CHAPTER 2 Role of the interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary team

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to:

INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes the contemporary roles of health professionals in caring for individuals with a chronic illness and/or disability. Every health professional plays an important role in the interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary team. The chapter also discusses the scope of practice implemented by other health professionals through a team approach to support a person with a chronic illness and/or disability. The very nature of chronic illness and/or disability demands that many health disciplines work collaboratively to manage the complexity and variety of health issues that arise.

The terms ‘interdisciplinary’ and ‘multidisciplinary’ are often used interchangeably in the literature to denote the group of health professionals who comprise ‘the team’ responsible for the provision of care in chronic illness and/or disability. Neal (2004) does, however, distinguish between the two, essentially based on the approach to care employed by the team, which is worth noting. In a multidisciplinary team, it is most likely that the approach to care will be discipline focused (Neal, 2004). Here the health professionals largely work within their discipline base, independently of other health professionals, in determining goals in collaboration with the patient and family. The alternative approach of an interdisciplinary team comprises health professionals from several different disciplines who work collectively to identify and resolve issues through mutually agreed upon goals with the patient and family (Morris & Edwards, 2006). Overall it needs to be recognised that regardless of the label applied to the approach used, team meetings are used to share information and discuss possible solutions to achieving an optimal outcome for patients and their families (Morris & Edwards, 2006).

This chapter describes the roles of the dietitian, general practitioner, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, speech pathologist and social worker in an interdisciplinary team.

Morris T.L., Edwards L.D. Family caregivers. In Lubkin I.M., Larsen P.D., editors: Chronic illness. Impact and interventions, (6th edn)., Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 2006.

Neal L.J. Settings of chronic care. In: Neal L.J., Guillett S.E., editors. Care of the adult with chronic illness or disability: a team approach. St Louis: Elsevier, 2004.

ROLE OF THE DIETITIAN

A dietitian’s primary aim is to improve individual and community health and wellbeing through food. They assist people to understand the relationship of food to health and how to make healthy food choices. Nutritional advice is in strong demand, given the increase in the incidence of diet-related diseases, which often lead to chronic disease and disability (Wahlqvist, 2002). A dietitian uses a range of techniques to assess nutritional status, identify specific problems, counsel for better health outcomes and plan and evaluate for patient care.

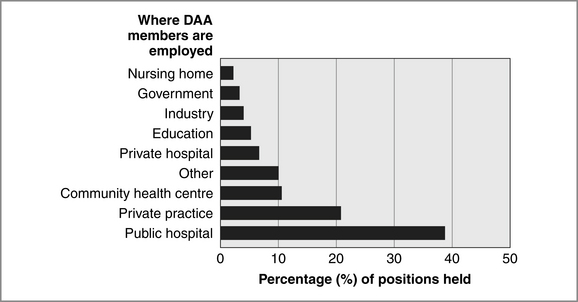

Dietitians work in a range of public and private settings and with people of all ages. They may work as clinical dietitians, as public health nutritionists, as nutrition service managers or private practitioners. Figure 2.1 shows where APDs are employed in Australia.

A clinical dietitian works with people with particular medical conditions and is responsible for all aspects of nutritional care and nutritional intervention. This may include assessing needs for therapeutic or special diets. It may also include making recommendations to medical staff for biochemical tests, nutrition supplements and modes of feeding such as tube feeding and total parenteral nutrition. Nutrition education for patients and their families is an important aspect of a dietitian’s role in any setting.

NUTRITIONAL STANDARDS OF REFERENCE

The dietitian uses the following nutritional standards of reference to analyse individual diets.

NUTTAB 2006 Australian food composition tables

Food composition tables are used to convert information about food intake to nutrient intake (Wahlqvist, 2002). The composition of foods, Australia series is regularly updated by the Australian and New Zealand Food Authority. The NUTTAB 2006 Australian food composition tables contain updated food composition data for approximately 1750 common foods and 29 nutrients and are useful for those wanting summary nutrient data for commonly consumed foods.

Nutrient Reference Value

According to Wahlqvist (2002), the National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) says that Recommended Dietary Intakes are the range of levels of intake of essential nutrients considered to be adequate to meet the known nutritional needs of practically all healthy people, based on available scientific knowledge. In 2005 the NH&MRC endorsed the Nutrient Reference Value as a more specific nutrient value to identify the average requirements needed by healthy individuals.

Australian Dietary Guidelines

The dietitian will also use the Australian Dietary Guidelines as a practical way of informing people about the general principles of healthy eating. These guidelines, first developed in 1981 and revised by the NH&MRC in 1992, are intended to be used as a coherent set of advice or information.

Nutritional anthropometric reference values

Height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-height ratios and body mass index (BMI) are the most common anthropometric tools used to assess growth and the level of energy store. In children there is an expected range in variation, often referred to as a percentile. For example, the 50th percentile represents the median weight (or height) as the value below which the heights and weights of 50% of healthy children are expected to fall. For adults, BMI (weight in kilograms divided by (height in metres)2) is used as a measure of energy stores. It is the most commonly used indicator of nutritional status (Wahlqvist, 2002).

CONCLUSION

A dietitian will make a nutritional assessment by:

This process does not happen in isolation and the dietitian is an integral part of the interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary team that is working together to achieve the best possible health outcomes for every individual. All team members play an important role in observing and communicating with one another for signs of progress or signs of complications. This observation and communication between team members is an integral component to achieving optimised health outcomes.

Australian and New Zealand Food Authority (2006) The NUTTAB 2006 Australian Food Composition Tables. Accessed 10 August 2007 from http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/monitoringandsurveillance/nuttab2006/

Dietitians Association of Australia (2007a) Becoming a Dietitian. Accessed 10 August 2007 from http://www.daa.asn.au/index.asp?pageID=2145833487

Dietitians Association of Australia (2007b) Working and Studying. Accessed 10 August 2007 from http://www.daa.asn.au/index.asp?pageID=2145833452

National Health, Medical Research Council (1992) Australian Dietary Guidelines. Accessed 10 August 2007 from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/dietsyn.htm

The National Health, Medical Research Council (2005) Nutrient Reference Value. Accessed 10 August 2007 from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/_files/n35.pdf

Wahlqvist M., editor. Australia and New Zealand Food and Nutrition. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2002.

ROLE OF THE MEDICAL PRACTITIONER

Primary care medicine is also funded in different ways. In Australia until 1999, the general practitioner (GP) was funded on a fee-for-service basis only, and no substitution of services by other health professionals on behalf of the GP was permitted. (These rules are identical to those related to consultation reimbursement currently in force (Medicare Australia, 2007).) That is, the GP had to see the patient and deliver the service personally in order to attract government-supported payments. Practice staff could not render the service for them. This is in sharp contrast to the UK model, where the general practice is the unit of care, and the GP heads a team of several health professionals who provide the care. The practice is paid a per capita fee to deliver primary care services to a defined group of patients, with the fee increasing if certain health targets (e.g. a percentage of patients immunised for influenza annually) are met. Teamwork in this setting is clearly encouraged (Weller & Maynard, 2004).

Since 1999, there has been a marked shift towards multidisciplinary care. Health planners have recognised that comprehensive care cannot be delivered by one health practitioner in isolation, and funding models have shifted to accommodate this. Health outcomes are better when patients are cared for in teams, with purposive planning of the care. For example, in the care of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, patients have improved function, are more independent and have better quality of life when they are treated by multidisciplinary teams (Tieman et al, 2006). Similarly, diabetic patients who have comprehensive care by a general practice-based team have improved outcomes, to the point that their risk of an adverse vascular event such as a heart attack or stroke in the next five years actually falls by 25% over two years (Ackermann & Mitchell, 2006).

Following are two examples of the way such programs can work. In Case Study 2.1 a multidisciplinary care program has been put in place within a rural general practice for diabetic patients. The features of this model are that every diabetic patient is offered the service, and programmed recall is arranged every three months. The nurse works to a plan to review the patient, advising the doctor of findings to be reviewed. The doctor then arranges for individualised, ongoing care (Ackermann & Mitchell, 2006). In Case Study 2.2, case conferences and care planning take place between the team at a specialist inpatient stroke unit and all persons are involved in the early discharge of the patient to home. The participants all contribute to the care planning, the tasks are allocated clearly and there is a definite follow-up plan to ensure all planned treatments are carried out (Fjaertoft et al, 2004; Fjaertoft, Indredavik & Lydersen, 2003; Fjaertoft et al, 2005; Indredavik et al, 2000).

CASE STUDY 2.1

INTRA-PRACTICE MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE (ACKERMANN AND MITCHELL, 2006)

Setting: Regional Australian town, district population 25,000

Patients: All diabetic patients of the practice n = 700; 404 participated

Multidisciplinary team members: GP, practice nurse, visiting diabetic educator, visiting dietitian

Outcomes: Population improvements in abdominal circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL and LDL cholesterol, and five-year risk of cardiovascular events, proportion of patients suffering severe hypoglycaemia in last 12 months, and proportion of foot lesions; proportion of patients at or below recommended blood pressure and cholesterol readings increased (all p<0.05) over two years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree