 8 hours following surgery the cut surfaces become inflamed, a blood clot fills the incision track, and phagocytes and fibroblasts migrate into the area.

• Inflammation – phagocytes begin to break down the clot, and cell debris and collagen fibres are produced by the fibroblasts and begin to bind the two surfaces together.

• Regeneration – after 3–4 days epithelial cells spread across the incision track, the section of clot above the new cells becomes a scab, the clot in the incision track is absorbed, and myofibroblasts draw the edges of the wound together by a process of contraction.

• Maturation – epithelial cells continue to be laid down until the full thickness of skin is restored.

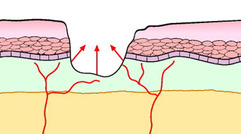

Secondary intention

This type of healing occurs where there is a significant loss of tissue or where the skin edges are not opposed, as in an ulcer. Healing tends to be slower, but the exact time will depend on the extent of the damage (Fig. 15.3). It involves:

• Coagulation – the surface of the wound becomes acutely inflamed and phagocytes start to break down the necrotic tissue.

• Inflammation – granulation tissue develops at the base of the wound and starts to grow up towards the wound surface.

• Regeneration – phagocytosis causes the necrotic tissue to separate, exposing a new layer of epidermal cells, and contraction occurs to reduce the size of the wound (as wound contraction is a normal process, it is important not to pack the wound with dressings unless specifically indicated, for example for a wound sinus, as it interferes with this process).

• Maturation – when granulation tissue fills the wound cavity and reaches the level of the dermis, epithelial cells migrate across the wound towards the centre, forming a single layer of cells. Epithelialization continues until full-thickness skin is restored.

Tissue viability experts are now using a slightly different definition of wound healing involving four major stages – inflammation, proliferation re-epithelialization and matrix formation/remodelling (Calvin 1998). These terms are not yet commonly used in physiology and tissue viability text but are terms to look for in the future.

Benbow (2005) uses the term ‘tertiary healing’ to describe a wound where there is a significant delay between injury and wound closure; for example, extensive tissue loss or dehiscence. Bale & Jones (2006) use a similar term, ‘healing by third intention’, to identify a wound containing a foreign body or infection that is left open until the problem has been resolved.

THE OPTIMUM ENVIRONMENT FOR WOUND HEALING

A variety of factors need to be present to create the optimum environment for wound healing to take place. These include:

• a good blood supply

• optimum temperature

• appropriate moisture

• oxygen

• freedom from contaminants and necrotic tissue

• freedom from infection.

Blood supply

Healing requires an integral blood supply to provide oxygen and nutrients to the developing cells. Reconstitution of the blood supply is termed angiogenesis and occurs during the regeneration phase of healing. Care must be taken not to disturb this process by the inappropriate use of dressings; for example dry dressings such as gauze can stick to wound beds, resulting in trauma when they are removed.

Thomas (2003), reviewing the literature, indicates that pain and trauma relating to the removal of dressings is a major concern to patients and health care professionals. There is confusion between the terms ‘adherent’ and ‘adhesive’, which are often used interchangeably. ‘Adherence’ should describe the interaction between the dressing and wound and, ‘adhesive’ should describe the interaction between the dressing and intact peri-wound skin. Thomas advocates the use of a new term – ‘atraumatic dressings’ – to describe wound products that, on removal, do not cause trauma to the wound site or the peri-wound skin. Dressings coated with soft silicone could be described as ‘atraumatic’.

Temperature

The optimum temperature for human cell growth is 37 °C. Wounds kept at a constant temperature of 37 °C will heal faster than those exposed to thermal shock (i.e. extreme changes in temperature). To keep wounds at a constant temperature, unnecessary wound cleansing and dressing changes should be avoided.

Moisture

The exudate produced by wounds, other than non-healing chronic wounds, contains nutrients, enzymes and growth factors that can aid the healing process. Lytic enzymes found in the exudate autolyse (break down) any necrotic tissue present, and growth factors increase the development rate of cells and result in less scarring. In such wounds, a moist wound environment facilitates wound healing, reduces the amount of tissue inflammation, produces less scarring and results in less pain for the patient. If the wound is allowed to dry out, a scab or eschar forms. This impedes cell migration and consequently slows down the healing process. Excessive exudate needs to be contained to prevent damage to the surrounding skin.

Exudate in non-healing chronic wounds is different in nature to that from acute wounds and has potentially harmful constituents which may inhibit wound healing (Vowden & Vowden 2003). Management of such exudate is part of an overall wound management approach to these chronic wounds, namely wound bed management (see Care Delivery Knowledge). An understanding of the role of exudate in the wound healing process is essential (see section on Annotated Further Reading: Vowden & Vowden 2003)

Oxygen

All cells require oxygen in order to develop and mature. An integral blood supply is therefore essential to ensure that cells receive an adequate oxygen supply in order to remain viable. The external administration of oxygen to the wound site, for example via an oxygen mask and tubing, will not benefit tissue perfusion, but will dry the wound site and delay wound healing.

Freedom from contaminants and necrotic tissue

The presence of foreign bodies and dead or devitalized tissue delays wound healing and provides a focus for infection, which will in turn also delay wound healing.

Freedom from infection

Wounds may be contaminated transiently or colonized by bacteria which do not affect wound healing adversely. Moore & Cowman (2007) suggest that whether or not an infection develops depends on the individual host’s response to bacteria present and the virulence of the bacteria. If wounds become infected, the bacteria present in the wound cause host damage and delay healing (see section on Annotated Further Reading: Benbow 2005). However, there is a stage called critical colonization that precedes clinical infection, causing delayed healing and subtle signs of infection (Collier 2002). Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of critical colonization to prevent overt clinical infection presents a challenge to health care professionals.

Moore & Cowman (2007) provide an overview of the European Management Association’s (2005) position document Identifying Criteria for Wound Infection and discuss its relevance and application to clinical practice. While they acknowledge that assessing the presence of infection is not an easy task, they consider that early recognition of wound infections is essential in the development of effective treatment strategies.

PSYCHOSOCIAL

THE IMPORTANCE OF APPEARANCE

Images in the media of suntanned, high profile individuals such as fashion models may help to encourage the idea that a suntan is both healthy and desirable. Accordingly, suntanned skin can promote a sense of psychological well-being. As a consequence, despite current health education concerning the dangerous effects of ultraviolet light, sunbathing – in either natural or artificial sunlight – remains a popular pastime. Naidoo & Wills (2005) recognize the challenges for health promoters in that the message to reduce exposure to sunlight is at odds with lay beliefs that sunlight is beneficial. It is necessary to address the conflict between the improvement to psychological health and its detrimental effect on an individual’s physical health. Gross (2005: 418) examines Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is a state of ‘psychological discomfort and tension’ caused by a person knowing that an action may cause harm, but at the same time participating in that action. Festinger’s theory can be useful for choosing between two activities that are equally attractive. This involves highlighting the undesirable features of each activity in order to help with the decision making process. Although this may help in deciding whether or not to sunbathe, it must be acknowledged that an individual may still decide that the psychological benefits of sunbathing are more important and therefore continue the activity.

You may wish to extend your personal reflection here into a debate with your fellow students on the choices to be made.

• Is an individual’s psychological or physical health more important?

• If it is necessary to make one dimension of health a priority, which would take priority for you at a personal level? Justify your decision.

• In your practice placement review the above debate in relation to one patient or client.

• Record key points in your debate and your conclusions in your portfolio.

Just as a healthy skin can help to promote a positive self-image, a skin disorder can have a detrimental effect. For thousands of years skin disorders have been regarded as unclean: lepers, for instance, have often been treated as social outcasts. It may be argued that certain more common skin disorders continue to evoke a less than compassionate reaction nowadays, particularly those that are visible, such as eczema or psoriasis. The impact of a skin disorder on a person’s self-image can depend very much on the individual’s ability to cope. If the disorder affects the person’s ability to carry out and meet their self-care needs, or if it causes stress to the individual or the family, it can seriously undermine their self-regard. The disorder can come to be viewed in a way that is out of all proportion to the problem itself and overshadow the individual’s entire life.

Self-image

It is important to understand that the nurse’s approach can have a significant effect on how the client responds to a skin disorder. Any signs of disgust, alarm or even fear may encourage the client to view their condition as offensive to others. Furthermore, the nurse needs to be aware of any signals that may be conveyed to the client. With thought, the nurse can project and encourage a more positive self-image. If the skin disorder is not infectious and does not require the use of gloves when handling, the client’s self-image can be enhanced if the nurse touches the affected area with unprotected hands. In addition, the client will benefit from being able to discuss any feelings about the condition with both relatives and the nurse. Moreover, a simple explanation of the aetiology (cause), and prognosis (probable course) of the condition may help the client to accept it.

Some conditions of the skin, for example burns, ulceration and extensive surgery, can cause great distress to both the client and the nurse. In order to help the client accept the condition, the nurse will first need to come to terms with it him or herself. Nurses often do not feel they have the skills required to provide the level of psychological support that clients may require (Clarke & Cooper 2001). Although these skills can be provided by training, this is an area where lay-led or voluntary service may be useful. Changing Faces is a charity set up to support facially disfigured people and their families (www.changingfaces.org.uk). (See Ch. 19, ‘Rehabilitation and recovery’, for information on dealing with body image changes.)

Rumsey et al (2004) surveyed 458 participants with visible disfigurements including burns, tattoos and skin conditions in order to establish their psychological needs. The results highlighted high levels of psychological distress when compared with normative values. 71% (n=325) expressed a moderate or strong desire for access to professionals with appropriate training to help them to deal with their appearance related concerns.

CULTURE AND APPEARANCE

Some cultures use skin decoration to produce the opposite effect. The Tuareg paint their skin with turmeric to make themselves less desirable and therefore less vulnerable to evil spirits. In Ethiopia, the Surma women insert clay discs into their lower lip to cause it to protrude. It is thought that this was first done to make the women less desirable to slave traders.

Beauty is a matter of subjective judgement (i.e. ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’). To some extent, the skin plays an important part in the perception of an individual’s attractiveness, and for hundreds of years has been decorated in many ways to enhance or diminish its appeal (see Evolve 15.1).

Cosmetics

These are used to accentuate attractive facial features and disguise imperfections. Cosmetics can have religious or cultural significance; for example, the bindhi is traditionally a red or maroon dot worn on the forehead of Hindu women. It is customarily worn by married women to symbolize their marriage and myth is that it protects them from the ‘bad eye’ of people (Mehta Products 2007).

Tribal markings

These are a form of tattooing where patterns are cut directly into the skin. They often hold religious significance or show membership of a particular tribe or group. They are deemed to be an essential feature of some cultures and are considered attractive in both males and females.

Piercing

There has been a huge increase in the popularity of body piercing. Ears, nose, navel, eyebrows and nipples have all been subject to this trend and have become fashion statements, particularly among teenagers and young adults

Skin adornments, particularly tattoos and body piercing, have implications for healthcare workers (see Evolve 15.2).

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

Problems affecting skin integrity are wide-ranging, varying from nappy rash to disfiguring wounds. The role of the nurse will differ according to the type and extent of the skin problem. For instance, when caring for an adult with a chronic skin condition such as atopic eczema, the focus of the nurse’s role will primarily be that of a health promoter, empowering the individual to manage and live with his or her condition.

The wide range of conditions and possible therapeutic interventions prohibit detailed discussion of every example. Instead, the following discussion focuses on a general assessment of skin, and then on one of the common problems of skin integrity, namely wounds.

ASSESSMENT OF THE SKIN

Assessment of the skin not only gives an indication of the condition of the skin itself, but can also help in identifying the client’s physical health, emotional state and lifestyle. Assessment requires close observation of the skin and includes visual inspection, palpation and noting skin odour. In addition, it is important to ask the client questions about his or her skin. Good illumination is necessary, and if there is any discharge from skin lesions, the nurse should wear disposable examination gloves. Above all, it is important that the nurse employs a sensitive approach and respects the dignity and privacy of the client. Holloway & Jones (2005) stress the need for a regular structured and systematic approach to skin assessments of clients.

Assessment of the skin should include observation of each of the following aspects of the skin:

• colour

• temperature

• moisture

• texture

• thickness

• turgor

• the presence of blemishes and lesions.

Colour and areas of discoloration

Skin colour varies between individuals, most obviously between people of different ethnic origins. There are several aspects of wound assessment and management that need to be addressed for patients with darkly pigmented skin (see Annotated Further Reading: Bethell 2005). There are also differences in skin colour in different parts of the body of each individual. Nipples and areolae of the breasts are darker than the rest of the skin, particularly in women during pregnancy. Similarly, areas that are exposed to sunlight, such as the face and arms, tend to be darker due to increased melanin concentration. These differences aside, and with the exception of older people in whom pigmentation can increase unevenly, skin colour is usually uniform.

An assessment of skin colour involves examining areas that are not generally exposed to sunlight, such as the palm of the hand. For the first few days of life the hands and feet of newborn babies are a bluish colour, termed acrocyanosis, due to inadequate peripheral vasculature. Assessment thereafter should involve looking for specific changes in skin colour, for instance:

• cyanosis (a bluish colour)

• pallor (a decrease of colour)

• jaundice (a yellow–orange colour)

• erythema (redness).

These changes in colour are most obvious in certain parts of the body. Cyanosis and pallor are particularly evident at the nail beds and buccal (mouth) mucosa. It is especially important to look at these areas in dark-skinned clients, as changes in general skin colour are less evident. Asian children may have Mongolian blue spots, which are very common and normal. The nurse should note any bruising. Although bruising can be normal, extensive or fingertip-type bruising can be a sign of abuse and should be investigated further, following agreed protocols.

Temperature

Feeling the client’s skin with the back of your hand best assesses skin temperature. The temperature of the skin increases or decreases with an increase or decrease in the circulation of blood through the dermis. Hands and feet are normally colder than the rest of the body when exposed to a cold environment due to reduced peripheral blood flow. Localized areas of increased or decreased temperature may indicate a problem. Hot, inflamed, red and painful skin surrounding a wound indicates the presence of infection. Similarly, if an unexposed limb is cold and pale, there may be circulatory impairment. When clients have had vascular surgery or a plaster cast or bandages applied to a limb, it is important to assess for skin changes that indicate impaired blood flow.

Moisture

Moisture refers to the wetness and oiliness of skin. It is related to the level of hydration and general condition of the skin. Normally the skin is smooth and dry except in the folds of the skin where it is moist. An increase in skin temperature arising from a hot environment or exercise is accompanied by perspiration, and is a normal phenomenon. However, when a client has a fever resulting from, for example, an infection, the skin may initially feel dry and hot but become damp from perspiration as the fever breaks. In older people dry skin, which is often accompanied by itchiness, can be a problem.

Texture

Usually the skin is smooth, soft and flexible, although in older people it sometimes becomes wrinkled and leathery. Skin thickness varies in different parts of the body: for example, skin is thickest on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Assess skin texture by stroking and palpating the skin with the fingertips; the nurse can gauge smoothness, thickness, suppleness and softness. Localized areas of changes to skin texture may indicate previous trauma or lesions. Should such changes be apparent, the nurse should ask the client about them. Rough and dry skin can also be due to exposure to cold weather or overwashing.

Turgor

Turgor refers to the elasticity of the skin, which is normally elastic and taut. It can be assessed by gentle pinching, lifting and letting go of an area of skin, usually on the back of the hand. Normally, the skin should quickly return to its former position. If it does not, it indicates that the client is dehydrated. However, some loss of skin elasticity is normal in older individuals. Excessive accumulation of fluid in the tissue – termed oedema – gives the skin a taut shiny appearance. It results from either direct trauma to the skin or an underlying condition. The presence of oedema increases susceptibility to further skin damage and delays wound healing.

Blemishes and lesions

Many skin blemishes and lesions are normal, for instance birthmarks, moles and freckles, and minor cuts, abrasions and blisters. Equally, nappy rash and heat rash are common among babies and children and mild acne is not uncommon in adults. Other blemishes and lesions, however, require further investigation and it may be necessary to refer the client to a doctor. For example, changes in an existing mole may indicate the development of a malignant melanoma.

Rashes may be caused by infection, such as a postviral rash, chickenpox, meningitis and shingles, or an allergic response, for example to particular chemicals, food products or medication. Other lesions may arise from skin infestations such as scabies, as a result of accidental or intentional trauma to the skin, or as a result of skin disease such as psoriasis or eczema (see Evolve 15.3). When abnormal blemishes, including scars or lesions, are detected, their colour, size, location and specific characteristics and, where appropriate, distribution and grouping should be noted. Clients should be asked about such blemishes, in particular to determine their cause.

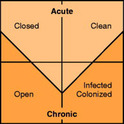

CLASSIFICATION OF WOUNDS

Wounds can be classified in a variety of different ways. They can be classified according to:

• cause (e.g. stab wound)

• status of skin integrity (e.g. open or closed wound)

• cleanliness of wound (e.g. presence or absence of infection or foreign bodies)

• the characteristics of the wound bed of open wounds

• extent of skin damage (e.g. full-thickness burn).

However, Westaby (1985) suggests that there are really only two types of wound:

• wounds characterized by skin loss

• wounds where there is no skin loss.

In practice, wound classification systems are often incomplete and overlap; for example, a surgically closed infected wound and an open, chronic, sloughy, bacterially contaminated wound. A simple wound classification system is given in Figure 15.4.

|

| Figure 15.4 |

Acute wounds result from surgery or accidents. However, in some instances acute wounds progress to chronic wounds as a result of complications. Acute surgical wounds tend to be surgically closed and clean while accidental wounds may be either clean or infected and can also be open or closed. Chronic wounds usually result from underlying diseases and tend to be open, as in the case of pressure ulcers and leg ulcers. Chronic wounds are more likely to be colonized or infected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree