1 Scope of Critical Care Practice

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• describe the history and development of critical care nursing practice, education and professional activities

• discuss the influences on the development of critical care nursing as a discipline and the professional development of individual nurses

• outline the various roles available to nurses within critical care areas or in outreach services

• discuss the potential impact of clinical decision-making processes on patient outcomes

• consider processes in the work and professional environment that are influenced by local leadership styles.

Introduction

There is unprecedented demand for critical care services globally. In our region, there are approximately 119,000 admissions to 141 general intensive care units (ICUs) in Australia per year; this includes 5500 patient re-admissions during the same hospital episode. In New Zealand, there are 18,000 admissions per year to 26 ICUs, including 500 re-admissions.1 Patients admitted to coronary care, paediatric or other specialty units not classified as a general ICU are not included in these figures, so the overall clinical activity for ‘critical care’ is much higher (e.g. there were also 5500 paediatric admissions to PICUs).1 Importantly, critical care treatment is a high-expense component of hospital care; one conservative estimate of cost exceeded $A2600 per day, with more than two-thirds going to staff costs, one fifth to clinical consumables and the rest to clinical support and capital expenditure.2

Critical care as a specialty in nursing has developed over the last 30 years.3,4 Importantly, development of our specialty in Australia and New Zealand has been in concert with development of intensive care medicine as a defined clinical specialty. Critical care nursing is defined by the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses as:

Specialised nursing care of critically ill patients who have manifest or potential disturbances of vital organ functions. Critical care nursing means assisting, supporting and restoring the patient towards health, or to ease the patient’s pain and to prepare them for a dignified death. The aim of critical care nursing is to establish a therapeutic relationship with patients and their relatives and to empower the individuals’ physical, psychological, sociological, cultural and spiritual capabilities by preventive, curative and rehabilitative interventions.5

Critically ill patients are those at high risk of actual or potential life-threatening health problems.6 Care of the critically ill can occur in a number of different locations in hospitals. In Australia and New Zealand, critical care is generally considered a broad term, incorporating subspecialty areas of emergency, coronary care, high-dependency, cardiothoracic, paediatric and general intensive care units.7

Development of Critical Care Nursing

Critical care as a specialty emerged in the 1950s and 1960s in Australasia, North America, Europe and South Africa.4,8–11 During these early stages, critical care consisted primarily of coronary care units for the care of cardiology patients, cardiothoracic units for the care of postoperative patients, and general intensive care units for the care of patients with respiratory compromise. Later developments in renal, metabolic and neurological management led to the principles and context of critical care that exist today.

Development of critical care nursing was characterised by a number of features,4 including:

• the development of a new, comprehensive partnership between nursing and medical clinicians

• the collective experience of a steep learning curve for nursing and medical staff

• the courage to work in an unfamiliar setting, caring for patients who were extremely sick – a role that required development of higher levels of competence and practice

• a high demand for education specific to critical care practice, which was initially difficult to meet owing to the absence of experienced nurses in the specialty

• the development of technology such as mechanical ventilators, cardiac monitors, pacemakers defibrillators, dialysers, intra-aortic balloon pumps and cardiac assist devices, which prompted development of additional knowledge and skills.

There was also recognition that improving patient outcomes through optimal use of this technology was linked to nurses’ skills and staffing levels.12 The role of adequately educated and experienced nurses in these units was recognised as essential from an early stage,8 and led to the development of the nursing specialty of critical care. Although not initially accepted, nursing expertise, ability to observe patients and appropriate nursing intensity are now considered essential elements of critical care.12

Critical Care Nursing Education

Appropriate preparation of specialist critical care nurses is a vital component in providing quality care to patients and their families.5 A central tenet within this framework of preparation is the formalised education of nurses to practise in critical care areas.13 Formal education – in conjunction with experiential learning, continuing professional development and training, and reflective clinical practice – is required to develop competence in critical care nursing. The knowledge, skills and attitude necessary for quality critical care nursing practice have been articulated in competency statements in many countries.14–16

Critical care nursing education developed in unison with the advent of specialist critical care units. Initially, this consisted of ad-hoc training developed and delivered in the work setting, with nurses and medical officers learning together. For example, medical staff brought expertise in physiology, pathophysiology and interpretation of electrocardiographic rhythm strips, while nurses brought expertise in patient care and how patients behaved and responded to treatment.12,17 Training was, however, fragmented and ‘fitted in’ around ward staffing needs. Post-registration critical care nursing courses were subsequently developed from the early 1960s in both Australasia and the UK.4,8 Courses ranged in length from 6 to 12 months and generally incorporated employment as well as specific days for lectures and class work. Given the local nature of these courses developed for the local needs of individual hospitals and regions, differences in content and practice therefore developed between hospitals, regions and countries.18–20

During the 1990s the majority of these hospital-based courses in Australasia were discontinued as universities developed postgraduate curricula to extend the knowledge and skills gained in pre-registration undergraduate courses. A significant proportion of critical care nurses now undertake specialty education in the tertiary sector, often in a collaborative relationship with one or more hospitals.4 One early study of students enrolled in university-based critical care courses in Australia21 identified a number of burdens (workload, financial, study–work conflicts), but also a number of benefits (e.g. better job prospects, job security).

Within Australia and New Zealand, most tertiary institutions currently offer postgraduate critical care nursing education at a Graduate Certificate or Graduate Diploma level as preparation for specialty practice, although this is often provided as a Master’s degree.22 In the UK, similar provisions for postgraduate critical care nursing education at multiple levels are available, although some universities also offer critical care specialisation at the undergraduate level (for example, King’s College, London). Education throughout Europe has undergone significant change in the past 10 years as the framework articulated under the Bologna Process has been implemented.23 In relation to critical care nursing, this has led to the expansion of programs, primarily at the postgraduate level, for specialist nursing education. Critical care nursing education in the USA maintains a slightly different focus, with most postgraduate studies being generic in nature, including a focus on advanced practice roles such as clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners, while specialty education for critical care nurses is undertaken as continuing education.24 Employment in critical care, with associated assessment of clinical competence, remains an essential component of many university-based critical care nursing courses.22,25

Both the impact of post-registration education on practice and the most appropriate level of education that is required to underpin specialty practice remain controversial, with no universal acceptance internationally.26–29 Globally, the Declaration of Madrid, which was endorsed by the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses, provides a baseline for critical care nursing education (see Appendix A for the position statement).5

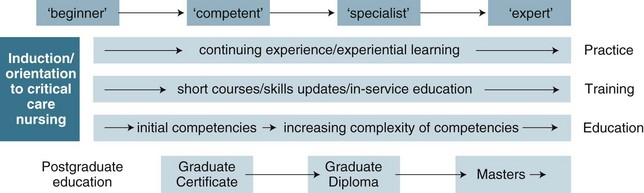

A range of factors continue to influence critical care nursing education provision, including government policies at national and state levels, funding mechanisms and resource implications for organisations and individual students, education provider and healthcare sector partnership arrangements, and tensions between workforce and professional development needs.13 Recruitment, orientation, training and education of critical care nurses can be viewed as a continuum of learning, experience and professional development.5 The relationships between the various components related to practice, training and education are illustrated in Figure 1.1, on a continuum from ‘beginner’ to ‘expert’ and incorporating increasing complexities of competency. All elements are equally important in promoting quality critical care nursing practice. Practice- or skills-based continuing education sessions support clinical practice at the unit level.30 (Orientation and continuing education issues are discussed further in the context of staffing levels and skills mix in Chapter 2.)

Many countries now incorporate requirements for continuing professional development into their annual licensing processes. Specific requirements include elements such as minimum hours of required professional development and/or ongoing demonstration of competence against predefined competency standards.31,32

Specialist Critical Care Competencies

Critical care nursing involves a range of skills, classified as psychomotor (or technical), cognitive or interpersonal. Performance of specific skills requires special training and practice to enable proficiency. Clinical competence is a combination of skills, behaviours and knowledge, demonstrated by performance within a practice situation33 and specific to the context in which it is demonstrated.34 A nurse who learns a skill and is assessed as performing that skill within the clinical environment is deemed competent. As noted above, a set of competency statements for specialist critical care practice comprises 20 competency standards grouped into six domains: professional practice, reflective practice, enabling, clinical problem solving, teamwork and leadership14 (see Appendix B). The validity of this structure of six domains has been questioned, however, as a number of competency statements are linked to several domains.35 Further research is therefore required to refine the structure of a competency model with improved construct validity.35 Other competency domains and assessment tools have also been developed.25 Although articulated slightly differently, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) provides ‘Standards of Practice and Performance for the Acute and Critical Care Clinical Nurse Specialist’,36 which outlines six standards of practice (assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation and evaluation) and eight standards of professional performance (quality of care, individual practice evaluation, education, collegiality, ethics, collaboration, research and resource utilisation) (see Online resources).

Critical Care Nursing Professional Organisations

Professional organisations representing critical care nurses were formed as early as the 1960s in the USA with the formation of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN).37 Other organisations have developed around the world, with critical care nursing bodies now operating in countries from Australasia, Asia, North America, South America, Africa and Europe. In 2001 the inaugural meeting of the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses (WFCCN) was formed to provide professional leadership at an international level.38,39 The ACCCN was a foundation member of the WFCCN and a member association of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine, and maintains a representative on the councils of both these international bodies. (See the ACCCN website, listed in Online resources, for further details about professional activities.)

Roles of Critical Care Nurses

As the discipline of critical care has developed, so too has the range of roles performed by specialty critical care nurses.40,41 The continuum of critical illness (see Chapter 4) includes pre-crisis/proactive care, management of the critical illness, and follow-up care in hospital, clinic and home settings.42 This continuum also includes the practice of palliative care in the ICU environment.43 Clinical (bedside) roles and nurse-to-patient ratios for various levels of critical care unit, as well as the roles of unit manager and clinical nurse educator, are discussed in Chapter 2. Practice issues for critical care clinicians are detailed in the remaining chapters of this book. Roles that apply to all nursing professionals are specifically highlighted; for example:

• carer, in Chapters 6, 7 and 8, all practice-related chapters in Section 2, and the specialty chapters in Section 3

• patient and family advocate, in Chapters 5 and 8

This section focuses on the scope of critical care nurses’ roles inside and external to the critical care area, and provides links to other specific chapters.44 These roles include:

• advanced practice48/nurse practitioner roles in ICU,46 trauma,49 emergency50 (Chapter 22), critical care outreach51/ICU liaison52–54 (Chapter 2)

Consultant

Expert clinicians in one of the subspecialties of critical care – emergency, general ICU, cardiology, cardiothoracic, neurosciences – play important roles in facilitating improvements in clinical practice for both critical care and non-critical care patients. The consultant’s role involves clinical practice, education, quality improvement and research activities.55 Within these work portfolios, leadership and the development and dissemination of knowledge45,46 within a multidisciplinary team are integral to effective practice.47 Practice includes role-modelling of expected behaviours, policy and clinical guideline development to support clinical care, and facilitating professional development of colleagues in collaboration with the nurse educator role. The benefits that this role brought to the critical care area led to the introduction of a similar service for non-critical care areas, particularly in the context of clinical deterioration of patients or for patients recently discharged from the ICU, with the development of critical care outreach or ICU liaison nurse roles (see Chapter 2 for further discussion of these services).

Advanced Practice Nurse/Nurse Practitioner

Processes for authorisation to practise as a nurse practitioner (NP) have been introduced by professional registration agencies in Australia and New Zealand, with similar roles present in the UK and USA prior to this.48 Nurse practitioner roles in ‘critical care’ (or high dependency) range from emergency department practitioners through to community-based cardiac failure specialists, and, as noted above for the nurse consultant’s role, often lack clarity regarding their scope of practice.56,57 Factors influencing the establishment of these roles include the accrediting process, defining the scope of practice through specific clinical practice guideline development, prescribing rights and the prevailing medical views, and the level of support provided by health service administrators for the implementation, development and evaluation of the role.48,56 Advanced practice roles in the emergency department are the most well-established in the critical care domain (see Chapter 22).

Clinical Decision Making

the cognitive processes and strategies that nurses use to understand the significance of patient data, to identify and diagnose actual or potential patient problems, and to make clinical decisions to assist in problem resolution and to achieve positive patient outcomes.58

Theoretical Perspectives on Decision Making

The analytical approaches arise from a positivist or rationalist perspective and focus on analysing behaviours and the steps involved in problem solving. Some of the specific theories that fall into this category include information-processing theory (IPT)59 and decision analysis theory (DAT).60

Fundamental to IPT is the premise that reasoning consists of a relationship between the problem solver and the context within which the problem occurs. This theory asserts that relevant information is stored in one’s memory and that problem solving occurs when the problem solver retrieves information from both short- and long-term memory. Additionally, IPT claims that there are limits to the amount of information that can be processed at any given time. Thus, IPT focuses on understanding how information is gathered, stored and retrieved. DAT focuses on the use of decision trees, mathematical formulas and other techniques to determine the likelihood of meaningful clinical data. These rationalist approaches focus on diagnosing a problem, intervening and evaluating the outcome.61

Contrary to the analytical approaches, intuitive approaches (also termed humanistic, hermeneutic or phenomenological) focus on the importance of intuitive knowledge and context in clinical decision making.40,62,63 That is, expert intuition develops with experience and can be used to make complex decisions. Both intuitive knowledge and analytical reasoning contribute to clinical decisions.63 Intuitive approaches to decision making therefore focus on understanding the development of intuition, the role of experience and articulating how nurses use intuition to make a decision. In addition, Australian authors64 have described a naturalistic framework to examine critical care nurses’ decision making, describing it as a way of considering how people use their experience when making real-life decisions.

Research on Decision Making in Critical Care Nursing

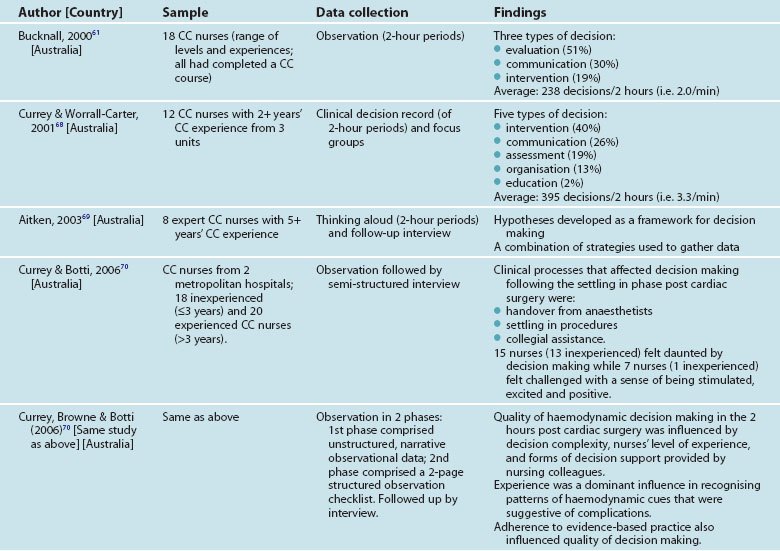

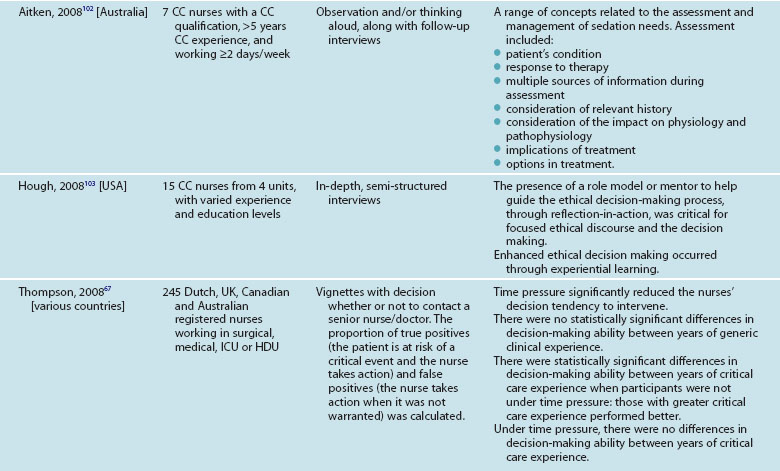

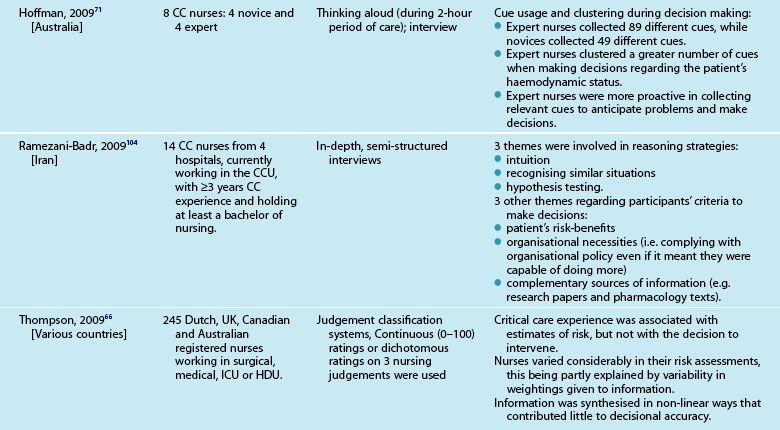

Critical care nursing practice has been the focus of many studies on decision making. As multiple, complex decisions are made in rapid succession in critical care, it is an ideal setting for studying clinical decision making.61 The seminal work by Benner and colleagues40,63,65 focused on critical care nurses. Table 1.1 summarises 10 studies (11 publications) conducted on critical care nurses’ decision making over the past decade.

Of note, 7 of the 10 studies were conducted in Australia, with two multinational studies also including Australia. All but two studies66,67 used qualitative approaches such as observation, interviewing and thinking aloud. Two studies reported the types and frequency of decisions made during the time period and identified that critical care nurses’ decisions were related to interventions and communication,61,68 evaluation,61 assessment, organisation and education.68 A further study demonstrated that critical care nurses generate one or more hypotheses about a situation prior to decision making.69 All three studies highlighted the importance of enabling expert nurses to provide a narrative account of their practice. Other studies indicated that experienced and inexperienced nurses differ in their decision making skills,67,70,71 and that role models or mentors are important in assisting to develop decision making skills.72

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree