INTRODUCTION

Sexuality is an essential element of people’s lives and health. This chapter explores the nature of sexuality and how nurses can incorporate it in their day-to-day work. Nursing theory has acknowledged the significance of human sexuality, but it is an aspect of practice that some nurses have great difficulty with. This is probably due to two factors:

• firstly, sexuality is not easy to define

• secondly, it includes aspects of people’s lives that usually remain private.

Sexuality is a delicate subject, surrounded by mystery and misunderstandings, and consequently can be avoided by nurses and clients. The aim of this chapter therefore is to explore the meanings of sexuality and identify its relevance for nursing practice.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

The chapter begins by exploring definitions and meanings of sexuality. It includes an overview of the historical context and identifies some of the problems associated with understanding images of sexuality in the past. Masculinity, femininity and gender roles are then addressed, leading into an outline of the processes involved in the development of an individual’s sexuality. This includes information on the male and female reproductive systems and the biological control of human sexual development and the human sexual response. It also includes psychosocial theory related to the development of sexual identity and gender roles.

Following this is an overview of sexual norms and a summary of key research on sexual behaviour in Britain. This ends with a consideration of the relationship between emotion and sexual behaviour.

Care delivery knowledge

Care delivery knowledge begins with an outline of sexuality as an aspect of nursing models and moves on to discuss the assessment of an individual’s sexual health and sexuality related problems. It includes guidance on how to discuss sensitive issues with clients. To conclude this section, types of sexuality related problems are identified with appropriate nursing actions.

Professional and ethical knowledge

This section discusses the importance of nursing as a mainly female profession and identifies issues specific to the four branches of nursing. It includes an overview of legal issues and health policy related to sexuality.

Personal and reflective knowledge

This section comprises four case studies (p. 383), one for each branch of nursing. The case studies help to raise important issues for clinical practice and there are a number of questions to stimulate debate. You may like to read one of these before beginning this chapter, to use as a focus for reflection. After the case studies there are a number of exercises to help you develop your personal portfolio. The exercises encourage you to reflect on and learn from practice.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

DEFINING SEXUALITY

Defining sexuality is not easy. Sexuality is a social construct, and open to change and interpretation. Consequently, complete and accurate definitions cannot exist as they are moulded by cultural norms. However, most address the following issues:

• sex

• sexual orientation

• gender and associated roles

• relationships

• self-image

• self-esteem

• human attraction

• love.

To understand sexuality it is essential to take into account its changing nature and the social and historical forces that shape it. Indeed, the World Health Organization (2002) offers the following as a working definition

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human throughout life and encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles and relationships. While sexuality can include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, ethical, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.

Note how the last part of this definition emphasizes the varying nature of sexuality and how the society in which we live has a massive impact on how sexuality is expressed.

Studies on the history of sexuality emphasize how people’s attitudes and behaviour have changed (Foucault 1979). They are difficult to appreciate though, as comparisons of sexuality throughout the ages are based on today’s norms. For example, a popular image of Roman life emphasizes overindulgence, particularly in sexual activity. Victorian times on the other hand are characterized by a repressed attitude towards sexuality, surrounded by taboos, and managed through strict social etiquette. More recently, possibly associated with the availability of effective contraception, the 1960s become notorious for ‘free love’ and liberated youth.

Although there may be some truth in these stereotypes they are generalizations and focus on sexual activity rather than a broader understanding of sexuality. In turn, they have inherent dangers. First, they may be inaccurate due to the passage of time and the tendency for some ideas to achieve mythological status. Secondly, they focus on certain social classes in history and ignore the behaviour and attitudes of most of the population. Finally there is an assumption that a person’s sexuality develops during his or her ‘formative’ years and remains stable.

Focusing on recent history, understanding of sexuality based on stereotypes can influence the way we view older people. For example the 1930s and 1940s conjure up images of marriage for life, sexual faithfulness in the nuclear family, and sex as a taboo subject. Although more myth than reality, these images can influence the way a nurse cares for an older patient by making assumptions that people born in the 1930s and 40s acquired these norms and values, and even if they did, that they still hold the same norms and values today. Using these assumptions to guide practice then, a nurse may then not consider safer sex an appropriate topic to discuss with a 75-year-old person.

An important development in the recent history of sexuality though is the increasing acceptance of sexual activity as a valid topic for scientific study. This reflects more openness in society and the need to focus attention on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY

Descriptions of masculinity and femininity are associated with stereotypical images of males and females. These can be seen in films, cartoons and popular magazines and although they can be the butt of jokes, they can also be ideals or sources of aspiration. It could be argued that these stereotypes are outdated and that being masculine today encompasses the more feminine caring characteristics of the so-called ‘new man’ (although it could also be argued that the ‘new man’ is a myth and traditional gender differences and inequalities still exist). Similarly, the experience of being a woman has changed as many women take on paid employment, altering the traditional family life (Giddens 2005). Whatever the case, images of masculinity and femininity influence people in their day-to-day lives through their choice of jobs, the clothes they wear and the types of interests they develop.

Gender roles

The distinction between men’s and women’s roles in society can often be seen by the type of employment they take, and the social pressures influencing the decisions around their selection. From an early age children have ideas about what they would like to be when they ‘grow up’. With responses like ‘I want to be a train driver’ or ‘I want to be a nurse’ you can guess with some confidence the gender of the child. Although children’s aspirations differ from one society to the next, and from one generation to the other, boys’ views of their future will clearly contrast with those of girls. Of course these childhood wishes are unlikely to come true for many, but nevertheless, adult roles are largely gender-specific and comply with general expectations. There are, of course, exceptions; but being exceptions, they tend to reinforce the rule. For example, a female bricklayer and a male secretary will probably be seen as unusual, and may even acquire local celebrity status.

Gender role differences are also evident in leisure interests, household tasks and the relationships and interactions within a family. This can lead to gender associated disadvantage and in the 1970s Gove & Tudor (1972) found that marriage affected men’s health more positively than women’s (married men were healthier than single men whereas married women were less healthy than single women). Family structures, the nature of marriages and partnerships and employment patterns have changed significantly since the early 1970s though and evidence on the links between marital status and health is now less clear (Arber 1997).

Gender associated roles, particularly those arising from paid employment and within a family, enable people to express their sexuality to those around them and develop a positive self-image. Sometimes these roles are associated with immense pressures though, leading to role strain; i.e. the individual finds it difficult to wear too many hats. This is associated with role conflict which occurs when the demands arising from different roles become incompatible. For example, a woman can be a mother and be expected to make decisions regarding her children. She can also be a daughter and be expected to take advice from and listen to the wisdom of her parents. Such pressures can make the fulfilment of these roles difficult or impossible at times.

Make a list of the different roles you currently take.

• Are there any competing pressures between these roles?

• How might these roles change in the future?

• What would happen if you suddenly had a big, unexpected demand from one of your role obligations?

• Devise a plan to balance between your obligations for each role with your available resources.

(You might find the time planning exercise in Ch. 9 on relaxation and stress useful here.)

DEVELOPMENT OF AN INDIVIDUAL’S SEXUALITY

The reproductive system

For the first few weeks after fertilization the embryonic internal and external genitalia for males and females are the same. At about the seventh week hormonal changes lead to sex differentiation and the male reproductive system develops under the influence of increased androgen levels.

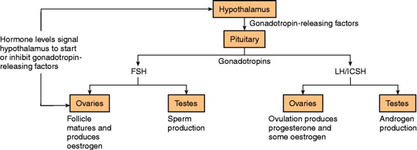

In childhood, the greatest time of physical change related to sexuality occurs during puberty. These are controlled hormonally and in Western society the process usually begins at around 11–12 years of age for girls and 12–13 years of age for boys. It involves the development of fully functioning reproductive systems and the body changes that result in the characteristic adult male and female physiques (Fig. 16.1).

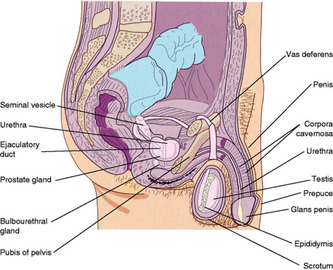

Adult male reproductive system (Fig. 16.2)

Testes

The testes have two functions:

• production of sperm

• secretion of testosterone.

|

| Figure 16.2 |

Testosterone is a hormone secreted by the testes and is needed for spermatogenesis and the sex drive. It is also responsible for the development of the following male secondary sex characteristics:

• enlargement of the penis and testes

• enlargement of the larynx producing a deeper voice

• growth of facial hair and pubic hair

• increased sebaceous gland activity

• muscle development.

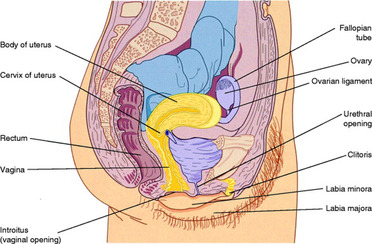

Adult female reproductive system

Internal genitalia

The ovaries (Fig. 16.3) have two functions:

• production of ova

• secretion of progesterone and oestrogen.

|

| Figure 16.3 |

Each ovary contains many oocytes. These are the cells that undergo a series of changes to develop into mature graafian follicles. Ovulation occurs when a follicle ruptures and releases an oocyte into the fallopian tube. This happens once a month during the menstrual cycle.

The hormone progesterone ‘prepares’ the woman’s body for pregnancy. It increases the growth of the endometrium and breasts and influences cervical mucus production and uterine muscle activity. The hormone oestrogen influences oogenesis and follicle maturation, the onset of puberty and the development of female secondary sex characteristics, and the growth and maintenance of reproductive organs. Female secondary sex characteristics include:

• growth and development of breasts

• body hair, e.g. pubic hair

• changes in fat distribution to produce the female physique

• vaginal secretions.

The fallopian tubes extend from the uterus towards the ovaries and open into the peritoneal cavity with funnel-like projections. In reproduction, the oocyte moves into the first part of the fallopian tube and is fertilized in the ampulla partway along its length. Peristalsis and ciliated cells help the oocyte move to the uterus, which is a hollow, thick-walled muscular structure that assists in the implantation of the embryo, nurtures the developing foetus and moves the baby out through the vagina at birth.

The epithelial layer is the endometrium and this changes in thickness and structure, under hormonal control, during the menstrual cycle. The cervix is at the lower end of the uterus.

The vagina connects the cervix to the external genitalia. It expands during childbirth and intercourse and has an acidic environment to protect it from pathogenic organisms. It becomes lubricated during sexual arousal with secretions from the vestibular glands and the vaginal walls. The distal end of the vaginal orifice is partially occluded by the hymen, which usually ruptures during first intercourse, but it can also be ruptured by tampons or exercise.

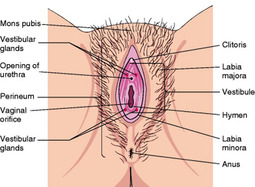

External genitalia (Fig. 16.4)

The mons pubis is a fatty pad over the pubic bone. The labia majora are covered in skin and have many sebaceous glands and the labia minora meet at the anterior end at the clitoris. The clitoris is rich in nerve endings and plays an important part in the sexual response. The vestibular glands secrete a fluid which lubricates the vagina during sexual arousal.

|

| Figure 16.4 (from Montague et al 2005, with kind permission of Elsevier). |

The menstrual cycle

This is controlled by the level of circulating hormones (oestrogen, progesterone, follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone) but can also be influenced by emotional factors. It has three phases:

1 The proliferative phase: oestrogen causes cell proliferation in the uterus, the endometrium thickens and the cervical mucus becomes thinner and more profuse, which ends with ovulation.

2 The secretory phase: vascularity of the endometrium increases under the influence of progesterone and the cervical mucus thickens to block the cervical canal. Hormonal secretion from the corpus luteum declines if fertilization does not take place and the endometrium begins to degenerate.

3 The menstrual phase: the flow of blood and endometrial tissue, which lasts 3–6 days. Prostaglandins stimulate the uterus to contract and this causes the characteristic pain (dysmenorrhoea).

Premenstrual syndrome

Before the menstrual phase some women experience a range of symptoms. Pelvic congestion and overall body water retention can give a feeling of distension. Tiredness, irritability, depression and loss of concentration are common and the increase in body weight alongside these symptoms can initiate changes in body image and low self-esteem. The reasons for these symptoms are unclear. Some theories suggest fluid retention is the cause, others that a deficiency of vitamin B6, resulting from hormonal variations, affects brain functioning leading to mood changes.

The intensity of the premenstrual syndrome varies from individual to individual, but does not seem to be linked to the degree of hormonal change. Also, the significance and character of premenstrual changes have varied throughout history. This suggests that the premenstrual syndrome is influenced by social, psychological as well as biological factors (Obermeyer 2000).

Menopause

Some changes in the sexual response for women are associated with the menopause. Usually occurring between the ages of 45 and 55, it is the time when the ovaries cease to function and a woman’s reproductive life ends. The reduced levels of oestrogen and progesterone are associated with a range of symptoms such as sweating, hot flushes, insomnia, depression, fatigue and headaches. Evidence to attribute these symptoms solely to hormonal changes is inconclusive though (Obermeyer 2000), as coming to terms with the end of a reproductive life plus other stressful life events commonly experienced at this age might also contribute. It is important to stress that the hormonal changes occurring during the menopause do not directly affect a woman’s interest in sex. Oestrogen levels do not control sex drive nor do they affect a woman’s ability to enjoy sex or have orgasms.

The ‘mid-life crisis’ in men

Men at this time of life often experience a slow decline in testosterone production. This results in less firm erections, less frequent ejaculations and a longer refractory period (see below). Men can also experience social and psychological pressures leading to a ‘mid-life crisis’ (Lachman 2004). However, in the same way that it is difficult to attribute menopause purely to biological factors, any changes in a man’s sexual activity at this time of life cannot always be associated with decreasing androgen levels.

THE SEXUAL RESPONSE

The sexual response in men and women is controlled by complex interactions between the central nervous system, the peripheral nervous system, neurotransmitters, hormones and the circulatory system (Engenderhealth 2005). It has five stages:

1 Desire. We can respond to a variety of stimuli, including sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. Based on thoughts, feelings, and experiences, these create sexual desire.

3 Plateau. In men this is associated with an increase in secretions from the urethral Cowper’s glands and an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and muscle tone. In women it is associated with retraction of the clitoris against the pubic bone and increases in blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and muscle tone.

4 Orgasm. In men this is a rhythmical contraction of the perineal muscles, closure of the bladder neck and ejaculation. In women orgasm may be single or multiple and involves contractions of the perineal muscles, uterus and fallopian tubes. It is more common for women not to experience orgasm every time they engage in sexual activity than it is for men.

5 Resolution. This is when the physiological changes are reversed. There is also a refractory period, which is the resting time that must elapse before the next sexual response can be initiated (Masters & Johnson 1966).

The impact of age-related physiological changes on the sexual response

For men

Men may experience the following age-related changes:

• Arousal: erections may occur less frequently and more and longer direct stimulation of the penis is required to establish and maintain an erection.

• Plateau: may be prolonged and ejaculation more easily controlled.

• Orgasm: the number and force of contractions decrease, but the sensation may be equally satisfying.

• Resolution: the length of time between orgasm and the next possible erection increases.

For women

Reduced oestrogen levels result in thinning of the vaginal mucosa, replacement of breast tissue by fat and shrinking of the uterus. These may affect the sexual response in older women as follows:

• Arousal: longer direct clitoral stimulation may be required, the vaginal opening expands less and vaginal lubrication may be reduced to the extent that synthetic lubrication may be required.

• Plateau: sensation may alter due to a decrease in vasocongestion and a reduced tensing of the vagina.

• Orgasm: contractions may be fewer.

• Resolution: the clitoris loses its erection more rapidly, but the refractory period after orgasm does not seem to lengthen for women as it does for men.

From the information on the effects of ageing on the sexual response:

• Can you see any physiological reasons why sexual activity might have to stop for older people?

• Can you see any physiological reasons why older people might not enjoy sexual activity?

• What implications do your answers have for nurses working with older people?

SEXUAL IDENTITY

A number of sociologists and psychologists have attempted to explain how people develop a sexual identity. There is agreement among many that relationships and interactions with those close to us play an important part. Others emphasize the biological factors and believe that our genetic make-up determines our sexual identity. The key theories are outlined below.

Freud’s psychoanalytical theory

Freud’s (1923) psychoanalytical theory offered an explanation of why boys and girls grow up differently, and it has since been developed by many psychologists. Freud focused on five stages of development. At each stage he identified the way in which individuals learn to balance the satisfaction of the ‘libidinal’ or pleasure drive of Id against those of the restrictive Ego and Superego.

Oral stage: 0–18 months of age

Newborn infants are unable to do little more than suck and drink and this satisfies the libidinal drive. During this stage of life only Id is present in the personality. Superego and Ego have not yet developed. Consequently the infant becomes frustrated if his demands are not met immediately.

Anal stage: 18 months to 3 years of age

During this period restrictions are placed upon the child; nourishment is no longer available on demand and potty training begins. This frustrates Id and results in temper tantrums. Eventually, Ego develops and the child exerts control over Id by using the potty. It is at this time that the libidinal drive passes to the anus and the child finds control of bowel movements pleasurable, both by expelling the contents and by retaining them.

Phallic stage: 3–5 years of age

During the first two stages of development the infant is unaware of gender differences. All children are seen as ‘little males’. However, during the phallic stage the child becomes aware of its gender and discovers pleasure can be derived from either the penis or clitoris. The libidinal drive then focuses on this body area as the child derives satisfaction from playing with its sexual organ.

During this phase the child forms an incestuous desire for the parent of the opposite sex. In the male child this is called the Oedipus complex. Here the boy’s love for his mother becomes very intense making him very jealous of anyone competing for her attention, including his father. However, he has noticed that girls and his mother do not have a penis. He suspects this is because they were castrated as a punishment when they were younger and he fears that if he continues the feelings he has for his mother then his father will castrate him also. To protect his penis he represses his feelings for his mother and identifies with his father. This way he retains both his penis and, by identifying with his father, he fulfils the desire for his mother.

In the female child a different process, the Electra complex, occurs. Initially the she is drawn towards her mother. She discovers, however, that unlike her father and boys, she does not possess a penis. She assumes she has been castrated, for which she blames her mother, and feels inferior to males, a phenomenon called ‘penis envy’. Realizing she will not get a replacement penis, she replaces this desire with one for a baby, and she looks to her father to provide her with one. This brings problems though, as she will be in direct competition with her mother who she fears will reject her. To prevent this she internalizes the image of her mother as carer, so that her mother will continue to love her. This is the final part of the Electra complex, where the girl identifies again with her mother, and is called anaclytic identification.

The phallic stage is a very ambivalent time for a child of either gender and parental attitudes during this stage have profound ramifications on the child’s development.

Latency stage: 5 years of age to puberty

Following the traumas of the phallic stage, this period is relatively quiet. Sexual interests are replaced by school, playtimes, sports and a range of new activities. The child also meets people from outside the family and makes new relationships.

Genital stage: puberty to adulthood

With the onset of puberty the individual experiences intense libidinal drives to engage in full sexual activity. The capacity for full physiological sexual responses has developed by this stage and in turn, individuals are able to experience themselves as complete sexual beings. At this stage boys lose their sexual attachment for their mother, and girls for their father, allowing them to make other sexual attachments. However, during this stage, the individual has to learn to express sexual energy in socially acceptable ways.

Despite criticisms, Freud’s theory highlights the importance of relationships and interactions between children and the adults around them. The nature and quality of relationships during these formative years are significant in the development of an individual’s sexuality. In certain settings nurses will work with people who have problems with their identity. An identity crisis in a patient, in particular in their sense of sexuality, is likely to have its origins in childhood development, and advanced nursing practice may involve exploration of an individual’s relationships with their parents.

Neoanalytical theory

Some writers modified Freud’s ideas, basing their explanations of gender identity on other experiences in early childhood. Chodorow (1992) emphasizes the importance of the early maternal bond that exists in all societies. Girls never completely break this bond and their identity incorporates a significant relational element. Boys on the other hand have to break this bond in order to develop a masculine identity characterized by independence, individuality and a rejection of the feminine. As a result, women require a close relationship in order to maintain their self-esteem, but men feel threatened by such close emotional attachments.

Chodorow’s theory assumes a simplistic role of women as the main carer of children, especially in the early years, and has been criticized for failing to take into account other feelings, for example aggression and assertiveness. On the other hand it helps to make sense of some men’s apparent inability to express their emotions.

Sociobiological theories

Sociobiologists use ideas from evolutionary biology to explain human behaviour and sexual identity. Birkhead (2000) argues sexual behaviour is influenced by the biological need to reproduce. People strive to be successful in reproduction so genetic information can be passed on to the next generation. Men have many sperm so it makes sense for men to use as many as they can. This has been given as an explanation for men being more promiscuous than women. On the other hand, women have relatively few ova, and their owners need to make sure that they are used carefully. It is in the interests of women therefore to be selective as to whom they choose as a mate. They need to make sure that their genes are amalgamated with others of a high quality.

This theory has implications for attitude development. Men should approve of casual sex and have many partners, whereas women should be less approving of casual sex and seek long-term commitment from few partners. Related to this is the explanation of men’s jealousy and desire to control women’s sexuality. Because a man provides for the mother and child he needs to make sure that he is rearing his own offspring and not someone else’s. For this reason men would disapprove of their wives engaging in extramarital sex.

This sociobiological theory has its critics. Birkhead (2000) suggests that society is more complex than the picture painted here and sexual behaviour is more than purely reproductive. For example, the theory does not take into account the nature of sex and sexuality throughout an individual’s lifespan. Also it attempts to legitimize inequalities between men and women by suggesting they are natural and normal; failing to explore the importance of socialization and the use of power in establishing and maintaining gender inequalities.

Social learning theory

This is concerned with how boys and girls learn their gender-related roles (Connell 2002). It does not see biology as particularly important in determining behaviour, but emphasizes the associations and interactions between children and others. This is, in the first place, the communication that takes place with parents. Behaviour consistent with gender is reinforced through rewards. So when parents and others react in a positive way towards a girl in a pretty dress playing with dolls and an urchin of a boy climbing trees, this behaviour is likely to be repeated.

Children learn their behaviour from significant role models, and these include parents, siblings, teachers and people in the media. This means that learning how to behave as a woman or a man is only partly influenced by parental upbringing. It is the influence of people and images from outside the family that explains why children differ from their parents. This theory is dynamic and takes account of an individual’s changing nature and incorporates such things as trends and fashions. However, it tends to see people waiting to be moulded by the environment and those around them. In this sense, self-will, motivation and the ability to manipulate the environment are ignored.

Social learning theory attempts to explain how culture is learned; that is how individuals acquire certain patterns of beliefs, values, attitudes and norms. In turn, culture has a strong impact on sexuality and, of course, different cultures assign different meanings to sexuality. Some cultures emphasize equality between partners, including goals of mutual pleasure and psychological disclosure. Others believe that the exchange of pleasure, or communication of affection through sexual touching, plays no major role in the expression of sexuality (Monga & Lefebvre 1995). Some cultures permit premarital sex, while others condemn it. Culturally determined formal rituals can also play an important part in the development of a sexual identity, for example the circumcision of boys. Nurses therefore need an understanding of cultural differences so that they can give culture-specific care; within the bounds of what is legally and ethically acceptable (Jeffreys 2006).

NORMS

By learning from others and society, we acquire an understanding of what is ‘normal’. However, this process may lead to prejudicial attitudes towards individuals or groups. Norms are socially acceptable behaviours that help to define what is ‘right’ in society. Nevertheless, society is made up of a number of sub-groups which may have different norms of sexual behaviour, and these are a potential source of conflict. For example the norms of sexual behaviour held by the youth culture could be very different from those held by parents or by professionals. There is a possibility that parents, teachers, doctors and nurses will see their own ‘standards’ as right and begin to impose them on those who they feel they are responsible for. For nurses working in the area of sexual health promotion with teenagers this creates an ethical problem. Should they try and persuade young teenagers not to have sex or should they accept this as a fact and offer advice on safer sex? The former might frighten the teenager off and prevent them using services or seeking help. The latter might expose the teenager to a range of physical and psychological risks.

There are also inequalities in the way that norms are applied to groups within society. Certain behaviours may be viewed as acceptable for men but not for women, or acceptable for adults but not for teenagers. Similarly attitudes towards a stable heterosexual couple may differ from that towards a stable homosexual couple.

Homosexuality

The idea of an open homosexual identity, where people attracted to others of the same gender have their own culture and lifestyle, is a relatively new phenomenon. Gay bars, newspapers, associations and holidays have not existed overtly for very long.

In the past, individuals were not labelled with a sexual identity that described them as either heterosexual or homosexual. In Roman times, for example, it formed part of a range of experiences for some people. In modern times, this may also be seen in people who have relationships with either gender or, occurring as a result of a situation, i.e. those in single-sex restrictive institutions such as prisons, monastic orders and boarding schools.

Bancroft (1989) describes the development of a gay culture through history, noting varying periods of acceptance and repression of homosexual activity. In the recent history of developed countries homosexuality has been characterized by rejection though. This was seen in public attitudes and inequalities within the legal frameworks of many countries. Minority groups are used as scapegoats for things going wrong in society, and commonly homosexuals have been perceived as a minority group responsible for many ills within society, from the downfall of the Greek empire to the spread of the HIV virus.

Hostility towards homosexuality may be denial that a mixed sexual identity can exist. Arguments based on the ‘laws of nature’ that are frequently used to justify this stance (i.e. ‘Our bodies are not made for it’) assume sexual activity is used solely for procreation; where homosexuality has no function. However, acceptance of this argument also excludes all non-procreational heterosexual activity.

The medical profession in the 19th century gave a different interpretation of homosexuality: a sickness for which treatments were developed. Although during the 20th century medicine’s attitude towards homosexuality softened, the idea that it was something to treat remained and it was not until 1974 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of pathological diagnoses.

Female homosexuality is written about less frequently and has had a lower profile throughout history. This does not mean that women are less likely than men to be involved in homosexual activity, but is probably a reflection of the domination of women by men across a range of social institutions.

See the Evolve 16.1 web resource for a reflective exercise on sexual equality and a useful web link.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR

Because of its sensitive nature, investigating sexual behaviour has been particularly challenging for researchers. For example, the National Survey on Sexual Behaviour in Britain (Wellings et al 1994) had a difficult start because the Department of Health withdrew its backing at the last minute and researchers had to find alternative support. The impetus for the work came from the need to find out more about the relationship between sexual practices and the spread of HIV and AIDS, but the political sensitivity of the subject meant that the researchers had problems in starting. This is very similar to the experiences of Kinsey in the USA (Kinsey et al 1948) and Lanval (1950) in Belgium, who both suffered in their attempts to discover more about sexual behaviour. Their research was condemned as pornographic and unworthy of academic attention. Despite these problems Kinsey persisted, and interviewed over 10 000 people on what sexual practices were common. It was apparent from the findings that the incidence of homosexuality, masturbation and premarital intercourse, and the active role of women in sexuality, differed from the social norms of the time, and this caused considerable political disquiet (Gagnon & Simon 2005).

Returning to Wellings et al (1994), who published one of the most extensive studies on sexual behaviour in Britain: as it focused on how the spread of HIV might be related to certain sexual practices it concentrated on issues like unprotected sex, numbers of partners and types of activities involving risks, although because of its quantitative nature it tells little about the meaning of sexual experiences to individuals. It does, however, give details of who does what with whom, at what age and how often, and relates these sorts of things to class and educational level. One major drawbacks was its failure to include people over 60 years of age. This perhaps reflects the commonly held view that ‘older people don’t do that sort of thing’.

See Evolve 16.2 for more information on this research.

• Outline the findings of Wellings et al (1994) on sexual behaviour.

• Discuss contemporary heterosexual behaviour.

• Discuss contemporary homosexual behaviour.

• Understand sexual behaviour from a global perspective.

A similar survey was carried out in the UK to try and help understand the trends in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections and teenage pregnancies. The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles took place between 1999 and 2001 and was reported in three articles in The Lancet (Johnson et al 2001).

Though similar to Wellings et al (1994), the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Johnson et al 2001) was limited by only including people between 16 and 44. This excluded a small group of young teenagers and a very large group of people aged 45 and above. (See Evolve 16.3 material for more detailed findings.)

• Outline the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Johnson et al 2001).

• Compare the findings of Johnson et al (2001) with those of Wellings et al (1994).

Surveys on sexual behaviour are fraught with problems because of the sensitive nature of the topic. Findings from such surveys must be treated with caution because their accuracy and reliability may be influenced by individuals’ honesty and openness in their responses. Nevertheless, this kind of research provides important information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree