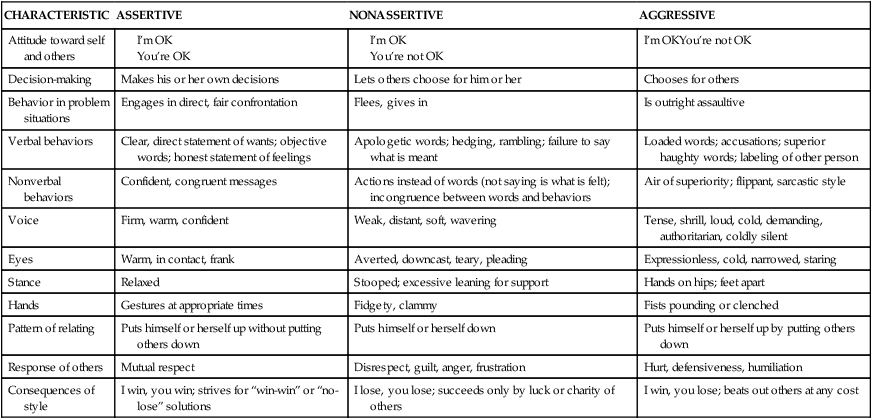

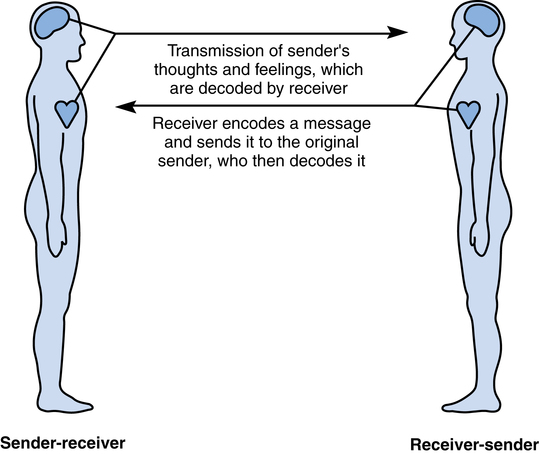

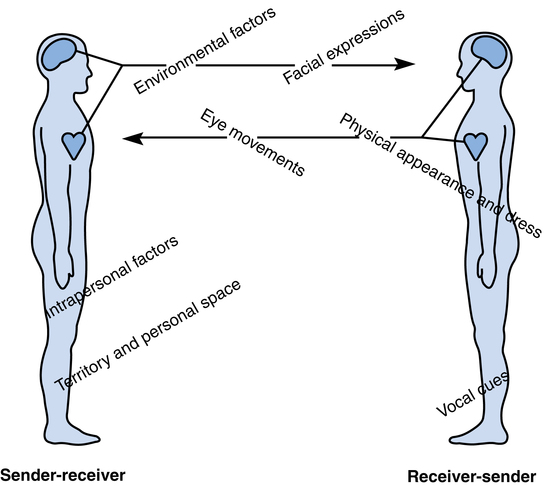

Chapter 1 1. Identify the functions of interpersonal communication in nursing 2. Distinguish between assertive, nonassertive, and aggressive communication 3. Identify a three-step process to build assertiveness skills 5. Identify irrational beliefs that impede assertive communication 6. Explain the DESC (describe, express, specify, consequences) script for developing an assertive response 7. Identify three types of assertions 8. Identify three essential criteria for presenting an assertive response 9. Describe the behavior of an assertive nurse 10. List the advantages of assertive communication 11. Describe responsible communication in nursing 12. Discuss the role of caring in nursing 13. Participate in exercises to build skills in responsible, assertive, caring communication This book is designed to help you improve your ability to communicate assertively and responsibly with your clients and colleagues and to demonstrate caring, what Kleen (2004) calls a professional core belief, as you explore and respond to the uniqueness of each individual (Wilson, 2008). Nursing students can make use of this book as they begin their professional journey. Practicing nurses will also find this work useful as they come to understand that clear communication is an essential ingredient for success in a rapidly changing healthcare climate. Communication with clients, colleagues, administrative officials, and staff members of other community agencies is essential as nurses’ roles change and more nurses move into the community to practice. If you have not read this book’s introduction, do so now, and remember this as an important practice when reading a text, to be able to read actively, seeking to explore the intention of the book, posing questions to yourself as you read to help you fit what you read into your own experience, to retain content, and to be an adult learner, growing your own skills for health caring. Communication involves the reciprocal process in which messages are sent and received between two or more people. This book focuses on the communication exchange among you, the nurse, and your clients and colleagues. Communication can either facilitate the development of a therapeutic relationship or create barriers (Stuart, 2009). In an interaction between two people (e.g., a nurse and a client), each person is both a sender and a receiver and alternates between these two roles. When senders are speaking, they are also receiving messages from the person who is listening. Listeners not only are receiving speakers’ messages but also are simultaneously sending messages. Figure 1-1 illustrates this reciprocal nature of the communication process. • Environmental factors: formality, warmth, privacy, familiarity, freedom or constraint, physical distance between people, climate, mood, architecture, arrangement of furniture • Territory and personal space: crowding, seating arrangements, roles, status, position, physical characteristics (size, height) • Physical appearance and dress: body shape, race, body smell, hair, gender, body movements, body adornments, posture, age • Nonverbal cues: facial expressions, eye movements, vocal cues • Intrapersonal factors: developmental stage, language mastery, differences in perception, differences in decision-making processes, differences in values, self-concept • The use of “I” messages to own one’s responses, such as, “I don’t agree with you,” instead of “you” messages, which sound blaming, such as, “You are wrong” Note that any of the preceding factors has the potential to facilitate communication or to act as a barrier to effective communication, depending on the situation. When these factors are considered, the interpersonal communication process looks something like the diagram shown in Figure 1-2. In your interpersonal relationships as a nurse, you will act as both sender and receiver. The purpose of this book is to help you develop your clarity as a sender and your comprehension as a receiver of messages. You will learn how to deliver assertive and responsible messages and to accurately decode messages from your clients and colleagues. You will be able to confidently interpret both direct and indirect requests and make responsible decisions about how to respond assertively (Box 1-1). The assertive nurse appears confident and comfortable. Assertive behavior, an active behavior, is contrasted with nonassertive or passive behavior, in which individuals disregard their own needs and rights, and aggressive behavior, in which individuals disregard the needs and rights of others. The assertive nurse is positive, caring, nonjudgmental, clear, and direct without threatening or attacking (Table 1-1). Table 1-1 Assertive and Nonassertive Styles of Communication Modified from Piaget G: Characterological lifechart of three fellows we all know. In Phelps S, Austin N: The assertive woman, San Luis Obispo, Calif, 1975, Impact Publishers; and Gerrard B, Boniface W, Love B: Interpersonal skills for health professionals, Reston, Va, 1980, Reston Publishing. Assertiveness is a matter of choice. It is important to feel confident that you can speak up for yourself, yet it is not necessary or even wise to speak your mind in every situation. With each person you encounter in any situation, you have the choice of communicating in an assertive or nonassertive style. The words you choose and the way you express them can be assertive, nonassertive, or aggressive. Realistically, you may not always have the energy or desire to assert your rights or express yourself fully. There are times when people cannot respond rationally, such as when they are experiencing high levels of anxiety or panic. A person might fear retaliation from a manager or fear the loss of a job. You must choose the issues for which your assertive behavior is appropriate as well as when, where, and with whom to express your assertiveness. The goal in this text is to help you develop the skills that will enable you to choose to act in the best interests of yourself and your clients. Remember, assertiveness helps you give or receive immediate feedback about a behavior that might have serious consequences if ignored (Grover, 2005). This “positive pushback” might be live saving (Gaddis, 2008).

Responsible, assertive, caring communication in nursing

The meaning of interpersonal communication

The meaning of assertive communication

CHARACTERISTIC

ASSERTIVE

NONASSERTIVE

AGGRESSIVE

Attitude toward self and others

I’m OKYou’re not OK

Decision-making

Makes his or her own decisions

Lets others choose for him or her

Chooses for others

Behavior in problem situations

Engages in direct, fair confrontation

Flees, gives in

Is outright assaultive

Verbal behaviors

Clear, direct statement of wants; objective words; honest statement of feelings

Apologetic words; hedging, rambling; failure to say what is meant

Loaded words; accusations; superior haughty words; labeling of other person

Nonverbal behaviors

Confident, congruent messages

Actions instead of words (not saying is what is felt); incongruence between words and behaviors

Air of superiority; flippant, sarcastic style

Voice

Firm, warm, confident

Weak, distant, soft, wavering

Tense, shrill, loud, cold, demanding, authoritarian, coldly silent

Eyes

Warm, in contact, frank

Averted, downcast, teary, pleading

Expressionless, cold, narrowed, staring

Stance

Relaxed

Stooped; excessive leaning for support

Hands on hips; feet apart

Hands

Gestures at appropriate times

Fidgety, clammy

Fists pounding or clenched

Pattern of relating

Puts himself or herself up without putting others down

Puts himself or herself down

Puts himself or herself up by putting others down

Response of others

Mutual respect

Disrespect, guilt, anger, frustration

Hurt, defensiveness, humiliation

Consequences of style

I win, you win; strives for “win-win” or “no-lose” solutions

I lose, you lose; succeeds only by luck or charity of others

I win, you lose; beats out others at any cost

Responsible, assertive, caring communication in nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Moments of Connection…

Moments of Connection…