Skin Care and Wound Prevention Strategies

During the past several decades, major advances have been made in the practice of skin and wound care. Clinicians now closely monitor coordinated cellular and biochemical events that occur in skin and wound healing. Manufacturers of skin and wound care products are partnering with clinicians to identify materials that help manage simple and complex skin conditions and wounds. At the same time, standards for describing skin and wounds are being developed to help the clinician document skin and wound assessment. Now, more than ever before, a solid foundation of information exists to accelerate skin and wound healing. But despite these advances, the incidence and prevalence of chronic wounds—such as pressure ulcers, venous ulcers, and diabetic ulcers—in the United States has risen to epidemic proportions. (See Fast facts about chronic wounds, page 3.)

Chronic wounds can exact an emotional, physical, and financial toll on the patient and his caregivers. Frustration and confusion continue to arise among clinicians when trying to determine a wound management pathway for a wound or skin condition, when to change to a different type of dressing or drug, how to document the progress of the wound or skin appropriately, and how to track outcomes based on care practices. (See Appendix E for more on best practices.)

Some solutions to these dilemmas can be found by understanding the delicate balance of art and science. Art refers to the team member’s skill and application technique in using the preferred management modality for skin and wound care. Science refers to the team member’s knowledge and understanding of the disease and of the preferred modality used in managing the patient’s care. Art and science —the fundamental tools of skin and wound healing—directly affect clinical and financial outcomes for the patient.

Still, after decades of published clinical practice guidelines, research results, and documented best practices for skin and wound care, not to mention the advances in knowledge and available technology, one has to ask: Why are there so many chronic, nonhealing wounds?

Reviewing the fundamentals of skin and wound care will help you answer this question. A complete understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the skin, the phases of healing, the types of wounds, and the options for wound repair is essential for recognizing factors that may complicate or delay wound healing. Each consideration plays a key role in assessing and managing wounds of all types.

SKIN STRUCTURE

The skin is the body’s largest organ, making up about 10% of our total body weight. The skin surface of an average adult covers about 2 square yards. Every day our skin is exposed to physical and mechanical assaults, which may or may not have permanent consequences.

Fast facts about chronic wounds | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

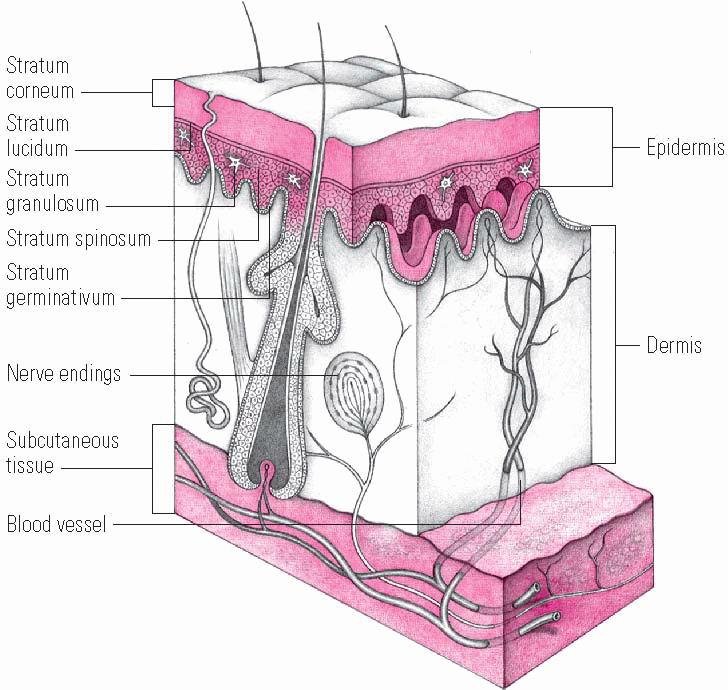

The skin is made up of two major layers—the epidermis and the dermis. Each layer is composed of different types of tissue and has different functions. (See Layers of the skin, page 4.) The dermis provides strength, support, blood, and oxygen to the epidermis.

Epidermis

The epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin and covered with epidermal cells, is thin and avascular, normally regenerating every 4 to 6 weeks. Its functions are to maintain skin integrity, to provide a physical barrier against assault by microorganisms and the environment, and to maintain hydration by holding in moisture.

The epidermis may be divided into the following strata, or sublayers:

Stratum corneum (horny layer). This outermost layer of the skin is composed of closely packed, flattened, polyhedral cells. This critical layer serves as the waterproof barrier of the epidermis and protects again infectious microorganisms, harsh chemicals, dirt, and environmental pollutants.

Stratum lucidum. This layer is a translucent line of cells found only on the palms and soles.

Stratum granulosum (granular layer). This layer, two to three cells thick, contains select keratinocytes.

Stratum spinosum. This layer is composed of keratinocytes that become larger, flatter, and contain less water as they travel to the surface of the skin.

Stratum germinativum-stratum basale (basal layer). This innermost layer of the skin contains basal keratinocytes that grow and continually divide, differentiating into the other layers of the epidermis over time. These cells ultimately flatten and lose their nuclei, thereby forming the stratum corneum and eventually replacing select cells that migrate to the skin surface and are lost. Keratinocytes of the basal layer are anchored to the basement membrane zone, which in turn is anchored to the second, thicker layer of the skin, the dermis.

Layers of the skin

The skin is composed of two fused layers—the epidermis and dermis. As this illustration shows, the epidermis has five strata—stratum corneum, stratum lucidum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum germinativum. Subcutaneous tissue, found beneath the dermis, is a loose connective tissue that attaches the skin to underlying structures.

|

The epidermis also contains melanocytes, which produce pigment, and Langerhans cells, which help the body respond to and process foreign antigens that penetrate the skin surface.

The outer layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, plays a key role in hydration. This layer is similar to a brick-and-mortar structure. The keratinocytes (the “bricks”) are held together by lipids and proteins (the “mortar”). The epidermis produces the lipids—oily substances that limit the passage of water into or out of the skin—which include cholesterol, ceramide, and fatty acids. If the barrier is deficient in these lipids, moisture can escape. With the loss of water, scales and cracks can develop on the stratum corneum, resulting in dry, flaky, itchy skin.

If the barrier integrity of the skin is altered, epidermal lipid synthesis increases. Cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis is increased first, followed by ceramide

synthesis. This process may be regulated in part by transepidermal water loss (TEWL), which is commonly used to measure the rate of passive diffusion of water from inside the body, through the stratum corneum, and into the external environment.

synthesis. This process may be regulated in part by transepidermal water loss (TEWL), which is commonly used to measure the rate of passive diffusion of water from inside the body, through the stratum corneum, and into the external environment.

Healthy skin structure is evident when the epidermis is intact. The substance that helps to maintain an intact epidermis is called natural moisturizing factor (NMF). NMF can absorb water, so it helps to hydrate skin cells. It’s found in the cells in the stratum corneum and is made of the breakdown products of proteins. NMF helps prevent individual skin cells from losing water and creates the smooth, nonflaky appearance of healthy, intact skin.

Dermis

The dermis contains blood vessels, hair follicles, lymphatic vessels, sebaceous glands, and eccrine (sweat) and apocrine (scent) glands. It’s composed of fibroblasts, which form collagen, ground substance, elastin, and other extracellular matrix proteins. Ground substance, an amorphous substance composed of water, electrolytes, plasma proteins, and mucopolysaccharides, fills the space between cells and the fibrous components, making the dermis turgid. Collagen fibers, the major structural proteins of the body, give skin its strength. Elastin is responsible for skin recoil or resiliency. Thick bundles of collagen anchor the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue and underlying supporting structures, such as fascia, muscle, and bone.

Subcutaneous tissue

The subcutaneous tissue is composed of adipose and connective tissue, as well as major blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. The thickness of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue varies from person to person and from one part of the body to another.

SKIN FUNCTION

The skin has six functions:

Protection. Skin acts as a physical barrier to microorganisms and other foreign matter, protecting the body against infection and excessive loss of fluids. The outer layer (stratum corneum) is slightly acidic, creating resistance to pathogenic organisms.

Sensation. Nerve endings of the skin allow us to feel pain, pressure, heat, and cold.

Thermoregulation. Skin regulates body temperature through vasoconstriction, vasodilation, sweating, and excretion of certain waste products, such as electrolytes and water.

Metabolism. Synthesis of vitamin D in skin exposed to sunlight activates the metabolism of calcium and phosphate, minerals that play an important role in bone formation.

Body image. The skin performs important body image roles with regard to appearance (cosmetic), individual attributes (identification), and ability to convey meaning through expression (communication).

Immune processing. The skin is a portal to the immune system with resident immune cells in both the epidermis (Langerhans cells) and the dermis (dermal dendritic cells).

Skin pH: Essential to function

The skin’s pH is acidic, ranging from about 4.2 to 5.6, depending on the area of the body and whether or not the skin is occluded. Skin should be kept in the acidic pH range for several reasons. After an injury to the skin, its barrier function recovers faster when the skin pH is more acidic, rather than more alkaline (less acidic). An acidic environment prevents premature desquamation, or shedding, of dead skin cells. Also, people with an acidic skin pH have less of a tendency toward sensitive skin, which is typically more alkaline.

The pH of the skin helps regulate some of the functions of the stratum corneum, including its permeability, defense against bacteria and fungi, and the integrity and cohesion of skin cells. Skin flora, or the microorganisms that live on or infect the skin, grow differently based on the skin pH. Normal flora grow better at an acidic pH, whereas pathogenic organisms, such as staphylococci, streptococci, and yeast, grow better at a neutral pH. Skin products with a higher pH are thought to promote bacterial growth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree