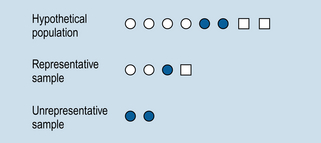

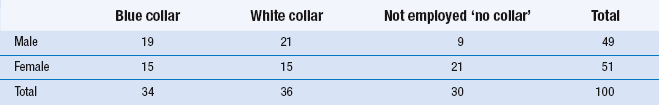

5 The specific aims of this chapter are to: 1. Define what is meant by sampling and representative samples. 2. Outline the relative advantages and disadvantages of commonly used sampling methods. 3. Discuss the relationship between sampling error and sample size. 4. Examine the concept of external validity for generalizing research findings to other settings. While this chapter will focus on the selection of the research participants in a study, many other things are also selected or sampled. These include: 1. The information to be collected by the researcher. 2. The procedures used for the collection of the information. 3. Where the research is conducted, e.g. in a field setting or in a structured research setting. Many researchers focus on the selection of the research participants as the key or only issue in maximizing the generalizability of their research and they do not pay enough attention to the other factors they are sampling or the context in which the research is being conducted. It is not at all unusual to see studies that employ large and sophisticated participant samples yet with only one or two highly selected clinicians involved in the research in perhaps only one health setting. While the study sample may be highly representative the context in which the research is conducted may not be and it may be that the researchers and clinicians involved in the study have a particularly unusual or idiosyncratic approach to their work that is not reflective of others. It is our contention that, in many qualitative studies, there is strong consideration of the research context and its impact upon the research findings. However, there is often less emphasis upon sampling of research participants. This impacts upon the ability to generalize the findings more broadly from the actual research participants to other groups. The population is the target group of individuals or cases in which the researcher is interested. Examples of valid study populations include: all English women under 25; all children with diagnosed spina bifida in the state of Alberta; all the students at a particular Australian college. The researcher defines the population to which he/she wishes to generalize. Note that a population need not consist of human participants or animal subjects. Objects or events can also be sampled, as shown in Table 5.1. Table 5.1 Examples of populations and samples As can be seen from Table 5.1, a population is an entire set of persons, objects or events which the researcher intends to study. A sample is a subset of the population. Sampling involves the selection of the sample from the population. The ultimate aim of all sampling methods is to draw a representative sample from the population. The advantage of a representative sample is clear: one can confidently generalize from a representative sample to the rest of the population without having to take the trouble of studying the rest of the population. If the sample is biased (not representative of the population) one can generalize less validly from the sample to the population. This might lead to quite incorrect conclusions or inferences about the population. This would mean that the results obtained in the study would not necessarily generalize to other studies using the same population. Figure 5.1 illustrates the concept of a representative sample. Figure 5.1 illustrates a hypothetical population composed of three different types of study participants or categories of participants. A representative sample is a precise miniaturized representation of the population. An unrepresentative or biased sample does not adequately represent the key groups or characteristics in the population, and this may lead to mistaken conclusions about the state of the population. More sophisticated examples involving more than two groups can be accommodated as shown in Table 5.2. We can see from Table 5.2 that, if our sample were to be representative regarding both sex and occupational status, in a sample of 100 people we would need 19 blue-collar males, 15 blue-collar females, and so on. Table 5.2 Distribution of percentages of gender and occupational variables in the general population Quota sampling still has a number of shortcomings: before it can be used, one has to know which population groups are likely to be important to a particular question and the exact proportions of the various groups in the population. Sometimes we may not know these proportions. Also, the members of the sample within the quotas are still incidentally chosen. The blue-collar males, for example, selected in a city centre on a weekday may still be quite different from those working elsewhere. However, quota sampling is better than simple incidental sampling.

Sampling methods and external validity

Introduction

What is sampled in a study

Basic issues in sampling

Population

Possible sample selection

All working podiatrists in a state

50 podiatrists selected for a study of job satisfaction

All working pathologists in a state

25 pathologists selected for detailed tax evaluation by an inspector

The temperature of a patient during a 24-h period

Hourly measurements of a patient’s temperature recorded by staff

Stuttering in a child’s speech

Number of stutters made during 5 min of reading a standard piece of material

All patients in a state with frontal lobe damage

30 patients with frontal lobe damage selected for evaluating a rehabilitation program

All surgical gauzes held by a given hospital

10 gauzes selected by a bacteriologist to test for sterility

Representative samples

Incidental samples

Quota sampling

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sampling methods and external validity

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access