S

Scleroderma

Description

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) is a disorder of the connective tissue characterized by fibrotic, degenerative, and occasionally inflammatory changes in the skin, blood vessels, synovium, skeletal muscle, and internal organs. Two types of scleroderma exist: limited cutaneous disease, which is more common, and diffuse cutaneous disease. Both forms are systemic with the degree and type of organ involvement and disease progression distinctly different.

Although symptoms may begin at any time, the usual age of onset is between 30 and 50 years, and most cases occur in women.

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of scleroderma is unknown. Immunologic dysfunction and vascular abnormalities are believed to play a role in the development of widespread systemic disease. Excessive production of collagen leads to progressive tissue fibrosis and occlusion of blood vessels. Proliferation of collagen disrupts the normal functioning of internal organs, such as the lungs, kidney, heart, and GI tract.

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations range from a diffuse cutaneous thickening with rapidly progressive and widespread organ involvement to the more benign limited cutaneous form. Signs of limited disease appear on the face and hands, whereas diffuse disease initially involves the trunk and extremities.

Clinical manifestations can be described by the acronym CREST: Calcinosis (painful calcium deposits in skin), Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysfunction (difficulty swallowing), Sclerodactyly (tightening of the skin on the fingers), and Telangiectasia (red spots on the hands, face, and lips).

Raynaud’s phenomenon (paroxysmal vasospasm of the digits) is the most common initial complaint in limited systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon may precede the onset of systemic disease by months, years, or even decades (see Raynaud’s Phenomenon, p. 531).

Symmetric painless swelling or thickening of the skin of the fingers and hands may progress to diffuse scleroderma of the trunk. In limited disease, skin thickening generally does not extend above the elbow or above the knee, although the face can be affected in some individuals. In more diffuse disease, the skin loses elasticity and becomes taut and shiny, producing a typical expressionless face with tightly pursed lips.

About 20% of people with scleroderma develop secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, a condition associated with dry eyes and dry mouth (see Sjögren’s Syndrome, p. 582). Dysphagia, gum disease, and dental caries can result. Frequent reflux of gastric acid also can occur as a result of esophageal fibrosis.

Lung involvement includes pleural thickening, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary artery hypertension, and pulmonary function abnormalities.

Primary heart disease consists of pericarditis, pericardial effusion, and cardiac dysrhythmias. Myocardial fibrosis resulting in heart failure occurs most frequently in people with diffuse scleroderma.

Renal disease was previously a major cause of death in diffuse scleroderma. Recent improvements in dialysis, bilateral nephrectomy in patients with uncontrollable hypertension, and kidney transplantation have offered hope to patients with renal failure. In particular, the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (e.g., lisinopril [Prinivil]) has had a marked impact on the ability to treat renal disease.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

Management of scleroderma offers no specific treatment. Supportive care is directed toward attempts to prevent or treat the secondary complications of involved organs. Physical therapy helps maintain joint mobility and preserve muscle strength. Occupational therapy assists the patient in maintaining functional abilities.

Drug therapy

No specific drugs or combinations of drugs have shown to be effective. Vasoactive agents are prescribed in early disease, and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine [Adalat, Procardia] and diltiazem [Cardizem]) are now a common treatment choice for Raynaud’s phenomenon. Other vasoactive drugs include reserpine (Serpasil) and losartan (Cozaar). Bosentan (Tracleer), an endothelin receptor antagonist, and epoprostenol (Flolan), a vasodilator, may assist in preventing and treating digital ulcers while improving exercise capacity and heart and lung dynamics.

Topical agents may provide some relief from joint pain. Capsaicin cream may be useful, not only as a local analgesic, but also as a vasodilator. Other therapies are prescribed to treat specific systemic problems, such as tetracycline for diarrhea resulting from bacterial overgrowth, and histamine H2-receptor blockers (e.g., cimetidine [Tagamet]) and proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole [Prilosec]) for esophageal symptoms. An antihypertensive agent (e.g., captopril [Capoten], propranolol [Inderal], methyldopa [Aldomet]) may be used to treat hypertension with renal involvement. Immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan], mycophenolate mofetil [CellCept]) may also be used to treat the disease.

Nursing management

Because prevention is not possible, nursing interventions often begin during hospitalization for diagnostic purposes. Emotional stress and cold ambient temperatures may aggravate Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Instruct patients not to have finger-stick blood testing because of compromised circulation and poor healing of the fingers. Teach the patient to protect the hands and feet from cold exposure and possible burns or cuts that might heal slowly. Smoking should be avoided because of its vasoconstricting effect. Lotions may help to alleviate skin dryness and cracking but must be rubbed in for an unusually long time because of skin thickness.

The patient must actively carry out therapeutic exercises at home. Reinforce the use of moist heat applications, assistive devices, and organization of activities to preserve strength and reduce disability. Sexual dysfunction resulting from body changes, pain, muscular weakness, limited mobility, decreased self-esteem, and decreased vaginal secretions may require sensitive counseling by the nurse.

Seizure disorders

Description

A seizure is a paroxysmal, uncontrolled electrical discharge of neurons in the brain that interrupts normal function. Seizures may accompany a variety of disorders, or they may occur spontaneously without any apparent cause.

Epilepsy is a condition in which a person has spontaneously recurring seizures caused by a chronic underlying condition. National trends show that incidence of epilepsy is increasing in older adults. Some populations are at higher risk to develop epilepsy, including those with Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and people with a parent who has epilepsy.

Pathophysiology

The most common causes of seizure during the first 6 months of life are severe birth injury, congenital defects involving the central nervous system (CNS), infections, and inborn errors of metabolism.

In people between 20 and 30 years old, a seizure disorder usually occurs as a result of structural lesions such as trauma, brain tumors, or vascular disease. After the age of 50 years, primary causes of seizure are stroke and metastatic brain tumors. Nearly 30% of all epilepsy cases are idiopathic. Some types of epilepsy tend to run in families, suggesting a genetic influence.

The etiology of recurring seizures (epilepsy) has long been attributed to a group of abnormal neurons (seizure focus) that undergo spontaneous firing. This firing spreads by physiologic pathways to involve adjacent or distant areas of the brain. The factor that causes this abnormal firing is not clear. Any stimulus that causes the cell membrane of the neuron to depolarize induces a tendency to spontaneous firing. Often the brain area from which epileptic activity arises is found to have scar tissue (gliosis). Scarring is believed to interfere with the normal chemical and structural environment of brain neurons, making them more likely to fire abnormally.

In addition to neuronal alterations, changes in the function of astrocytes may play several key roles in recurring seizures. Activation of astrocytes by hyperactive neurons is one of the crucial factors that predisposes neurons nearby to the generation of an epileptic discharge.

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations are determined by the site of the electrical disturbance. The preferred method of classifying epileptic seizures is presented in Table 59-6, in Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1420. This system is based on the clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) manifestations of seizures and divides seizures into two major classes, generalized and focal.

Depending on the type, a seizure may progress through several phases: (1) prodromal phase with signs or activity that precedes a seizure, (2) aural phase with a sensory warning, (3) ictal phase with full seizure, and (4) postictal phase, which is the period of recovery after the seizure.

Generalized seizures

Generalized seizures involve both sides of the brain and are characterized by bilateral synchronous epileptic discharge in the brain. In most cases the patient loses consciousness for a few seconds to several minutes.

Focal seizures

Focal seizures (formerly called partial seizures) begin in one hemisphere of the brain in a specific region of the cortex, as indicated by the EEG. They produce signs and symptoms related to the function of the area of the brain involved. For example, if the discharging focus is located in the medial aspect of the postcentral gyrus, the patient may experience paresthesias and tingling or numbness in the leg on the side opposite the focus.

Focal seizures are divided according to their clinical expressions into simple focal seizures (the person remains conscious) and complex focal seizures (the person has a change or loss of consciousness).

Focal seizures may be confined to one side of the brain and remain focal in nature, or they may spread to involve the entire brain, culminating in a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Complications

Status epilepticus is a state of continuous seizure activity or a condition in which seizures recur in rapid succession without return to consciousness between seizures. It can occur with any type of seizure. Status epilepticus is the most serious complication of epilepsy and is a neurologic emergency.

Perhaps the most common complication of seizure disorder is the effect it has on a patient’s lifestyle. Although attitudes have improved in recent years, epilepsy still carries a social stigma that can lead to discrimination in employment and educational opportunities. Transportation may also be difficult because of legal sanctions against driving.

Diagnostic studies

■ CT scan and MRI can rule out a structural lesion.

Collaborative care

Most seizures do not require professional emergency medical care because they are self-limiting and rarely cause body injury. However, if status epilepticus occurs, significant body harm occurs, or the event is a first-time seizure, medical care should be sought immediately. Table 59-8, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1423, summarizes the emergency care of the patient with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Drug therapy

Seizure disorders are treated primarily with antiseizure drugs (see Table 59-9, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1423). Medications generally act by stabilizing the nerve cell membranes and preventing the spread of the epileptic discharge.

The principle of drug therapy is to begin with a single drug based on patient age and weight with consideration of the type, frequency, and cause of seizure and increase the dosage until the seizures are controlled or toxic side effects occur. If seizure control is not achieved with a single drug, the drug dosage and timing or administration may be changed or a second drug may be added.

Surgical interventions for patients whose epilepsy cannot be controlled with drug therapy include anterior temporal lobe resection; extratemporal resection and lesionectomies; hemispherectomies; multilobar resections; and corpus callosum sections. These surgeries remove the epileptic focus or prevent spread of epileptic activity in the brain.

Nursing management

Goals

The patient with seizures will be free from injury during a seizure, have optimal mental and physical functioning while taking antiseizure drugs, and have satisfactory psychosocial functioning.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

The patient with a seizure disorder should practice good general health habits (e.g., maintaining a proper diet, getting adequate rest, exercising). Help the patient to identify events or situations that precipitate the seizures and give suggestions for avoiding them or handling them better.

Nursing care for a hospitalized patient or for a person who has had seizures as a result of metabolic factors should focus on observation and treatment of the seizure, education, and psychosocial intervention.

Patient and caregiver teaching

Patient and caregiver teaching

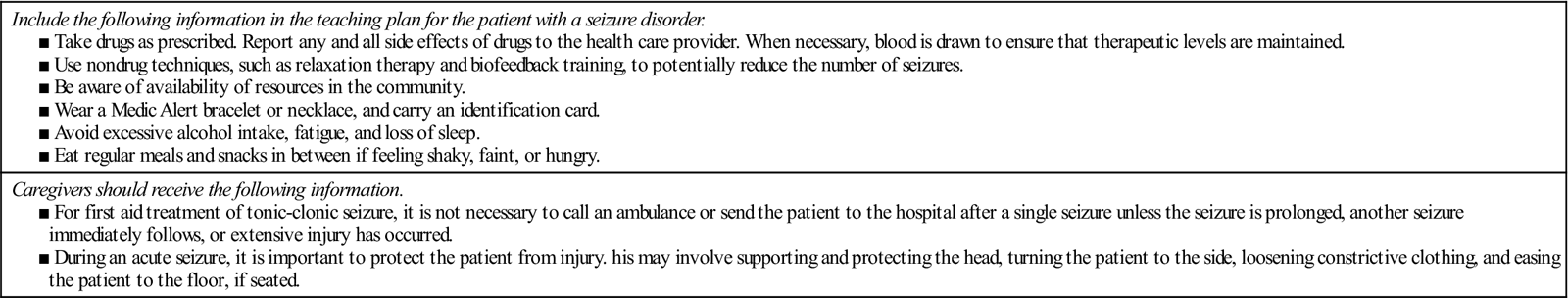

Prevention of recurring seizures is the major goal in the treatment of epilepsy. Drugs must be taken regularly and continually, often for a lifetime. You have an important role in teaching the patient and caregiver. Guidelines for teaching are shown in Table 75.

■ Ensure that the patient knows the specifics of the drug regimen and what to do if a dose is missed.

Table 75

Patient and Caregiver Teaching Guide

Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy

| Include the following information in the teaching plan for the patient with a seizure disorder. |

| Caregivers should receive the following information. |

Sexually transmitted infections

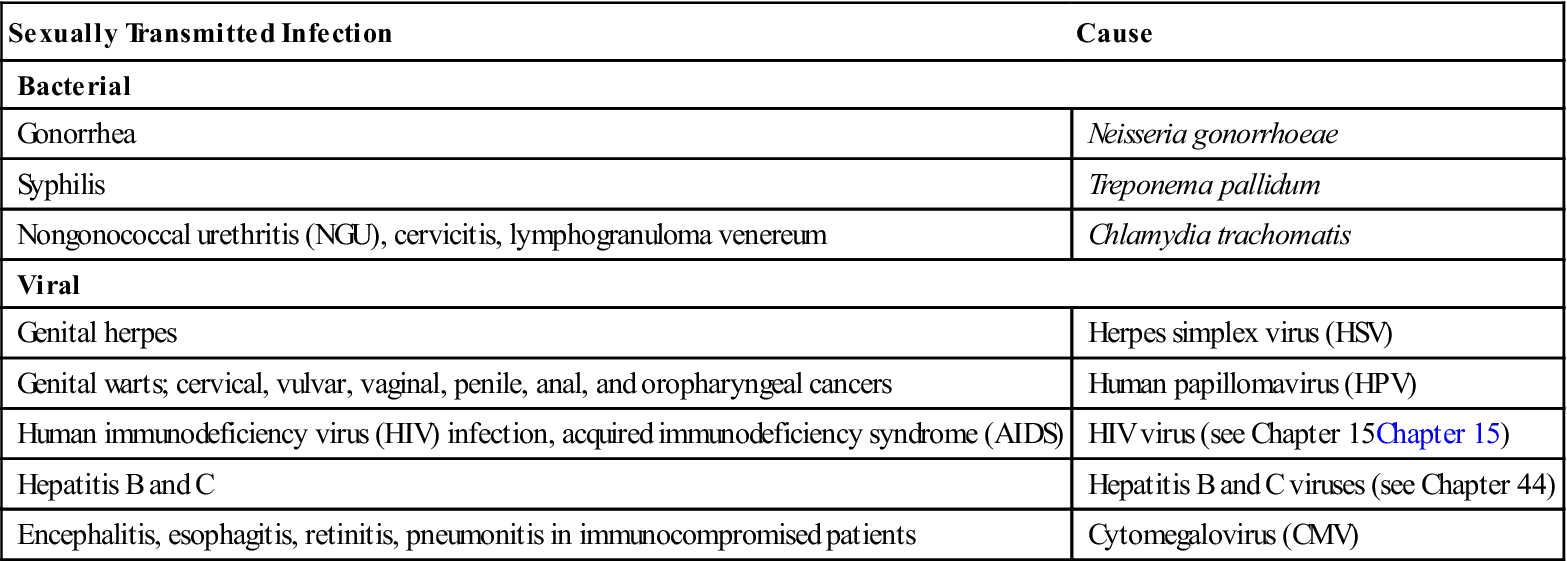

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are infectious diseases commonly acquired through sexual contact. Common infections that are transmitted sexually are listed in Table 76.

Table 76

Causes of Sexually Transmitted Infections

| Sexually Transmitted Infection | Cause |

| Bacterial | |

| Gonorrhea | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Syphilis | Treponema pallidum |

| Nongonococcal urethritis (NGU), cervicitis, lymphogranuloma venereum | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Viral | |

| Genital herpes | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) |

| Genital warts; cervical, vulvar, vaginal, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers | Human papillomavirus (HPV) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | HIV virus (see Chapter 15) |

| Hepatitis B and C | Hepatitis B and C viruses (see Chapter 44) |

| Encephalitis, esophagitis, retinitis, pneumonitis in immunocompromised patients | Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

Infections that are associated with sexual transmission can also be contracted by other routes, such as through blood, blood products, and autoinoculation. See Gonorrhea, p. 255; Syphilis, p. 611; Herpes, Genital, p. 309; Warts, Genital, p. 672; and Chlamydial Infections, p. 124.

An estimated 65 million people in the United States are currently infected with one or more STIs. In the United States, all gonorrhea and syphilis and, in most states, chlamydial infection must be reported to the state or local public health authorities. In spite of this requirement, there are many unreported cases of these infections.

Many factors are related to the current STI rates. Earlier reproductive maturity and increased longevity has resulted in a longer sexual life span. An increase in the total population has resulted in an increase in the number of susceptible hosts.

Nursing management: Sexually transmitted infections

Goals

The patient with an STI will demonstrate understanding of the mode of transmission and the risk posed by STIs, complete treatment and return for appropriate follow-up care, notify or assist in notification of sexual contacts about their need for testing and treatment, abstain from intercourse until infection is resolved, and demonstrate knowledge of safer sex practices.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

The diagnosis of an STI may be met with a variety of emotions, such as shame, guilt, anger, and a desire for vengeance. Provide counseling and encourage the patient to verbalize feelings. A referral for professional counseling to explore ramifications of an STI may be indicated.

All patients should return to the treatment center for a repeat culture from infected sites or serologic testing at designated times to determine effectiveness of treatment.

Emphasize to the patient with an STI the importance of certain hygiene measures. An important measure is frequent hand washing and bathing.

■ Bathing and cleaning of involved areas can provide local comfort and prevent secondary infection.

■ Douching may spread infection and is therefore contraindicated.

Patient teaching

Patient teaching

Be prepared to discuss “safe” sex practices with all patients, not only those who are perceived to be at risk. These practices include abstinence, monogamy with an uninfected partner, avoidance of certain high-risk sexual practices, and use of condoms and other barriers to limit contact with potentially infectious body fluids or lesions. A patient teaching guide related to the patient with a STI is presented in Table 53-9, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1272.

Initiate a discussion to assess the risk for contracting an STI. Questions to ask include number of partners, type of birth control used, use of condoms, history of an STI, use of IV drugs, and sexual preference. Do not assume that older people are not at risk, as an increasing number of older people are becoming infected.

Shock

Description

Shock is a syndrome characterized by decreased tissue perfusion and impaired cellular metabolism. The four main categories of shock are cardiogenic, hypovolemic, distributive, and obstructive.

Cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic shock occurs when either systolic or diastolic dysfunction of the pumping action of the heart results in reduced cardiac output (CO). The heart’s inability to pump the blood forward is classified as systolic dysfunction. The most common cause of systolic dysfunction is acute myocardial infarction (MI). Cardiogenic shock is the leading cause of death from acute MI. The patient experiences impaired tissue perfusion and cellular metabolism because of cardiogenic shock.

Studies helpful in diagnosing cardiogenic shock include laboratory studies (e.g., cardiac enzymes, b-type natriuretic peptide [BNP]), troponin levels), electrocardiogram (ECG), chest x-ray, and echocardiogram.

Hypovolemic shock

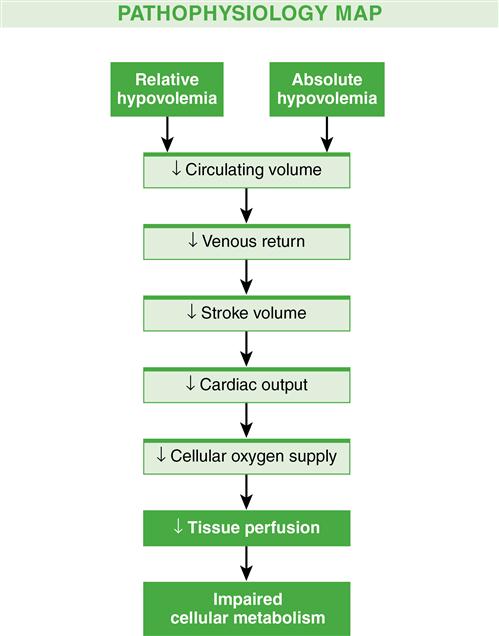

Hypovolemic shock occurs when there is a loss of intravascular fluid volume. The volume loss may be either an absolute or a relative volume loss.

In hypovolemic shock, the size of the vascular compartment remains unchanged while the volume of blood or plasma decreases. A reduction in intravascular volume results in decreased venous return to the heart, decreased preload, decreased stroke volume, and decreased CO. A cascade of events results in decreased tissue perfusion and impaired cellular metabolism, the hallmarks of shock (Fig. 14). A total blood loss of 15% to 30% results in a sympathetic nervous system (SNS)–mediated response that causes an increase in heart rate, CO, and respiratory rate and depth. If hypovolemia is corrected at this time, tissue dysfunction is generally reversible.

Laboratory studies include serial measurements of hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, electrolytes, lactate, blood gases, and central venous oxygenation (ScvO2), as well as hourly urine outputs.

Distributive shock (neurogenic, anaphylactic, septic)

Neurogenic shock

Neurogenic shock is a hemodynamic phenomenon that can occur within 30 minutes after a spinal cord injury at the fifth thoracic (T5) vertebra or above and last up to 6 weeks. The injury results in a massive vasodilation without compensation because of the loss of SNS vasoconstrictor tone. This leads to a pooling of blood in the blood vessels, tissue hypoperfusion, and ultimately impaired cellular metabolism.

In addition to spinal cord injury, spinal anesthesia can also block transmission of impulses from the SNS. Depression of the vasomotor center of the medulla from drugs (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines) may result in decreased vasoconstrictor tone of the peripheral blood vessels, resulting in neurogenic shock.

The patient in neurogenic shock may not be able to regulate body temperature. The inability to regulate temperature, combined with massive vasodilation, promotes heat loss. Initially, the patient’s skin will be warm because of the massive dilation. As the heat disperses, the patient is at risk for hypothermia.

The pathophysiology of neurogenic shock is described in Fig. 67-4, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1636.

Anaphylactic shock

Anaphylactic shock is an acute and life-threatening hypersensitivity (allergic) reaction to a sensitizing substance, such as a drug, chemical, vaccine, food, or insect venom. The reaction quickly causes massive vasodilation, release of vasoactive mediators, and an increase in capillary permeability.

Septic shock

Septic shock is the presence of sepsis (systemic inflammatory response to infection) with hypotension despite fluid resuscitation along with the presence of inadequate tissue perfusion resulting in tissue hypoxia. The main organisms that cause sepsis are gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Parasites, fungi, and viruses can also lead to the development of sepsis and septic shock. The pathophysiology of septic shock is described in Fig. 67-5, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1638.

■ Clinical manifestations include an initial decreased ejection fraction with the ventricles dilating so as to maintain stroke volume. The ejection fraction typically improves and the ventricular dilation resolves over 7 to 10 days. Persistence of a high CO and a low systemic vascular resistance (SVR) beyond 24 hours is an ominous finding and is often associated with an increased development of hypotension and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (see Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, p. 614).

Obstructive shock

Obstructive shock develops when a physical obstruction to blood flow occurs with a decreased CO. This can be caused from a restriction to diastolic filling of the right ventricle because of compression (e.g., cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, superior vena cava syndrome). The pathophysiology of obstructive shock is described in Fig. 67-6, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1638.

Stages of shock

The shock continuum begins with the initial stage that occurs at a cellular level and is usually not clinically apparent. Metabolism changes at the cellular level from aerobic to anaerobic cause lactic acid buildup. The removal of lactic acid by the liver requires oxygen, which is unavailable because of decreased tissue perfusion.

Shock is categorized into three clinically apparent but overlapping stages: compensatory stage, progressive stage, and irreversible stage.

Compensatory stage

In the compensatory stage, the body activates neural, hormonal, and biochemical mechanisms to overcome the increasing consequences of anaerobic metabolism and maintain homeostasis.

If the cause of shock is corrected at this stage, the patient recovers with few or no residual effects. If the cause of shock is not corrected and the body is unable to compensate, the patient goes on to the progressive stage of shock.

Progressive stage

The progressive stage of shock begins as compensatory mechanisms fail. Continued decreased cellular perfusion and resulting altered capillary permeability are the distinguishing features of this stage. The patient may have diffuse and profound edema (anasarca). In this stage, aggressive interventions are necessary to prevent the development of MODS.

Irreversible stage

In the final stage of shock, the irreversible stage, decreased perfusion from peripheral vasoconstriction and decreased cardiac output exacerbate anaerobic metabolism. The loss of intravascular volume worsens hypotension and tachycardia and decreases coronary blood flow. Cerebral blood flow cannot be maintained, and cerebral ischemia results.

Diagnostic studies

See Table 67-3, Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1635, for further information.

Collaborative care: General measures

Critical factors in management are early recognition and treatment. Prompt intervention in the early stages may prevent the decline to the progressive or irreversible stage. Successful management includes (1) identification of patients at risk for shock; (2) integration of the patient’s history, physical examination, and clinical findings to establish a diagnosis; (3) interventions to control or eliminate the cause of the decreased perfusion; (4) protection of target and distal organs from dysfunction; and (5) provision of multisystem supportive care.

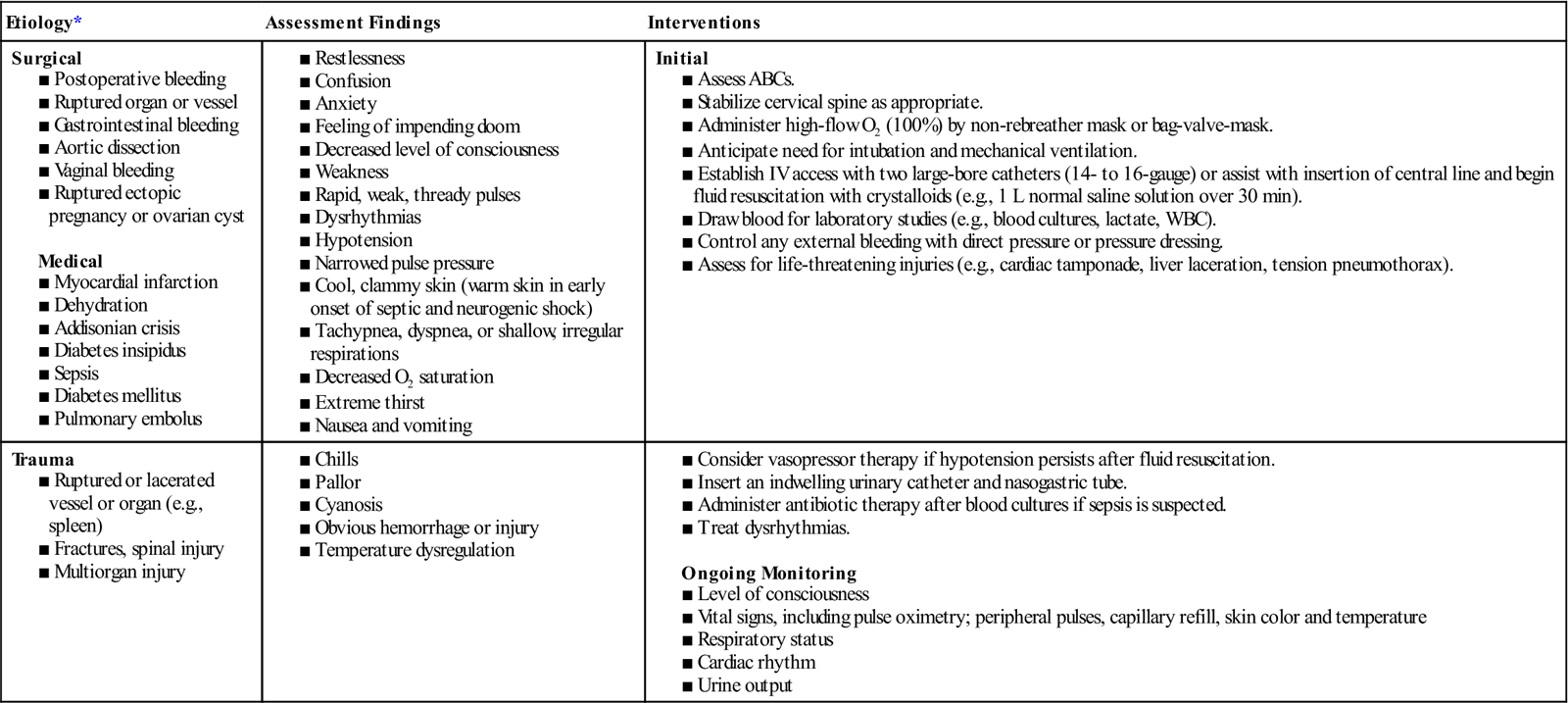

Emergency care of the patient in shock is presented in Table 77. General management strategies begin with ensuring that the patient has a patent airway. Once the airway is established, with either a natural airway or an endotracheal tube, oxygen delivery must be optimized.

■ Supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation may be necessary to support the delivery of oxygen to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation of at least 90% (PaO2 greater than 60 mm Hg) to avoid hypoxemia (see Artificial Airways: Endotracheal Tubes, p. 679, Oxygen Therapy, p. 717, and Mechanical Ventilation, p. 711). The mean arterial pressure and circulating blood volume are optimized with fluid replacement and drug therapy (see Table 67-8 in Lewis et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1643).

Table 77

*See Table 67-1 in Lewis, et al.: Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1632, for additional etiologies of shock.

Collaborative care: Specific measures

In addition to general management of shock, there are specific interventions for different types of shock (Table 78).

Table 78

| Oxygenation | Circulation | Drug Therapies | Supportive Therapies |

| Cardiogenic Shock | |||

| Hypovolemic Shock | |||

| Septic Shock | |||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||