Chapter 4. Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Because of their major thought disorder, individuals with schizophrenia are unable to process incoming information accurately, and as a result have difficulty responding appropriately to the outside world. As a result, the person’s unusual verbal responses and behaviors are incongruent with the situation, or sometimes may become bizarre (person actively and openly talks to self, or to other people and things that do not exist; wears strange clothing, e.g., an overcoat in the summer; avoids personal hygiene; avoids contact with others). Other people have difficulty understanding the meaning of both verbal and nonverbal communication of the disordered person, resulting in discomfort or frustration, and ultimately rejection of the individual by society. Alienation by friends, family, or the community only compounds symptoms of schizophrenia.

The media frequently generalizes and sensationalizes schizophrenia by focusing on one aspect of the complex disorder, which is the risk for violence. In actuality, a very small percentage of people with the disorder are aggressive or dangerous, and most individuals with schizophrenia instead become withdrawn and fearful. The media often promotes unwarranted fear in the public and avoidance responses toward these individuals, creating even more loneliness in their lives. Stigma in relation to mental disorders is one of the major problems perpetuated in this country. It interferes with open acceptance and appropriate, adequate treatment of the illnesses.

Treatment has progressed remarkably in the last few decades and allowed many clients with schizophrenia to rejoin society, giving them hope and a will to continue living and functioning in meaningful ways when not struggling with acute episodes. The use of antipsychotic medications to alleviate symptoms has proven effective for many clients. However, complete recovery from schizophrenia is the exception rather than the rule. Regardless of the type, symptoms of schizophrenia are not curable as in, for example, the common cold. Instead, symptoms of the disorder typically persist or recur many times over a client’s lifetime. Schizophrenia interferes with personal, social, and occupational functions of the client and significant others during these episodes.

Schizophrenia usually makes an untimely debut. The first episode most often occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood. As a result, it dramatically affects important milestones of this period, including education, employment, and relationships. Like a tumbling house of cards, all aspects of the person’s well-being are often disrupted and disconnected at a time when the maturing individual would otherwise be involved in one of the most productive times of his or her life.

▪ “He/she became an entirely different person.”

▪ “Our life together as we knew it ended, and chaos took its place.”

▪ “It pulled the plug out of life as we knew it.”

▪ “A dark cloud descends over our lives when episodes occur.”

These statements help nurses to begin understanding the impact of schizophrenia on individuals and families.

ETIOLOGY

The definitive etiology of schizophrenia is yet to be determined. Current research, however, favors the diathesis-stress model, which states that the disorder is caused by constitutional/genetic predisposition or vulnerability, coupled with biologic, environmental, and psychosocial stressors. Despite evidence for genetic etiology, specific genes responsible for schizophrenia have not yet been identified; multiple genes are thought to be involved. Several inherent anatomic physiologic abnormalities and changes have been discovered in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia. Likewise, many external factors that may influence onset have also been identified.

Schizophrenia is most likely caused by a convergence and interaction of genetic and environmental factors (Box 4-1). Questions remain about whether the brain changes are the cause versus the consequence of the disorder, or in some cases the result of treatment with medications.

BOX 4-1

Genetic factors (see Figure 4-1)

Neurodevelopmental factors: brain abnormalities

▪ Enlarged ventricles

▪ Cortex laterality (left localized)

▪ Temporal lobe dysfunction

▪ Phospholipid metabolism

▪ Frontal lobe dysfunction

▪ Brain circuitry dysfunction

▪ Neuronal density

Neurotransmitter systems dysfunction

▪ Dopaminergic dysregulation (excess)

▪ Serotonin (2A receptor gene variant)

Prenatal stressors

▪ Depression

▪ Influenza

▪ Poverty

▪ Rh-factor incompatibility

▪ Physical injury

Development/birth-related findings

▪ Short gestation

▪ Low birth weight

▪ Delivery complications

▪ Disrupted fetal development

▪ Inadequate mother-infant bonding

Environmental pollutants

Multiple/varied psychosocial stressors

Viral infections of central nervous system

* Etiology is attributed to a combination of biologic, psychologic, psychosocial, and environmental factors.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Schizophrenia is present in approximately 1% of the world’s population. In the United States and United Kingdom, some Asian American and African American groups are diagnosed more often as having schizophrenia than other races. It is uncertain whether this results from actual racial differences, clinical interviewer bias, or insensitivity to cultural differences. Cultural variations may be part of the explanation because normal behavior in one culture may be considered a disorder in another culture. For example, seeing or hearing the voice of a dead loved one is not considered abnormal in some areas of the world but would probably be considered psychotic symptoms in the general population of the United States. When a clinician interviews clients from a different culture and lacks comprehensive understanding of that culture’s differences, the clinician may have difficulty avoiding influences from personal, cultural, and social standards. Such influences may affect assessment outcomes.

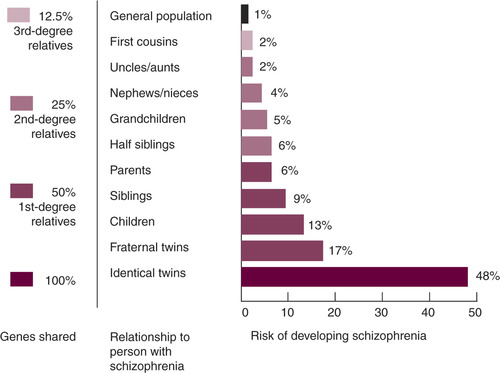

Biologic first-born relatives of individuals with schizophrenia have a 10 times greater risk than the general population for developing the disorder. Studies of twins, adoptees, and families strongly support this finding (Figure 4-1). Some relatives of people with schizophrenia are also at risk for related mental disorders, including schizoaffective disorder and schizotypal, paranoid, schizoid, and avoidant personality disorders.

|

| Figure 4-1 (From Surgeon General Report, 1999.) |

Onset of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia usually occurs in late adolescence to the mid-30s. Two patterns, one acute and the other chronic, mark the onset of this disorder. In one pattern of onset, the first psychotic episode may occur abruptly in a person previously considered normal by most standards. This acute onset is often associated with recent major psychosocial stressors (death of a loved one, leaving home for college or the military, breakup of relationship). A prodromal period usually precedes the disorder, in which the person begins to behave in unusual ways that contrast with the individual’s typical behavior. This behavior worries family members, who frequently say the person has “changed.” Symptoms show a decline in normal function. Behaviors unusual for the person include the following:

▪ Increasing isolation

▪ Withdrawal from usual contacts

▪ Loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities

▪ Neglected hygiene/grooming

▪ Expression of unusual beliefs/experiences

▪ Unprovoked anger

Some or all of these symptoms may precede a psychotic episode.

A second pattern of onset consists of a lifelong history of marginal functioning and unusual behaviors and perceptions, as reported by the client, family, and teachers. This history includes the following:

▪ Ongoing problems with family relationships

▪ Few if any friends (“loner”)/few social contacts

▪ School truancy/low grades

▪ Trouble with the law

▪ Lack of interest in school or work

▪ Neglected hygiene/dress/grooming

▪ Excessive interest/participation in unusual topics/activities (cults, outlying spiritual attractions, the paranormal, vampires), either in person or through virtual participation in video games/computer access

Within this time the eruption of one or more psychotic episodes occurs. This long-standing second pattern for schizophrenia may be associated more with signifi-cant neurodevelopmental/neurophysiologic deficits or changes.

Schizophrenia affects both genders equally, but usually at different times of life for men and women. Age of onset in most cases is earlier for men (18 to 25 years) than women (25 to 35 years). Childhood schizophrenia is rare. Also once thought to be rare, late-onset cases (older than 50 years) occur more often in women than men. One theory holds that women are protected by female hormones, which diminish with menopause, leaving them more vulnerable to the disorder. Additional psychosocial stressors in this age group may trigger the disorder.

Course of Schizophrenia

The course of schizophrenia varies. Some clients experience periods of exacerbations and remissions, whereas others have severe and persistent symptoms. In some cases the positive symptoms abate, but the negative symptoms often persist. Clients seldom return to their normal, premorbid level of functioning. The course for schizophrenia is influenced by many factors (Box 4-2).

BOX 4-2

Severity of symptoms

Access to treatment

Client response to therapies

Client awareness of condition/situation

Motivation and ability to improve

Accepting support network

▪ Family

▪ Treatment sites/staff

▪ Economic aspects

▪ Appropriate social diversions

▪ Skills retraining/rehabilitation facilities

Drug Use

Comorbidity rates of schizophrenia with substance-related disorders are high. Nicotine dependence is a particular problem, with 80% to 90% of clients with schizophrenia being dependent smokers who also choose high-nicotine brands. Several other drugs, often illegal ones, are frequently used by individuals with this diagnosis. The dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and a drug abuse or drug-dependent diagnosis is now common.

Clients with schizophrenia, who have compromised insight and judgment from the disorder, often are victims of ruthless drug peddlers who use the clients to meet their own needs. For example, clients may spend their meager income on drugs instead of psychotropic medications, rent, or food, or they may become involved in selling sexual favors in exchange for drugs. Clients may be abused emotionally, psychologically, socially, morally, and often physically. In some individuals, the first psychotic episode is triggered by drug experimentation or use; however, the reader is cautioned not to confuse every drug induced psychosis, with the disorder of schizophrenia. Specific criteria constitute the diagnosis of schizophrenia and are discussed in “Types of Schizophrenia” in this chapter (see p. 145).

Mortality and Suicide

The mortality rate in schizophrenia is high. Many of these clients are at higher risk for some diseases and conditions because of their disorder, which leaves them uninformed and unprotected.

The suicide rate among clients with schizophrenia is also high. They may commit suicide during episodes of active psychosis, when delusions or hallucinations prevail, or during lucid periods when they are able to more clearly examine their quality of life then choose not to continue the struggle.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

One criterion included in all types of schizophrenia is psychosis, which is the defining characteristic of this disorder and must be present to make the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Other categories of mental disorders (major depression with psychotic features, Alzheimer’s disease with psychotic features) may include psychotic symptoms as a component, but these are not considered psychotic disorders.

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The term psychosis has been defined and described in many ways over the decades. Multiple definitions have found favor at different times in the history of the reporting and recording of psychiatric disorders. No single definition of psychosis receives total acceptance (see Glossary).

One effective way to understand the psychosis of schizophrenia is to refer to the description of positive and negative symptoms. Both types of symptoms refer to function, as follows:

▪ Positive symptoms represent a distortion or excess of normal function and include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking/speech, and grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior.

▪ Negative symptoms represent a decrease, loss, or absence of normal function and include flat affect, alogia, and avolition (Box 4-3).

BOX 4-3

American Psychiatric Association

American Psychiatric Association

POSITIVE SYMPTOMS

▪ Delusions are firmly held erroneous beliefs caused by distortions/exaggerations of reasoning and misinterpretations of perceptions/experiences. Delusions of being followed or watched are common, as are beliefs that comments, radio/TV programs, and other sources are sending special messages directly to the client.

▪ Hallucinations are distortions/exaggerations of perception in any of the senses, although auditory hallucinations (“hearing voices” within, distinct from one’s own thoughts) are the most common, followed by visual hallucinations.

▪ Disorganized speech/thinking, also described as thought disorder or loosening of associations, is a key aspect of schizophrenia. Disorganized thinking is usually assessed primarily based on the client’s speech. Therefore tangential, loosely associated, or incoherent speech severe enough to substantially impair effective communication is used as an indicator of thought disorder by the DSM-IV-TR.

▪ Grossly disorganized behavior includes difficulty in goal-directed behavior (leading to difficulties in activities of daily living), unpredictable agitation or silliness, social disinhibition, or behaviors that are bizarre to onlookers. Their purposelessness distinguishes them from unusual behavior prompted by delusional beliefs.

▪ Catatonic behaviors are characterized by a marked decrease in reaction to the immediate surrounding environment, sometimes taking the form of motionless and apparent unawareness, rigid or bizarre postures, or aimless excess motor activity.

▪ Other symptoms in schizophrenia are not common enough to be definitional alone:

▪ Affect inappropriate to the situation or stimuli

▪ Unusual motor behavior (pacing, rocking)

▪ Depersonalization

▪ Derealization/somatic preoccupations

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS

▪ Affective flattening is the reduction in the range and intensity of emotional expression, including facial expression, voice tone, eye contact, and body language.

▪ Alogia, or poverty of speech, is the lessening of speech fluency and productivity, thought to reflect slowing or blocked thoughts, and often manifested as laconic, empty replies to questions.

▪ Avolition is the reduction, difficulty, or inability to initiate and persist in goal-directed behavior; it is often mistaken for apparent disinterest.

Data from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

In addition to the positive and negative symptoms, other symptoms are evident in schizophrenia. Note that each type of the disorder includes specific criteria and that all symptoms will not be demonstrated in every type of schizophrenia.

Duration of Symptoms

Another criterion that defines schizophrenia is duration of symptoms. Before the diagnosis of schizophrenia is made, at least 6 months of persistent disturbance exists, with 1 month of active-phase symptoms (see Box 4-3). When treated with medications and relevant psychosocial therapy, clients with schizophrenia have a variable active phase.

Acute Phase of Schizophrenia

Symptoms of the active, or acute, phase of schizophrenia vary. Disturbances occur in multiple psychologic and psychosocial areas, including perception, thought, mood, and behavior.

Thought Disturbance

Thought disturbance may be manifested in many ways. Disturbed content refers to dysfunctional beliefs, ideas, and interpretations of actual internal and external stimuli. Delusions are examples of disturbed thought content; some common types of delusions in schizophrenia are persecutory, grandiose, religious, and somatic, as follows:

▪ The client believes that stereo speakers, TV, or computers are controlling her thoughts.

▪ Intergalactic electrical waves are beaming on the world, ready to destroy the client.

▪ The client has the power to change the seasons.

▪ The client believes he is the messenger from God.

▪ The client has a demon in the stomach that causes sounds.

Other symptoms include thought broadcasting (thoughts or ideas are being transmitted to others), thought insertion (others can put thoughts into the client’s mind), and thought withdrawal (thoughts can be taken from the client’s mind).

Content disturbance is also noted by ideas of reference, which are beliefs that other people or messages from the media (TV, radio, newspaper) are directly referring to the client as follows:

▪ Two strangers may be across the room holding a conversation about the weather, and the client believes they are talking about her.

▪ The president of the United States gives a speech on TV about the space program, and the individual believes it is a message for him to become an astronaut.

The client’s preoccupation with particular thoughts or ideas that are persistent and cannot be eliminated (obsessional thinking) also represents content disturbance. Frequently, such thoughts are accompanied by ritualistic behavior. Clients with schizophrenia often make symbolic references to actual persons, objects, or events. For example, the color red may symbolize anger, death, or blood to the client.

Incoherence, loose associations, tangentiality, circum-stantiality, neologisms, “word salad,” echolalia, perseveration, verbigeration, and autistic and dereistic thinking may be noted by staff as the client speaks, writes, or draws.

Disturbed thought process includes thought blocking, poor memory, symbolic or idiosyncratic association, illogical flow of ideas, vagueness, poverty of speech, and impaired ability to abstract ( concrete thinking)/reason/calculate/use judgment.

Affective Disturbance

Affective disturbance may be characteristically evidenced by flat (blunted) or inappropriate affect. The person with flat affect demonstrates little or no emotional responsivity. Facial expression is immobile, voice is monotonous, and the client describes not being able to feel as intensely as he or she once did or not being able to feel at all. Inappropriate affect is manifested by emotional expression that is incongruent with verbalizations, situation, or event; client’s ideation and description do not match the affective display. For example, the individual may describe the death of a parent and laugh. Other affective manifestations may appear as sudden, unprovoked demonstrations of angry or overly anxious behavior, silliness, or giddiness. The person may be responding to internal stimuli at such times (hallucinations).

Persons with schizophrenia may demonstrate or express a wide range of emotions and say they feel terrified, perplexed, ambivalent, ecstatic, omnipotent, or overwhelmingly alone, or that they do not feel anything at all. These clients are frequently not in touch with their feelings or have difficulty expressing them.

N ote: Staff’s knowledge of the action and adverse effects of antipsychotic medications is essential because affective displays may represent the manifestations of schizophrenia or may be a reaction to the medications. Interventions depend on the nurse’s correct assessment to avoid overmedication or undermedication of the client.

Perceptual Disturbance

Perceptual disturbances may include hallucinations, illusions, and boundary and identity problems.

Hallucinations.

A common perceptual dysfunction in schizophrenia is the hallucination, a sensory perception by an individual that is not associated with actual external stimuli. Although hallucinations may occur in any of the senses (hearing, sight, taste, touch, smell), the most common are auditory hallucinations. The voices that clients hear carry messages of various types but are usually derogatory, accusatory, obscene, or threatening.

It is important for staff to thoroughly assess the auditory command type of hallucination, in which voices tell the client to harm self or others, so that staff can initiate protective interventions. Some clients describe their auditory hallucinations as thoughts or sounds rather than voices.

Visual, gustatory, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations are less common in schizophrenia. Delusions may or may not accompany hallucinations. Delusional content usually parallels or incorporates the hallucination, as if the client is attempting to “make sense” of the hallucination.

Illusions.

Occasionally the client may experience illusions, which are misinterpretations of actual external environmental or sensory stimuli. For example, as the sun is setting, the patient looks out a window and tells staff that he sees his grandfather, but the object is actually a bush. Differentiation between illusions and hallucinations by staff is often difficult and requires keen assessment and patience.

Boundary and Identity Problems.

The client with schizophrenia may seem confused and lack a clear sense of self-awareness. The client is not sure of personal boundaries and sometimes cannot differentiate self from others or from inanimate objects in the environment. This is often frightening for the client. The client may also describe depersonalization or derealization phenomena. In depersonalization, individuals have the sense that their own bodies are unreal, as if they are estranged and unattached to the world or the situation at hand. Derealization is the experience that external environmental objects are strange or unreal.

A client with schizophrenia may perceive a loss of sexual identity and doubt his or her own gender or sexual orientation. This may be frightening for the client and should not be interpreted as homosexuality by the staff.

Behavioral Disturbance

Behavioral disturbances may be demonstrated by impaired interpersonal relationships. Because of the difficulties these clients have with communication and interaction, the individual is frequently emotionally detached, socially inept, and withdrawn and has difficulty relating to others. Forming a therapeutic relationship with these clients is a challenge because of the detached affective responses, illogical thinking, egocentrism, lack of trust, and other problems described previously. A concerted effort must be made to engage the client with schizophrenia because the usual encouraging cues to continue interaction are often absent. The nurse is aware that during acute episodes the client may be more isolative and restricted in thought and speech production (alogia), so initiation of contacts by the nurse is imperative.

Psychomotor disturbances such as grimacing, bizarre posturing, unpredictable and unprovoked wild activity, odd mannerisms, and compulsive stereotypical or ritualistic behavior may be present, or the patient may stare into space, seem totally out of touch with the external surroundings or persons in it, and show little or no emotional response, spontaneous speech, or move-ment. Clients may appear stiff or clumsy, be socially unaware of their appearance and habits, and fail to bathe or wash their clothes. They may spit on the floor and in extreme cases may regressively play with or smear feces. Clients frequently demonstrate anxious, agitated, fearful, or aggressive behavior.

American Psychiatric Association

Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Schizophrenia subtypes

▪ Paranoid

▪ Disorganized

▪ Catatonic

▪ Undifferentiated

▪ Residual

Schizophreniform disorder

Schizoaffective disorder

Delusional disorder

Brief psychotic disorder

Shared psychotic disorder

Schizophrenia from other causes

▪ Medical conditions

▪ Medications/drugs/other substances

Another characteristic manifested in schizophrenia is ambivalence, or opposing thoughts, ideas, feelings, drives, or impulses occurring in the same person at the same time. For example, when asked to come to the group meeting, the client may step out of and reenter his or her room dozens of times, unable to make a decision. Negativistic behavior is usually demonstrated as frequent oppositions and resistance to suggestions.

DSM-IV-TR Criteria

A diagnosis of schizophrenia depends on the symptoms demonstrated by the client and is assigned for the purposes of treatment focus. Various types of schizophrenia have been identified according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (see the DSM-IV-TR box; see also Appendix L).

TYPES OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Paranoid Type

Distinguishing characteristics of paranoid schizophrenia are (1) persistent delusions with a single or closely associated, tightly organized theme, usually of persecution or grandeur and (2) auditory hallucinations about single or closely associated themes. Clients are guarded, suspicious, hostile, angry, and possibly violent. Anxiety is pervasive in the paranoid disorder. Social interactions are intense, reserved, and controlled. Onset is later in life than with other types. Paranoid schizophrenia has a more favorable prognosis as a rule, particularly in regard to independent living and occupational function.

Disorganized Type

The distinguishing characteristics of disorganized schizophrenia are grossly inappropriate or flat affect, incoherence, and grossly disorganized primitive and uninhibited behavior. These clients appear very odd or silly. They have unusual mannerisms, may giggle or cry out, distort facial expressions, complain of multiple physical problems (hypochondriasis), and are extremely withdrawn and socially inept. Invariably the onset is early, and the prepsychotic period is marked by impaired adjustment, which continues after the acute episode. Clients may hallucinate and have delusions, but the themes are fragmented and loosely organized. Other classifications name this type hebephrenic.

Catatonic Type

The distinguishing characteristic of catatonic schizophrenia is marked disturbance of psychomotor activity. The behavior of the catatonic client is manifested as either motor immobility or psychomotor excitation, or the client can alternate between the two states.

The client may be immobile (stuporous) or exhibit excited, purposeless activity. The client may be out of touch with the environment and display negativism, mutism, and posturing. These individuals can be placed in bizarre positions (waxy flexibility), which they may rigidly maintain until moved by a staff member. It is as if they do not even feel their bodies. Careful supervision is required to prevent injury, promote nutrition, and support physiologic/psychologic functions.

Undifferentiated Type

Clients with a diagnosis of undifferentiated schizophrenia display florid psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, incoherence, disorganized behavior) that do not clearly fit under any other category.

Residual Type

The residual category is used when a client has experienced at least one acute episode of schizophrenia and is free of psychotic symptoms at present but continues to exhibit persistent signs of social withdrawal, emotional blunting, illogical thinking, or eccentric behavior.

Associated Types

Schizophreniform Disorder

Diagnostic criteria for schizophreniform disorder meet those for schizophrenia except for two factors: (1) duration of the illness is at least 1 month but less than 6 months, and (2) social/occupational function may not be impaired.

Schizoaffective Disorder

Defining characteristics of schizoaffective disorder are demonstration of symptoms of both schizophrenia (delusions and/or hallucinations, disorganized speech/behavior, negative symptoms) and a mood disorder (major depressive, manic, mixed). The episode must last for 1 month.

OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS

Delusional Disorder

The presence of one or more nonbizarre delusions that persist for 1 month or more defines delusional disorder. Bizarre delusions are composed of strange and markedly unusual or incredible content. For example, a person believes his brain was removed by alien beings and replaced by a computer that controls his life. Nonbizarre delusions, however, are plausible and could possibly exist in the individual’s life. For example, a student believes there is a conspiracy to keep her from graduating from college. Subtypes of delusional disorder are identified by their delusional themes, as follows:

▪ Erotomanic. The theme centers around belief and conviction that another person is in love with the client, which in fact is untrue. The individual may go to great lengths to communicate with the loved object (stalking, phoning, spying).

▪ Jealous. The theme is that the individual’s lover or spouse is unfaithful without real evidence to support the belief. Incorrect inferences are made about the spouse’s clothes or bed sheets, and efforts are made to follow or “catch” the partner in “the act.”

▪ Grandiose. The theme focuses on the individual as having extraordinary or important talent or special knowledge; intimately knowing a famous person or group; or less frequently, that the individual is a famous person.

▪ Persecutory. The theme centers on the belief that the individual is a victim of conspiracy, poisoning, spying, harassment, or cheating. The person frequently is angry or resentful or may be violent.

▪ Somatic. The belief focuses on bodily sensations or functions. Most frequent somatic delusions include belief that the person has a foul odor emanating from a body part (mouth, vagina, skin), that insects or parasites are on or in the body, or that a body part (bowel) is nonfunctional.

Brief Psychotic Disorder

The defining characteristic of brief psychotic disorder is at least one of the following symptoms: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, or behavior disturbance (disorganized or catatonic). Symptoms last at least 1 day but less than 1 month. The person returns to premorbid level of function following the episode.

Shared Psychotic Disorder

Shared psychotic disorder, a delusional disorder also known as folie à deux, develops in a person who is involved in a relationship with another individual who already has a psychotic disorder with prominent delusions.

Psychotic Disorder due to Medical Condition

Defining characteristics are prominent hallucinations and/or delusions because of physiologic effects of a medical condition.

Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder

Defining characteristics are prominent hallucinations or delusions because of physiologic effects of a substance (drugs of abuse, medication, or toxin). The disorder first occurs during intoxication or withdrawal stages but can last for weeks thereafter.

INTERVENTIONS

There are three distinct treatment phases for schizophrenia: (1) active phase, (2) maintenance phase, and (3) rehabilitation phase. Treatment is aimed at alleviation of symptoms, improvement in quality of life, and restoration of productivity within the client’s capacity. In each treatment stage, evidence indicates that a combination of modalities, including psychopharmacology, psychosocial therapy, and psychoeducation of client and family, is most effective.

Frequently, intensive forms of therapy and case management involving interdisciplinary teams are necessary for clients whose symptoms severely disrupt their lives and the lives of family members, especially when symptoms are persistent. Clients and significant others are encouraged to learn to recognize symptom changes and report them to designated members of the treatment team to prevent more serious episodes whenever possible.

The following modalities are recognized forms of intervention for clients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia. Additionally, the care plans provide specific nursing interventions and rationale for therapeutic interactions with these clients.

Medications

Although schizophrenia often is not curable, it is treatable, and current methods of treatment are effective. Schizophrenia became more manageable with the advent of antipsychotic medications, also referred to as neuroleptics. The first-generation, conventional antipsychotics relieved the positive symptoms, which was a milestone but did little to target the negative symptoms (see Box 4-3). Even though the clients’ delusions, hallucinations, and incoherence that define psychosis subsided, their lack of motivation and decreased desire to engage in activities persisted, leaving them uninvolved, seclusive, and isolated. Newer generation neuroleptics act on the positive symptoms and are often effective in alleviating negative symptoms as well. Also, fewer adverse side effects are seen with the newer generation antipsychotics. Nurses continually observe for two adverse effects that may result from use of antipsychotic medications. These are extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) (BOX 4-4 and BOX 4-5). Appendix H describes antipsychotic medications. Additional psychotropic medications may be prescribed in conjunction with antipsychotics (i.e., antianxiety or mood stabilizers).

BOX 4-4

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are a variety of motor-related side effects that result from the dopamine-blocking effects of antipsychotic medications (most commonly the typical group).

DYSTONIA

Occurs in 10% of clients treated. Spasms affecting various muscle groups may be frightening and result in difficulty swallowing, jeopardizing the person’s airway.

Treatment

▪ Mild cases: oral anticholinergic drugs

▪ Severe or unresolved cases: benztropine (Cogentin) 2 mg IM and diphenhydramine (Benadryl) 50 mg IM

PSEUDOPARKINSONISM

Occurs in 15% of clients treated. A variety of symptoms including tremors, slowed or absent movement, muscle jerks (cogwheel rigidity), shuffling gait, loss of facial muscle movement (masked facies), and drooling.

Treatment

Anticholinergic drugs or dopamine agonists

AKATHISIA

Literally means “not sitting.” Occurs in 25% of clients treated. Motor restlessness, pacing, rocking, foot-tapping, inability to lie down, or sit still. Can be confused with anxiety, so keen assessment is critical.

Treatment

▪ Reduction in antipsychotics (may not be practical if psychosis is responding well to antipsychotics).

▪ Beta-blockers and benzodiazepines are the most common adjunctive treatment.

▪ Occasionally benztropine if client is able to tolerate.

TARDIVE DYSKINESIA

Literally means late-occurring abnormal movements. Occurs in 4% of clients treated; may be irreversible in 50% of those clients. Classically described as oral, buccal, lingual, and masticatory, these rapid, jerky movements can occur anywhere in the body.

Treatment

▪ Prevention by monitoring the client frequently during treatment.

▪ Withdrawing antipsychotics over time may cause temporary increase in symptoms.

▪ Benzodiazepines can be used, although relief generally lasts only several months.

▪ Vitamin E has been used with inconsistent and modest results.

BOX 4-5

A potentially fatal but rare consequence of drug therapy, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) has a mortality rate of approximately 10%.

RISK FACTORS

▪ High-potency, conventional antipsychotics

▪ High doses of antipsychotics

▪ Rapid increase in dosage

SYMPTOMS

▪ Decreased level of consciousness

▪ Greatly increased muscle tone (rigidity)

▪ Autonomic dysfunction (hyperthermia, labile hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, drooling)

NMS is believed to result from dopamine blockade in the hypothalamus. Muscle necrosis can be so severe that it causes myoglobinuric renal failure. Laboratory abnormalities include greatly elevated creatine phosphokinase levels and leukocytosis.

TREATMENT

▪ Discontinue antipsychotic medications.

▪ Keep patient well hydrated.

▪ Administer antipyretics and provide cooling blankets if hyperthermia exists.

▪ Treat arrhythmias.

▪ Administer low doses of heparin to decrease the risk of pulmonary emboli.

▪ Administer bromocriptine mesylate (dopamine agonist) and dantrolene (direct-acting skeletal muscle relaxant) to reduce muscle spasm.

N ote: Other medications may be added to the antipsychotic regimen. Often clients will be prescribed antianxiety medications and mood stabilizers. Choice of medications depends on symptoms.

Therapies

Therapeutic Nurse-Client Relationship

People with schizophrenia have difficulty communicating and being accepted. The nurse-client relationship is a therapeutic vehicle for the person with schizophrenia to find acceptance and gain self-esteem. Within the trusting relationship the client can learn and practice new skills, receive nonjudgmental feedback about progress, and gain support and encouragement in the process. Focus is on interpersonal communication, socialization skills, independence, and skills for activities of daily living.

Group Therapy

Group therapies that focus on assisting clients and families in practical life skills are much more effective than psychodynamic types of therapy aimed at gaining insight. Because clients with schizophrenia have cognitive dysfunction such as loose associations and disorganized thinking, the insight-oriented therapies often prove to be nontherapeutic for clients who are unable to participate.

Individuals who may be psychotic are more successful in a low-stress group whose members receive positive reinforcement for even minimal functioning. The goals of these focus groups are realistic, meet the needs of the members, and address such issues as identification and support of strengths, hygiene/grooming, activities of daily living, socialization skills, motivation, self-esteem problems, and stress and anxiety reduction. Anxiety-reducing strategies include deep-breathing and relaxation exercises (see Appendix G).

Psychosocial Therapy

Psychosocial therapy is a necessary component in comprehensive care of clients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology coupled with support therapies has proven more effective than either form of therapy alone. During all stages of schizophrenia the medications either relieve symptoms or help to prevent symptoms from returning, thereby enabling the client to be more receptive to other types of psychosocial therapy. Because a major characteristic of schizophrenia is the impaired ability to form and maintain interpersonal relationships, a major focus of interventions centers on helping the client enter into and maintain meaningful socialization consistent with the client’s ability.

Family Therapy

Because the value of family support for the person with schizophrenia is immeasurable, family therapy is imperative whenever available. In therapy the families learn about schizophrenia and how to (1) prevent or reduce relapses, (2) give and gain support from others, (3) receive direction and resource aids in crises, (4) avoid crises, and (5) learn skills for problem solving, communicating, daily living competencies, and behavior modification.

Long-term studies have consistently found that family intervention improves client and family function, increases feelings of well-being, and prevents or delays symptom relapse. In most areas of the United States, groups of families of the clients with severe mental impairment such as schizophrenia, meet and learn from each other, provide support for each other, and show strength in numbers when addressing governing bodies to improve legislation for the mentally disordered population.

Community-Based Treatment

Severe and persistent mental disorders such as schizophrenia require intervention on several levels. Inpatient services focus on symptom amelioration, reduction of risk for danger to self and others, reintegration, and discharge planning for the client’s return to the community. Because of the type and severity of symptoms, clients with schizophrenia frequently are unable to function independently day to day when discharged from the inpatient setting back into the community. These clients are often placed in ongoing outpatient day treatment programs, where they benefit from daily contact with skilled staff and other clients. Staff assesses and monitors the client’s mental status and medications and provides opportunities for socialization with staff and others. Clients are encouraged to participate in scheduled meetings, groups, and activities consistent with their ability. An interdisciplinary treatment team is usually involved in the client’s care and is composed of nurses, physicians, social workers, and other therapists as budget and policy allow.

Support and education groups for clients and families are usually available in the community after clients are discharged. A comprehensive treatment focus usually includes rehabilitation and inclusion in vocational training or jobs if the client is able. A large percentage of the homeless population has mental disorders, and often their needs are minimally met or unmet. This is a harsh reality that remains open for improvement by U.S. cities, the states, and the federal government. Pastoral counseling is provided when this is the client’s preference (see Appendixes F and G).

PROGNOSIS AND DISCHARGE CRITERIA

Complete remission is uncommon in clients with schizophrenia, but several factors have been associated with a better prognosis (Box 4-6). Some types of schizophrenia also have a better prognosis (paranoid type) than others (undifferentiated type).

BOX 4-6

Schizophrenia

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

FAVORABLE COURSE/PROGNOSIS

▪ Good premorbid social, sexual, and work/school history

▪ Preceded by definable major psychosocial stressors or event

▪ Late onset

▪ Acute onset

▪ Treatment soon after episode onset

▪ Brief duration of active phases

▪ Adequate support systems

▪ Paranoid/catatonic features

▪ Family history of mood disorders

UNFAVORABLE COURSE/PROGNOSIS

▪ Poor premorbid history of socialization

▪ Early onset

▪ Insidious onset

▪ No clear precipitating factors

▪ Withdrawn/isolative behaviors

▪ Undifferentiated/disorganized features

▪ Few if any support systems

▪ Chronic course with many relapses and few remissions

Discharge criteria are tailored to meet each client’s needs and problem areas, with a focus on reintegration into the family and the community. The following basic list of criteria may be modified and expanded to fit the client’s discharge plan:

Client:

▪ Verbalizes absence or reduction of hallucinations and delusions.

▪ Identifies psychosocial stressors/situations/events that trigger hallucinations and increased delusions.

▪ Recognizes/discusses connections between increased anxiety and occurrence of symptoms.

▪ Describes several techniques for decreasing anxiety and managing stress.

▪ Identifies family/significant others as support network.

▪ States methods for contacting physician/therapist/agencies to meet needs.

▪ Describes importance of continuing use of medication, including dose, frequency, and expected/adverse effects.

▪ Discusses vulnerability in social situations and realistic ways to avoid problems.

▪ Verbalizes knowledge of responsibility for own actions and wellness.

▪ Describes plans to attend ongoing social support groups and rehabilitation/vocational training within limits.

▪ States alignment with aftercare facilities (e.g., home, board and care, halfway house).

Clients with chronic schizophrenia may never be entirely free of psychotic symptoms but can learn to manage them. Individuals who chronically experience hallucinations, especially the auditory command type, require closer supervision. The Client and Family Teaching box provides guidelines for client and family teaching in the management of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Online Resources

NARSAD, the Mental Health Research Association:

National Schizophrenia Foundation:

National Alliance on Mental Illness:

National Institute of Mental Health:

National Mental Health Association:

Schizophrenia

NURSE NEEDS TO KNOW

▪ Schizophrenia is a long-standing disorder with debilitating symptoms that challenges the client, family, health care workers, and the community.

▪ The client periodically experiences psychosis such as delusions and hallucinations, which may be frightening to the client and others.

▪ The client and others may need protection if hallucination is a command type that orders the client to harm or kill self or others.

▪ It is not appropriate to argue with the client about the reality of the delusion or hallucination, but one should be honest in sharing perceptions of reality.

▪ The client’s verbal response may be inconsistent with mood or affect, and further exploration may be warranted.

▪ When involving the client in hospital activities, realize that poor motivation and low energy levels may be caused by illness and sedative effects of medication, not laziness.

▪ How to engage the client/family in administering medication and monitoring side effects.

▪ What the therapeutic and nontherapeutic effects of typical and atypical antipsychotic medications are, as well as the benefits of the atypical drugs.

▪ The client must be observed for side effects and dangerous adverse effects of antipsychotic medication (e.g., anticholinergic/extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome).

▪ Current treatment must be reviewed to prevent adverse medication effects.

▪ What the state and federal laws regarding involuntary treatment, seclusion/restraint, and patient rights are.

▪ High amounts of stress and expectations can exacerbate symptoms, and very low stress and lack of challenge are also harmful.

▪ The client/family should focus on goals that are meaningful and realistic.

▪ The client with a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and substance abuse needs to have both issues addressed in treatment.

▪ The client with schizophrenia is more likely to be a victim of crime than a perpetrator, and the family needs assistance to plan for client safety without being overly restrictive.

▪ Institutional/psychosocial/family stressors must be recognized and they may exacerbate the client’s symptoms; the nurse must learn how to manage/prevent them.

▪ Schizophrenia is a chronic illness that can exhaust and frustrate a family, and family members need help in managing the client and illness.

▪ The family may need assistance with the client’s living arrangements, job placement (if capable), and managing day-to-day affairs.

▪ How to reinforce the importance of taking medication after discharge and of notifying physician/emergency support services if serious side effects occur.

▪ What the local chapters of mental health organizations, such as the National Alliance of the Mentally III (NAMI) are; these can provide education, advocacy, and social support for the family.

▪ Where group homes, community groups, and other resources that can help the client/family after discharge are; social work should be included in this effort.

▪ What current educational resources are available on the Internet and in local libraries.

TEACH CLIENT AND FAMILY

▪ Explain to the client/family that schizophrenia is a chronic disorder with symptoms that affect the person’s thought processes, mood, emotions, and social functions throughout the person’s lifetime.

▪ Teach the client/family about the primary symptoms of schizophrenia, delusions and hallucinations, and how to determine if they pose a threat or danger to the client or others.

▪ Explain to the client/family that although it is part of schizophrenia, psychosis (loss of reality) is not always present, and the client functions better in the absence of psychosis.

▪ Assist the family in developing a plan for dealing with the client during early signs of acute illness, which may prevent hospitalization.

▪ Instruct the client/family to recognize impending symptom exacerbation and to notify physician/hospital/emergency support services when the client poses a threat or danger to self or others and requires hospitalization.

▪ Teach the client/family about the importance of medication compliance and the therapeutic/nontherapeutic effects of antipsychotic medications.

▪ Tell the family that the client may not always have the energy or motivation to engage in family/social activities, which may be caused by the nature of the illness and the sedative effects of the medication.

▪ Instruct the family to have patience when interacting with the client, especially during times of stress/thought disturbances/fatigue.

▪ Inform the family that the client will be more responsive during more functional periods, such as when medications are working and the client is well rested.

▪ Ask the client/family to repeat what you have taught so that you will know what they have learned and what needs to be reinforced.

▪ Use different methods of teaching, because some clients may have more cognitive deficits than others and may benefit from alternative techniques.

▪ Teach the client/family to identify psychosocial/family stressors that may exacerbate symptoms of the disorder, and methods to prevent them.

▪ Instruct the client/family on the importance of continuing medication after discharge and to report any adverse/life-threatening effects.

▪ Help family members recognize that there are limits to what they can do for the client. Aspects of schizophrenia can be frustrating and exhausting to the family, and organizations can assist them.

▪ Educate the family about the educational and support services of the NAMI, and refer the family to the local chapter.

▪ Inform the client/family about local community groups and resources that can help the client manage daily affairs, find a job (if capable), and investigate living arrangements; include social work in this effort.

▪ Teach the client/family how to access current educational/therapeutic resources on the Internet and in the community.

CARE PLANS

Schizophrenia (All Types)

Disturbed Sensory Perception, 152

Disturbed Thought Processes, 157

Risk for Self-Directed Violence/Risk for Other-Directed Violence, 163

Social Isolation, 168

Impaired Verbal Communication, 171

Defensive Coping, 175

Disabled Family Coping, 179

Self-Care Deficit, 181

NOC

Cognitive Orientation, Thought Self-Control, Communication, Receptive Sensory Function, Hearing

NIC

Hallucination Management, Reality Orientation, Cognitive Restructuring, Communication Enhancement, Environmental Management

Change in the amount or patterning of incoming stimuli accompanied by a diminished/exaggerated/distorted/impaired response to such stimuli

ASSESSMENT DATA

Related Factors (Etiology)

▪ Neurobiologic factors (neurophysiologic, genetic, structural)

▪ Psychosocial stressors that are intolerable for the client and that threaten the client’s integrity and self-esteem

▪ Disintegration of boundaries between self and others and self and the environment

▪ Altered thought processes

▪ Severe/panic anxiety states

▪ Loneliness and isolation, perceived or actual

▪ Powerlessness

▪ Withdrawal from environment

▪ Lack of adequate support persons

▪ Inability to relate to others

▪ Critical/derogatory nonaccepting environment

▪ Low self-esteem

▪ Negative self-image/concept

▪ Chronic illness/institutionalization

▪ Disorientation

▪ Derealization/depersonalization

▪ Ambivalence

Defining Characteristics

▪ Client is inattentive to surroundings (preoccupied with hallucination).

▪ Startles when approached and spoken to by others.

▪ Talks to self (lips move as if conversing with unseen presence).

▪ Appears to be listening to voices or sounds when neither is present; cocks head to side as if concentrating on sounds that are inaudible to others.

▪ May act on “voices”/commands.

□ Attempts mutilating gesture to self or others that could be injurious.

▪ Describes hallucinatory experience.

□ “It’s my father’s voice, and he’s telling me I’m no good” (auditory).

□ “My mother just walked by the patio, and I saw her go behind that tree” (visual).

□ “I can feel my brain moving around inside my head” (somatic). “It’s turning into a transmitter” (coupled with a delusion).

□ “There are things crawling under my skin” (tactile).

▪ Has false perceptions hallucination when falling asleep ( hypnagogic) or waking from sleep ( hypnopompic).

▪ Misinterprets environment ( illusion).

□ Perceives roommate’s teddy bear as own dog.

□ Interprets a statue in the yard as brother.

▪ Describes feelings of unreality.

□ “I feel like I’m outside looking in, watching myself” (depersonalization).

□ “Everything around me became really strange just now” (derealization).

▪ May voice concern over normalcy of genitals/breasts/other body parts.

□ “My breasts are distorted.”

□ “My penis is abnormal.”

▪ Misinterprets actions of others.

□ “Sarah is coming at me with her tray; she wants to kill me.”

▪ Leaves area suddenly without explanation; may perceive environment as hostile or threatening.

▪ Has difficulty maintaining conversations; cannot attend to staff member’s responses and own hallucinatory stimuli at same time (confused/preoccupied).

▪ Interrupts group meetings with own experience, which is irrelevant to the situation/event and has symbolic, idiosyncratic meaning only for the client.

□ Demonstrates inability to make simple decisions.

□ Cannot decide which socks to wear or what foods to eat.

□ Uncertain whether to sit or stand during a group session (may indicate ambivalence or suspicion).

OUTCOME CRITERIA

The following criteria depend on severity of symptoms, client diagnosis, and prognosis. In some cases, staff expectations may be for modification of symptoms rather than for complete change of behavior.

▪ Client demonstrates the ability to focus relevantly on conversations with others on the unit.

▪ Ceases to startle when approached.

▪ Ceases to talk to self.

▪ Seeks staff when feeling anxious or when hallucinations begin.

▪ Seeks staff or other clients for conversation as an alternative to autistic preoccupation.

▪ Refrains from harming self and others.

▪ Relates decrease/absence of obsessions.

▪ No longer expresses feelings of self/environment as being unreal or strange.

▪ Describes body parts as being normal and functional.

▪ Demonstrates ability to hold conversation without hallucinating.

▪ Remains in group activities.

▪ Attends to the task at hand (group process, recreational/occupational therapy activity).

▪ States that hallucinations are under control.

□ “The voices don’t bother me anymore.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access