4.1 How to search the literature

Performing literature searches is a skill well worth acquiring and honing. A brief overview is provided here to help you get started and further resources are listed at the end of the chapter. This section does not aim to teach you to use a particular search engine or database; but instead outlines the principles of good searching so you are better able to learn how to use the tools available to you.

4.1.1 Defining search terms

You already have your research question and from this question you can determine your key search terms. The more focused and precise the question, the more specific you will be able to make your search.

Your question can be formulated using the mnemonic PICO (Richardson et al. 1995), where:

| P | = | Problem or patient: What is the problem or patient group you are interested in? |

| I | = | Intervention or exposure: What is being done to the patient or what possible exposure is of interest? |

| C | = | Comparison: What is the usual treatment or factor you wish to compare with? |

| O | = | Outcome: What is the desired outcome of the treatment? |

For example:

Does bariatric surgical treatment improve weight loss in obese patients compared to lifestyle advice?

P: Obesity

I: Bariatric surgery

C: Lifestyle advice

O: Weight loss

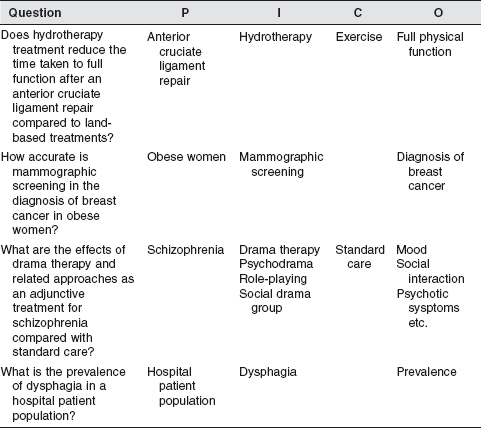

All the terms you list under each heading will be your search terms and you may have more than one. In this example I could add ‘gastric banding’ and ‘gastric bypass’ to ‘I’ search terms. Table 4.1 shows further examples with different types of question, and that for some types of research not all categories are required. When deciding on your search terms within each category think about the usual terminology, common alternatives, and alternative spellings for the most thorough searching.

Table 4.1 Further examples of search term analysis using the PICO system.

4.1.2 Identify suitable sources of evidence

Virtually all papers published in journals are indexed on to electronic bibliographic databases, which can be searched in order to retrieve papers that match search criteria. There are two main types of bibliographic databases – secondary and primary.

4.1.2.1 Secondary databases

Secondary databases contain systematic reviews, summaries, guidelines and consensus statements. They all, in one way or another, summarise the available original research. The National Library for Health (NLH) (see Section 4.3.1 for further details) allows you access to several key secondary resources under the heading ‘Evidenced based reviews’, which are described in Table 4.2.

It is a good idea to start your search in these databases since this will provide you with an excellent overview of the current literature.

4.1.2.2 Primary databases

Primary databases contain the references to original research published in the journals covered by each database. Each database will be accompanied with a definition of what areas it covers and which journals are included. The most well know medical database is probably Medline, which is a general medical database with the emphasis on North American journals. Other databases include:

Embase – Another general medical database, but with a greater number of European journals.

Embase – Another general medical database, but with a greater number of European journals. AMED – Allied and Complementary Medicine – this covers many journals of professions allied to medicine and complementary medicine.

AMED – Allied and Complementary Medicine – this covers many journals of professions allied to medicine and complementary medicine. Cinahl – This database includes nursing and therapy journals with a North American bias.

Cinahl – This database includes nursing and therapy journals with a North American bias. British Nursing Index – This is a smaller database for nursing but with British and European bias.

British Nursing Index – This is a smaller database for nursing but with British and European bias. Psycinfo – Contains psychology journals and allied fields.

Psycinfo – Contains psychology journals and allied fields.Each database has a slightly different content but there are vast areas of overlap between different databases. The most thorough search will include most of these databases but a more general overview of the literature can be obtained by searching two or three.

The databases are searched using search engines such as PubMed, Ovid, or Dialog Datastar. Each search engine enables searching of a specific selection of databases. The most well know is PubMed since it is freely available on the internet: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez. However, this only gives you access to Medline and for nursing, therapy and other allied professions it is usually important to search other databases.

Table 4.2 Details of the content and location of secondary databases.

| Secondary databases | Contents |

| Cochrane Library www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane | Provides high-quality, independent evidence to inform health care decision-making. It is often regarded as the gold standard for evidence. The Cochrane Library includes: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; Cochrane Reviews) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; Other Reviews) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Clinical Trials) Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR; Methods Studies) Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA; Technology Assessments) NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED; Economic Evaluations) A detailed description of each database is given on the Cochrane Library website (See ‘More about the Cochrane Library’ > ‘Product Descriptions’). |

| Bandolier www.ebandolier.com | Bandolier aims to find information about evidence of effectiveness (or lack of it), and put the results forward as simple bullet points of those things that worked and those that did not. Information comes from systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomised trials, and from high quality observational studies. |

| Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS) http://cks.library.nhs.uk | This is an NHS funded resource that provides access to practical and reliable clinical knowledge about the common conditions managed in primary and first contact care. It helps health care professionals confidently make evidence-based decisions about the health care of their patients and provides them with the know-how to safely put these decisions into action. |

| Research Findings electronic Register (ReFeR) www.refer.nhs.uk | This is a database of the findings of research studies funded by the Department of Health and results are published here before publication. Thus, ReFeR fills the gap in access to research findings between project completion and publication. |

For NHS staff the NLH provides access to Dialog Datastar which allows searching of all the databases listed above (see Section 4.3.1.3 for further details).

4.1.2.3 Which databases will give you the best answer?

Usually the first place to search would be the secondary databases for summaries of the primary research. If the information you are looking for is not there you need to choose the most appropriate primary database, which will depend on the topic you are searching. For a comprehensive search you should search several databases including both primary and secondary.

As you develop your literature searching skills you will become familiar with the content of each database and it will become easier and quicker to decide which databases to use. It is worth spending some time searching each database and exploring its content.

4.1.3 Devise a research strategy

You have your key search terms from your PICO analysis and have decided the most appropriate databases to search. There are two main ways to search databases: text word searching and using the thesaurus, and a comprehensive search will use both strategies. If you are doing a quick search to get an idea of what information is available, you may choose to use only one strategy.

4.1.3.1 Text word searching

Text word searching, as the name implies, searches the database directly for the word you type into the search box, and the search engine will retrieve documents containing that word or phrase.

Using text words, you are more likely to get unrelated articles and a larger but less specific retrieval. The search engine will only identify the exact word you type, so different spellings, misspellings and related words will not be picked up.

4.1.3.2 Thesaurus

In all the databases each entry is assigned a series of key terms that relate to the topics covered in the article. These have different names in different databases, for example; Medline calls them Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms), Embase uses EMTREE and AMED calls them descriptors. These terms comprise the thesaurus for each database. They are hierarchical with major broad terms at the top of a ‘tree’, which are then sub-divided into increasingly specific terms forming the ‘branches and twigs’ of the thesaurus tree.

When using a thesaurus search you retrieve articles which have the specific term assigned to them. This avoids the text word problems of different spellings or terminology and hence the search is likely to be more specific. However, since each database has a different thesaurus you will need to search each individually, possibly with slightly different thesaurus terms.

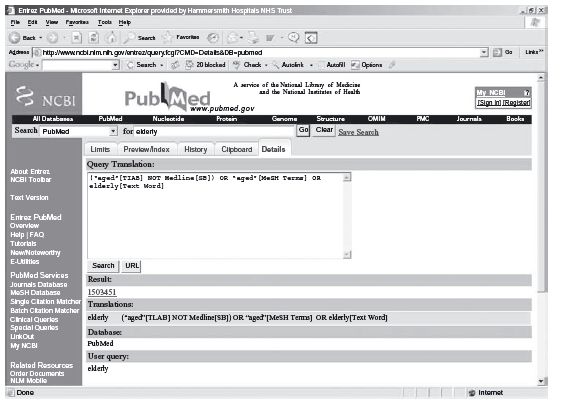

In order to search using thesaurus terms you first need to choose the correct term by searching the thesaurus. Each search engine achieves this in slightly different ways but as an example PubMed has a MeSH database link on the left hand side of the home page. From here you type in your key word and possible MeSH headings are displayed, and you check the one that most closely matches your key word. However, to make things really easy PubMed automatically maps any text word typed in on the main search page to the thesaurus (MeSH terms). You can check which term has been chosen by looking in the ‘Details’ tab. For example, a text word search for ‘elderly’ is automatically mapped to the MeSH term ‘aged’ in PubMed (see Figure 4.1).

4.1.4 Search sources effectively

To make searching more sensitive and specific there are various tools you can employ. These include:

Figure 4.1 Screen print of the ‘Details’ tab showing how PubMed has automatically searched for the text word and the MeSH term (www.pubmed.gov – a service of the US National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree