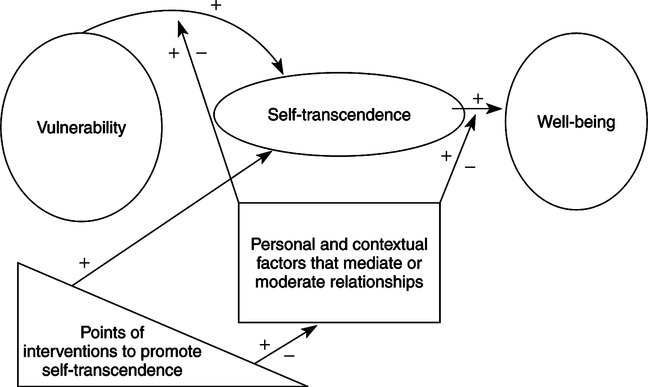

Reed (1991a) developed her theory of selftranscendence using the strategy of “deductive reformulation.” This strategy, among other theory development approaches that deliberately utilize nursing models, originated with Reed’s professors, notably Ann Whall and Joyce Fitzpatrick of Wayne State University. (See Fitzpatrick, Whall, Johnston, & Floyd, 1982; Shearer & Reed, 2004; and Whall, 1986 for applications of this strategy.) Deductive reformulation in constructing middle range theory uses knowledge derived from non-nursing theory that is reformulated deductively from a nursing conceptual model. The primary non-nursing theory sources were life span theories on adult social-cognitive and transpersonal development (e.g., Alexander & Langner, 1990; Commons, Richards, & Armon, 1984; Wilber, 1980, 1981, 1990). Principles from life-span theories were reformulated using the nursing perspective of Martha E. Rogers’ conceptual system of unitary human beings (Rogers, 1970, 1980, 1990). Reed describes her theory as originating from three sources (Reed, 2003, 2008). The first source was the conceptualization of human development (Lerner, 2002) as a lifelong process that extended beyond the attainment of adulthood throughout the aging and dying processes. This emerging belief in the ongoing potential for development was a paradigm shift from previously held views that both physical growth and mental development ended at adolescence (Reed, 1983). The second source for the theory was the early work of nursing theorist Martha E. Rogers (Rogers, 1970, 1980, 1990). Rogers’ three principles of homeodynamics were congruent with the key principles of the evolving life span developmental theory. Rogers’ integrality principle identified development as a function of both human and contextual factors; it also identified disequilibrium between person and environment as an important trigger of development. Similarly, developmental theorist Riegel (1976) proposed that asynchrony in development among physical, emotional, environmental, and social dimensions was necessary for developmental progress. Rogers’ helicy principle characterized human development as innovative and unpredictable. This principle is similar to life span principles that identified development as nonlinear, continuous throughout the life span, and evident in variability within and across individuals and groups. Rogers’ resonancy principle described human development as a process of movement that, although unpredictable, had pattern and purpose. Life span theorists also proposed that the process of development displayed patterns of complexity and organization. Thus knowledge gained from the non-nursing life span developmental perspective was reformulated, using an appropriate nursing conceptual system. The third source for the theory was evidence from clinical experience and research indicating that clinically depressed older persons reported fewer developmental resources to sustain their sense of well-being in the face of decreased physical and cognitive abilities than did a matched group of mentally healthy older adults (Reed, 1986b). In addition, development in elderly and in “oldest-old” adults was found not be a linear process of gain and subsequent loss, but a process of transforming old perspectives and behaviors, and integrating new views and activities (Reed, 1989, 1991b). Self-transcendence theory was grounded in belief in the developmental nature of older adults and the necessity of continued development to maintain mental health and a sense of well-being during the process of aging (Reed, 1983). Therefore, the initial research in theory building was conducted with older adults (Reed, 1986b, 1989, 1991b). In the first study, Reed (1986b) examined patterns of developmental resources and depression over time in 28 mentally healthy and 28 clinically depressed older adults (mean age, 67.4 years). Levels of developmental resources were measured 3 times (6 weeks apart) with the 36-item Developmental Resources of Later Adulthood (DRLA) scale, previously developed and tested by Dr. Reed. The healthy adults perceived higher levels of resources across time than did the depressed adults. Scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1977) were significantly higher in depressed individuals across time than were those of the mentally healthy. Strong relationships between DRLA scores and subsequent CES-D scores indicated that developmental resources influenced mental health outcomes in the healthy group; the reverse relationship found in the depressed group indicated that depression negatively influenced developmental resources in terms of the ability to explore new outlooks on life, to share wisdom and experience with others, and to find spiritual meaning. In the second study, Reed (1989) explored the degree to which key developmental resources of later adulthood were related to mental health in 30 hospitalized clinically depressed older adults (mean age, 67 years). Participants completed the DRLA and CES-D measures and rated the importance in their current lives of each developmental resource reflected in the DRLA items. An inverse correlation was found between the level of resources and depression. Participants also reported that the resources represented by the DRLA items were highly important in their lives. In addition, key reasons given by participants for their psychiatric hospitalization were congruent with self-transcendence issues significant in later adulthood (e.g., physical health concerns, relationships with adult children, questions about life and death). During the initial DRLA instrument development and testing, a factor labeled transcendence accounted for 45.2% of the variance in DRLA scores. In the second study (Reed, 1989), the 15-item transcendence factor was also more highly correlated with the CES-D than was the entire DRLA. Therefore, a recommendation for future research was to examine further the psychometric properties of the instrument, with one goal being to shorten the DRLA to facilitate ease of administration in clinical settings. A third study explored patterns of selftranscendence and mental health in 55 independent-living elders (ranging in age from 80 to 97 years) (Reed, 1991b). In this study, self-transcendence was defined as “the expansion of one’s conceptual boundaries inwardly through introspective activities, outwardly through concerns about other’s welfare, and temporally by integrating perceptions of one’s past and future to enhance the present” (Reed, 1991b, p. 5). Self-transcendence was measured by the newly developed Self-Transcendence Scale (STS), derived from the previously identified transcendence factor in the original DRLA scale. The STS score was correlated inversely with both CES-D and Langner Scale of Mental Health Symptomatology (MHS) scores. The MHS is an index of general mental health on which higher scores indicate impairment in mental health in nonpsychiatric populations (Langner, 1962). In addition, the four patterns of self-transcendence identified by participants (generativity, introjectivity, temporal integration, and body-transcendence) were congruent with Reed’s definition of the concept. Early in her theoretical work, Reed (1986a, 1987) proposed a process model approach for constructing conceptual frameworks that would guide nurses and nursing education in clinical specialties. In that model, health was proposed as the central concept, or axis, around which revolved nursing activity, person, and environment. The assumption of the model was that the focus of the nursing discipline was on building and engaging knowledge to promote health processes. Family, social networks, physical surroundings, and community resources were environments that significantly contributed to health processes that nurses influenced through “managing therapeutic interactions among people, objects, and [nursing] activities” (Reed, 1987, p. 26). In her initial explication of the emerging selftranscendence theory, Reed (1991a) identified one key assumption based on Rogers’ conceptual system. This assumption was that persons are open systems who impose conceptual boundaries upon themselves to define their reality and to provide a sense of wholeness and connectedness within themselves and their environment. Reed (2003) reaffirmed this assumption in a later publication, restating Rogers’ basic assumption that “human beings are integral with their environment” (p. 146). Self-conceptual boundaries fluctuate in form across the life span and are associated with human health and development. Self-transcendence was proposed as an important indicator of a person’s conceptual self-boundaries that could be assessed at specific times. A second assumption identified in the later description of the theory was that self-transcendence is a developmental imperative (Reed, 2003), that is, self-transcendence must be expressed like any other developmental capacity in life for a person to realize a continuing sense of wholeness and connectedness. This assumption is congruent with Frankl’s (1969) and Maslow’s (1971) conceptualizations of selftranscendence as an innate human characteristic that, when actualized, gives purpose and meaning to a person’s existence. There are three basic concepts in the theory of self-transcendence: vulnerability, self-transcendence, and well-being (Reed, 2003, 2008). Vulnerability is the awareness of personal mortality that arises with aging and other life phases, or during health events and life crises (Reed, 2003). Although vulnerability was not explicitly identified as a concept in Reed’s earlier writings, it was not a new idea. The concept of vulnerability clarifies that the context within which selftranscendence is realized is not only when confronting end-of-own-life issues but includes life crises such as disability, chronic illness, childbirth, and parenting. Self-transcendence refers to the fluctuations in perceived boundaries that extend persons beyond their immediate and constricted views of self and the world. The fluctuations are pandimensional: outward (toward awareness of others and the environment), inward (toward greater insight into one’s own beliefs, values, and dreams), temporal (toward integration of past and future in a way that enhances the relative present), and transpersonal (toward awareness of dimensions beyond the typically discernible world) (Reed, 1997b, 2003, 2008). Well-being means “feeling whole and healthy, in accord with one’s own criteria for wholeness and well-being” (Reed, 2003, p. 148). The second proposition of the theory is that conceptual boundaries are related to well-being (Reed, 1991a). Depending on their nature, fluctuations in conceptual boundaries influence well-being positively or negatively across the life-span. For example, an increase in self-transcendence views and behaviors is expected to be positively related to mental health as an indicator of well-being in persons confronting end-of-life issues. A specific example of a negative influence is that the inability to reach out for or to accept friendship would be expected to be related to depression as an indicator of mental health. Given the key assumption about the personenvironmental process (Reed, 1991a), a third set of propositions was identified by Reed in 2003. Personal and environmental factors function as correlates, moderators, or mediators of the relationships between vulnerability, self-transcendence, and well-being. In summary, the 2003 model of the selftranscendence theory proposes the following three sets of relationships (Figure 29-1): Reed’s empirical middle range theory was constructed using the strategy of deductive reformulation to enhance understanding of the end-of-life phenomenon of self-transcendence (Reed, 1991a). The logic used is primarily deduction, to ensure that the middle range theory was congruent with Rogerian and life span principles. Analogical reasoning was also used to work from other theories of life span development, drawing comparisons between psychology and nursing about human development and potential for well-being at all phases of life. The key concepts of the theory are related in a clear and logical manner, while still allowing for creativity in the way the theory is applied, tested, and further developed. Reed’s strategy of constructing a nursing theory—from non-nursing theories, a nursing conceptual model, research, and clinical and personal experiences—piqued nurses’ interest in this phenomenon of developmental maturity and provided impetus for further theorizing and research into the variety of situations in which awareness of personal mortality occurs. The quest for nursing is to facilitate human well-being through what Reed called “nursing processes,” of which self-transcendence is one example (Reed, 1997a). Toward this end, self-transcendence theory has been used in practice, education, and research. Reed’s (1986a, 1987) process model for clinical specialty education and psychiatric–mental health nursing practice articulated the relationships between the metaparadigm constructs of health, persons and their environments, and nursing activity. Self-transcendence theory delineates specific concepts derived from process model constructs of health (i.e., well-being), person (i.e., self-transcendence), and environment (i.e., vulnerability) and proposes relationships among those concepts to provide direction for nursing activities. Reed (1991a) and Coward and Reed (1996) suggested a variety of nursing activities that facilitate expansion of self-conceptual boundaries—journaling, meditation, life review, and religious expression, to name a few. Self-transcendence may be integral to healing in many life situations. Nurse activities that promote the perspectives and activities of self-reflection, altruism, hope, and faith in vulnerable persons are associated with an increased sense of well-being. Group psychotherapy (Stinson & Kirk, 2006; Young & Reed, 1995) and breast cancer support groups (Coward, 1998, 2003; Coward & Kahn 2004; 2005) are interventions that nurse researchers have used to provide clients with opportunity for examining their values, for reaching out to share experience with and help similar others, and for finding meaning from their health situations. Others have suggested similar strategies to facilitate well-being in caregivers of persons with dementia (Acton & Wright, 2000) and in bereaved individuals (Joffrion & Douglas, 1994). Acton and Wright (2000) suggest arranging respite care for caregivers so that they have time and energy for transpersonal activities. McGee (2000) suggests that recovery in alcoholism involves a process of self-transcendence, as facilitated by a nurse-designed environment that supports the 12 steps and 12 traditions of Alcoholics Anonymous. Walsh and her students are using applications of creative art therapy to promote self-transcendence in nursing students and long-term care residents (Chen & Walsh, 2009). Themes of self-transcendence are found in the writings of nurse theorists influential in nursing education. Sarter (1988) analyzed the philosophical roots of four contemporary nursing theories (Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings, 1970, 1980; Newman’s theory of expanding consciousness, 1986; Watson’s theory of caring, 1979, 1985; and Parse’s theory of man-living-health, 1981). These theories share a common view in identifying self-transcendence as an appropriate philosophical foundation for the discipline. Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory, which contains concepts similar to self-transcendence that are associated with development and health, guides the curricula of several undergraduate programs (Erickson, 2002; Erickson, Tomlin, & Swain, 1983). Reed describes self-transcendence as “both a human capacity and a human struggle that can be facilitated by nursing” (Reed, 1996, p. 3). Reed (1997a) went on to define nursing succinctly as “an inherent human process of well-being, manifested by complexity and integration” (p. 76), with self-transcendence as an important factor in the process of well-being. Given this link between well-being and self-transcendence, it seems imperative that nurses be educated to understand and to promote self-transcendence views and behaviors in their clients. Self-transcendence is also a pathway for helping the healer, or healing the healer, so that nurses themselves maintain a healthy lifestyle as they care for others (Conti-O’Hare, 2002). A large number of research studies provide evidence that supports the association between self-transcendence and increased well-being in populations that typically are confronted with an awareness of their own personal mortality. The initial research studies relating self-transcendence to depression were conducted with elders (Reed, 1986b, 1989, 1991a). More recent research reported similar relationships in depressed older adults (Klaas, 1998; Stinson & Kirk, 2006; Young & Reed, 1995), middle-aged adults (Ellermann & Reed, 2001), and individuals who lost loved ones from HIV/AIDS (Kausch & Amer, 2007). Buchanan, Ferran, and Clark (1995) examined self-transcendence and suicidal thought in older adults. Upchurch (1993, 1999) and Upchurch & Mueller (2005) explored the relationship between self-transcendence and activities of daily living in non-institutionalized older adults. Two studies explored self-transcendence and elders’ perceptions of positive physical and mental health (Bickerstaff, Grasser, & McCabe, 2005; Nygren et al., 2005). Walton, Shultz, Beck, and Walls (1991) identified an inverse relationship between self-transcendence and loneliness in healthy older adults. Decker and Reed (2005) found that integrated moral reasoning, completion of a living will, and prior experience with a life-threatening illness, but not level of self-transcendence, were related to elders’ desire for less aggressive treatment at end-of-life. An impressive number of studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between selftranscendence and well-being or quality of life in persons with HIV or AIDS (Coward, 1994, 1995; Coward & Lewis, 1993; McCormick, Holder, Wetsel, & Cawthon, 2001; Mellors, Erlen, Coontz, & Lucke, 2001; Mellors, Riley, & Erlen, 1997; Stevens, 1999). Several studies have described self-transcendence or related concepts in women with breast cancer (Carpenter, Brockopp, & Andrykowski, 1999; Coward, 1990a, 1990b, 1991; Coward & Kahn, 2004, 2005; Kamienski, 1997; Kinney, 1996; Matthews, 2000; Pelusi, 1997; Taylor, 2000). The positive effect of a self-transcendence theory–based cancer support group intervention on self-transcendence and well-being in newly diagnosed women also was documented by Coward (1998, 2003). Self-transcendence in caregivers of persons with dementia was explored by Acton (2003) and Acton & Wright (2000) and was studied in caregivers of terminally ill patients who had died within the previous year (Enyert & Burman, 1999; Reed & Rousseau, 2007). Other populations studied include healthy middle-aged adults (Coward, 1996), elderly men with prostate cancer (Chin-A-Loy & Fernsler, 1998), female nursing students and faculty (Kilpatrick, 2002), nurses (Hunnibell, 2006; McGee, 2004); homeless adults (Runquist & Reed, 2007), elders with chronic heart failure (Gusick, 2005), and liver transplant recipients (Bean & Wagner, 2006; Wright, 2003). Other studies reported positive relationships between transcendence and transformation and finding meaning among elders (Klaas, 1998) and women with rheumatoid arthritis (Neill, 2002).

Self-Transcendence Theory

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

Environment

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

LOGICAL FORM

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

Education

Research

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access