Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings in Nursing Practice

Kaye Bultemeier

Nursing is both a science and an art. The uniqueness of nursing, like that of any other science, lies in the phenomenon central to its focus. Nurses’ long-established concern with people and the world they live in is a natural forerunner of an organized abstract system encompassing people and their environments. The irreducible nature of individuals is different from the sum of the parts. The integralness of people and environment that coordinate with a multidimensional [later changed to pandimensional] universe of open systems points to a new paradigm: the identity of nursing as a science. The purpose of nurses is to promote health and well-being for all persons wherever they are. The art of nursing is the creative use of the science of nursing for human betterment.

History and Background

First introduced by Rogers in 1970, the Rogerian model is an abstract system of ideas from which to approach the nursing care of unitary human beings. Her ideas were revolutionary and challenged nursing to approach care from a wholistic and dynamic worldview.

Within the Science of Unitary Human Beings (SUHB), assumptions regarding the nature of nursing offer further elaboration. First, nursing science is an organized body of abstract scientific knowledge that develops from research and analysis. This science of nursing helps explain the human experience (Rogers, 1970). Second, Rogers contends that nursing is a learned profession and therefore must be based on solid scientific information. Third, Rogers’ theoretical model places an emphasis on “the essentials, potentials, and possibilities that exist within the wholeness of life” (Cowling, 2001, p. 37). Fourth, formulated knowledge is to be used creatively for human betterment (Rogers, 1970). Additional theoretical understanding and elaboration is needed to assist in the understanding of theabstract model introduced by Rogers. Within SUHB, the following are understood to be fundamental:

Overview of Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings

Within this model, human beings are conceptualized as dynamic, constantly evolving energy fields, rather than as homeostatic beings. Variation is expected and embraced within this homeodynamic perspective. The human field and the environmental field are constantly exchanging energy. There are no boundaries or barriers to inhibit energy flow between fields (Rogers, 1970). “The human being openly participates in energy transformation with the environment creating mutual change” (Leddy, 2004, p. 16). The following concepts are inherent to the model and provide additional clarity regarding the Rogerian SUHB.

Unitary Human Being

A unitary human being is “an irreducible, indivisible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics that are specific to the whole and which cannot be predicted from knowledge of the parts” (Rogers, 1992, p. 27). The life process of the unitary human being is one of wholeness and continuity as well as dynamic and creative change.

Environment

The environment is “an irreducible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and integral with the human field” (Rogers, 1992, p. 27). Manifestations emerge from this field and are perceived. Figure 13-1 is an illustration of the coexistence or integrality of the human/environmental fields.

Nursing

The focus of nursing is the care of people within their life process and the lived experience. According to Rogers (1970), “Professional practice in nursing seeks to promote symphonic interaction between human and environmental fields, to strengthen the integrity of the human field, and to direct and redirect patterning of the human and environment fields for realization of maximum health potential” (p. 122). The nurse participates knowingly with the patient and the goal of nursing is human betterment.

Health

The concepts of health and illness are understood as pattern manifestations. The manifestation of health emerges from the mutual, simultaneous patterning process of the human/environmental fields. Pattern manifestation is an expression of the process of life as defined by individuals and their cultures (Rogers, 1970). Therefore, what we know as health and illness are considered continuous expressions or manifestations of the life process in Rogers’ framework.

There are four major concepts of the framework. These concepts describe characteristics of manifestations of the person and environmental mutual process. The major concepts of the framework are as follows:

Pattern

Pattern identifies individuals and reflects their wholeness. Pattern is defined as the distinguishing characteristic of an energy field that is perceived as a single wave. Rogers (1986) clarifies that pattern is “an abstraction” that “gives identity to the field” (p. 5). Patterning “is the dynamic or active process of the life of the human being” (Alligood & Fawcett, 2004, p.11).

Energy Field

Energy is the “potential for process, movement, and change” (Leddy, 2003, p. 21). The energy field is the conceptual boundary of all that is, the living and the nonliving. The energy field “provides a way to perceive people and their environment as irreducible wholes” (Rogers, 1986, p. 4).

Pandimensionality

Pandimensionality is defined as “a nonlinear domain without spatial or temporal attributes” (Rogers, 1990, p. 7). The universe encompasses infinite dimensions, providing an understanding of nonlocality, acausality, and unpredictability (Butcher, 2006).

Openness

The human field and the environmental field are constantly in mutual process. There are no boundaries or barriers to inhibit energy flow between fields (Rogers, 1970). “The human being openly participates in energy transformation with the environment creating mutual change” (Leddy, 2004, p. 16).

The complexity, and yet simplicity, of these paradigm shifting ideas preceded current scientific understanding by several decades. Rogers used her extensive knowledge and diverse educational background to articulate a revolutionary way of viewing the human experience.

Homeodynamic Principles

Rogers’ principles of homeodynamics provide a way of describing, explaining, and envisaging a wide range of perceivable person/environment processes involving change and growth (Rogers, 1986, 1990, 1992). The principles are theoretical assertions that were first proposed by Rogers (1970) as “an ordered arrangement of rhythms characterizing both the human field and the environmental field that undergoes continuous dynamic metamorphosis in the human-environment process” (p. 101) and were later articulated by Rogers (1992) and Phillips (2010). The principles describe the nature of the human/environmental process as follows:

Theories for Practice

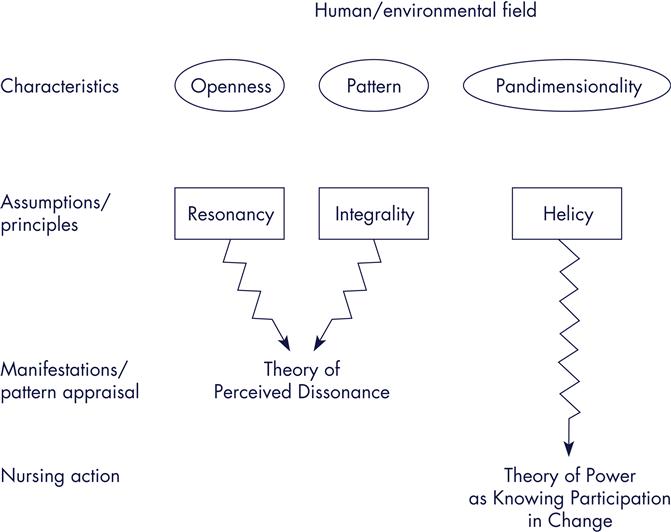

The Rogerian model provides the abstract philosophical framework from which to view the unitary human being and the environmental field. Though SUHB served as a framework for hundreds of research projects over the past 50 years, recent works have clarified application of SUHB for nursing practice. Rogers states that the nature of nursing is based on theoretical knowledge that guides nursing practice (1970). Barrett’s theory of power (1990b, 1998, 2000, 2010), Butcher’s pattern portrait (2006), and Cowling’s unitary pattern appreciation (1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2005) have proposed practice methods for the visionary work of Martha Rogers that guide both research and practice. Emerging from Rogers’ model are many theories that explain human phenomena and direct nursing practice. Cowling (2004) observes, “Research and practice are ‘theory-in-action,’ and practice informs research and theory building” (p. 206). The Rogerian model, with its implicit assumptions, provides broad principles that conceptually direct theory development (Figure 13-2). Theory emerges from each of the principles and unites the art with the science (Alligood, 2002). Some of the midrange theories that have emerged from the SUHB and provide understanding and guidance in the practice of nursing based on Rogers’ homedynamic framework include the Theory of Perceived Dissonance derived by Bultemeier (1997) from the Rogerian model, which provides a theoreticalperspective for exploring situations of varying resonancy as manifested in health care concerns. This theory emerges from the principles of resonancy and integrality and proposes that resonancy is altered periodically and rhythmically during the evolution of energy fields. The perception of dissonance during the rhythmical evolution of the human/environmental field is proposed. During episodes of varying resonancy, the human/environmental field manifestations may be perceived as nonharmonic and as uncomfortable or unsettling to the person; thus the person may view himself or herself as out of harmony, or ill (see Figures 13-1 and 13-2).

Theory of Power as Knowing Participation in Change

The theory proposed by Barrett (1986, 2010), Power as Knowing Participation in Change, emerges from the principle of helicy within the Rogerian model (see Figure 13-2). The theory proposes that as knowledge increases, so does the capacity to participate knowingly. Furthermore, the theory proposes the capacity of human beings to pattern their human/environmental fields. Barrett (2010) explains, “Following the testing and research of the theory and measurement instrument, a practice methodology was developed and the health patterning practice model was initiated” (p. 47). Patterning manifests via the nurse and client patterning process. Barrett (2000) describes power as being aware of what one is choosing to do, feeling free to do it, and doing it. She identifies power as a relative state characterized by the momentary continuously changing pattern. Power is a relative trait characterizedby “the more consistent organization of the human and environmental field pattern” (Barrett, 1986, p. 174). She specifies that as the person is knowledgeable of his or her pattern manifestations, meaningful participation in the patterning process occurs. Barrett’s theory is used widely by nurses around the world. And in 2010, the volume 23, number 1 issue of Nursing Science Quarterly celebrated Barrett’s power theory and Rogers’ SUHB. Barrett (2010) told her story of the development of her power theory in that special issue also pointing out “what’s new and what’s next” (p. 47).

Theory of Self-Transcendence

The Theory of Self-Transcendence by Gulliver (2007) describes the process occurring at the end-of-life. The theory proposes continuously fluctuating imagery boundaries over past, present, and future. With self-transcendence the boundaries become less distinct. The theory further articulates the infinite possibilities for this transition.

Critical Thinking in SUHB Nursing Practice

Critical thinking is a process of conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information gathered from or generated by observation, experience, reflection, reason, and communication as a guide to belief and action. Within Rogers’ model, a critical thinking process was developed that specifies three components: pattern appraisal, mutual patterning, and evaluation (Barrett, 2000; Cowling, 1990, 2004). The activities associated with these components are occurring simultaneously and continuously throughout the care of the client. This is a simultaneous, integral, and constantly evolving process. The life process possesses its own unity and is inseparable from the environment.

Pattern Appraisal

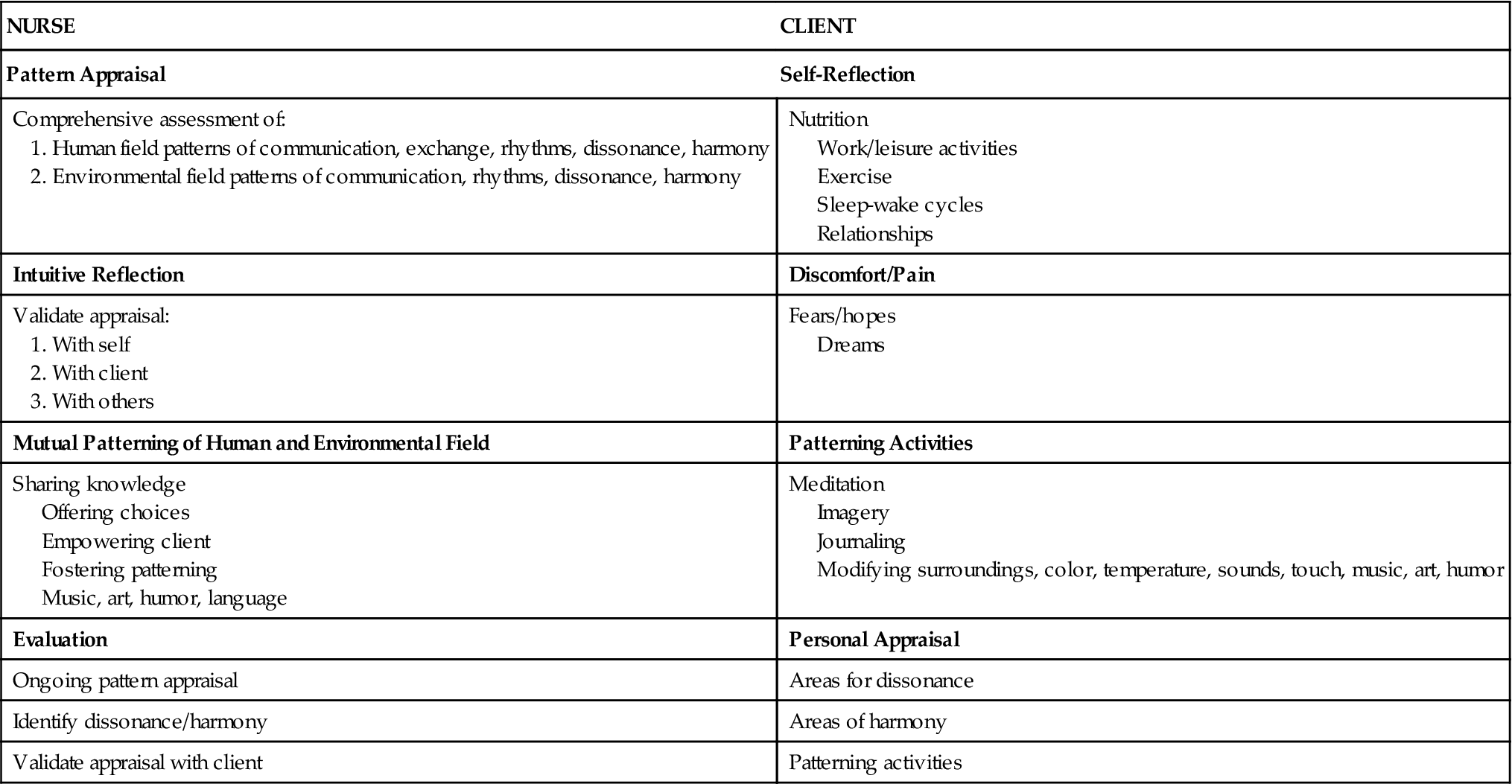

Pattern appraisal requires the identification of pattern manifestations that reflect the whole. Pattern appraisal is integral to the provision of care to unitary human beings. Table 13-1 outlines the critical thinking of the nurse and the self-reflection by the client. Nursing within Rogers’ model focuses on the manifestations that emerge from the mutual human/environmental field process. The meeting of the art and science of nursing is vital to the entire process of caring for the client from a Rogerian framework. Pattern appraisal is a comprehensive assessment that incorporates cognitive input, sensory input, intuition, and language. Intuitive knowledge is gained from both the client and the nurse. The nurse accompanies the client in focusing on personal patterns and rhythms. Identification of emerging pattern manifestations throughout the provision of care allows for a departure from the linear cause-and-effect approach and uses an evolutionary approach. The nurse and client gain awareness of rhythmical fluctuations and their associated manifestations. A change in pattern of the human field and the environmental field is propagated by waves. The manifestations of field patterning that emerge are perceivable events (Rogers, 1992). The identification of patterns that characterize a phenomenon provides knowledge and understanding of the human experience and provides the basis for the care, which results (Rogers, 1970).

TABLE 13-1

Critical Thinking in Rogers’ Model

Patterning “is the dynamic or active process of the life of the human being” that is “accessible to the senses” (Alligood & Fawcett, 2004, p. 11). Pattern information encompasses “phenomena that are categorized as physical/psychological, mental/emotional, social/cultural, and spiritual/mystical” (Cowling, 2005, p. 95). Wholistic pattern appraisal tools are necessary for application of the Rogerian model to the provision of nursing care to the unitary human being.

The nurse incorporates information gained from traditional measurement tools used to care for patients into the wholistic pattern appraisal. All conventional information gained such as vital signs, lab results, biopsy reports, and radiographic reports are integrated into the pattern appraisal and acknowledged as manifestations of the whole. Nurses are asked to incorporate knowledge gained from the use of their senses for the wholistic pattern appraisal. Consequently sight, smell, touch, hearing, and taste all contribute information of emergent patterns. Knowledge gained is via cognitive, sensory, intuitive understanding as well as language. Pattern appraisal includes perceivable rhythms of sleep/wake, mood, pain, movement, and nutrition. Patterning activities are based on probabilistic outcomes as they emergefrom the appraisal of pattern evolution. Emergent human environmental rhythms and patterns are manifestations of the whole; that is, the mutual process of human beings and their environment.

Cowling (2005) provides direction for nurses to study unitary human phenomena such as he has developed for nursing of despairing women. His guidelines assist the assessment and care process. He contends that all pattern appreciation must include the features of being synoptic—viewing together what normally is viewed apart, participatory and collaborative and transformative or reaching for the essence. Butcher (1998) identified additional pattern appraisal methods that include Human Field Motion Tool, Index of Field Energy, Human Field Image Metaphor Scale, Person-Environment Participation Scale, Perceived Field Motion Scale, and the Human Field Rhythms scale.

An important component of the appraisal process involves the work of the client to center and reflect on his or her personal pattern and on the pattern of those with whom he or she shares life. Bultemeier (1997) introduced the use of photographs and written narrative to assist in pattern identification. Pattern appraisal includes multiple lifestyle rhythms, such as nutrition, work, exercise, pain, anger, depression, sleep-wake cycles, and safety. A method for categorizing rhythmicities is by the use of criteria developed by Kim and Moritz (1982). These rhythms include the following: (1) exchanging (eating, elimination, breathing, giving, and receiving); (2) communication (verbal and nonverbal); and (3) relating (spacing, touching, eye contact, belonging, and referencing). During the appraisal, special attention is given to rhythms of pain and discomfort or to areas about which the client is uncomfortable or concerned (Cowling, 1990). Wholistic pattern appraisal methods and practice applications such as the following continue to be developed and refined for human betterment:

• Barrett (1990a,b, 1998, 2000, 2010): Health Patterning

• Butcher (1998, 2006): Pattern Portrait

• Cowling (1990, 1997, 2005): Pattern Appreciation

• Cowling and Swartout (2011): Life Patterning for Healing Praxis

• Greene and Greene (2012): Guided Imagery

• Gueldner, Michel, Bramlett, et al. (2005): the Well-being Picture Scale

• Johnston (1994): Human Field Image Metaphor Scale

• Malinski (2012): Unitary Rhythm of Dying-Grieving

• Willis and Griffith (2010) and Willis & Grace (2011): Healing Patterns

• Wright (2010): Power and Trust

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree